The Passion of Roger Angell: The best baseball writer in America is also a fan

This story appeared in the July 21, 2014 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe to the magazine, click here.

Consider the writer. Stooped, thought-burdened, wrinkled, he wears his press pass on a lanyard around his neck like a yoke as he moves slowly to his workplace. Into the hollow of the X‑ray machine he pushes his small canvas bag, the one with the notebook that catches ink as surely as an ice dancer does his partner, and then he walks through the metal detector. There is a problem. The Yankee Stadium security guard, his countenance grim with boredom, asks the writer to flip over his pass so that he can reconcile the picture with the face. They do not match. The face photographed decades ago is full and fleshy. The writer’s face has grown as lean and angular as one painted by Giotto. The guard, still bored, waves him on. The writer laughs, not at the guard but at his old self.

Writing well is hard. It requires constant thinking. The gears, flywheels and levers of the mind click and clatter nonstop. Writing is flying an airplane without instruments, almost always through the dark storms of doubt. It is new every time.

There’s an added difficulty with writing about baseball: The writer ages but the players do not. They are perpetually young, replaced almost imperceptibly by younger versions of themselves. Every season is like a summer-stock version of Bye Bye Birdie. Then one day a ballplayer with $100 million banked calls you “sir,” and you realize the chasm has grown Olduvai Gorge–wide.

Over the last half-century nobody has written baseball better than Roger Angell of The New Yorker. What he does with words, even today at 93, is what Mays did in centerfield and what Koufax did on the mound. His superior elegance and skill are obvious even to the untrained eye.

Did I say Mays? Suddenly Angell leaves the colossal mallpark in the Bronx for the Polo Grounds of upper Manhattan. It’s Aug. 15, 1951. The long, late afternoon shadows of the big horseshoe fill the field. This is the first summer of Mays. Watching Willie arrive is like hearing Charlie Parker for the first time. Angell is in the stands, probably wearing a fedora like the rest of the men. He is there as a fan, a role he proudly will retain as a baseball writer.

Tie game, eighth inning. Carl Furillo of the Dodgers, a righthanded pull hitter batting with Billy Cox on third, confounds the Giants with a screamer to the rightfield gap. Mays, positioned for Furillo’s pull power, sprints leeward. He makes the catch and, while still running away from the plate, slings a sortie of a throw to the catcher. Cox is out too. “I can still see the Dodgers players on the field and the Giants players in the dugout,” Angell says. “What? What was that? Get used to it, guys. I bring this up whenever I see Willie Mays. He never remembers me, which is O.K. But he’s impressed: ‘You were there? You tell them. Nobody believes me!’”

In long pieces published a few times a year, Angell has turned Bob Gibson as soft as a stick of butter under the noonday sun; sequenced like a geneticist the original Steve Blass disease; and, drawing on his first writing gig—when he tap‑tap‑tapped on a typewriter for a GI newsletter as a soldier stationed in the Central Pacific during World War II—chronicled the winning maneuvers and statesmanship of Joe Torre and Derek Jeter.

A lifetime of exquisite work—much of it anthologized in books such as The Summer Game and Once More Around the Park—will be honored on July 26 at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., where Angell will receive the J.G. Taylor Spink Award, the highest honor given by the Baseball Writers Association of America. Angell is the 64th writer to win the annual award but the first never to have been a member of the BBWAA. (The New Yorker does not cover baseball as a beat.)

“He is the best baseball writer in terms of talent, insights, the turning of a phrase, everything,” said Susan Slusser, the A’s beat writer at the San Francisco Chronicle who nominated Angell for the award. “I felt very strongly that there should not even be a writers’ exhibit in the Hall without Roger Angell.”

Now all he has to do is make it to Cooperstown. At the moment I have my doubts. We are in his weathered but game Volvo wagon, careening down Naskeag Point Road in Brooklin, Maine. Angell is behind the wheel; in fact, just about all of Angell is behind the wheel. Barely visible above its curved horizon are his blue cap, eyeglasses, white straw push broom of a mustache and both hands—set as hard as Quikrete at 10 and 2 o’clock. I am in the passenger seat, remembering that last month he told me his eyes were failing. In the map pocket in the door next to me are some Angell staples: a paperback Chekhov novel and two CDs, one by Roy Orbison and one titled Martin Scorsese Presents: The Best of Blues. The backseat is covered in enough hair from Andy, Angell’s beloved fox terrier, to knit a sweater. The asphalt rolls more than it climbs and falls, yet the Volvo groans and complains, sighs and exhales. It veers intermittently into the sand and gravel of the shoulder.

