Brian Cashman: The Yankees' GM is an iconic and fearless figure

A version of this story appeared in the Aug. 24, 2015 issue of SPORTS ILLUSTRATED.

Consider the f-word.

Not officially: Officially, the four-letter bomb remains undroppable before mom or minister, and must hit the mainstream defused by dash or bleep. Other obscenities have lost clout, gone respectable, but f--- still provides the FCC and a keyboard’s top row with steady work.

Still, a part of us, the 10-year-old part, enjoys a good f-bomb explosion, its unspinnable, blast-wave honesty. Madonna on David Letterman in 1994, Dick Cheney on the Senate floor in 2004: Every decade has its profane episode to publicly condemn and secretly savor. “Felt better,” Cheney admitted, “after I had done it.”

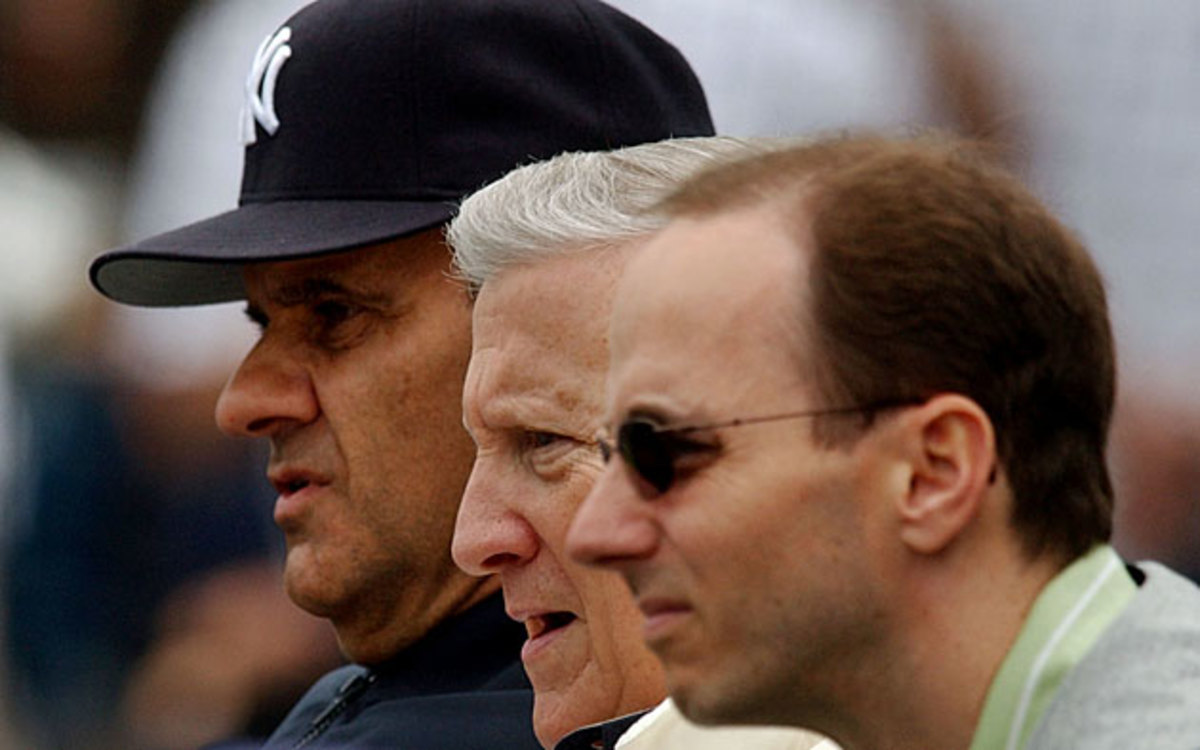

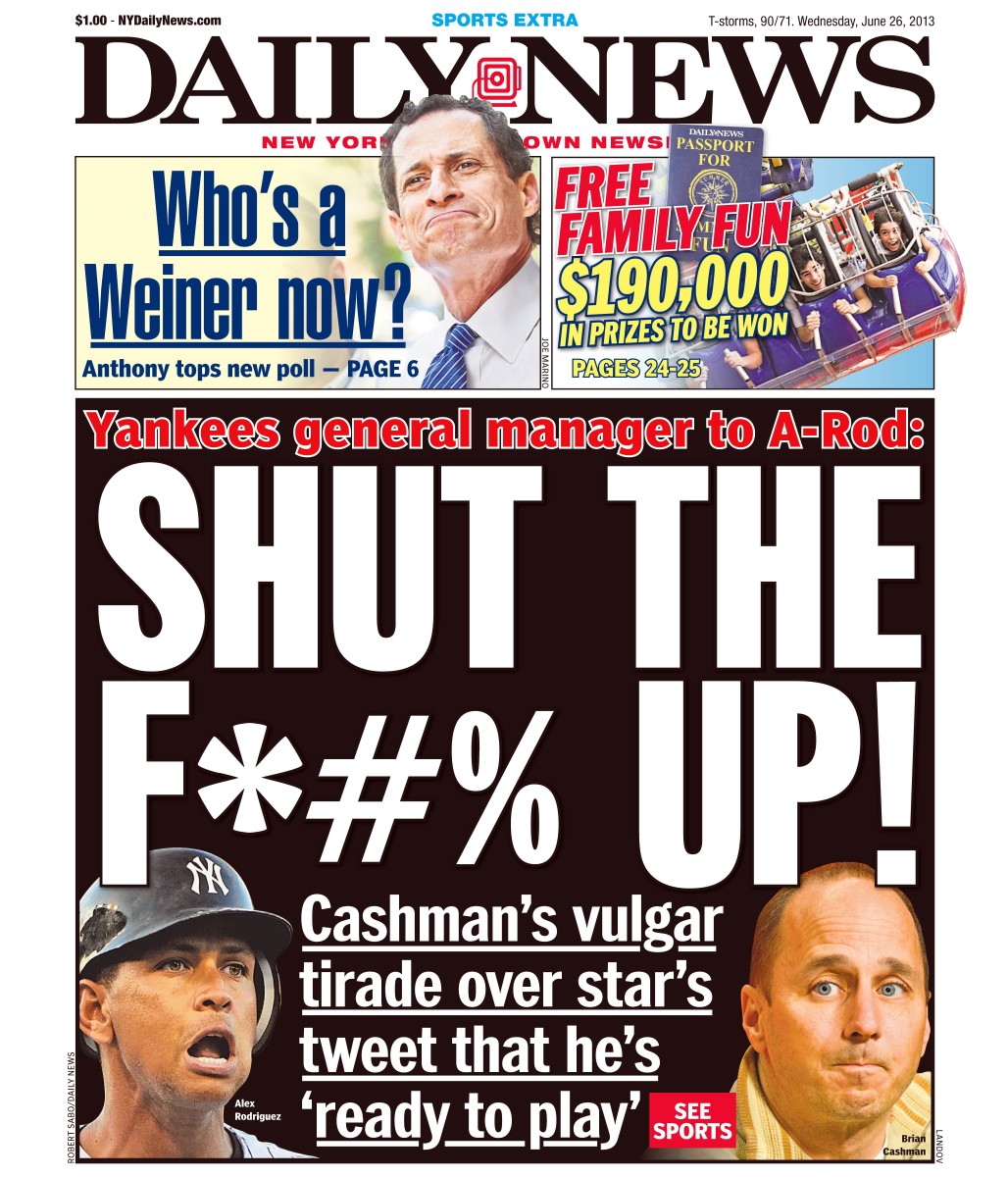

Brian Cashman won’t make that claim. How can he? As general manager of the Yankees he oversees the most-storied franchise in American sports, a job many would call far more serious than Vice President. So, no, the fact that during the team’s incendiary 2013 medical/legal/public relations war with its star slugger and serial PED abuser, Alex Rodriguez, Cashman delighted headline writers by snapping to a reporter, “Alex should just shut the f--- up”—that can hardly be an official point of pride.

“I blew my top,” Cashman says one Saturday last month in his office at Yankee Stadium. “I got calls from managers, general managers, agents, players. They were all, ‘I’ve been wanting to say that, good for you.’ But I was embarrassed. I conduct myself, for the most part, at a much higher standard than that.”

Return of Wright, offensive explosion have Mets in NL East driver's seat

Of course, he says this amid the bizarre matter of A-Rod and the Yankees now: Still together and, even stranger, peaceable and winning. Sure, there’s been a rise in f-bombs among the pinstriped faithful over the last three weeks, when New York’s seven-game late-July lead in the American League East dissolved, but who figured these Yankees to even have a lead to lose? Many factors—first baseman Mark Teixeira’s surgically repaired right wrist, the chasm left by retired shortstop Derek Jeter, the flimsy starting pitching—pointed to a third straight year out of the playoffs.

“That’s the beautiful thing, right?” says utilityman Brendan Ryan. “Everybody was counting us out.”

