The Voice of Baseball: Get to Know Vin Scully, the Man Behind the Mic

Editor’s note: Legendary Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully died Tuesday night at age 94. Our cover story on Scully from 2016 details his reflections on his career during his final year behind the mic.

Rain lashed against the windows of Fordham’s Rose Hill Gymnasium, a 3,400-seat basketball facility cloaked in the style and masonry of a Gothic Revival church. Finely dressed attendees filed past the three double doors at the main entrance under the soaring archway with a cross at its crest. The gym’s gray Manhattan schist, the same stone that is bedrock to the city’s skyscrapers, acquired a more serious tone without the sun to twinkle its mica.

The nation’s oldest continuously used NCAA Division I basketball facility was built in 1925. Three years later, in the same neo-Gothic style and four miles away, the Church of the Incarnation rose on West 175th Street in Washington Heights. In between, in 1927, was born one of the most famous matriculates of both the university and the parish school, Vincent Edward Scully.

Scully, class of ’49, returned to Fordham to give the commencement address to the class of 2000. It was the first time he had returned since he and the Dodgers left Brooklyn for Los Angeles in 1958.

“I’m not a military general, a business guru, not a philosopher or author,” Scully told the graduates in the adjacent Vincent Lombardi Fieldhouse. “It’s only me.”

Only me? Vin Scully is only the finest, most-listened-to baseball broadcaster that ever lived, and even that honorific does not approach proper justice to the man. He ranks with Walter Cronkite among America’s most-trusted media personalities, with Frank Sinatra and James Earl Jones among its most-iconic voices, and with Mark Twain, Garrison Keillor and Ken Burns among its preeminent storytellers.

His 67-year run as the voice of the Dodgers—no, wait: the voice of baseball, the voice of our grandparents, our parents, our kids, our summers and our hopes—ends this year. Scully is retiring come October, one month before he turns 89.

One day Dodgers president Stan Kasten mentioned to Scully that he learned the proper execution of a rundown play by reading a book written by Hall of Fame baseball executive Branch Rickey, who died in 1965. “I know it,” Scully replied, “because Mr. Rickey told me.” It suddenly hit Kasten that Scully has been conversing with players who broke into the major leagues between 1905 (Rickey) and 2016 (Dodgers rookie pitcher Ross Stripling). When Scully began his Dodgers broadcasting career, in 1950, the manager of the team was Burt Shotton, a man born in 1884.

It is as difficult to imagine baseball without Scully as it is without 90 feet between bases. To expand upon Red Smith’s observation, both are as close as man has ever come to perfection.

“Los Angeles is a city of stars,” says Charley Steiner, a fellow Dodgers broadcaster for the past dozen years and, at home games, a regular 5:30 p.m. dinner partner with Scully and Rick Monday, another colleague. “And Vin is the biggest star of them all. I don’t care who it is—Arnold, Leo, Spielberg, Kobe, Magic—nobody is bigger than Vin, and I’ll tell you why: With everybody else you can find some subset of people who don’t like them. Nobody doesn’t like Vin Scully.

“Vin is our Babe Ruth. The best there ever was.”

Scully was named the most memorable personality in Dodgers history in a fan poll—beating all players—and that was 40 years ago. With Jerry Doggett, Scully formed the longest-running broadcast partnership in history—until his partner retired 29 years ago. Scully was inducted into the broadcaster’s wing of the Hall of Fame—34 years ago.

I am not in search of more tributes to Scully, nor, as appreciative though he may be, is he. “Only me” is uncomfortable with the fuss about him. He blanches at the populist idea that he should drop in on the call of the All-Star Game or World Series.

“I guess my biggest fear ever since I started,” he tells me, “besides the fear of making some big mistake, is I never wanted to get out ahead of the game. I always wanted to make sure I could push the game and the players rather than me. That’s really been my goal ever since I started—plus, trying to survive. This year being my last year, the media, the ball club, they have a tendency to push me out before the game, and I’m uncomfortable with that.”

Tributes are plentiful. What I am searching for is a rarity: Scully on Scully, especially how and why he does the incomparable—a man on top of his game and on top of his field for 67 years.