Oh, this is it. I know how this is going to end. We are headed straight to the graveyard, as sure as pocket Chekhov and lonely Orbison. It occurs to me that this is not a bad way to go. Brooklin, like Cooperstown, is near nothing and has changed hardly at all over the years. It might as well be the 1930s, when young Roger learned how to sail on wooden Beetle Cats at Center Harbor Yacht Club (established 1912; annual 2014 dues, $400) and wrote state officials in Augusta, “I am 15 years old. Please send my driver’s license.” As was the custom, they did.

Gone are his mother, Katharine Sergeant Angell White, the first fiction editor of The New Yorker; his father, Ernest, a lawyer; and his stepfather, E.B. White, an iconic figure in American literature. From a street-facing first-floor office in his house in North Brooklin, White wrote the children’s classics Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little. He also revised and enlarged the bible of good writing, The Elements of Style.

I suspect we are about to join them in eternity. In the near distance the waters of Eggemoggin Reach glisten in the late afternoon sun, as if winking slyly that the extravagant beauty of this place is to be kept secret. The sea off the fancy filigree that is the Maine coastline is speckled with little islands that suggest confetti in an enormous puddle of spring rain. Awaiting us is a narrow gate, not of pearl but of simple steel, topped by a graceful metal arch. It has the simplicity of the entrance to an old-time amusement ride. Angell points the nose of the Volvo toward the gate, and we are through to the other side.

Quiet falls.

I am reading the dates on the stones of the dearly departed, some of them sea captains lost to the ocean when it did more than just wink at them: 1901, 1848, 1853. . . .

Angell guides the Volvo as if paddling a wooden canoe. It undulates over the parallel tracks of sand and gravel in the grass, toward a majestic oak tree. We get out, the swinging doors giving a wheeze of either complaint or relief. Under the oak are three gray slate headstones with sloping shoulders and names inscribed in Centaur font. Here lie Katharine and E.B. and their son, Joel. At the foot of each plot is a headstone of spectacularly white Vermont marble with the same sloping shoulders and with a name in the same font. Here lie Callie, Roger’s daughter; Carol, his wife. . . . “And this is me right there,” he says, pointing.

Roger’s stone needs only a year of death after “1920–” and his body underneath. It occurs to me that this is the first time in my life I have stood next to a man standing on his own grave.

“Carol and I bought the plot about 20 years ago, next to the Whites,” Roger says. “The [graveyard keeper] said it was $120. I said, ‘Per year?’ And he said, ‘Nope, that’s it.’ For eternity. One hundred dollars for eternity.”

And then he laughs long and hard.

*****

To go back to the beginning, you have to go back to 1962, when New Yorker editor William Shawn, who wanted more sports in the magazine and wanted his writers to write about what interested them, approached Angell with a question: "You know about baseball?"

“A little bit,” Angell replied.

“Why don’t you give it a try? We don’t want it to be sentimental, and we don’t want it to be tough.”

Angell was 41. He was a New Yorker editor who had written a few baseball pieces for Holiday magazine. He decamped to spring training in Florida, where his natural shyness and his uncertainty around the clubby world of baseball—including the hothouse of cynicism known as the press box—prompted him to come back with a story that quoted not a single player or manager. “The Old Folks Behind Home,” in which he gave voice to the senior citizens enjoying the rites of spring, barely dipped a toe into the pool of baseball reportage, but it was Angellic nonetheless.

Casey Stengel, the ancient manager of the just-birthed Mets, was “a walking pantheon of evocations,” Angell wrote. Early Wynn, then 42, “pitched carefully, slowly wheeling his heavy body on the windup and glowering down on the batters between pitches, his big Indian-like face almost hidden under his cap.” Angell noticed Whitey Ford pitching for the Yankees while Warren Spahn threw in the Milwaukee Braves’ bullpen—two of the best lefthanders in history in the same line of sight, as if one were the thrown shadow of the other. “It excited me to a ridiculous extent,” Angell wrote. “I couldn’t get over it.”

“It was fun! Wow!” he recalls of the assignment. “I liked it, and people seemed to like it. The main thing is, I had all the space to write.”

We are seated in the front row of the press box at Yankee Stadium in June, with a dull home team challenging a first-place but unconvincing Blue Jays squad. Baseball never has been more incidental to people at stadiums than it is now, the actual game made smaller by too-loud music, inescapable commercials, mobile technology and myriad food and retail options. “They line up to go eat in the middle of the game, which amazes me,” Angell says.

