The Hall of Fame chances for 2015's Golden Era nominees (Part 2)

Last week, the National Baseball Hall of Fame released the 10-candidate slate for this year's Golden Era Committee ballot, covering players and executives whose careers had their greatest impact between 1945 and 1972. At the upcoming winter meetings, a 16-member panel of Hall of Fame players and managers, as well as writers and former executives, will vote on the candidacies of nine former players and one executive. Those who receive 75 percent of the vote will be inducted into Cooperstown next summer. The results will be announced on Dec. 8.

On Friday, I dug into the particulars of the current process, as well as the first five of those candidacies, going in alphabetical order (Dick Allen, Ken Boyer, Gil Hodges, Bob Howsam and Jim Kaat), so here I'll address the remaining five: Minnie Minoso, Tony Oliva, Billy Pierce, Luis Tiant and Maury Wills. Minoso, Oliva and Tiant — all Cuban-born, incidentally — are holdovers from the last Golden Era Committee ballot, from which only the late Ron Santo was elected in December 2011. Wills was most recently considered on the 2009 Veterans Committee ballot, while Pierce hasn't been on a ballot since dropping off that of the BBWAA in 1974; he was considered by the Historical Overview Committee for inclusion on VC ballots in 2003, '05, '07 and '09, but never made the final cut.

While I don't have a Hall of Fame vote yet, as you might expect when it comes to this discussion, I'm using my JAWS system to break down the candidates below. JAWS deploys Baseball-Reference.com's version of Wins Above Replacement to compare each candidate's value — career and peak (best seven years) — to the players already enshrined at his position. WAR accounts for each player's offensive and defensive contributions while adjusting for the wide variations in scoring levels that have occurred throughout baseball history, thus aiding considerably when it comes to cross-era comparisons and more clearly defining a player's core value. The current averages at each position:

position | number | career war | peak war | jaws |

|---|---|---|---|---|

SP | 59 | 73.4 | 50.2 | 61.8 |

RP | 5 | 40.6 | 28.2 | 34.4 |

C | 13 | 52.5 | 33.8 | 43.1 |

1B | 19 | 65.9 | 42.4 | 54.2 |

2B | 19 | 69.4 | 44.5 | 57.0 |

3B | 13 | 67.4 | 42.7 | 55.0 |

SS | 21 | 66.7 | 42.8 | 54.7 |

LF | 19 | 65.1 | 41.5 | 53.3 |

CF | 18 | 70.4 | 44.1 | 57.2 |

RF | 24 | 73.2 | 42.9 | 58.1 |

WAR-based numbers aren't all that should guide a player's Hall of Fame consideration. Awards, milestones, postseason and historical impact are part of the story as well. For more on that, see Friday's entry. The remainder of the candidates are listed alphabetically.

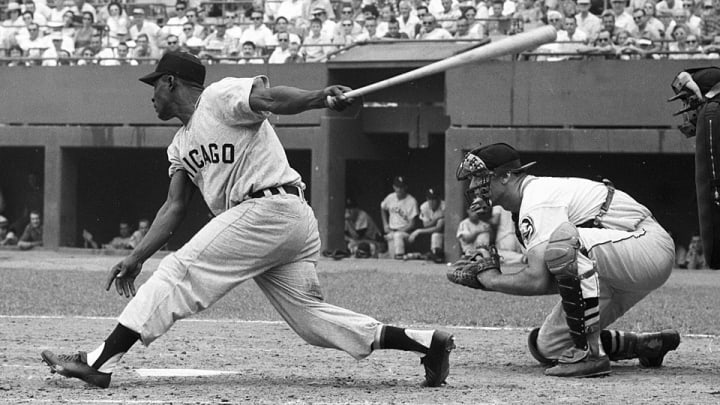

Minnie Minoso, LF (50.1 career WAR/39.8 peak WAR/45.0 JAWS)

The Hall of Fame chances for 2015's Golden Era nominees (Part 1)

Before the gimmickry of his middle-aged cameos, the Cuban-born Minoso was a dynamite all-around ballplayer, a speedster with an excellent batting eye and considerable pop who hit .299/.389/.460 from 1951-64, mostly with the White Sox. A nine-game debut with the Indians in 1949 and three-game and two-game stints with the White Sox at the listed ages of 50 and 54 in 1976 and '80, respectively, left his official career line at .298/.389/.459 (130 OPS+).

