Brave Hearts

The two teenagers sit transfixed in front of a television in a Mexico hotel room, where they are playing in an international tournament. The Atlanta Braves -- America's Team! -- are playing. This is the first major league game that either boy has ever seen. Thirteen-year-old Brayan Peña, the older of the two by 10 months, follows the action, but he is drawn to something else. He has always been más chubby than the other boys and never had a proper-fitting uniform. He is mesmerized by the crisp home whites of the Braves, the way the red logo pops off the jerseys. "Let's grow up to be Braves," he tells his best friend. "Yeah," says Yunel Escobar, "let's be Braves."

They shared everything growing up. Gloves, bats, balls, cleats, dreams, favorite teams -- Atlanta Braves, baby! -- even the same Buena Vista neighborhood of Havana. But here is something they did not share: a small fishing boat, with sharks and six-foot waves snapping at its sides as it washed across the Florida Straits in the first week of October in 2004. Escobar, who would turn 22 in another month, and at least two dozen others were crammed into the rickety vessel. His best friend, however, had already reached freedom. Five years earlier. In the backseat of a Mercedes. Without him.

Peña had wanted to tell Escobar about the plan he had helped hatch back in the spring of 1999. That April the two boys were members of the Cuban 17-and-under national team that would play for the Junior Pan-Am championship in Caracas. Brayan was the starting catcher, Yunel the starting shortstop. After a sleepless night a bleary-eyed Brayan was waiting in the hotel restaurant on the morning of the championship game when Yunel and the rest of his teammates arrived for breakfast. When Yunel asked about the bags beneath Brayan's usually bright eyes, Brayan said only, "Nerves. For the championship, of course."

Numerous agents had descended on Caracas for the tournament, including the gentleman who, according to Brayan, had e-mailed him three days earlier. The agent had told Brayan to look for a man in a white hat and white shirt in the hotel on the morning of April 15 if he wanted to defect. And don't, the e-mail warned him, tell a soul. As if Brayan needed the reminder. He knew what happened to those whom the defectors left behind. The lie-detector tests, the jail cells, the constant surveillance. After breakfast Brayan persuaded one of the five guards assigned to watch the team to let him go to the bathroom by himself. Instead he went to an elevator, pushed the button for the lobby and kept repeating, "White shirt, white hat. White shirt, white hat." When the doors opened, Brayan stopped for a moment, confused by the sight of a man in one corner of the lobby wearing a white shirt and another on the other side wearing a white hat. Then a man wearing both waved his arms and steered Brayan into the backseat of the black Mercedes. Brayan knew that Yunel would feel betrayed. But in this case, betraying his friend, he knew, was the best way to protect him.

Still, Brayan's defection would have consequences for Yunel. Cuban authorities did not believe that two boys who spent every weekend together -- Brayan pitching the first game of a doubleheader for the Mariano team, with Yunel as his catcher, then flipping positions and gear with his friend for the nightcap and following it up with a heaping scoop of Coppelia ice cream -- would not have shared such a secret. As it turned out, Yunel lost his best friend and gained the company of security guards who seemingly shadowed him everywhere for two straight years. "I couldn't even go to the bathroom by myself," he says now. Frustrated, Yunel would turn on his guard in the street and yell, "NO. ME. VOY. No me sigas más!" (I'm. Not. Going. Stop following me!) There would be no more international tournaments for Yunel, no luxury car waiting to whisk him away to freedom. A boat, two days adrift at sea, would be his only opportunity to leave.