The press box is no different. Heads are down, buried in laptops, tablets and smartphones. Angell, device-free, sees only the game, and he captures its most interesting elements with doodles and notes in a Mead three-subject notebook with the slightly rough paper he cherishes. Because those notebooks are extinct, Angell resuscitates his retired ones that still have blank pages. This one is from September 2005. It includes a doodle of Yankees outfielder Hideki Matsui; the drawing helped Angell remember the thickness of Matsui’s chest and the width of his face.

“The replay amble,” Angell says as Toronto manager John Gibbons takes the now familiar stroll on the field while his dugout lieutenants decide whether to challenge a close play at second base. Angell is such a keen observer that his old friend Bill Rigney liked to say he would have made a good scout. He knows swings the way he knows writing styles. Joe DiMaggio’s, he says, “had tremendous torque, with wide feet. It was a line-drive swing.”

Brian McCann, New York’s kindly bear of a catcher, is at the plate and keeps fouling off pitches, seeming to bend the pitcher’s spirit with each one. “That’s a nice swing,” Angell says. “It’s got a little Will Clark in it.” McCann rips the next pitch into the rightfield seats for a two‑run homer.

Space and time are the rare earth metals of writing, and Angell has enjoyed mother lodes of both. Moreover, as a writer and fiction editor at a literary magazine, he began unshackled by J‑school and newspaper-reporting conventions, in which the writer must leave himself and his rooting interests out of the copy. As a young man Angell admired the work of Red Smith, the literate newspaper columnist “who was funny and lighthearted and never sentimental,” he says. “He put himself into his writing without effort. I remember his best last line ever. It was after the near no-hitter- by [Bill] Bevens in ’47, when Cookie Lavagetto got the winning hit. ‘The unhappiest man in Brooklyn is sitting up here now in the far end of the press box. The v on his typewriter is broken. He can’t write either Lavagetto or Bevens.’

“It had broken off his typewriter and it went like this,” Angell says, pantomiming a flying key. He laughs long and loud.

There was another formative influence. Seventeen months before Angell went to Florida on his first baseball assignment for The New Yorker, the magazine published the most famous baseball essay in history, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” by John Updike, in which the author observed Ted Williams entirely from a seat in the Fenway Park stands. Angell, as the magazine’s fiction editor, edited Updike for years. They became so close that Updike would read two versions of the same sentence aloud to Angell and ask, “Which one sounds better?”

“That piece and my writing are very much alike in that he wrote about himself writing about Ted Williams, which I always have done,” Angell says. “I have always put myself in my pieces, almost always as a fan.”

A bit of quintessential Angell and a last line that belongs with Red’s: It is the summer of 1969, and Angell tries to decide which baseball he likes best, having sampled the Miracle Mets at Shea Stadium, the fledging Montreal Expos in the country-fair setting of Jarry Park and the bat-banging percussive might of the Red Sox and the Orioles at the Fens. “Then I remembered that I didn’t have to choose, for all these are parts of the feast that the old game can still bring us,” he wrote. “I felt what I almost always feel when I am watching a ball game: Just for those two or three hours, there is really no place I would rather be.”

By then Angell, more comfortable in the baseball cocoon, was adding expert reportage to his observational skills. He sought out the good talkers and had the manners and skill to elicit their most honest thoughts. Blass, a righthander who suddenly lost his ability to throw strikes, opened up to him as he had to no other writer. The Red Sox legend Smoky Joe Wood sat with Angell at a Yale–St. John’s game that turned out to be a classic duel between future big leaguers Ron Darling and Frank Viola. Pitcher David Cone, in his first three hours with Angell on a book collaboration, told such deep, moving stories about his childhood and his alcoholic father that Cone’s wife, Lynn, said in amazement, “I’ve never heard any of this!”

And then there was Gibson, the notoriously stern Cardinals ace who regarded reporters as he did poison sumac. “I never worked harder to set it up,” Angell says of the interview. “I was terrified. Gibby brings me to his house and he gives me a swimsuit, and we’re sitting by the side of his pool, and for three or four days I’m with him all the time. And he’s telling me every single thing I want to know. When the piece was finished, he sent me a picture of himself and wrote, ‘The world needs more people like you.’”