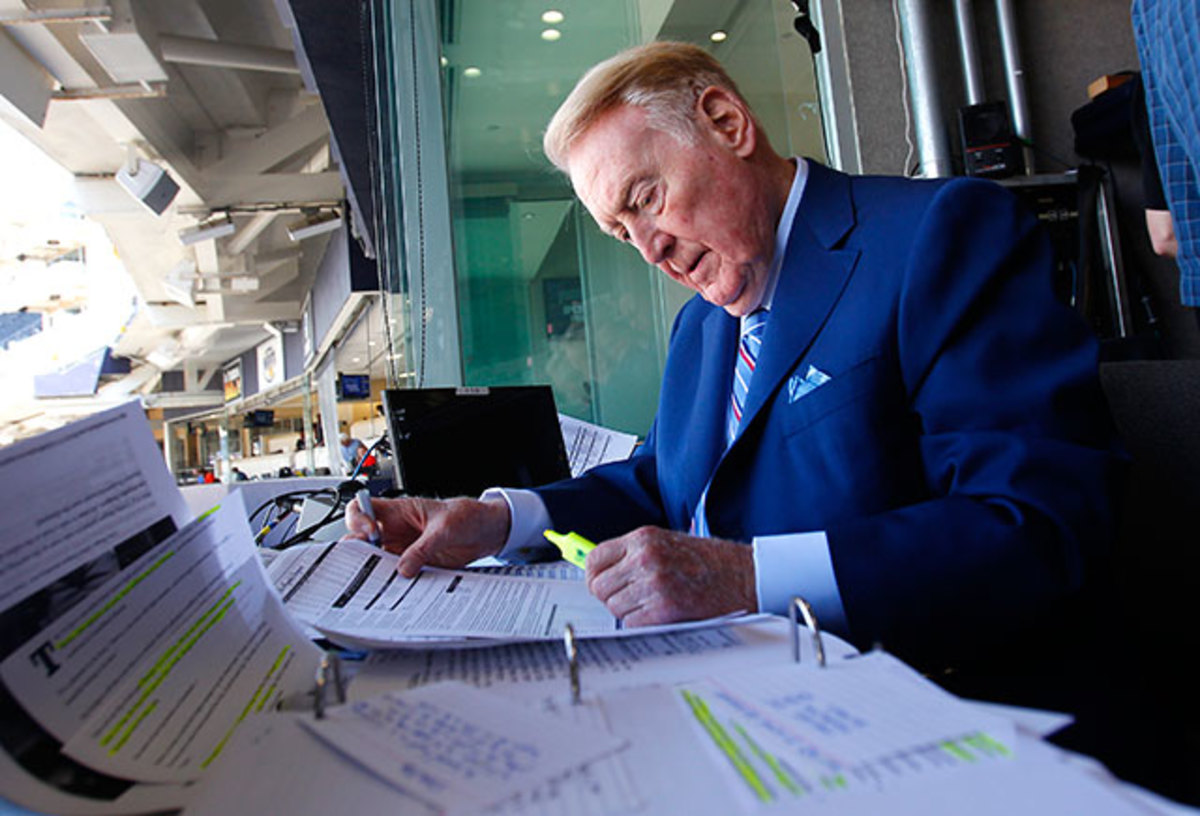

Vin is America’s best friend. (“Pull up a chair....”) He reached such an exalted position not by talking about himself, not by selling himself, or, in the smarmy terminology of today, by “branding” himself, but by subjugating his ego. The game, the story, the moment, the shared experience.... They all matter more. As I drive up Vin Scully Avenue toward the Vin Scully Press Box (more tributes) to meet with Vin Scully last month, I worry that getting Scully to turn his perspicacious observational skills on himself may be harder than Manhattan schist.

Scully’s modesty makes me think back to Rose Hill Gymnasium on that rainy day in 2000. Michael T. Gillan, the dean of Fordham’s College of Liberal Studies, presented Scully with an honorary doctorate of human letters. With just two Latin words Gillan defined what makes Scully Scully: eloquentia perfecta. The literal translation is “perfect speech,” but the words connote communication of the highest order.

The concept emerged from the rhetorical studies of the ancient Greeks, grew through Renaissance humanism and was codified in Ratio Studiorum, the 1599 document that standardized the Jesuit teaching tradition. All Fordham freshmen must take Eloquentia Perfecta, a seminar course taught by the school’s most accomplished faculty. Eloquentia perfecta is the mastery of written and spoken expression guided by consistent principles. One of its core principles is humility. The speaker begins not with himself but with an understanding of the needs and concerns of his audience.

“Hello. I’ve meant to thank you.”

