Athletes can now track hemoglobin and pulse rate levels without getting bloodwork

The long quest for a place at next year’s Ironman world championships has already begun, even before this season’s event has taken place in Kona, Hawaii, on Oct. 8. That journey will be a strategic fight for ranking points, finishing as highly as possible in the races you compete in so that you qualify for the season finale, while trying to race as little as possible and save your energy so that you can contend for the world title.

Triathlete Jarrod Shoemaker is only just stepping up to Ironman-distance events, but has more than a decade’s worth of experience training for and racing triathlons, including representing the U.S. at the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games.

“For me it’s always been about trying to figure things out about what’s going on with my body because you really don’t know,” he says. “You feel good or you feel bad.”

At college back in the early 2000s, Shoemaker had wanted to study biology, but required classes and labs for that major had clashed with his commitment to Dartmouth’s track and cross-country teams, so he took history instead. As a pro athlete he has sought out ways to use science and technology to his advantage. “There are so many tools available right now, he says. “It’s really finding the tools that mean something and that actually make sense.”

One of those latest tools is an iPhone-sized device called Ember that can measure the concentration of hemoglobin in an athlete’s blood. Hemoglobin is the protein in red blood cells that binds to oxygen, allowing those cells to transport it around the body. Each red blood cell carries about 270 million hemoglobin molecules, and each one of those can carry four oxygen molecules. The concentration of red blood cells, known as an athlete’s hematocrit, is something endurance athletes can obsess about. Because oxygen is required for muscles to generate power aerobically, hematocrit determines the oxygen carrying capacity and effectively puts an upper limit on an athlete’s endurance exercise ability.

Attempting to increase hematocrit is why some athletes train at high altitude, while others sleep in hypoxic tents. Over time, a person’s body will respond to low oxygen conditions by producing more red blood cells in order to try to capture more of the ambient oxygen. Boosting red blood cell concentration is also why athletes can turn to performance-enhancing drugs, such as synthetic erythropoietin (EPO), which stimulates red blood cell production.

Figuring out fatigue: A tired brain can hinder performance as much as a tired muscle