With an assist from Harlem Globetrotters owner Abe Saperstein, Minoso was signed by Indians owner Bill VeeckJr. in 1948 after three seasons with the New York Cubans of the Negro National League (Luis Tiant Sr. was a teammate). During his time in the Negro Leagues, Minosos was the starting third baseman in both the 1947 and 1948 East-West All Star games and helped the Cubans to the Negro World Series title in '47.

Alas, Veeck sold the team after the 1949 season, and Minoso got lost in the shuffle, blocked not only by Al Rosen at third base but also by an outfield that included AL integration pioneer Larry Doby and All-Star Dale Mitchell. He spent most of '49 and '50 pulverizing Pacific Coast League pitching, and after eight more games with the Indians in 1951, was dealt to the White Sox, for whom he became the team's first black player.

Liberated by the trade, Minoso hit a sizzling .326/.422/.500 while leading the league in triples (14) and steals (31); he finished fourth in WAR (5.5) and second in the AL Rookie of the Year voting to the Yankees' Gil McDougald. That kicked off a killer 11-year stretch over which Minoso hit .305/.395/.471 (134 OPS+) with an average of 16 homers, 18 steals and 4.7 WAR per year. He was all over the AL leaderboards in that span, ranking in the top 10 in batting average eight times, in on-base percentage nine times (including five in the top five) and in slugging percentage six times. His OBP was boosted by his tendency to crowd the plate and take one for the team; he led the league in hit-by-pitches a whopping 10 times. Additionally, he led in steals and triples three times apiece, and in total bases once, with eight other top 10 finishes in that category as well.

Minoso ranked in the top 10 in WAR seven times, including the top five four times, and led the league in 1954 with an 8.3 mark. His 52.1 WAR over that 11-year stretch ranks eighth; everyone else from among the top 13 is already in Cooperstown. His talents received their share of recognition, as he earned All-Star honors seven times and won three Gold Gloves (though the award wasn't introduced until 1957), and while he never won an MVP award, he finished fourth four times, three in the 1951-54 span.

Hall of Fame rule changes a cruel twist to current crop of candidates

In December 1957, Minoso was traded from the White Sox back to the Indians; almost exactly two years later, he was traded back to Chicago, which means that he missed the latter's 1959 trip to the World Series. He was dealt again in November 1961, to the Cardinals, the first of three stops in three years before leaving the major league scene for a stint in the Mexican League that lasted well into his 40s. In 1976, Veeck — who by that time owned the White Sox again (as he had from 1959-61) — signed Minoso as a publicity stunt; as a 50-something pinch-hitter, he went 1-for-8. He returned in that capacity in 1980 (going 0-for-2), which made him the second player (after Nick Altrock) to spend parts of five decades in the majors. Commissioner Fay Vincent quashed the White Sox' attempt for another engagement in 1990, but the independent St. Paul Saints, owned by Mike Veeck, brought him back for one plate appearance in 1993, and another in 2003.

That whimsy probably had an effect on the way the BBWAA voters viewed Minoso's candidacy, and it did affect his eligibility. He received just 1.8 percent of the vote in 1969, and didn't again receive a vote until 1986, after five years had elapsed from his final major league appearance. By that point, most of the voters were far more familiar with those cameos than the heart of his career; he never drew more than 21.1 percent before his BBWAA eligibility lapsed after the 1999 ballot.

The big question on Minoso is how much of his major league career is missing due to circumstances beyond his control, namely baseball's color line and Minoso's age when it was broken, for there exists some uncertainty surrounding his birthdate. When he debuted for the Sox in 1951, they were just the sixth of the 16 major league teams to integrate, and he was believed to be 28, with a birthdate of Nov. 29, 1922. Other sources (including Baseball-Reference.com) say that he was born in 1925. Minoso has claimed both at various times, though in a 1994 memoir, he admitted to falsifying his age upon arriving in the U.S. in 1945 in order to obtain a visa, saying that the 1925 date was the correct one.