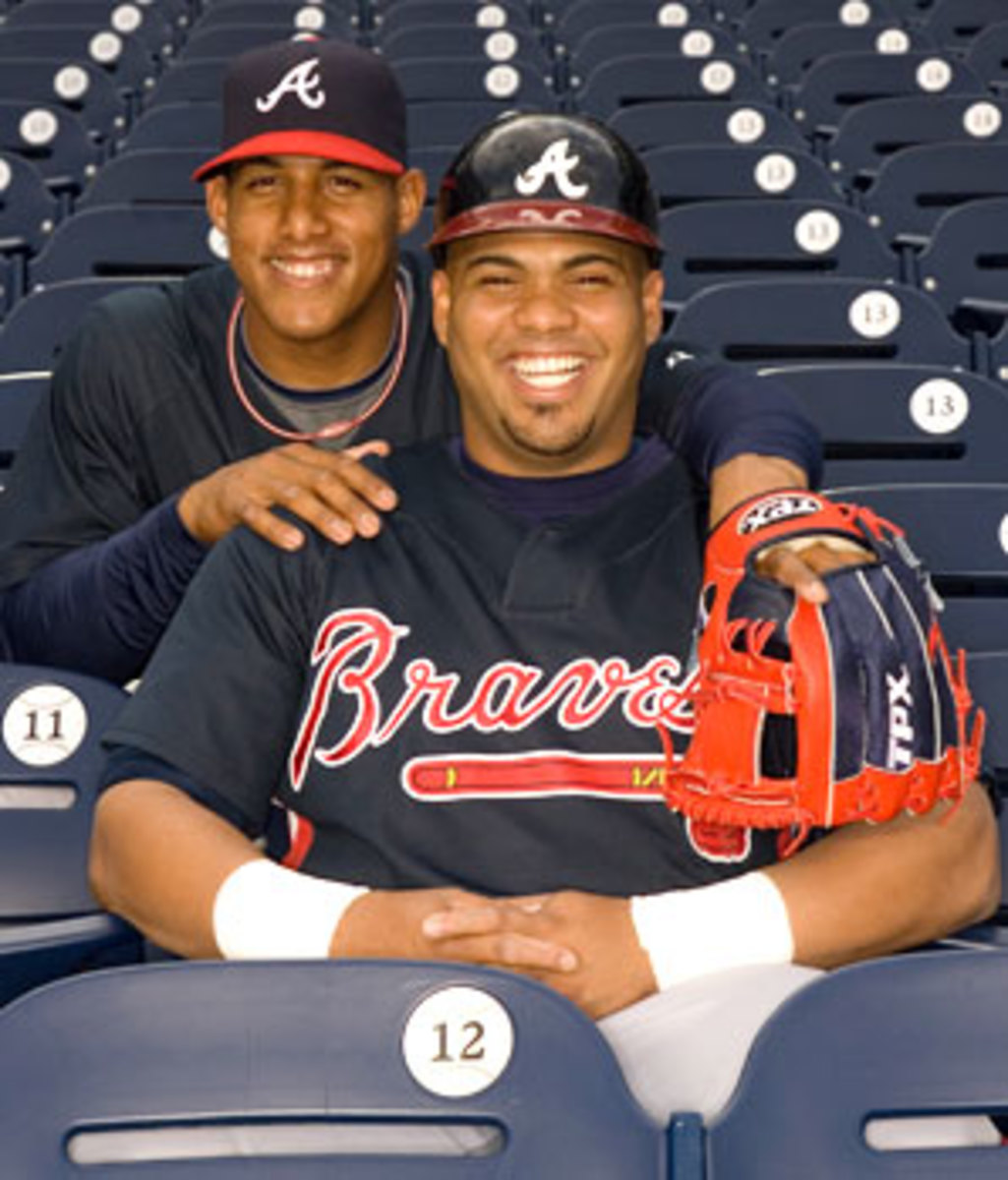

Destiny is the only explanation anyone in the Escobar or Peña clan offers for how two young men, best friends who grew up one street apart in Havana, could find themselves here, standing on the third base line of Nationals Park in the capital of the free world. As boys, Yunel Escobar and Brayan Peña had proudly worn and swapped John Smoltz and Tom Glavine jerseys that a family friend had smuggled into Cuba. On this March night, the first of the 2008 major league season, they wore the same crisp Braves uniforms that had so mesmerized them as boys. Escobar, a budding star, was the starting shortstop and second batter, Peña a backup catcher to two-time All-Star Brian McCann. "If you wrote our story," Peña says, "no one would believe it."

After Escobar's boat finally washed up in Miami in October 2004, he tracked down Peña's mother, Carmen Puente, who had managed to leave Cuba in 2002 and had settled in Miami. Peña was playing winter ball in the Dominican Republic. When he returned to Miami in January 2005, five years of separation dissolved in one embrace. The two young men spent that first evening together at a Cuban restaurant, where after a series of "You go first! No, you go first!" they filled in the giant gaps in their lives.

Escobar started by updating Peña about Peña's extended family still in Cuba. Then he spoke of his two days at sea, where he barely spoke, not even to his five teammates from the Havana club Industriales, Cuba's version of the Yankees, for fear of agitating other fellow passengers who were beset by dehydration, hunger and sickness. "Someone might just throw you off the boat if they didn't like you," Escobar said. He told Peña about the numerous suspensions from baseball that finally persuaded him to leave. He told how once, out of frustration, he'd thrown a ball at a fan, which led to one suspension. How he'd been suspended on another occasion for not wearing the right pair of black pants. How he'd been benched by coaches who questioned his loyalty to Fidel Castro. And, most important to Escobar, how proud he had been when he read in a newspaper that his más chubby friend had fulfilled his childhood dream -- their childhood dream -- and signed a contract with the Atlanta Braves.