But then came Teixeira’s 30-homer revival, Didi Gregorius’s solid work at short, the lockdown closing of Andrew Miller and—most unlikely of all—a Rodriguez free of rust and off-field drama. After surgeries on each hip, at 40 he is crushing the ball harder than he has in six years, hitting .267 mostly as a DH with 24 home runs and 63 RBIs, the hub of one of baseball’s most potent offenses.

New York had hoped to be rid of A-Rod by now, had explored voiding the remaining five seasons and $114 million on his contract in 2013, and had spent much of the spring wrestling with the disposition of his tainted milestone bonuses (eventually donated to charity). Their strange-bedfellow relations remain cool at best, but at least there’s this: Rodriguez has, indeed, shut up. All season he has held himself uncharacteristically in check, refusing interviews, restricting his postgame comments to gratitude for a third (or is it a fourth?) chance and his desire to win.

“He’s been great,” Cashman says, voice going strikingly flat at the mention of Rodriguez’s name. “Whatever he articulates, it makes sense, and he’s supportive of his teammates, he’s humble, he’s throwing bouquets to the opponents, he’s respectful. He’s performed at an amazing level and, so....”

For all the credit due Rodriguez, any way you see it—suit versus player, 5' 7" balding nebbish versus towering alpha male, stoicism versus blather—the turnabout signals a clear victory for the 48-year-old Cashman. “The great part about watching Brian’s career,” says former Reds and Nationals GM Jim Bowden, “is that whether it be off-the-field personal issues or Yankees issues or George Steinbrenner issues, he was always able to rope-a-dope in the corner and figure out when to make the next punch, the next move. He knows when to lay low and when to step up, when you say something and when you don’t.”

Power Rankings: Seeking unlikely playoff berth, Rangers make big jump

Well, as the 48-year-old Cashman says, for the most part. The A-Rod f-bomb exemplified what has become, in recent years, Cashman’s increasing bent for blunt talk and risk-taking behavior. Some of it has been harmless, as when Cashman rappelled down a Stamford, Conn., high-rise in an elf costume or slept on a sidewalk to raise money for homeless youth. Some has been impolitic, like his publicly challenging Jeter during contract talks or calling critics “stupid” or “irritating” or “psycho.” And some has hurt: the fibula Cashman snapped skydiving, or the tabloid stories about the relationship that, in 2011, helped end his 17-year marriage, resulting in his allegedly being stalked and extorted, and that may well land Cashman in a witness chair to testify for the prosecution.

Such extracurriculars—not to mention his .594 winning percentage, four world championships and six AL pennants over 18 years—are rare, especially in an age when GM has largely supplanted manager as baseball’s vital job. But Cashman has never been easily categorized. If baseball execs these days seem to be either bland ex-scouts or bland metrics-mad wonderboys, Cashman occupies the slot for underestimated, L.L. Bean–styled grinds who delight in mixing the message. Why else point out, with eyebrows dancing, the paperweight front and center on his desk: steel Looney Tunes-ian bomb figurine, wick unlit, fronted with a lower-case f.

“A moment that I’m not proud of,” Cashman says again.

Of course he’s proud. He handled the player. He protected his team, Bronx style. But these are delicate days. The two men need each other now; indeed, with A-Rod’s help, this could be the year that Cashman proves himself not just diligent but wise; a master builder like the A’s Billy Beane or the Cubs’ Theo Epstein.

“At the same time,” Cashman says, reaching into a desk drawer, “I am a prankster.” And the custodian of Ruth, Gehrig and DiMaggio cocks and hurls a novelty paper snapper—crack!—at the wall covered by the name of every player in his system.

“I’ll walk you out and you’ll see,” he says. “I got a fart machine out in the hallway.”

*****

His rise? It’s like a sitcom sub-plot that began on a stoned whim, somehow clicked ... and then took on a life of its own. Steinbrenner’s Yankees were an executive chop shop in the decade before 1986, when Cashman hooked on. Office wags dubbed GM Woody Woodward the Pharmacist for his fortifying collection of prescription pills and medicines, and when, in ’87, Cashman saw Woodward buckling—Yessir, yessir, yessir—while the irate owner ordered that Woodward apologize for a trade that Steinbrenner had demanded, Cashman told himself, I would never want that job.

At least a half dozen far more proud and pedigreed baseball minds came through Steinbrenner’s revolving door in Cashman’s time, and only he held on. Around the office they called him—hell, he called himself—George Costanza, because his ascension to assistant GM in the early 1990s so neatly coincided with the bumblings of a short, bald Yankees exec on Seinfeld.