Regardless, Minoso was certainly prevented from becoming a major league regular at a time when his skills warranted it. That's an important consideration, because he finished with 1,963 hits and 186 homers, impressive statistics but hardly Hall-worthy, and his WAR-based numbers fall below the Cooperstown standards for leftfielders. Given that he starred in the Negro Leagues, that he posted 5.5 WAR in in his first full major league season (1951, believed to be his age-25 season) and that his seventh-best season — in a peak that's 1.7 WAR below the average enshrined leftfielder — is worth 4.0 WAR, the question is how much better his numbers would be if he had arrived earlier. Alas, nobody can answer definitively. Particularly given his decade-plus of dominance and his cultural importance as the game’s first black Cuban star and the first black player on either Chicago team (Ernie Banks integrated the Cubs in 1953), I'd have no problem voting for him.

Tony Oliva, LF (43.0/38.5/40.8)

Another Cuban emigré, Oliva spent his entire 15-year career (1962-76) with the Twins, and for awhile, he appeared to be Cooperstown-bound, winning a trio of batting titles, including a pair in his first two full seasons (1964 and '65). He hit .323/.359/.557 with AL highs of 217 hits, 43 doubles, 374 total bases and 109 runs in 1964, good enough to win AL Rookie of the Year honors and place fourth in the MVP race, then followed that with a .321/.378/.491 showing in '65 that helped the Twins win their first AL pennant; he finished second in the MVP vote that year to teammate Zoilo Versalles.

Oliva earned All-Star honors in each of his first eight full seasons (through 1971), led the AL in hits five times and won one more batting title (1971) while finishing second or third four additional times. For that span, he hit a combined .313/.360/.507 for a 140 OPS+, with an average of 22 homers and 5.3 WAR per year. He cracked the top five in WAR in four seasons, and the top 10 in one of the three slash stats 18 times.

In welcome change, a star-studded, modern group enters Hall of Fame

Unfortunately, a series of knee injuries — dating back to torn ligaments that required surgery in 1966 and '67 — diminished Oliva's effectiveness and cut into his playing time in his 30s. He tore cartilage late in 1971 and needed surgery, playing in just 10 games the following year. Even with a move to full-time designated hitter duty in 1973, he was never the same. He hit a combined .278/.331/.390 from 1972-76 and was worth a total of 0.5 WAR. He finished his career with 220 homers and just 1,917 hits, lower than any Hall of Famer from the post-1960 expansion era.

Via the WAR numbers, Oliva is about four wins shy of the rightfield peak standards, and a mile away from the career standard, so he's nowhere close on JAWS. What he might have done had his knees been stronger and with a more advanced state of sports medicine is compelling, but it's just not enough, not only in the context of enshrined rightfielders, but also when compared to Minoso, a pioneer who's more worthy of a vote here.

That said, Oliva has invariably polled better than Minoso in the Hall votes. When he became eligible for the BBWAA ballot, he received at least 30 percent in each of his last 11 years, with a high of 47.3 percent in 1988, his seventh year of eligibility. He made solid showings in front of the expanded Veterans Committee, consisting of all living Hall of Famers as well as Frick and Spink Award winners, receiving 59.3 percent in the 2003 balloting, 56.3 percent in '05 and 57.3 percent in '07; only Gil Hodges drew more support in the first of those three years, only Hodges and Santo in the second, and only Hodges, Santo and Kaat in the third. It wouldn't be a shock if Oliva is elected on this ballot, even though it contains more worthy choices.

[pagebreak]

Billy Pierce, SP (53.2/37.8/45.5)

An undersized (5-foot-11, 160 pounds) southpaw, Pierce was the AL's best pitcher in the 1950s according to WAR (43.7) while running second in both ERA+ (128) and wins (155). Had each league issued its own Cy Young award — which didn't happen until 1967, 11 years after the first one — he likely would have taken home some hardware. As it was, in a career that covered 18 years (1945, 1948-64), Pierce went 211-169 with a 3.27 ERA (119 ERA+), helping both the 1959 White Sox and 1962 Giants to pennants.

The JAWS 75 for 75: Ranking the Hall of Fame's top players

Initially signed by the Tigers but traded to the White Sox in November 1948, Pierce battled control issues early in his career, walking more men than he struck out in his first three seasons of substantial work (1948-50), though he began to emerge as a solid starter. His career took a step forward when manager Paul Richards had him switch from a curve to a slider, which helped him cut his walk rate in half and lower his ERA so much that he placed in the top six in that category in 1951, '52 and '53. During the last of those years, he went 18-12 with a 2.72 ERA (second in the AL) and a league-high 186 strikeouts en route to the circuit's top WAR (6.3). After an off season in '54, he led in both ERA (1.97) and WAR (6.9) in 1955 and reached the 20-win plateau in '56 and '57. With a cast that included Minoso, Hall of Fame double play combo Nellie Fox and Luis Aparicio, and later Larry Doby as well, the Sox averaged 89 wins a year from 1953-58, though they never finished higher than second.