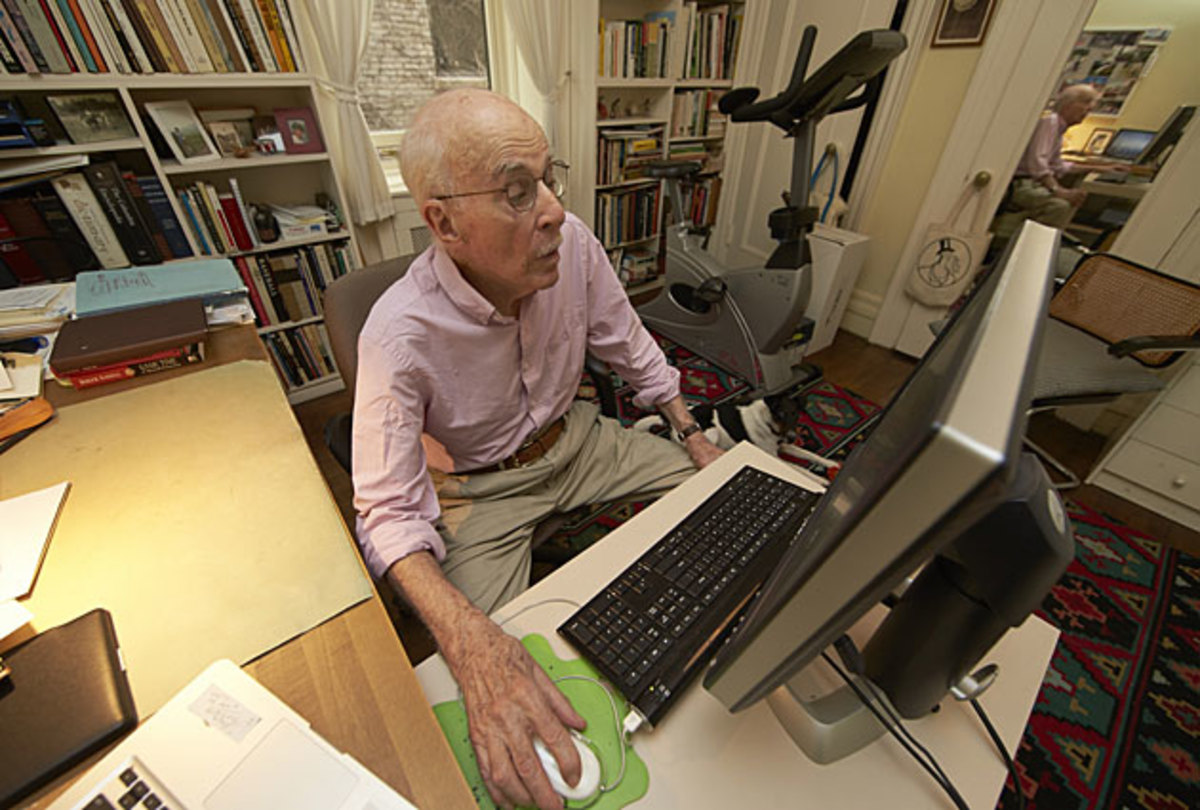

Angell is remarkably fit and sharp at 93. He blogs occasionally and goes to The New Yorker’s office for an hour or two each workday, often reading fiction submissions. He is a repository of so much baseball and U.S. history—from Babe Ruth to the Pacific Theater to Jackie Robinson—that conversing with him is like thumbing through an encyclopedia; half the fun is not knowing where you will wind up next.

Ruth? As a kid Angell used to see him walking around Manhattan, “always in a camel hair coat.” Lou Gehrig? Angell remembers being at the ballpark on April 29, 1933, when Senators catcher Luke Sewell tagged out two runners—Gehrig and Dixie Walker—at the plate on the same play. It was a strange play that involved four Hall of Famers: Gehrig and Walker were on base; Tony Lazzeri hit the ball to right center-field, where it was fielded by Goose Goslin, who threw to Joe Cronin, who threw to Sewell, who tagged out Gehrig and Walker as if they had just been flung from the same revolving door. (Only Sewell and Walker aren’t in Cooperstown.)

The fan in Angell is malleable. He grew up in Manhattan so attached to the Giants and Carl Hubbell, the great screwball pitcher, that as a teenager he would walk with his pitching arm cocked with the palm out, the way Hubbell’s weary left arm hung—until- Katharine told him to knock it off. He became a fan of the A’s when he got to know owner Walter Haas; a fan of the Mets when they owned New York’s attention in the 1980s; and a regular fan of the Red Sox because of his summer roots in Maine. But he holds a soft spot for the Yankees, largely because of Torre, the former manager who will be inducted into the Hall of Fame the day after Angell is honored.