“It was totally surreal,” says Larry Rocca, one of Cashman’s teammates at Georgetown Prep in North Bethesda, Md. Rocca had grown up a baseball nerd, studying statistics and knowing every player. He considered himself perceptive, smart—in truth more devoted to the game’s minutiae than Cashman. Yet in 1996, covering the World Series for TheOrange County (Calif.) Register, Rocca happened upon his pal in the winning clubhouse—cigar in mouth, a step away from the top job. “Can you f------ believe this?” Cashman roared.

Not at first. But then Rocca flashed back to their senior year, when Georgetown’s powerhouse football program was depleted; the coach needed speed, and everyone kept talking about this second baseman, a boarder out of Kentucky who stole bases as easy as breathing. The coach was lucky. Cashman never minded looking foolish.

He had never played a down of football in his life. They tried him at punt returns, defensive back: Balls kept bouncing off his pads. He settled in at wide receiver but was still finding his locker-room bearings when he walked by a couple of starters, both bigger and quite tough. A hand yanked off Cashman’s towel, exposing him, and when he reached for it someone snapped a towel sharp against his ass. “Don’t do that again,” he said. When Cashman reached again, another towel snapped.

“Mother------, I told you to stop!” Cashman growled, and now he was standing there, fists clenched. “Completely naked, veins bulging,” Rocca says. “They’re fully clothed, and he’s ready to fight them both. He was pissed, but fearless. Then they all calmed down and it kind of just ... stopped.”

Cashman started every game. In the opener against D.C.’s Wilson High, Cashman blew a sure touchdown—60 yards of open field—when a pass slipped through his hands. Later in the year he caught a diving touchdown to beat archrival Bullis, but 30 years on he recalls only the failure. “Every now and then it’ll hit me,” Cashman says, “and I’ll wince.”

CC Sabathia's knee injury could be end of the line for Yankees' former ace

He treated sports like work, even then. His father, John, had run away from home on Long Island to work horses, standardbreds. Then came horse sales and auctions, then a 20-year stint as general manager of Castleton Farm in Lexington, Ky., with its 2,000-plus lush acres as well as Pompano Park in Florida, where George Steinbrenner and Whitey Ford came out to play.

“Nothing was a holiday,” says Cashman’s mother, Nancy. “When John and I traveled, we went to racetracks. Brian is like his father: It was business, period. Always on the phone. Other people wouldn’t tolerate it, but that was right, you know? Doing business while you’re having dinner.”

John became friendly with Steinbrenner, though the latter’s purchase of a stallion almost ended things. “The horse doesn’t work—take him back!” the Boss demanded. John refused. “George didn’t talk to him for a year,” Nancy says. “Then suddenly the horse started to perform, and he called: ‘The horse is doing well!’ ”

There were five kids, Brian in the middle. The Cashmans lived rich, rent-free in prime Kentucky horse country, but weren’t rich themselves. Everyone worked. Brian hated the horses; a blacksmith handed him a hot horseshoe once, and he never got over it. So then he got stuck with the worst jobs: collecting barn garbage on “maggot detail”; avoiding thrashing hoofs and teeth and holding the tail while a vet went shoulder-deep up a pregnant mare’s womb; shoveling placenta and manure out of steaming stalls. Escaping that for baseball was heaven. As a 12-year-old, Brian got locked inside an emptied Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati, and the anxious adults tried reassuring him through a gate. “Pick me up tomorrow!” Brian said.

Georgetown University rejected him. He got wait-listed at Boston College. Cashman thought he would walk on in baseball at Tulane, but two weeks before classes began, Division III Catholic University in D.C. guaranteed him a starting spot as a freshman. It was so late that the school, in a crime-blighted neighborhood, had no beds left. Cashman slept his first nights in a dorm hallway. “It’ll work out,” he said.

From the start he was one of Catholic’s best players, hitting leadoff, owning second base. The coach, Ross Natoli, loaded the schedule with Division 1-A opponents, and Cashman was susceptible to any pitch, he says, with a “wrinkle in it”, so right off he just ignored Natoli’s frantic, first-pitch ‘take’ signs. “I saw enough during warmups,” he’d say, and he was right: After roping another first-pitch triple to right center against George Washington, Cashman rose up from his slide muttering, “How’d you like that?” Natoli let him be. In 1988, Cashman set a school single-season record for hits, 52 in 38 games, that lasted 11 years.