They finally broke through in 1959, winning 94 games and the pennant, but by that point, Pierce had been surpassed by Early Wynn (acquired from Cleveland in a deal for Minoso in December 1957) and Bob Shaw as the team's best starter; he was limited to bullpen duty in Chicago's World Series loss to the Dodgers. Traded to San Francisco after the 1961 season, Pierce turned in a strong season (16-6, 3.49 ERA) in helping the Giants outlast the Dodgers, then made two strong starts, including a complete game win in Game 6 of the World Series against the Yankees. He placed third in that year's Cy Young balloting behind Don Drysdale and Giants teammate Jack Sanford, but he didn't have much left in the tank after that, winning just six games over two more seasons.

From an advanced metrics standpoint, while Pierce ranked in the league's top five in WAR six times, he's far off the pace on all three WAR-related fronts, and he ranks just 97th among starters in JAWS, four notches ahead of Kaat. He barely got the time of day from the BBWAA voters, lingering in the 1-2 percent range in five years on the ballot (1970-74). He's never gotten onto any Veterans Committee-type ballot before, and while he's finally here, that's probably as far as he deserves to get.

Luis Tiant, SP (66.7/44.6/55.6)

The Cuban-born son of legendary Negro Leagues pitcher Luis Tiant Sr., Tiant was as colorful a character as the island produced, known for his fu manchu mustache and ubiquitous stogies — which he would even take into the shower — as well as his unique deliveries. Best remembered for his eight-year stint with the Red Sox (1971-78), he pitched for six major league teams over the course of his 19-year career (1964-82), finishing with a 229-172 record and a 3.30 ERA (114 ERA+).

The JAWS 75 for 75: The Hall of Famers who just missed the cut

Tiant pitched in the Mexican League in 1960 and '61, but didn't return to Cuba after the latter season out of fear that he would be banned from further outside travel. Signed by the Indians in 1962, he debuted in the majors in '64, when he was (allegedly) 23. After four mostly good seasons while bouncing back and forth between the bullpen and the rotation, he broke out in 1968 — the "Year of the Pitcher" — to lead the AL in ERA (1.60), shutouts (nine, including four in a row at one point) and WAR (8.4), going 21-9; alas, Denny McLain's 31-6 season with a 1.96 ERA took home the league's Cy Young honors. Tiant slumped dreadfully the following year, losing 20 games and more than doubling his ERA, and while battling injuries and ineffectiveness, he passed through the hands of the Twins and Braves before winding up in Boston.

Though his 1971 was dismal, he rebounded to lead the AL in ERA (1.91) again in '72, and emerged as the team's staff ace, reaching the 20-win plateau in 1973 and '74, and helping the Red Sox to the 1975 pennant. After throwing a shutout in Game 1 of that classic World Series, he returned on three days' rest to gut out a complete-game victory in Game 4, "delivering 163 pitches in 100 ways," as Sports Illustrated's Roy Blount Jr. described it, and he started the legendary Game 6 as well. That year, the great Roger Angell classified six aspects of his deliveries in an essay later collected in Five Seasons; two of them were:

1) Call the Osteopath: In midpitch the man suffers an agonizing seizure in the central cervical region, which he attempts to fight off with a sharp backward twist of the head.

4) Falling Off the Fence: An attack of vertigo nearly causes him to topple over backward on the mound. Strongly suggests a careless dude on the top rung of the corral.

After departing the Red Sox, Tiant spent two years of diminishing effectiveness with the Yankees and then brief stints with the Pirates in 1981 and the Angels in '82 before retiring.