“Joe Torre is the No 1 New York public figure of our time,” Angell says. “He never embarrasses himself, and he does it without effort. Just astonishing. He has immense natural grace and decency.”

When Torre is told what Angell said of him, he replies, “I’m getting goose bumps just listening to that. I’ve known Roger since my playing days. What caught my eye from the beginning was the way he went about his job. He was not doing it to get attention. He’s an artist. I’ll be honest: I thought he was already in the Hall of Fame.”

Down below, the Yankees and the Blue Jays are dragging their heels. “It’s ridiculous,” Angell says about the pace of play. “There’s no reason why they can’t speed it up. I blame the commissioner and the umpires.” And something else is happening to baseball. The emotional connection between the fan and the game has lessened. “They’re not paying attention in the same way,” he says. “Nobody’s keeping score.” Nothing, he says, has changed baseball more than TV. Replay has become our external hard drive, rendering nearly moot the idea of carefully cataloging something in memory.

“I can still see in the mind’s eye plays that happened generations ago,” he says. “And I do care. It’s going to be a bit harder for us to care because we have access to great moments and players every night over and over. Replay is fabulous, but it takes away the feeling. I asked Carlton Fisk about his memory of the 12th-inning home run in 1975. He said, ‘I leave the room whenever it’s coming up [on TV]. I’m trying to keep something private, just in my head.’

“If you’re going to see something once, you are going to put it away. If you see it time and time again, it doesn’t mean as much. It sounds like I’m heartbroken, but I’m O.K. It’s just different.”

Angell’s greatest contribution to the game is that in his writing he has preserved the great people and moments with such grace and care. He is the curator of our baseball souls. Reading Angell on Fisk’s home run is as different from seeing the highlight as falling deeply in love is from speed dating. The beauty of these words, in “Agincourt and After” (1975), is the amber to preserve our emotional connection to the game:

It is foolish and childish, on the face of it, to affiliate ourselves with anything so insignificant and patently contrived and commercially exploitative as a professional sports team, and the amused superiority and icy scorn that the non-fan directs at the sports nut (I know this look—I know it by heart) is understandable and almost unanswerable. Almost. What is left out of this calculation, it seems to me, is the business of caring—caring deeply and passionately, really caring—which is a capacity or an emotion that has almost gone out of our lives. And so it seems possible that we have come to a time when it no longer matters so much what the caring is about, how frail or foolish is the object of that concern, as long as the feeling itself can be saved. Naïveté—the infantile and ignoble joy that sends a grown man or woman to dancing and shouting with joy in the middle of the night over the haphazardous flight of a distant ball—seems a small price to pay for such a gift.

*****

|

|---|

Begging your pardon, an amendment: The beginning was not 1962 in New York City. It was here, in Maine. Summers here the young Roger learned not only how to sail and how to drive but also how to be a writer. Every Monday, E.B. White, known as Andy to friends and family, would cordon himself in his North Brooklin office and suffer through all the whirring and clicking of the gears, flywheels and levers of focused thought. He would emerge briefly for a wordless lunch and then retreat again. Hours later he would reappear, this time with his weekly “Comment” piece for The New Yorker ready to be mailed off, and harrumph, “It’s not any good.” (I ask Roger if he is similarly demanding of himself, and he says, “Yes. Aren’t we [writers] all?”) Days later Roger would read his stepfather’s work and be amazed that such suffering produced something “so lighthearted and with such easy flow.”

In 1961, at a spring training B game in Orlando, catcher Norm Sherry told Koufax, who had nearly quit after the previous season because of chronic wildness, to take a little off his fastball to find the strike zone. It worked. Koufax threw seven no‑hit innings. It was the beginning of his march to pitching immortality. Koufax would later explain his apotheosis as “taking the grunt out of my fastball.” What Angell understood and mastered was taking the grunt out of writing. White showed him the way.

“Be clear,” Angell says. “You can write long, but be clear. And remember, you are speaking to the reader. It’s a letter to the reader.

“I used to have a terribly hard time starting, because when I wrote I didn’t do first drafts. I wrote the whole piece on typewriters and would x out and use Scotch tape. I think I began to realize that leads weren’t a big problem. You can start anywhere.”

