How the USGA built a stadium from scratch to host the 2015 US Open

UNIVERSITY PLACE, Wash. — Think for a second about the word denuded. That’s the term that Tony Tipton, Pierce County (Wash.) parks and recreation director, uses to describe the former state of the land on which Chambers Bay Golf Course now sits, ready to host the 2015 U.S. Open.

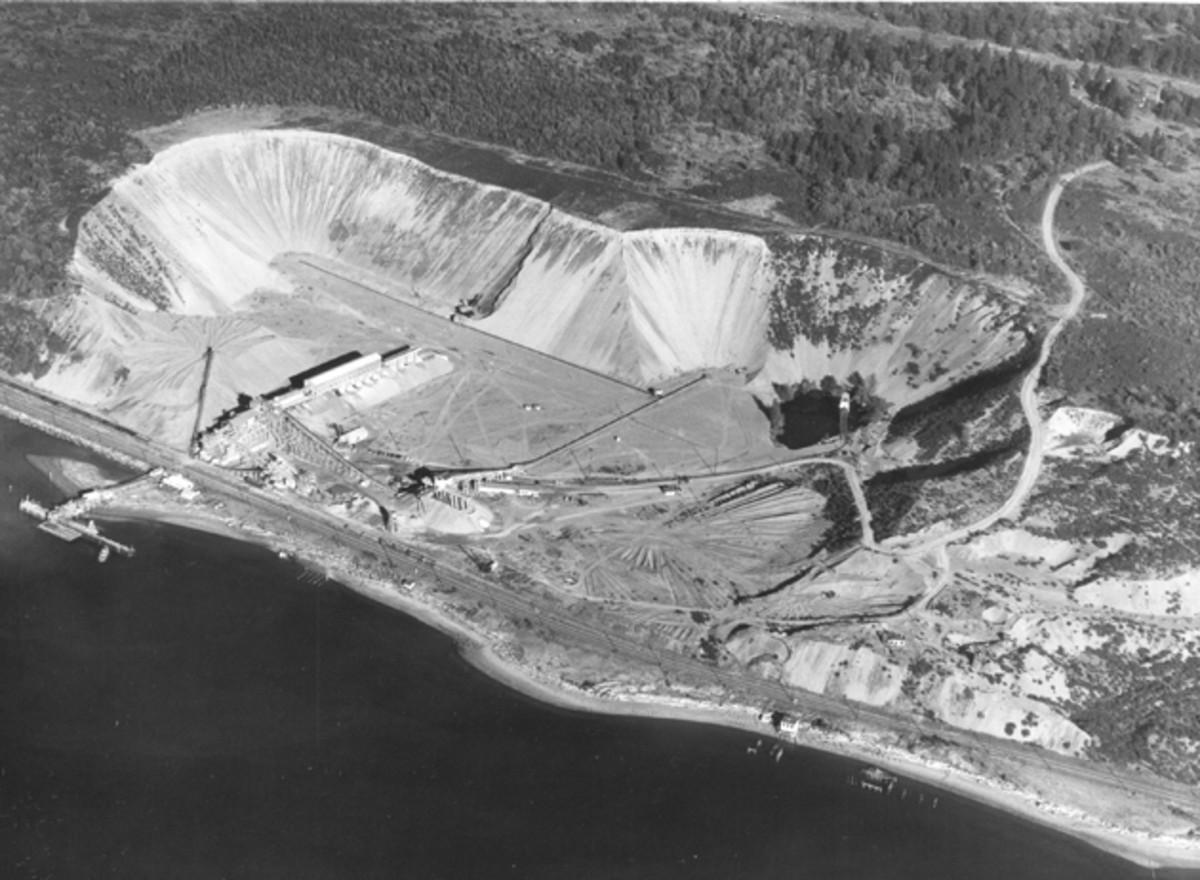

The site of a gravel-mining pit for more than a century, the 930-acre parcel of land along the Puget Sound not far from Tacoma was completely barren, scraped clean of form and life, when the county bought the site in 1992. Fifteen years later, Chambers Bay, a true links-style course designed by Robert Trent Jones II, opened for play. And roughly six months from now, it will present the first-ever U.S. Open Championship in the Pacific Northwest.

Having awarded Chambers Bay with the Open in 2008, the USGA now must essentially build a golf course stadium to welcome the 40,000 fans and volunteers who will descend each day of the tournament on the decidedly non-stadium site tucked between residential neighborhoods and picturesque Puget Sound vistas.

“There is a misconception that all this just pops up,” Danny Sink, director of the 2015 Open, tells Edge. “Ask anyone in arena management and ask them to do their job in an outdoor facility with no infrastructure.” Sink pointed to the difficulty of managing some 300 structures that get built on the site, everything from vendor tents to temporary lockers and player dining. He says that not having the infrastructure in place—Chambers Bay has no permanent clubhouse—allows the USGA to build as they want, something they prefer.