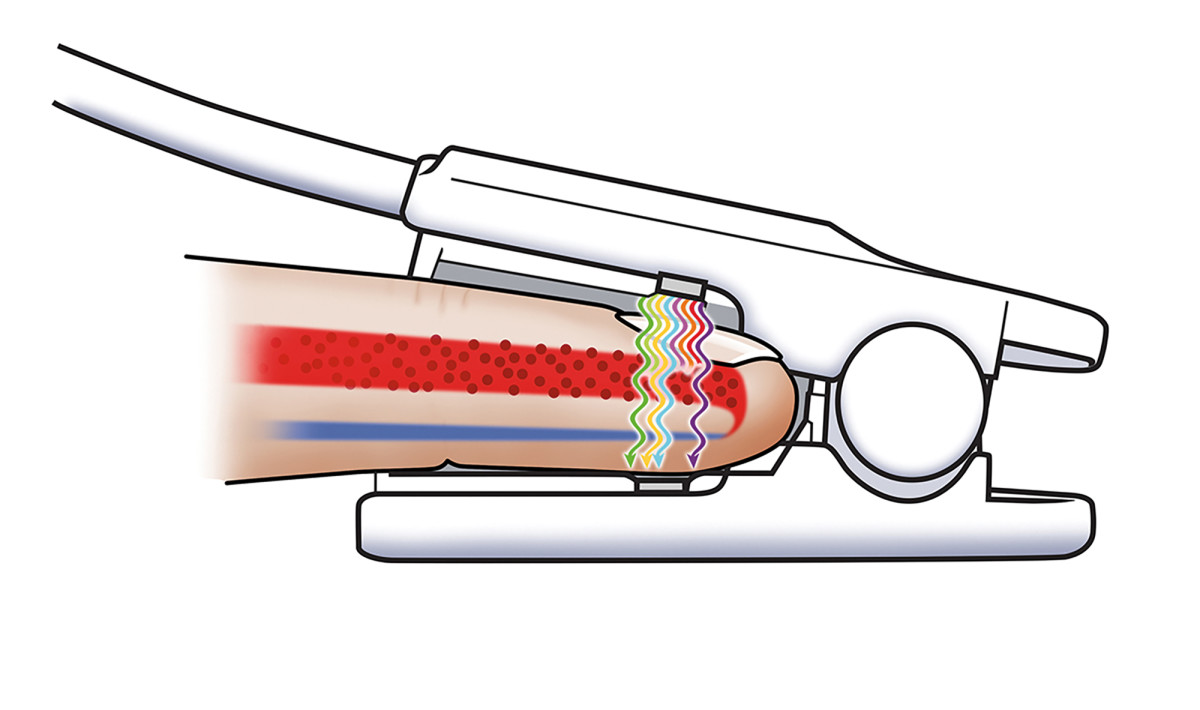

Similar to pulse oximeters used in hospitals, Ember has a finger clip sensor connected to the main device by a wire. This clip shines different wavelengths of light through a person’s fingertip, and measures how much of each wavelength gets absorbed by tissue, bone, and blood. Each time a person’s heart beats there is a surge in the flow of the blood through the arteries, and this affects how much of the light from the clip passes through their finger. By looking for that pulse-related change in the light signal, pulse oximeters can both measure heart rate and determine characteristics about the blood. For example, Hemoglobin changes color according to whether it is carrying oxygen or not—bright red when it is, and dark red when it is not—and so measuring how much of each color gets absorbed can allow pulse oximeters to determine blood oxygen saturation.

Cercacor, the company that makes Ember, has already released a basic version of their hemoglobin-measuring device ($399) but is hoping to bring out a premium model that will capture additional measurements later this year ($699). Once a person has bought the device, and connected it up to their smartphone, it is used on a pay-per-view-like model: simple pulse readings are free, but hemoglobin-related measurements will cost 99 cents each, after using the 200 preloaded measurements on the device.

Next year users will also be able to buy a software upgrade ($200) that will allow them to measure some additional parameters, including how much of their oxygen carrying capacity may have been compromised by carbon monoxide poisoning. (Carbon monoxide from smoke binds to hemoglobin, preventing the molecule from carrying oxygen, and turning it a cherry red color.)

Before using Ember, Shoemaker, 34, would have his hematocrit taken by blood test by his doctor a couple of times each year. But he says the results, “didn’t influence much of my training because I saw them more as static numbers.”

“I always thought that your hemoglobin is what it is and it doesn’t change that much except when you go to altitude, and then it goes up,” Shoemaker says. But with Ember, Shoemaker tracks his hematocrit on a far more frequent basis: every morning and every night, as well as before and after harder workouts.

“If you take frequent measurements you start to build a rich data set specifically for you,” says Greg Olsen, director of industrial design and user experience at Cercacor.

When Shoemaker heads up from his home base of Clermont, Fla., (300 feet above sea level) to train in Boulder, Colo., (5,400 feet), Ember gives him day-by-day feedback on how his body is adapting to the elevation.

Best running and workout accessories for your new iPhone 7 and iPhone 7 plus

“Within the first few days you’re at altitude most people will get a spike and a drop,” says Abe Kiani, an anesthesiologist and Cercacor’s VP of medical affairs. However, that “has nothing to do with the actual amount of hemoglobin changing, it’s a fluid shift that is induced by the elevation change,” Kiani says.

The key to boosting red blood cell counts is long-term exposure to low oxygen environments. “Your kidneys have to see the hypoxia,” Kiani says. “Your kidneys need to see that to release the hormone erythropoietin that acts on the bone marrow. It’s a whole process that needs to go. Doing one day won’t do it.”

Shoemaker started using Ember in April 2015, and he has learned that within 1-2 weeks up in Boulder he will start to see a rise in his hemoglobin from his sea-level number of 14.5 grams per deciliter up towards 16 grams about two months later. After that the concentration will plateau, so training longer at altitude may not be effective for him. When he returns to sea level, he will hold onto that higher hemoglobin concentration for 2-3 weeks before it begins to drop back significantly, making that period the ideal time for racing.

This year Shoemaker hopes to use that information to maximize his training numbers, peak for his races, and collect enough ranking points to ensure he is on his way to Hawaii by October 2017.