This is how Scully greets me. The unmistakable honey-dipped voice of the Irish tenor is lyrical as ever at 88. He walks into a suite on the press box level looking like a red-crested bluebird on the first day of spring, the famous thatch of red hair topping a suit jacket, shirt and tie in pleasing complements of blue. As always, he is impeccably dressed. He is sucking on a Jolly Rancher, a workplace habit he picked up years ago when he found a huge bowl of the candies in his Colorado hotel room. Every third out of a broadcast Scully pops one into his mouth “just to keep the pipes a little fluid” and then removes it when the game resumes.

• SI VAULT: The Transistor Kid: How Vin Scully became L.A.'s voice

He brings up an award presentation I made more than a year ago at the annual dinner of the New York chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America. The award honored Scully, Sandy Koufax and Bob Hendley on the 50th anniversary of a flawless night of baseball at Dodger Stadium: Koufax threw a perfect game, Hendley threw a one-hitter for the Cubs, and Scully called the broadcaster’s equivalent of a perfect game.

More than a half century later, Scully’s words from that game still float melodically, a conflation of Dylan Thomas and Bob Dylan that plays in your head like a favorite tune:

“Two and two to Harvey Kuenn.... One strike away....”

I had forgotten about the dinner. Scully, who rarely travels long distances, did not attend. Yet here he was, not just reminding me of it but also thanking me. “You had some very lovely words to say,” he told me.

I remind Vin about the home opener this year, when Koufax was among many former Dodgers greats who greeted him in a pregame ceremony on the mound.”

“I thought, Oh, wow. That’s nice,” he says. “Sandy has always been one of my favorites. Of all the players on the mound, he and I threw our arms around each other.”

Just then something magical happens.

I see it in his eyes. Vin is about to go on a trip. It’s the kind of trip that is heaven for a baseball fan: Vin is about to tell a story. For a listener, it’s like Vin inviting you to ride with him in a mid-century convertible, sun on your arms, breeze on your face, worries left at the curb. Destination? We’re good with wherever Vin wants to take us.

“Because, oh, I’m sure I’m the only person alive who saw Sandy when he tried out.”

And we’re off....

“Ebbets Field. We had played a game on kind of a gray day. Not a lovely day. And I was single, and the game was over early. I had nowhere to go, and somebody said, ‘They’re going to try out a lefthander.’ So I thought, Well, I’ll go take a look, and went down to the clubhouse. I looked over and my first thought was, He can’t be much of a player. The reason was he had a full body tan. Not what you call a truck driver’s tan, you know? Full body.

“But I did notice his back, which was unusual. Unusually broad. So I thought, I’ll go watch him, you know? And I had played ball at Fordham, so I saw some kids that could throw really hard and all of that. He threw hard and bounced some curveballs and ... nice, but you know, I never thought, Wow, you’re unbelievable. Nothing like that at all. So what a scout I am.”

It’s classic Vin. He never speeds when he drives. He takes his time. He stops to note details, such as the weather and the expanse of a teenage Koufax’s back. The use of the word “so” to link his sentences, where most people use the sloppier “and,” is warm and friendly. It is one of his trademarks. He includes himself in the story, but only as a self-deprecating observer.

“His timing is impeccable,” Monday says. “He’s never in a rush. It’s like the game waits for him. We have a little joke among us. When Vin starts one of his stories, the batter is going to hit three foul balls in row, and he’ll have plenty of time to get it in. When the rest of us start one, the next pitch is a ground ball double play to end the inning.”

Jan. 22, 1958, was an unusually warm winter day in New York. Sometime after 6 p.m., a handful of men climbed on a freight car at the Sunnyside rail yards in Long Island City in order to access a second-floor window of the Delmonico International Corporation’s five-story warehouse on Orchard Street. The men loaded 400 cartons onto wooden skids and broke four locks to get the merchandise to the ground floor loading platform, where a truck waited for them. The loss was noticed the next morning. Police questioned more than 50 possible witnesses but learned nothing.

What made the heist especially intriguing was that the thieves left untouched thousands of dollars worth of electronic equipment. They targeted only cartons of one particular item. The New York Times broke the news with this headline above a story on page 17: 4,000 TINY RADIOS STOLEN IN QUEENS; BURGLARS MOVE $160,000 CARGO FROM BUILDING AT BUSY RAIL FREIGHT SPOT.

The target: the TR-63 transistor radio by Sony.

