Why the Red Sox' 1986 World Series loss might not be all Bill Buckner's fault

The following is excerpted from LOSING ISN’T EVERYTHING by Curt Menefee with Michael Arkush. Copyright © 2016 by Curt Menefee. Used by permission of Dey Street Books, a division of Harper Collins. All rights reserved.

“With the kids,” he said, “it’s all about St. Michael’s and how far we can go in the playoffs.”

Which is why it’s no surprise his favorite moment in baseball wasn’t when the Sox won the American League pennant in 1986 or when the Longhorns won the College World Series in 1983. His favorite moment was when his kids, the Crusaders, took their first of two straight state championships in 1997. They won three games on the final day. No small feat, for sure.

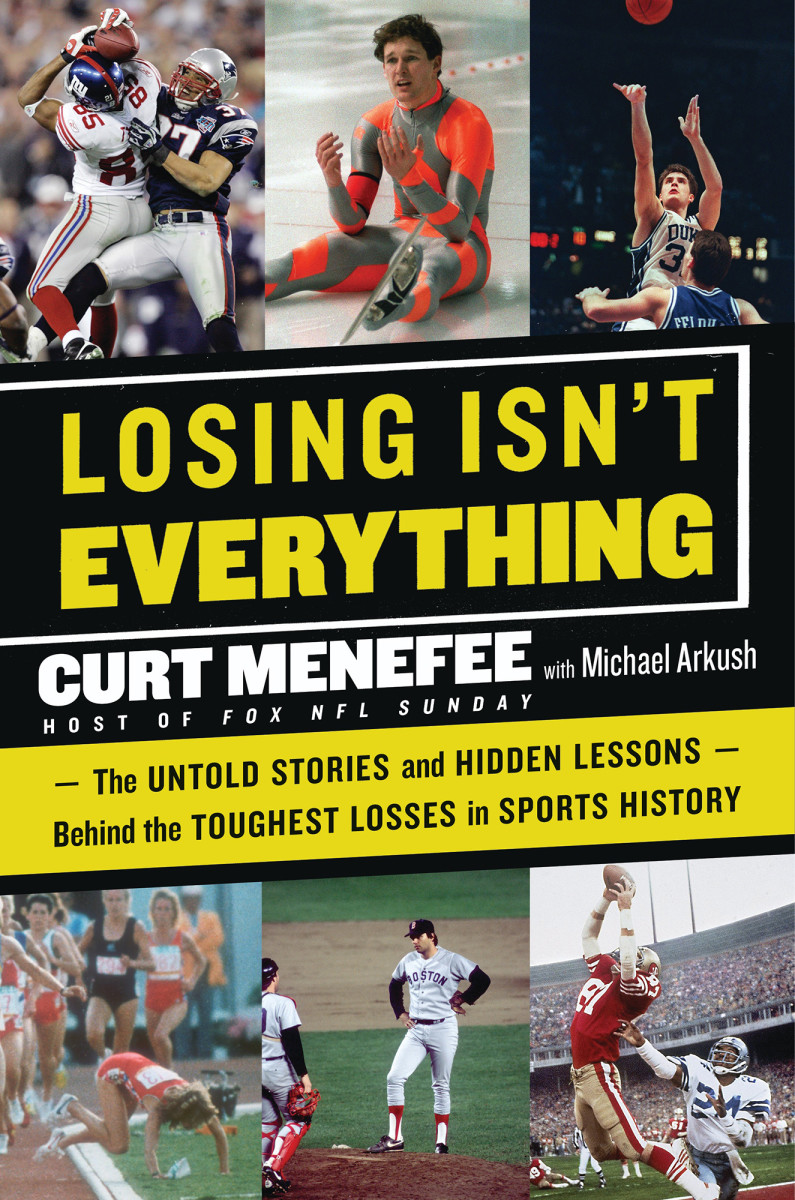

Losing Isn't Everything

by Curt Menefee

The untold stories and hidden lessons behind the toughest losses in sports history.

“It was awesome,” Calvin recalled. “I just sat there and watched them celebrate and dog-pile the mound. They’d never had a chance to do that.”

As for his best chance at a moment like that, on the game’s ultimate stage, he decided soon after the 1986 Series he couldn’t let himself feel bad about what he had missed. He felt he had no choice, really, if he hoped to be ready for the 1987 season, and any seasons after that.