Size was no issue. He stepped in fast when things got hostile in a bar, was the first to bark across the field, “One of yours is going down for that!” after a too-hard slide. “Any challenging situation, Brian was right there in the middle, and he would step in front,” says Matt Seiler, Cashman’s double play partner. “He was very serious, very intense. A very good judge of people. We’d meet someone the first time and say, ‘This guy seems nice,’ and he’d say, ‘No, he’ll let you down. This guy doesn’t have what it takes.’ ”

*****

The spring of his freshman year, during Catholic’s annual trip to Florida, Cashman’s father told him to head over to Pompano Park for a free meal; Nancy had already talked to George about a summer job. The track flack, one of the Boss’s buddies, flashed a 1978 World Series ring. “What if I can get you an internship with the New York Yankees?” the flack said.

So, yes: connections.

The day after classes ended in May 1986, Brian drove north and checked in for the summer at a Fort Lee, N.J., hotel. He’d get to Yankee Stadium by 8:30 a.m., spend hours transcribing the nightly game reports from all over the farm system, run stats out to all the necessaries, fetch the GM’s lunch, maybe take a player to the doctor. Nights, he’d work stadium security, keeping boozed-up fans from killing one another in the stands; it was midnight by the time he banged into his room, shirt often torn or bloodied.

There was one office rule, whispered: If you see the Boss coming, go the other way. Cashman’s baptism came when he got roped into driving Steinbrenner to a haircut and then to the airport. A combination of traffic, an unexpected bridge closure and Cashman’s confusion brought forth a barrage of f-bombs from the backseat. “You dumbass!” Steinbrenner said. Cashman hit a massive pothole, and the owner caught air. “This isn’t a f------ tank!”

Cashman came back for more the next two summers. It was a baseball kid’s dream, for the most part; the Mets owned the city then, but the Yanks always had their history. Once he was in the elevator when Mickey Mantle stepped in, and for one full floor it was just him and the Mick, lubricated. At Club Level the doors slid open, and the waiting clot of fans couldn’t believe their luck: Mickey! Mantle handed out a bunch of presigned baseball cards, sweet as could be. Then the doors closed. “How f------ dare you let these people f------ approach me?” he said.

“Then he stumbled off the elevator, and I went down to the clubhouse,” says Cashman. “He crushed me.”

Hit and Run: Mets' offense can't be stopped; Medlen shines for Royals

In 1989, Cashman graduated Catholic with a history degree and was mulling law school or a job with UPS when the Yankees dangled a position as baseball operations assistant. The way Bowden, just two months into his job as an assistant senior VP, recalls it, Steinbrenner walked the kid into the baseball ops office and into a crowd including Gene (Stick) Michael, Lou Piniella, Bob Quinn, Dallas Green and Syd Thrift. “I want to introduce you to Brian Cashman,” Steinbrenner said. “His dad is a good friend ... and someday you’ll all be fired and he’ll be the general manager of the Yankees.” Everybody in the room laughed.

Three months later Cashman escorted Bowden out. In July 1990, Steinbrenner began his 2 1/2-year ban for paying a gambler to dig up dirt on Dave Winfield, and Cashman spent the next two years in Tampa, as assistant farm director. With Steinbrenner sidelined, Michael took over the daily operations; Cashman grabbed his coattails, made himself indispensable. “Brian knew everything going on,” Michael says. “Nothing slipped by.”

When Cashman’s old basketball buddy from Catholic, Jimmy Patsos, was mulling the chance to work—unpaid—on the staff of Maryland head coach Gary Williams, Cashman told him to grab it. The chance to work for a high-profile program, even for nothing, was gold. Williams was known for his combustibility? Too bad. “Get close, learn from him and if he yells at you? None of that baby-s---, now,” Cashman said. “This is the real deal. Just take it and go in the next day and be ready to learn again.”

Who knew better? Michael elevated Cashman to assistant GM late in 1992, just months before Steinbrenner’s return, and he soon became one of the Boss’s favorite targets. The phone calls were relentless, the abuse humiliating. By ’96, Cashman had mastered the dull, vital details of baseball ops—contract rules, arbitration, administrative deadlines, keeping track of any throw-ins on deals that Steinbrenner promised and forgot—and yet was grinding his teeth so furiously at night that it sounded like chewing gravel. Friends urged him to seek counseling, but how would that help? Hadn’t he seen Steinbrenner angrier than he’d ever seen him, veins popping in his neck, the morning his ’96 World Series champions were about to parade through the Canyon of Heroes? “Why are wives on the floats?” the Boss screamed at three star players just hours after they’d brought him his first title in 18 years. “Get your wife off there or you’re gone!” And that’s when Cashman realized: You will never make him happy.