Sony was a new name in the U.S. market. Just months before, it had introduced the TR-63 and selected Delmonico as its sole U.S. distributor. The TR-63 wasn’t the first transistor radio, but Sony’s model was groundbreaking for its small size. The publicity given to the heist, complete with a description of these tiny $39.95 radios in “green, red, black and lemon,” and especially because of the discerning eye of the burglars, caused a consumer sensation. One year later the U.S. market would be flooded with six million transistor radios made in Japan.

On the same day the thieves hit the Delmonico warehouse, three men walked onto the field of the cavernous Los Angeles Coliseum for a publicity event. Ed Davies, wearing a suit, and Morris DeConinck, sporting a fedora, both from the Del E. Webb Construction Company, stood behind a surveyor’s theodolite in one corner of the stadium’s field. Exactly 90 feet to their right, Michael Auria, another Webb employee, drove a stake in the ground. Shutters clicked. The men were laying out the baseball field for the new home of the Dodgers, who with the Giants had bolted New York City to bring major league baseball to California. Auria’s stake marked the site of first base.

Only five days earlier the Coliseum Commission had granted Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley permission for his team to play in the stadium while its new home in Chavez Ravine was being built. The photo made obvious one of the many oddities of the Coliseum as a baseball venue: It was huge. Behind the Webb employees arose 79 rows of seats, reaching 106 feet above field level. One day Dodgers outfielder Duke Snider would try to heave a baseball out of the Coliseum. He could only reach row 60. He also hurt his arm in the attempt, which prompted manager Walter Alston to fine him $250.

“In the far reaches of the vast arena ... the game resembled a pantomime,” Al Wolf would write in the Los Angeles Times after the 1958 home opener. “You couldn’t follow the ball, but the actions of the players told you what was happening.”

Jan. 22, 1958—the day the transistor radio became a hot consumer item and the day the Coliseum became a baseball stadium—was the day Vin Scully became a Los Angeles icon. A fan base new to major league baseball needed help not just learning the nuances of the game but also simply following the action from hundreds of feet away. The portable transistor radio had arrived just in time. The voice coming through that punched aluminum speaker grill would be both their teacher and friend.

It nearly wasn’t Scully. KMPC, the Dodgers’ radio station, wanted to hire its own announcers rather than inherit Scully and Doggett. O’Malley insisted the two remain.

O’Malley, in the name of capitalism, created another force that contributed to the cultural phenomenon of Scully. In Brooklyn the owner had televised virtually every Dodgers home game from 1947 through ’57. But in January of ’58, O’Malley told SI that “subscription TV will offer a solution to the problems that are plaguing many major sports.” The previous year he had entered into a relationship with a pay television company called Skiatron. Once in L.A., O’Malley no longer wanted to give away his product to viewers (even if technological and political hurdles would keep pay TV years away from being a viable option).

From 1958 to ’68, with only a rare exception here or there, Dodgers fans in Los Angeles could see their team on television only in the nine to 11 annual games the team played in San Francisco. O’Malley blocked the national Game of the Week from the L.A. market, even when the Dodgers were on the road. Virtually the only way to “see” the Dodgers play was to hear Scully describe it—even if you were in the Coliseum. California’s booming car culture, its beautiful weather that encouraged a mobile citizenry and the early local start times for most road games made Scully’s voice ubiquitous.

After just two years in Los Angeles, the Dodgers left KMPC for KFI and a sponsorship deal with Union Oil and American Tobacco Company that paid the club $1 million annually, the game’s second biggest local media package, even with virtually no television income, behind only the Yankees. Scully was the driving force of the revenue. By 1964 the Dodgers were paying Scully more than most of their players—$50,000, which was more than three times the average player salary and almost half the earnings of Willie Mays, baseball’s highest paid player at $105,000.

“I had played six years in the major leagues,” says Monday, who grew up in Santa Monica and broke in with the Athletics in the American League. “It wasn’t until my seventh year, when I was with the Cubs and we played the Dodgers, that my own mother finally thought of me as a major leaguer. Because it wasn’t until then that she heard Vin Scully say my name during a broadcast.”