As colorful as Tiant's career was, his Hall of Fame case is more black-and-white. He earned All-Star honors just three times, and never placed higher than fourth in a Cy Young vote, though he did rank in the top 10 in WAR eight times. He notched far fewer wins than nine of the 10 contemporary starters already enshrined, six of whom reached the 300 plateau (Steve Carlton, Phil Niekro, Gaylord Perry, Nolan Ryan, Tom Seaver and Don Sutton) and three more of whom (Bert Blyleven, Ferguson Jenkins and Jim Palmer) had at least 268; among that cohort, only Catfish Hunter (224) had fewer. Via the advanced metrics, Tiant is about seven wins off the career WAR standard for enshrined starters, and six off the peak; he ranks 52nd in JAWS, below all but Sutton (50.7) and Hunter (38.2) from among those aforementioned contemporaries, and below all but 22 of the 59 enshrined pitchers.

Tiant never made much of a dent in the BBWAA voting, debuting at 30.9 percent in 1988 but never topping 20 percent again. He doesn't figure to have much of a shot here, but there are worse things the voting panel — and you, the reader — can do than watch The Lost Son of Havana.

Maury Wills, SS (39.5/29.5/34.5)

A switch-hitting shortstop in the majors for 14 seasons (1959-72), mostly with the Dodgers, Wills is generally credited with reviving the art of the stolen base, a particularly useful tactic in the run-parched environment of Dodger Stadium in the early-to-mid '60s. Wills led the league in steals every year from 1960-65, setting a since-broken major league record in 1962 with 104 — a performance that helped him earn NL MVP honors — while playing a significant role on three Dodgers world championship teams.

One of a bevy of black players signed by the Dodgers in the wake of Jackie Robinson's breakthrough, Wills toiled in the minors for parts of nine seasons (1951-59) before getting a shot in the majors in mid-1959, at age 26. While his .260/.298/.298 showing was subpar, it still represented an upgrade over the even weaker performance of Don Zimmer, and he sizzled in September (.345/.382/.405) as the Dodgers won a three-way pennant race. Finding a home atop the batting order midway through the following season, Wills used his skills as a bunter and base thief to ignite Los Angeles' offense.

Rule change to Hall of Fame ballot isn't death blow for steroid era

After stealing 50 bases in 1960 and 35 in '61, Wills swiped a whopping 104 — a mark that stood until broken by Lou Brock in 1974 — in 117 attempts in 1962, that while batting .299/.347/.373 with 10 triples and 130 runs scored; combined with defense that earned him a Gold Glove, he finished with 6.1 WAR. His performance was such a unique throwback that he beat out heavy-hitters like teammate Tommy Davis (.346/.374/.535, 230 hits, 27 homers, 153 RBI) to win the NL MVP award.

Alas, the Dodgers lost the pennant via a playoff to the Giants, but they would win the World Series in 1963 and '65, with Wills hitting for a career-best 112 OPS+ (on a .302/.355/.349 line) in the former year and stealing 94 bases in the latter before making a stellar showing (.367/.387.467) against the Twins (starring ballot-mates Kaat and Oliva) in the Fall Classic. Once his on-base percentages dipped, though, he fell out of favor. He was traded to the Pirates in 1967, then to the Expos in 1969 and then back to Los Angeles later that same year, where he finished his career in 1972.

Wills retired with 586 steals, 76 more than any other player from 1920-70, though his 73.8 percent success rate — and seven times leading the league in caught stealing — was not impressive. Nor was his batting line, even in the context of his environment (.281/.330/.331, 88 OPS+). The B-Ref version of WAR credits him with adding 55 runs on the bases in his career, but even so, he never dented the WAR leaderboard besides 1962, and neither his career nor peak WAR approach the standards of enshrined shortstops.

Wills received as much as 40.6 percent of the vote on the BBWAA ballot, reaching that mark in his fourth year of eligibility, but never topped 30 percent afterward, and he continued in that range on the expanded VC ballots. One has to grant him an extraordinary amount of credit for reviving the stolen base to justify voting for him. I just don't see it.

My virtual ballot

With 10 candidates eligible, the Golden Era Committee rules limit each voter to four slots. If I had a ballot, mine would include Minoso as well as Dick Allen, Ken Boyer and Bob Howsam, the lone non-player from among the 10, and the one on whom I reserved final judgment until I was certain I had space.

Given the history of the small-committee processes, which haven't elected a living player since Bill Mazeroski in 2001 and have elected just two 20th century players since (Joe Gordon for the Class of 2009, and Ron Santo for that of 2012), I'd be surprised at any result besides a shutout. That would be a disappointment given the number of worthy candidates, but as Santo and Hodges would tell you if they were here to speak, if there's one area at which this process excels, it's disappointment.