“In order to perform,” he said, “you got to put walls up. You fail one day, you could succeed the next fifteen. But if you linger on what happened the one day you failed, you’re not going to be successful on the next fifteen. You shove it to the back of your brain and forget about it and move on.”

Spoken like a true reliever, and if you’re talking about one game during the long grind of the regular season, that’s exactly the approach you would want your closer to have. Except we’re not talking about 1 of 162 games. We’re talking about the game, Game 6 of the World Series, the game the fans in Boston, and all over New England, would never forget, so close their Sox had been to finally ending the curse.

To be fair, he had put up walls before, when he learned that baseball in the major leagues was a lot different from baseball in college, a business more than a game. Which first became clear fifteen months after the College World Series, when he made his big-league debut with the Mets on September 1, 1984. He started the second game of a doubleheader at Shea against the San Diego Padres. It was hardly the kind of opening start Calvin was hoping for—he gave up 8 hits and allowed 4 earned runs in only 3⅓ innings—but that didn’t mean he was prepared for the reaction he got when he left the mound. The fans booed.

“I was pitching behind Dwight [Gooden] that day, and I sucked; I’m not going to deny that,” he said, then added, “[But] you screw up one time and there are freakin’ boos.”

He also learned how easy it was for false information to make it into the newspapers. Two of his teammates, Keith Hernandez and Ron Darling, a pitcher, decided to spread a rumor one day that a player on the Mets was about to be traded, just to see what would happen. Within twenty-four hours, the “rumor,” as Calvin recalled, was in the New York Post.

The message couldn’t have been any clearer: I have to be careful in everything I do and say. We’re not in Austin anymore.

Building those walls wasn’t so hard to do back then, and by the time 1986 rolled around, he was an expert. It wasn’t so much the criticism he received for the Sox’ loss that caused him to build higher walls than before; it was how disappointed he was in himself.

“I’m harder on myself than I am on anybody else,” he said.

Though the fans did react horribly at times, on the road especially.

“’Eighty-six! You suck!” they yelled. “You lost the World Series.”

After 1986, those walls weren’t going to come down, not as long as he was in the majors and had to be on his guard. The problem is he’s still putting walls up, from time to time, and he hasn’t thrown a pitch in twenty-five years.

“You learn how to do it, and it becomes a natural thing to do in any situation,” he explained. “It doesn’t have to be baseball. It could be your kids, your friends, anything. Something happens and you automatically put up a wall.”

The price Calvin is paying at this stage of his life is massive, and he knows it’s because he never dealt with what took place in Game 6. He sees the price in his relationship with his wife, Debbie, who wants to have back the man she knew when they began dating in the minor leagues before it’s too late.

“I don’t remember that guy,” he said.

He sees it, too, in other relationships, the kind many of us take for granted.

“I miss being able to have a regular conversation with a stranger,” he said.

And he sees it in those moments when he reacts to something in a manner he doesn’t quite understand, asking himself later, “Why the hell did I do that?”

In some respects, the walls Calvin put up aren’t much different from the walls his father, Joe, put up between himself and the people closest to him, walls that never came down.

“I never saw the softer side of my dad,” Calvin explained. “One time, at the state championship, he shook my hand and said, ‘You did a good job.’ It was the first time he had ever done that.”

In 2005, while battling bile duct and prostate cancer, his father decided he didn’t want to suffer any longer, nor did he want those near him suffering on his behalf. So, one day, he pulled over to the side of the road and shot himself to death. Calvin understood. He said he would probably have done the same thing if he’d been in that position.

“We watched his mom, who was ninety-seven, wilt away in a bed,” Calvin said, “and he wasn’t going to be the kind to do that.”

Dealing with his father’s suicide added another complication to what he’s had to go through, which, as you can tell, is a lot.

The good news, though, is that he’s receiving help from a therapist he sees every week or two. He’s making progress. A few of the walls are starting to come down.

“My wife and I haven’t been very close lately, and the walls are the reason why,” he said. “I needed to break down and show that I’m trying to figure out things, to get inside myself. She’s been fantastic about it. You can’t do it alone.”