Circumstances created an ideal audience for Scully. By tone, wordsmithing and sheer talent, Scully turned that audience into generations of votaries. He became not only a Southern California star but also a national treasure, branching out to call 25 World Series on radio and television when baseball was king. (In 1953, at age 25, he was the youngest ever to call the Series; in 1955 he called the first one televised in color; and in 1986 he called the highest-rated game in history, the Mets’ Game 7 win over the Red Sox.) He was the lead announcer for CBS in the 1970s on football, golf and tennis; the lead announcer for NBC on baseball in the 1980s; and even a game-show host (It Takes Two) and afternoon talk show host (The Vin Scully Show) in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The man who called his first event, a 1949 Boston University–Maryland football game, from the roof of Fenway Park armed with a microphone, 50 yards of cable and a 60-watt bulb on a pole now can be heard worldwide by anyone with an Internet connection and an MLB.tv subscription (though, because of a cable carrier dispute, not in 70% of the Los Angeles viewing market).

“Many of the best announcers have some of the best qualities Vin may have,” says MLB Network’s Bob Costas. “The command of the English language, the terrific sense of drama, the ability to tell a story.... But it’s as if you had a golfer who was the best off the tee, the best with the long irons, the best with the short irons, the best short game and the best putting game.”

Time for another ride. Hop in. . . .

“We were in the back of the auditorium,” Vin says. He is driving us back to Fordham Prep in the early 1940s. “I remember I said, ‘Larry, when we get out of here, what do you want to do?’ And he said, ‘I’d love to be a big league ballplayer.’

“And I said, ‘I wonder what those odds are.’ And then I said, ‘Well, you know, I’d like to be big league broadcaster. I wonder what those odds are.’

“And then I said, ‘How about this one for a long shot: How about you play, I broadcast, you hit a home run?’ And we said, ‘The odds, no one would be able to calculate that!’ ”

Larry was his friend, Larry Miggins. A few years later, on May 13, 1952, playing for the Cardinals, Larry Miggins hit his first major league home run. It happened at Ebbets Field against the Dodgers. On the call that inning in the broadcast booth happened to be Larry’s buddy from Fordham Prep, sharing duties with Red Barber and Connie Desmond.

“Incredible, isn’t it?” Scully says. “I mean, really, absolutely incredible. And probably the toughest home run call that I ever had to call because I was a part of it. He hit the home run against Preacher Roe, I’m pretty sure. And I had to fight back tears. I called ‘home run,’ and then I just sat there with this big lump in my throat watching him run around the bases. I mean, how could that possibly happen?”

Scully has called roughly 9,000 big league games, from Brooklyn to Los Angeles to Canada to Australia and scores of places in between. He has called 20 no-hitters, three perfect games, 12 All-Star Games and almost half of all Dodgers games ever played—this for a franchise that was established in 1890. The home run by Miggins was and remains the closest Scully ever came to breaking down behind the microphone.

Scully was born in the Bronx. He and his mother, Irish-born Bridget Scully, moved a few miles away to a fifth-floor walk-up apartment in Washington Heights soon after his father, Vincent Aloysius, a traveling silk salesman, died when Vin was four. Scully’s life path opened with clarity when he was eight years old. He crawled underneath the family’s massive wooden radio console to hear broadcasts of college football games; he heard a crowd before he ever saw one. The sound, as he likes to tell it, washed over him like water from a showerhead. He was hooked. When one day Sister Virginia Maria of the Sisters of Charity at the Incarnation School assigned her grammar class to write an essay on what they wanted to be when they grew up, Scully wrote enthusiastically of his dream to be a sports announcer.

“So now, when I’m in the booth, Kirk Gibson hits a home run and the place goes bananas,” he says. “I showed up, I sit there, and for that little moment I’m eight years old again.”

Says Costas, “He never shouts, but he has a way within a range that he can capture the excitement. If you listen to the [1988 World Series] Gibson home run.... ‘In a year that has been so improbable...’ he’s letting the crowd carry Gibson around the bases, but then he has a voice that has a tenor quality that cuts through the crowd.”

Most every other great announcer is framed by singular calls—and Scully, from the 1955 Dodgers to Koufax to Aaron to Buckner to Gibson, has a plethora of them. Such a narrow view, however, sells short his greatness. Like listening to all of Astral Weeks, not just one track, Scully is best appreciated by the expanse of his craft.

“What he truly excels at,” Costas says, “is framing moments like that and getting in all the particulars so the drama and anticipation builds. You don’t always get the payoff, but he always sets the stage. Other announcers have great calls of special moments. What he’s incredibly good at is leading up to those moments—all the surrounding details and all the little brushstrokes to go with the broad strokes.”