So he chose his spots, found ways to push back. “Who asked you? You’re just a f------ clerk,” Steinbrenner sneered during one front-office gathering, everyone staring down at their binders. Cashman waited a month, until details from an organizational meeting spilled into the Daily News and the New York Post and the drip-drip was driving Steinbrenner mad. “Who’s leaking this s---?” he demanded from the backseat one afternoon. “Was this you, Cashman?”

“No,” Cashman yelled back, holding up one of the tabs. “This says it was a ‘high-level Yankee official.’ I’m just a clerk, remember? I’m just a f------ clerk!”

In truth, George liked that. A part of Steinbrenner knew he had to be reined in and appreciated it when a loyalist like Michael stood firm. “You want this player?” Stick would say. “Fine. But I’m telling the media it was your idea.”

Cashman filed that away. He also saw Michael’s successor, Bob Watson, develop heart trouble and high blood pressure in his three years as GM and wanted no part of it. When Watson told Cashman he’d quit and recommended him, the 30-year-old spent a half hour begging him to reconsider.

On Feb. 3, 1998, the Yankees called a press conference at the Stadium. The elevator doors opened and Cashman walked down the hall, -the second-youngest GM in major league history, hand-in-hand with his wife, Mary. “This is a guy I’d never seen afraid,” says Larry Rocca, then a baseball writer at Newsday. “But he looked terrified.”

How Paul Goldschmidt turned himself into a perennial MVP candidate

When Cashman had accepted the job, in a lunch downtown with Steinbrenner on Groundhog Day, he insisted on a handshake, $300,000 deal for one year. Rocca gave him till mid-April, and nearly had it right: The ’98 Yankees started 1–4. “Stick, you’re going to have to go back in and take over,” Steinbrenner told Michael. “I don’t know if Brian can do this.” Michael stalled and reassured. “Give him some time,” he said.

“And then,” Rocca says, “they win 125 games.”

The Yankees won, in fact, three World Series in Cashman’s first three years, something no other big league GM—not even Ed Barrow, architect of New York’s 1920s dynasty—has ever pulled off. Problem was, everyone knew those were Michael’s teams, with the core of Jeter, Bernie Williams, Andy Pettitte, Jorge Posada and Mariano Rivera fostered by scouting savants Bill Livesey and Brian Sabean. There was no chance of Cashman’s being hailed a wünderkind.

His peers knew, though, that it was Cashman who, as longtime manager Joe Torre says, “had the courage” to ship folk hero David Wells to Toronto for the hated Roger Clemens in 1999. And it was Cashman who pulled off the stunning midseason trade with the Indians for slugger David Justice in 2000, a deal so immediate in its payoff—Justice was named ALCS MVP—that it still sparks envy. “It hit like a lightning bolt,” Beane says. “I don’t think anyone thought Justice was even available.”

Beane also credits Cashman with adjusting quickly to—and throwing all kinds of Yankees money at—the early 2000s analytics revolution Beane pioneered in Oakland. But the Cashman tool he fears is more basic. The two have been friendly since 1997, and no matter how casual the chat, Beane knows Cashman is taking exhaustive, always accessible notes. “Like a lawyer,” he says. “He’ll bring you—verbatim—a conversation you had regarding a player nine months earlier on some date in November when you were thinking about what size Butterball to pick up.”

In his two stints as a GM, Bowden completed four trades with Cashman. “I remember the last one, because it’s the only trade I beat him on—Johnny Albaladejo for Tyler Clippard,” he says. “Even the greatest GMs in the game, the John Schuerholzes, have traded David Cone for Ed Hearn or Adam Wainwright for J.D. Drew. But Brian doesn’t have a lot of those.”

He’s had his misses. Cashman bears the blame for acquiring Jeff Weaver, Carl Pavano and Kei Igawa, and for needing to be saved, in 1998, from signing the cancerous Albert Belle; expensive bets on outfielder Jacoby Ellsbury, catcher Brian McCann and now-depleted pitcher CC Sabathia may well never pay off. His influence has waxed and waned, sometimes by the week. Padres GM Kevin Towers knew before Cashman that the Yankees were signing Kenny Lofton in January 2004; a month later Cashman was back in the thick of it—sealing the financial sweeteners, massaging A-Rod’s concession to move from shortstop to third base—when New York traded Alfonso Soriano to the Rangers for Rodriguez. “Since Babe Ruth, probably the biggest move in franchise history,” Cashman says. “The Boss was so proud of that one.”