And with one of the biggest sporting events ever to hit the Pacific Northwest on tap, this stadium better fit the bill.

Chambers Bay already has some unique stadium-like features going for it. But it also faces some challenges. With the 18 championship holes tucked close to the water in a mined-out section of land and built into a hillside, a ridgeline spans two sides of the 7,585-yard course. During non-U.S. Open time, this ridge contributes to part of a 5-kilometer Grandview Trail that rises above the site and then dips down into it, circling right through the course—the only known public path through a golf course other than at St. Andrews in Scotland—before rising back to the ridge.

Designing the ultimate pro athlete recovery center — in the air

Sink will use this trail to help move spectators through the site. And expect to see folks doing some stopping here too. What other course has a vantage point from which you can see 12 holes in full view?

“We will see binoculars out here,” Sink says. “People will try to get on to that.”

This cartless course doesn’t boast a variety of walking paths. The USGA will use the public trail and a large maintenance path as the main spectator arteries. An easement just off the railroad tracks that wedge between the water and the course’s 16th and 17th holes will give planners a fourth major area through which spectators can move. And the active tracks—both for freight and passenger trains that travel on the main north-south rail connection between Portland and Seattle—will offer up some Safeco Field-like ambiance akin to Scottish links courses.

With some holes tough to access for those trying to following groups, Sink will bring in about 15,000 bleachers for the course and another 2,000 bleachers for the practice area. He plans to have bleachers on about 14 of the 18 greens.

The bulk of those bleachers will be situated at 18, originally designed as a championship-finishing hole. The green tucks into a stadium bowl, with the ridge above offering space for 6,000 bleachers in an L shape.

But still some will want to mosey around. Sink says there are plenty of places to do that.

Sole music: Inside Brooks Running's new HQ and research lab

People may park at 18, visit the merchandise tent just off the fairway and then go up behind the 14th tee on the Grandivew trail and watch players hit tee shots. “There are 20 different vistas like that,” Sink says. “If you want to watch someone on a green, turn the other way and watch four greens. It will be hard for people to decide [where to watch from].”

Along with the stadium-style seating at 18, expect a mini-stadium feel at 17, right along the water. Sink says the beauty of the variety of locations at this makeshift 225-acre stadium is that each vantage point offers views of different holes and the Puget Sound.

As Chambers Bay offers mini-stadium experiences inside the larger setting, with everything tucked into the 100-year mining operation, the ambient noise of Chambers Bay is like no other stadium. Sink says that, having dropped an entire golf event inside a carved-out bowl with nature and water on the open side, it will be interesting to see how the reverberating cheers flow across the course.

With only one tree on the course—the famed “lone fir” on hole 15—sound will carry. Will a roar on 18 impact play on 12? Will the passing trains create distraction or increase novelty?

“You can stand on the trail [up above] and hear guys on the green talking,” Sink says. “Sound is going to be huge here. From an audio standpoint, it will be a very interesting U.S. Open.”

It will be no CenturyLink Field, that is certain. But with no hard-and-fast concrete stadium structure, hosting more than just the 15,000 bleacher-seating fans requires careful planning.

The USGA has sold 30,000 tickets per day, but with volunteers, media and vendors the organization expects about 40,000 people on site each day, average for U.S. Opens. “We could sell 100,000 tickets, but we want people to have a good experience,” Sink says. “We don’t want you to not be able to move. We want you to be able to get on a shuttle bus and get here quickly and effectively and feel comfortable in a great spectator experience.”

Warriors flush toilet look, release new modern arena renderings

With a tight footprint inside the golf course, the majority of the infrastructure will occur outside the course. During the Open, the USGA will turn one of the course’s two ranges into a hospitality village, just mere steps from the course. Every stadium needs suites. Chambers Bay will get its suites alongside the 7th hole, adjacent to the hospitality village, complete with glass fronts.

The public park that sits south of the 18th fairway and the old concrete mining relics will turn into a fan zone and also serve as passage in and out of the course. Having the vast majority of concessions and public space outside the ropes, allows the focus inside the bowl to remain on the golf.

With limited parking in the residential area, all fans will leave their vehicles at a designated lot away from the course and shuttle to Chambers Bay—according to a plan that won’t be finalized until early 2015. Ideally, a paved eight-lane highway leads to the opening gates, Sink says, but that isn’t even remotely the case for Chambers Bay. Strategically placed parking lots—with the cooperation of the local community and law enforcement controlling about 35 major intersections near the course to allow for shuttle buses to remain on schedule—will help the roughly 300 shuttles to stay in a constant rotation.

- MORE EDGE: Living life on the slopes with Louie Vito

The USGA and Pierce County plan up to three large parking lots for the general public and another dozen smaller lots for players, vendors and media.

With planning well underway, by the time next June rolls around, what now looks like a picturesque neighborhood golf course will morph into a weeklong stadium experience. With nothing denuded.

Tim Newcomb covers stadiums, design and gear for Sports Illustrated. Follow him on Twitter at @tdnewcomb.