If There Were Asterisks on Majors, They'd Have Been a Thing Long Before LIV Golf

In 1961, Roger Maris was on his way to a 61-home-run season for the New York Yankees when then-commissioner Ford C. Frick ruled that to break the record of 60 home runs in a season set by Babe Ruth in 1927, Maris would have to do it in 154 games versus the 162 games of the current season.

Frick suggested that a “distinctive mark” be created in the record book, which ultimately never happened because records were not controlled by Major League Baseball until years later.

So, the first major asterisk controversy died out.

Now, roughly 62 years later, Frick’s idea has emerged again in a different sport.

And this idea is just as asinine.

Instead of using a “distinctive mark,” this week’s word is “asterisks” or shift-8 on your keyboard.

The author of the newest silly comment is Talor Gooch, a full-time LIV golfer with a chip on his shoulder.

It’s a chip that has grown larger and larger as his success on LIV has continued, which includes three wins, player-of-the-year honors in 2023 and $50 million in two-plus seasons.

In the Cambridge Dictionary, one of the definitions of the word asterisks is, “something that makes an achievement less impressive or less complete.”

Winning at any level of professional golf is extremely hard, and to suggest that Rory McIlroy winning the Masters with a field of 80 or 90 without Gooch or other LIV golfers lessens the achievement requires a dig into golf history.

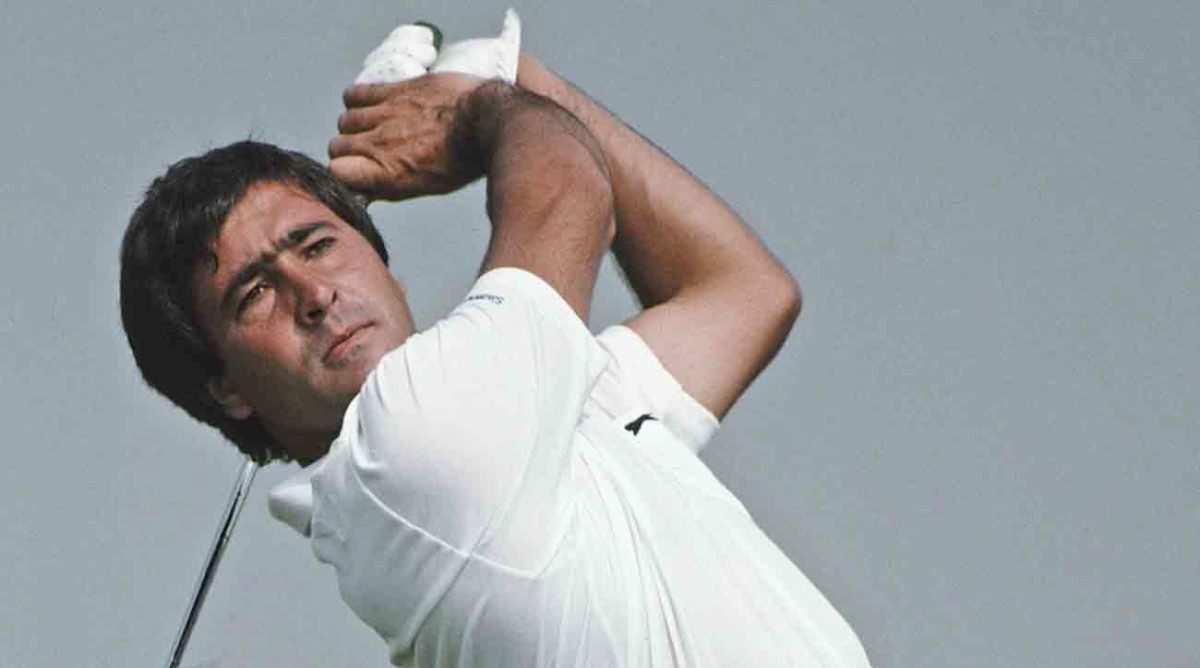

How about asterisks for majors that didn't include Seve Ballesteros?

The Hall of Famer played in 87 major championships, but he should have been in so many more.

In 1976, Ballesteros finished T2 in the British Open with Jack Nicklaus and Raymond Floyd, six shots behind Johnny Miller.

Floyd, Miller and Nicklaus then played all four majors in 1977, but Ballesteros was not invited to either the U.S. Open or PGA Championship.

Ballesteros was invited to the U.S. Open in 1978, but it took two major wins at the 1979 British Open and 1980 Masters before Ballesteros teed it up in the PGA Championship in 1981.

Many players on the European Tour suffered the same fate as Ballesteros, but none were as well-known as the swashbuckling Spaniard.

South African Bobby Locke suffered a similar fate as Ballesteros, teeing it up in his first major in 1936 at the British Open. Arguably the best putter of his era, Locke played in only one PGA Championship in 1947 and four Masters, the last in 1952.

Yet, Locke would win four Open Championships, two coming in 1952 and 1957, both after that last Masters appearance.

So, do the winners of majors when Ballesteros and Locke were sidelined deserve asterisks by their accomplishments?

Many believed when IMG founder Mark McCormack started the Sony Rankings in 1986—specifically to determine who should and should not be invited to majors—that situations like Ballesteros's and Locke's, to name just two that were slighted, would not occur again.

That first ranking on April 6, 1986, had a top three of Bernhard Langer, Ballesteros and Sandy Lyle, all players that had been snubbed by the majors at times during their careers.

Further down the list at 23rd was Sam Torrance and next to him at 24th was Nick Faldo.

In 1986, Torrance played in one major, the Open Championship, even though he was in the top 30 in the world at the beginning of Masters week.

Jack Nicklaus was ranked 33rd in the first ranking. Should Nicklaus’s sixth Masters victory and 18th major title have an asterisk because Torrance was not in the field?

Gooch has a legitimate gripe in that his jumping from the PGA Tour to LIV should not be a reason to keep him out of major championships.

Yes, it’s hard to gauge how good LIV players are now that they have gone to what many consider a less-competitive tour, but the leaderboard at last year’s Masters should have had doubters take note. LIV golfers Brooks Koepka and Phil Mickelson tied for second and Patrick Reed tied for fourth.

When Koepka won his fifth major at the PGA Championship, one would have hoped that would close the book on LIV questions, but instead the dilemma persists until the majors take a more responsible step toward opening their fields to the best players available.

Professional sports should never use an asterisk, but that doesn't mean the marks will remain out of the conversation.