But by early 2005, Cashman was again getting overruled on free agents; everybody from the scouting director to agent Scott Boras to Steinbrenner’s pals seemed to have a hand on the 25-man roster. Dodgers owner Frank McCourt came calling, offering to double Cashman’s salary; it was only when he said “I’m not coming back” that Steinbrenner paid attention. “Why are you leaving me?” he asked. Cashman demanded—and got, in writing—full control of baseball operations. No GM under the Boss ever had so much clout.

“Cash still had people to answer to,” Torre says. “But once he signed that deal, it changed his demeanor. It gave him the authority to really do his job.”

Cashman didn’t want A-Rod back. When Rodriguez famously opted out of his 10-year contract during the 2007 playoffs, Cashman argued hard against the new 10-year, $275 million deal: A-Rod’s insecurities had become a headache, and would only be more of a burden without Texas covering $67 million of his contract. In what became the biggest, most crippling transaction of the post-Boss era—deteriorating health led Steinbrenner to cede control to his sons in ’10—Rodriguez’s star power proved too much for the Yankees and their YES Network to resist.

“The guy that made that decision,” says managing general partner Hal Steinbrenner, “is me.”

Manny Machado dazzling, starring at 3B—and he's still getting used to it

Yet if Hal became, as Cashman puts it, the “new sheriff,” Cashman hardly rode into the sunset. It was his call to replace Torre’s gut-level managing with Joe Girardi, whose by-the-book style leans happily on Cashman’s quantitative-analysis department. After Cashman’s flirtation with the Mariners further cemented Hal’s support, the GM personally landed Sabathia in the winter of 2008 amid the $423 million spending spree that resulted in the ’09 title. He’ll never have total control; in ’11, Cashman stated—at the welcoming press conference—that he was against the team’s signing of reliever Rafael Soriano. But it was also a sign that he has jarringly free rein to speak his mind.

“For certain players and people, it’s too much candor,” says Casey Close, Jeter’s agent. “He feels the easiest way to deal with something is to punch it right between the eyes. For some that’s the right mode. For players who need a softer approach, it’s like, Wow, that guy just hit me between the eyes.”

It was Cashman, too, who directed Jeter to patch up his public relationship with Rodriguez in 2006, and who before the ’08 season—after Torre neglected to do so—stunned the Gold Glove shortstop by demanding that he improve his diminishing range. Then, late in ’10, amid a contentious dispute over Jeter’s next contract, Cashman told reporters that the enormously popular star should “test the market” and try to find a better offer elsewhere. “If he can, fine,” Cashman said.

That he had little chance of winning so public a game of hardball didn’t seem to matter. Cashman calls Jeter “the greatest player I will have ever had,” but often admitted impatience with Jeter’s divalike tendencies. He likes being one of the few to tell the Captain no. During one of their last face-to-face meetings, in 2010, Jeter asked Cashman, “Who would you rather have playing shortstop this year than me?”

“Do you really want me to answer that?” Cashman said. Told to go ahead, Cashman instantly named the Rockies’ Troy Tulowitzki and was ready to list a few more. Wiser heads stepped in, but not before Cashman could say, “We’re not paying extra money for popularity. We’re paying for performance.”

Jeter signed a three-year, $51 million deal and finished his career in 2014 with a walk-off single in his final home at bat. But his relationship with Cashman never recovered.

“Sometimes honesty hurts,” Cashman says. “But if you’re being paid to do a job, do the job. You have to honor the job description; if not, you’re a fraud or stealing money. You can’t fake your way doing this. You either do it or you don’t.”

*****

How well does Cashman honor it? “If anybody else had done what Brian’s been doing, you know what’d be in front of his name? Future Hall of Famer,” Beane says. “There was a time I voted for him for Executive of the Year every year, regardless.”

Despite winning an average 96 games a year and missing the playoffs just three times, Cashman has never won that award and most likely never will. Cooperstown is no lock, either; only five GMs have made it in, and the franchise’s massive financial edge makes him easy to dismiss. Then again, Cashman never had the luxury—like, say, Epstein as the Cubs’ GM—of averaging 95 losses for three years.

“He survived in the biggest sports city in the world, the biggest media center, working for the toughest owner in the world—and delivered how many world champions?” says Watson. “The Yankees have been relevant since ’95. We’re talking about the kind of baseball man he is, and the type of man. He’s a survivor. A winner.”