Here is more of what sets Scully apart: his literate, cultured mind. Scully is a voracious reader with a fondness for Broadway musicals. He doesn’t watch baseball games when he’s not broadcasting them. “No, not at all,” he says. He has too many other interests.

He once quoted from the 1843 opera The Bohemian Girl after watching a high-bouncing ball on the hard turf of the Astrodome: “I dreamt that I dwelt in marble halls.” When he appeared with David Letterman in 1990 he quoted a line from Mame. He suggested a title if Hollywood wanted to turn the 1980s Pittsburgh drug trials into a movie: From Here to Immunity. Last week, during a game against the Padres, he offered a history on the evolution of beards throughout history that referenced Deuteronomy, Alexander the Great and Abraham Lincoln.

Barber, his mentor, majored in education and wanted to become an English professor. Lindsey Nelson taught English after he graduated from college. Mel Allen went to law school. Ernie Harwell wrote essays and popular music. Graham McNamee started out as an opera singer. When Scully calls his last game—either the Dodgers’ regular-season finale on Oct. 2 in San Francisco or, if they advance, a postseason game—we lose not just the pleasure of his company with baseball but also the last vestige of the very roots of baseball broadcasting, when Renaissance men brought erudition to our listening pleasure.

“I really like to do the research,” he says. “So, in a sense, that’s a little bit in that renaissance area, the research of the game. Plus, I’ve always been—even in grammar school—always afraid to fail. So I always studied, not to be the bright guy but just to make sure that the good sisters didn’t knock me sideways, you know?”

A story: At age 88, in preparing for his 67th home opener, Scully notices a player on the opposing Diamondbacks’ roster with the name Socrates Brito. The minute he sees the name, Scully thinks, Oh, I can’t let that go! Socrates Brito! Inspired in the way of a rookie broadcaster, Scully dives into his research. So when Brito comes to the plate, Scully tells the story of the imprisonment and death by hemlock of Socrates, the Greek philosopher. Good stuff, but eloquentia perfecta asks more:

“But what in the heck is hemlock?” Scully tells his listeners. “For those of you that care at all, it’s of the parsley family, and the juice from that little flower, that poisonous plant, that’s what took Socrates away.”

It’s a perfect example of a device Scully uses to inform without being pedantic. He engages listeners personally and politely with conditionals such as For those of you that care ... and In case you were wondering.... Immediately you do care and you do wonder.

Scully isn’t done with Socrates. In the ninth inning, Brito drives in a run with a triple to put Arizona ahead 3–1.

“Socrates Brito feeds the Dodgers the hemlock.”

Someone once asked Laurence Olivier what makes a great actor. Olivier responded, “The humility to prepare and the confidence to pull it off.” When Scully heard the quote, he embraced it as a most apt description of his own work. So I asked Scully, because he pulls it off with such friendliness, if he had a listener in mind when he broadcasts games.

“Yes. I think when I first started, I tried to make believe I was in the ballpark, sitting next to somebody and just talking,” he says. “And if you go to a ballgame and you sit there, you’re not going to talk pitches for three hours. You might say, ‘Wow, check out that girl over there walking up the aisle,’ or, ‘What do you think about who’s going to run for president?’ There’s a running conversation, not necessarily the game. So, that’s all part of what I’m trying to do—as if I’m talking to a friend, yes.”

So, we are getting closer.

Time for another ride. This time we’re going to the Polo Grounds. Oct. 3, 1951.

“First of all, Red Barber had said to me when I first started, ‘I don’t want you to get close to the players, because if you get too close to the players, it will change your descriptive powers. Suddenly you see your man make an error, and you’ll try to make up for it and it would become a twisted broadcast.’

“The one fellow I got close to, despite Red’s rulings, was Ralph Branca. And Ralph was going to marry after that game—the next week. And he and [his fiancée] Ann and I went around the world together, but that’s another story. But I was closer to them, and I had a couple of dates with Ann’s roommate, and so, we got closer.

“So when the ball was hit, there was a home run, and I instinctively looked down at the club box because my friend Ann was there. And I watched her very deliberately, carefully open up her purse, take out a handkerchief, close the purse, open the handkerchief and bring it up to her face. And I really felt sorry for her and for everybody.

“And then in those days, in order to get to the clubhouse, you had to walk all the way to centerfield, and you went up the stairs and went in the door. And then there were, like, three steps to go up to the next level. And there was my pal [Branca], sprawled on the steps, head down, arms extended. And I actually had to tiptoe over him. So, it was really tough.

