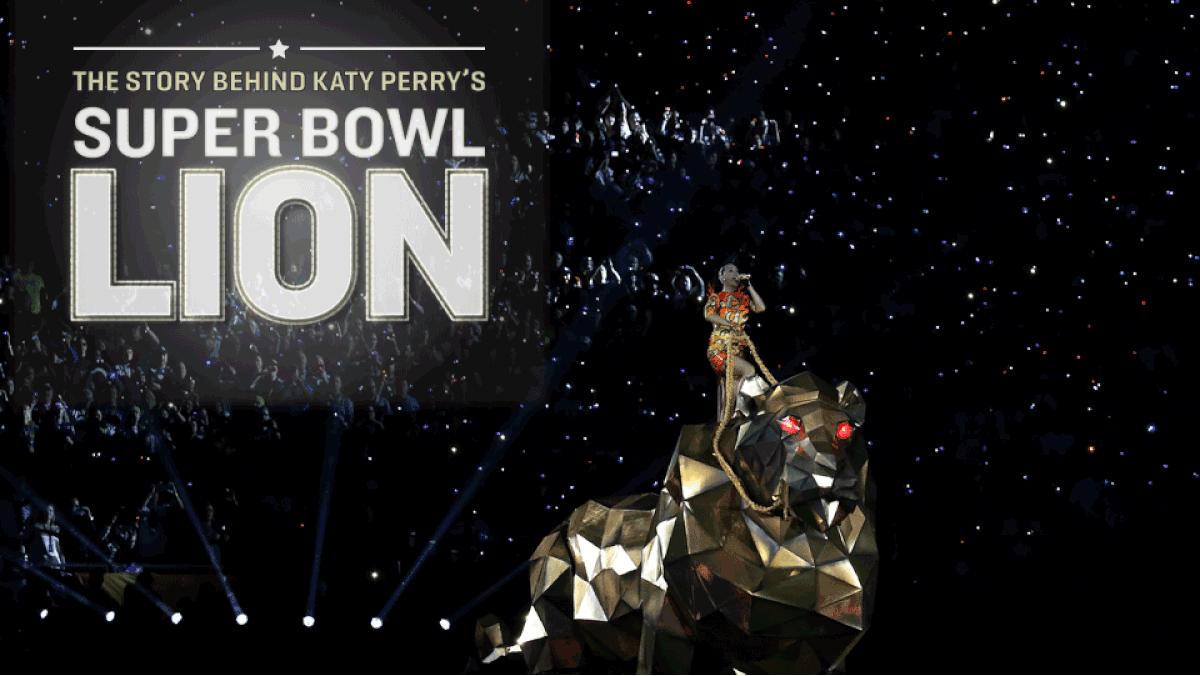

The story behind Katy Perry's Super Bowl halftime show lion

Baz Halpin couldn’t care less about the game.

Halpin, Katy Perry’s creative partner for the last five years, was watching the opening quarters of Super Bowl XLIX in February from a control truck outside University of Phoenix Stadium, and his mind was elsewhere.

Early in the fall of 2014, the NFL had reached out to Halpin and Perry about performing in the middle of America’s premier sporting event. Saying yes was the easy part. Hashing out a creative concept for one of the biggest stages on earth was another. For Halpin, show time was drawing near.

The earliest ideas had centered on a giant opener—literally. Halpin and Perry wanted to start the show with her riding a lion. As things turned out, that lion—26 feet long, 16 feet high, weighing nearly 1,600 pounds—would be a fully operational puppet crafted by Michael Curry Design, the team responsible for the props used in The Lion King show on Broadway. If all went well, it would be kept a secret until halftime.

As Halpin waited nervously as the first half between the Patriots and Seahawks flew by, he suddenly realized that months of planning, months of production, weeks of rehearsals and commitments to secrecy were about to be ruined by the one thing he hadn't considered for a second -- daylight.

The game had started shortly after 4:30 p.m. in Arizona. As it moved closer and closer to halftime, the sun was still shining brightly, and brightness would completely change the look of the lion’s reflective shell, and just about every visual scene would look vastly different bathed in sunlight.

*****

Michael Curry must love his job.

He is the Willy Wonka of real-life, giant toys. The pieces his company has made for The Lion King, one of the longest-running Broadway shows, are an integral part of the musical’s success.

Curry had also worked with the NFL and Perry in the past, making him the logical choice when Halpin and Perry decided last fall about their opener. It had to be big, it had to be beautiful and it had to stun the audience.

Curry’s company started construction of the lion in mid-November in Scappoose, Ore., a town of fewer than 7,000 people near the northwestern tip of the state. Perry was interested in a stylization of Origami, a folded, edged look as opposed to perfectly lifelike, giving Curry the idea of constructing an exterior of 1,000 fractured panels.

Once the look was finalized, production began. Designers used computers to create models of a lion that would be properly weighted to move in a lifelike manner. In Curry’s Scappoose warehouse, robot arms were used to carve a to-scale foam replica of the lion in order to properly fit the panels.