Of course, Cashman’s decision to stand pat at the trade deadline—while division rival Toronto nabbed ace David Price and, yes, Tulowitzki—sets up a clear moment of truth. The Yankees’ inability to grow talent has been a two-decade knock: Since the rise of Jeter & Co., the farm system has produced just two everyday starters (Brett Gardner and Robinson Cano, now with Seattle). But now Cashman is loaded with primed prospects like pitcher Luis Severino, rightfielder Aaron Judge, first baseman Greg Bird and shortstop Jorge Mateo; Rodriguez’s revival helped convince him the time was now.

In mid-July, Cashman stopped A-Rod in the stadium parking lot. “We need anything?” Cashman asked. Not much, was the reply. If his slugger’s mouthings have irked Cashman in the past, no one questions Rodriguez’s baseball smarts. “I asked only because I know that he might have something to give. If it’s a good idea, I don’t care where it comes from,” Cashman says. He shrugs. “He likes our team.”

Indeed, like Rodriguez, whose 2015 surge has played out in an oddly feel-good zone, Cashman is now operating in a space beyond legacy. More A-Rod home runs? Whose mind will they change? Another title? A sudden collapse? Hal Steinbrenner considers any season out of the playoffs “embarrassing,” and if the Yankees lose the division, Cashman’s inaction at the deadline will not be forgotten. But whatever happens from here on out, it can’t really alter Cashman’s reputation. “I don’t have to prove myself anywhere,” he says.

George died in 2010, and Cashman’s own father passed with pancreatic cancer in ’12. September, early morning: Brian was in the room. The loss capped a brutal year. In February, Louise Meanwell, aka Louise Neathway, a 36-year British national with a history of harassment and protection orders, was arrested for allegedly extorting $6,000 from Cashman and was charged with grand larceny and aggravated harassment. He had been separated from his wife and two children for more than a year. Two days after the arrest Mary Cashman filed for divorce.

That case has yet to go to trial. In April 2012, Neathway was indicted on charges of lying to a grand jury. She has alleged in a countersuit that Cashman hacked into her email and threatened to have her committed—every detail widely reported in New York. In June she was convicted on nine counts, including grand larceny, in a separate case involving housing fraud, and faces a possible sentence of 15 years.

“I’m not going to talk about it,” Cashman says of his case. “I’m thankful it’s in the hands of the district attorney’s office. That’s all I’ve ever said publicly, and since that time I’ve been under siege.”

The Yankees have stood behind Cashman. Friends and family have watched him closely ever since, waiting for a crack. It hasn’t happened. “The Jeter thing was tough on him, and he never wavered with the personal stuff either,” says Patsos. “Some guys break down or they have a come-to-Jesus. But he’s always been the same guy.”

Every so often, on his lunch hour, Cashman will pedal his five-gear bike along the West Side Highway, six miles down past 42nd Street and back north again. He nearly got crushed once: Somebody ran a stop sign near Dinosaur Bar-B-Que. He doesn’t wear a helmet. “Adrenaline junkie,” Cashman says, and taken with the skydiving and high-rise scaling and the rogue f-bomb and everything else, it’s easy to assume a cliché. “I tease him: ‘You’re too young for a midlife crisis,’ ” says Yankees president Randy Levine.

“I call it living,” Cashman says.

So he hands shock pens to unsuspecting new scouts. He invents fake transactions for Hal and Levine, like the one in 2006 when he moaned for 10 minutes that the Mets had drafted pitcher Dellin Betances, now a star reliever for New York. Or, in the final few minutes before first pitch one night in July, Cashman walks outside his office to the corner between suites 45 and 46, near the giant photos of Andy Pettitte being heroic. He backs up to a nearby wall. A cluster of fans wanders by, and he clicks the button on a key-ring-sized remote. The sound is loud, unmistakable: They start and redden and wonder, Who just...? Cashman howls. A woman walks over.

“What’re you doing?” she says.

“Putting my fart machine on,” Cashman says.

He keeps pressing the button. Heads swivel, eyes narrow: Did you...? A small crowd gathers. Jim Leyritz, World Series hero of 1996, big homer in Game 4, back in baseball after years of turmoil, wanders up. The two men talk pitching, but Cashman’s thumb has a job to do.

“I got my fart machine,” he says.

“Is that what that is?” Leyritz says.

“This is my therapy, right here.”

A couple and a child: Gotcha! Cashman scans the hall for the next victim. Is it time? ... Now! “Too many burritos!” a man yells. He’s got to stop: First pitch soon, big game against the Orioles tonight. Time to honor the job description. But a part of him, the 10-year-old part, would be happy to stay here all night.