Peña reciprocated with stories from rookie ball in the Appalachian League, where he hit .370 for Danville to win the batting title in 2001. The climb after that had been slower: two seasons in high Class A before being promoted to Double A in '04. He told Escobar how much he had missed him, missed that ear-piercing whistle that got a rise out of almost every opponent they'd played as juniors.

A month later Peña was back in spring training with the Braves while Escobar remained behind in Miami to audition for major league scouts. The Braves took Escobar in the second round of the 2005 draft, 75th overall. "We saw him as a premium talent," says Roy Clark, Atlanta's scouting director. "A lot of clubs didn't feel that they had enough background [on him]." Escobar's tense relationship with Cuban authorities in the aftermath of Peña's defection had limited his exposure to major league scouts. With little more than a few off-season workouts to draw upon, most teams were reluctant to take a chance on Escobar. The Braves, however, had an inside source: Peña, who was called up to the majors just days before the '05 draft. Clark peppered the young catcher with questions about everything from Escobar's skill set to his command of English to his family background. "The best recommendation we got was from Brayan," Clark says.

Escobar received a $475,000 signing bonus ($775,000 less than his best friend had been given five years earlier) and moved quickly through Atlanta's farm system, showing good plate discipline and a flashy, if erratic, glove. Last June 2, two years after he was drafted, he made his big league debut. He went 2 for 4 with a game-winning double against the Chicago Cubs and hasn't stopped hitting since. He batted .326 in 319 at bats last season, alternating among shortstop, third base and second base. During the off-season he lived in Miami, answering ? 7 a.m. wake-up calls from Edgar Renteria ("¿Estás ready?" Renteria would ask), who put his apprentice through all-day workouts even after Renteria was traded to the Detroit Tigers in November -- a move, ironically, that was forced by the rapid development of Escobar, who is seven years younger than the Colombian shortstop.

Having packed 12 pounds of muscle onto his 6' 2'' frame, Escobar has gotten off to another quick start in 2008, hitting .324 with a .529 slugging percentage in the season's first three weeks. Braves bench coach Chino Cadahia, a fellow Cuban who is close to Escobar, says, "He plays with . . ." and pauses before adding "ánimo," or soul. McCann compares Escobar with the Marlins' Hanley Ramirez. This is hyperbole, of course, but at the very least Escobar has earned entrée into the National League East's club of elite shortstops, which also includes the Mets' Jose Reyes and last year's National League MVP, the Phillies' Jimmy Rollins.

As for Peña, well, destiny has a sense of humor, doesn't it? While Escobar's career races forward like, say, a black Mercedes, Peña's better resembles a fishing boat adrift. Peña is blocked by McCann, who is two years younger than his backup. Despite a .314 career average in seven minor league seasons and an MVP award in the 2007-08 Dominican winter league, Peña has never batted more than 41 times in any of four big league seasons. "I don't have any doubt in my mind that Brayan Peña is a major league catcher," says Cadahia, a former backstop himself. "He needs the opportunity to prove that he can play at this level."

"Not too many people have the opportunity to play with their childhood best friend," Peña says. "Every moment I go to the field with him, it feels like we've been together forever. I am happy for his accomplishments."

What, Escobar is asked, has he liked most about his new country? "The sacrifices you make for your family always bear fruit," he replies. That's also how he explains why he does not worry about Peña's future. Someday the sacrifices that Peña has been making on Escobar's behalf since they were children will reward him as much as they have his best friend. Peña was the big brother who forced Escobar to do his homework so that his teachers in Cuba would let him play ball. Now he is the mentor who has introduced Escobar to MySpace and hi5 chats and texting on his cellphone.

The best friends talk about opening a restaurant together someday, though neither knows how to cook. "But children," Escobar says, "they're my life. I like to work with them." Along with Juan Pablo Echevarría, a Miami trainer, Escobar helps run a baseball academy for children ages eight through 12 when he returns to South Florida in the winter. They have a team: the Braves, of course. The children wear their pullover jerseys with pride and it is not hard to imagine one of the youngsters telling his best friend, "Let's grow up to be Braves."