Angell openers: “Baseball has begun” (1968); “I first heard about the death of baseball one night last December” (1969); “Sports are too much with us” (1971); “Consider the catcher” (1984).

“Don’t look at my clothes.” That is not an Angell lead. It is a request he makes as we ascend the staircase in his Brooklin house toward the closet in his bedroom. Angell’s home is a little wooden envelope of good cheer, the timber warm and light-hued. He bought the place in 1975.

He says, “I want you to ask yourself an important question that can be answered yes or no, O.K.?” We are standing in his all-wood closet. In front of us are a framed picture of Carol and also an unframed 8‑by‑10 of Roger in his Army Air Force uniform, typing away for Brief, a cigarette dangling from his lips and a bramble of hair on his head. What he points to is something next to his photo. It’s a pushpin with a hairpin tacked beneath it. On the wall in ink Angell has written LITTLE JIFFY DECISION MAKER. In a circle around the pin, like numbers on a clock face, are words such as sure, absolutely and of course. On the bottom, where the 6 would be on a clock, is no. He says, “Are you ready?”

Angell gives the hairpin a spin. Of course, by the laws of gravity, there is only one place for the Jiffy Decision Maker to stop. He is beside himself with giggles.

“Would you like to see the town?” he says. Our first stop is the yacht club. Angell points to the Beetle Cats, the Haven 12 1⁄2s, the Herreshoff 12 1⁄2s and one red Herreshoff Fisher’s Island 21, which was built in 1930 and is one of only “about 20 in existence,” he says. “That’s the Greta Garbo of our fleet.”

We press on in the utilitarian Volvo, our anti-Garbo. “I’m going to show you the boatyard,” he says. “Andy’s son, Joel White, my late brother—this was his yard. It wasn’t nearly this big then.”

We pass the post office, the general store and the library and head down Neskeag Point Road. Roger drove here with his new license in 1936, the year a kid named DiMaggio, just six years his senior, broke in with the Yankees. “This is where my [three] children and my grandchildren learned how to drive. Every one of them! Ha, ha, ha!”

We swing past another harbor, this one belonging more to fishing boats and lobster boats. There are harbors and coves and inlets at almost every turn. Maine, the sea air, the memories, the deep comfort of one of the last unchanged corners of the world—the whole of Brooklin fills Angell with energy and light. In order to keep his mind sharp for writing, he has been memorizing poems. Ogden Nash’s A Drink With Something in It, a humorous ode to the martini, is his latest mental calisthenic. “Would you like to hear that?”

“Of course.”

Angell nails every word of the nine-line poem, and once again the Volvo fills with laughter. I think about something he told me back at Yankee Stadium. “What’s so interesting to me in writing about baseball,” he said, “is the number of people I talked to who really gave their lives to me. Bob Gibson. This woman named Linda Kittell. She married a semipro pitcher. I spent a week with them in Vermont. She just died this past winter. She was a professor. She said, ‘We’re giving you our lives.’”

I never understood that responsibility as profoundly as I do now, in such a private, happy space of someone with such an epic life—especially now that we have passed under the metal arc of the Brooklin town cemetery. This is where the journey ends: under the big oak tree, the one Andy planted when Katharine died in 1977. The Angells’ headstones are designed to match the Whites’ in everything but the stone. Roger consulted an art director at Newsweek to get the font just right. Carol and Roger had a discussion before settling on the white marble.

“It’s still pretty white, but it will get grayer,” he says. “I thought it was ostentatious, but there’s a lot of white stones back there, so it will be O.K. in time.”

The arc at the top of Carol’s headstone is decorated with a line of neatly spaced sea glass, a custom Roger maintains. There is a supply of sea glass in a bowl in one of his upstairs bedrooms. Much of it washed up out of Eggemoggin Reach onto the rocky shore of their property.

“Carol loved sea glass and had a collection,” he says. He picks up a weathered peppermint-green shard. “This is the kind she loved most. From an old bottle. Sea glass is getting rarer. People aren’t allowed to throw [bottles] into the water.”

It is time to go. We fold ourselves back into the Volvo. “I really like that it’s a town cemetery,” Angell says. “I really like that.”

His headstone faces the gate. As you look through the gate and across the street, you see the First Baptist Church, built in 1853, a handsome white clapboard building that has a classic New England steeple toppled with a weather vane. “I like the top of this old church,” Angell says, and then, in an apparent appraisal of the view for eternity, he adds, “That’s not bad.”