“Anyway, it was deathly quiet and I thought, I can’t hang out here. So I went up into a trainer’s room, and there was Jackie [Robinson] and Pee Wee [Reese]. Just the two of them. Nobody else there. I walked over and didn’t say a word—just sat down in a chair and it was silent.

“And then Pee Wee said, ‘You know, Jack, the one thing I just don’t understand?’ And Jackie said, ‘What, Pee Wee?’ He said, ‘Why this game hasn’t driven me crazy.’”

The pitcher Branca relieved in that game to face Bobby Thomson with one out in the ninth inning was Don Newcombe, the same man who started the first major league game Scully ever broadcast, on April 18, 1950, at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. When the Dodgers feted Scully before the home opener this year, Newcombe was one of the greats to meet him on the mound.

There was a moment at the end of the ceremony when the former players retreated to give Scully his own space and his moment near home plate. Gazing up on the adoring Dodger Stadium, where he has worked 55 of his 67 years in the business, Scully stood alone with his thoughts.

“I looked at him,” Monday says, “and I saw a look I never saw before. It was emotional. He never lost it, but it was wistful.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson once said, “Nothing great was ever accomplished without enthusiasm.” I remind Vin of this, and then I tell him, “You can’t be this great for this long without enthusiasm. So, for Vin Scully, what are the points of enthusiasm?”

“Well, I guess the challenge to be prepared, number one,” he says. “As soon as I have a little breakfast, I’m on the computer checking rosters to make sure that in that dramatic moment [I know if] somebody comes into the game who wasn’t on the roster three days before. Again, the fear of failing.

“And then, there’s the one thing that to me is the most important, and that’s the crowd. The enthusiasm of the crowd is enough even on those days when I think, you know, I’d rather be home sitting under a tree and reading a book or something. I’ve been asked several times now already, ‘What would you miss the most when you retire?’ I said, ‘The crowd. The roar of the crowd.’”

Finally, it’s time for me to take Vin on a trip, to let him slip into the passenger side. We’re going back to Fordham. Rose Hill Gymnasium, May 20, 2000.

“Oh, boy,” Scully says. “What an honor that was, you know?”

Scully spoke for 19 minutes that day. It was as far as he ever pushed himself “out ahead of the game.”

By then death had made too frequent a habit of visiting his otherwise dreamy life. The toll included that loss of his father to pneumonia when Vin was four; of his first wife, Joan, at 35, from an accidental overdose of medication when he was 44; of his broadcast partner and close friend Don Drysdale, at 56, of a heart attack on the road when Vin was 65; of his son Michael, 33, in a helicopter crash when he was 66; and of Doggett, 80, another broadcast partner and close friend, when he was 69. Through the sorrow, as through the joy, what carried him was his faith. The kid from Church of the Incarnation has long been a parishioner of St. Jude the Apostle Catholic Church in Westlake Village, Calif.

His words without baseball are even more beautiful and much more personal. His commencement address is as much the heart of eloquentia perfecta as its original definition in 1599.

The world “will try very hard to clutter your lives and minds,” Scully told them, but the way forward was to simplify and clarify.

“Leave some pauses and some gaps so that you can do something spontaneously rather than just being led by the arm.”

“Don’t let the winds blow your dreams away ... or steal your faith in God.”

Drawing upon his own bouts of grief, “be a bobbed cork: When you are pushed down, bob up.”

“It is written that somewhere in every childhood a door will open, and there is a quick glimpse of the future. When my door opened, I saw a large radio on four legs in the living room of my parents’ home. Above all, don’t ever stop dreaming. Sometimes even your wildest dreams can come true.”

I ask him to imagine his younger self, Fordham class of ’49, sitting in the same gym, hearing the same words from someone else: “How do you think those ‘wildest dreams’ turned out for a young Vin Scully?”

“Oh, for me, absolutely right on the money,” he says. “I’m not only getting this job to do a sport that I love, but then God’s charity allowing me to do it for 67 years.... It’s overwhelming. I mean, I have a big debt to pay in heaven—I hope when I get there—because the Lord has been so gracious to me all my life.”

Emerson also wrote, “The only way to have a friend is to be one.” Because his voice reached so many, so far, so kindly and for so long, no one in baseball ever accrued more friends than Vin.