The spine of the lion was made of a “tubular aluminum subframe.” The rest of the piece was held together by carbon fiber. On the outside, the reflective panels were made of a paper-thin, polycarbonate that was painted gold. The aluminum, carbon fiber and polycarbonate were used to keep the lion lightweight and movable.

The lion was constructed with 18 pivots, allowing it to move its head, neck, shoulders and legs. Due to the lion's size, Curry settled on having it move at a pace three times slower than in real life, making it look even weightier and more commanding.

Production ended soon after the first week of January. From there, the lion made a 23-hour, 900-mile bus trip from Oregon to Los Angeles. The piece remained largely whole and was loaded onto a flatbed truck that enclosed the lion in a canvas tent. The drivers had to sign non-disclosure agreements to ensure no one would find out about the work of art before the show.

After around 3,500 labor hours, the lion was finally on its way.

*****

Rehearsals began in earnest in Los Angeles about three weeks before the Super Bowl. Renting out an empty arena, Perry and a team of puppeteers rehearsed their movements more than 40 times over two weeks.

The lion then took another bus ride, this one six hours, to Arizona for a week of rehearsals on the actual field. By show day, the team had gone through four full runs of the halftime show.

The lion was stored in a compound of tents about 300 yards away from the stadium. As it was moved back and forth to rehearsals, it remained hidden under a black cover.

Show-day prep started at about 9:30 in the morning, six hours before the game.

Shortly after the first quarter, the lion was wheeled from the compound over to the stadium. With about two minutes left in the first half, the lion would be moved 10 feet from the field, on a ramp behind the Seahawks end zone. But first things first.

*****

With five minutes left in the second quarter, the Patriots and Seahawks had combined for only one score, an 11-yard touchdown catch by Brandon LaFell. The game was moving at a fast pace.

Halpin was in the control truck, bemoaning that at no point had he considered the sun becoming a factor. Then, the improbable happened.

The Seahawks tied the game at seven with an eight-play, 70-yard drive capped by a Marshawn Lynch touchdown run. The Patriots countered with their own eight-play touchdown drive, which took the game clock to 31 seconds left in the half.

Halpin was still nervous. The sun hadn’t gone down yet, and Seattle could take a knee and send the game into halftime.

Fortunately for him, Seahawks coach Pete Carroll kept his offense on the field and attempted to score. In a drive that resulted in an 11-yard touchdown catch by Chris Matthews, three timeouts were called as well as a stoppage in play for a penalty.

As the game reached halftime, the sun had finally gone down.

“We made darkness by something like 25 seconds,” Halpin said. “For months and months, I never panicked. Then the game was so fast—how did we not think about the sun? It was a miracle.”

*****

The lion started on a ramp behind the Seahawks end zone, still concealed by its black cover. The crew had six minutes to move it across the field to the goal line of the Patriots end zone, where it would start the show.

Once the lion was in position, the cover was removed. With 90 seconds until the show, the crowd got its first glimpse of the lion.

“Immediately, you hear the crowd,” said Jarred Kersley, who controlled the lion’s head. “It was a crazy mash of noise.”

Thirty seconds later, Perry made her way to the top of the lion using a rolling staircase. As Halpin watched from the truck, his star partner took control and started the performance with her appropriately-titled hit Roar.

“On the day of the show, I still get nervous,” Halpin said. “Katy was just so chill. She has absolutely no nerves.”

The lion moved slowly across the goal line toward the 40-yard line, moving its head up and down, looking left and right towards the crowd and roaring along to the music.

It took 11 people to work the puppet, a mix of performers and Curry employees. Kersley controlled the head’s movements using tech lines attached to each of his wrists.

Although Kersley was responsible for the face of a 1,600-pound piece of art, the physical part came easy. (He said that with enough training, most people with average strength could control the lion.) The mental aspect of performing in front of an enormous television audience was the daunting part.

The lion was only a small part of the overall show. After less than a minute and 40 seconds, Perry was due for a song change.

She slid off the lion using a 20-feet high, 2-feet wide pole that came down to a platform. After eight seconds, Perry began singing Dark Horse, and the lion was moved back toward the Patriots end zone.

*****

No one wanted to talk about how much the lion cost—not the NFL, not Curry and not Halpin—although Halpin did note, with a chuckle, that the price was “very reasonable.”

For now, if you want to see a similar piece you’ll have to check out Curry’s designs in The Lion King.

Halpin’s kept busy since the end of the show, with a whirlwind work schedule that’s taken him from Arizona to Los Angeles to New York to Las Vegas, before he heads back to California. Perry has remained busy, and she delivered another memorable performance at the Grammy Awards just a week after the Super Bowl.

The lion left the show with Perry, who probably won’t be able to use it as a tour piece but is keeping it safely stored in California. Unfortunately, it is too big to bring into her home.

Curry, who had to part ways with the lion, had one request of the pop star:

“I hope she’s feeding it well.”