Remembering the 1986 World Series

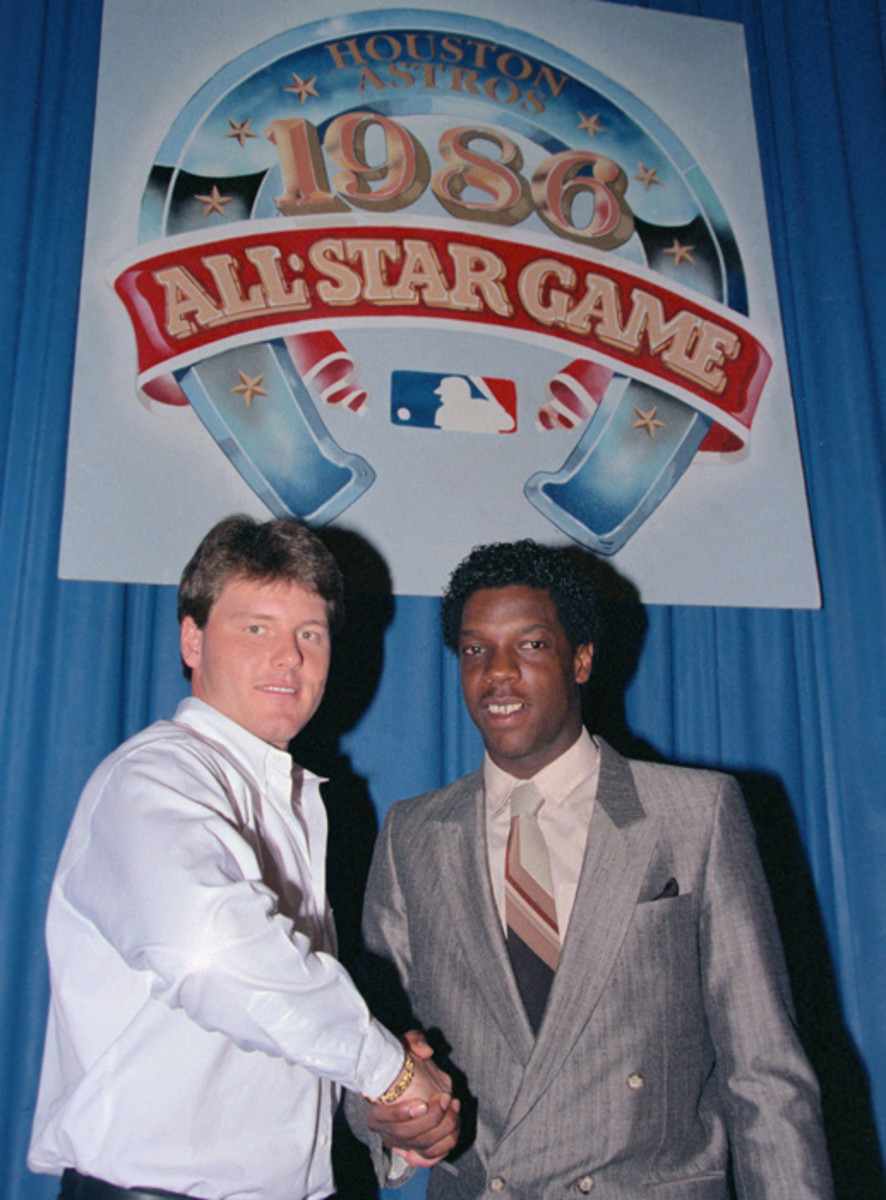

Roger Clemens and Dwight Gooden

This October marks the 25-year anniversary of the Mets' World Series victory over the Red Sox. Though the games are a quarter-century old, they remain some of the most memorable in baseball history. Here is a look back at those memorable eight days.In this photo, taken during All-Star weekend in Houston, American League starter Roger Clemens shakes hands with National League starter Dwight Gooden. The two would later lead their teams to the World Series.

Boston Red Sox

The Red Sox went 95-66 during the regular season and defeated the Angels in a memorable ALCS to advance to the World Series. Against California, Boston rallied from a 3-1 series deficit, including a dramatic comeback victory in Game 5 to avoid elimination.

New York Mets

The Mets cruised to a league-best 108-54 mark, winning the NL East by 21.5 games. In the NLCS, New York defeated Houston in six games, highlighted by a 16-inning victory in the clincher.

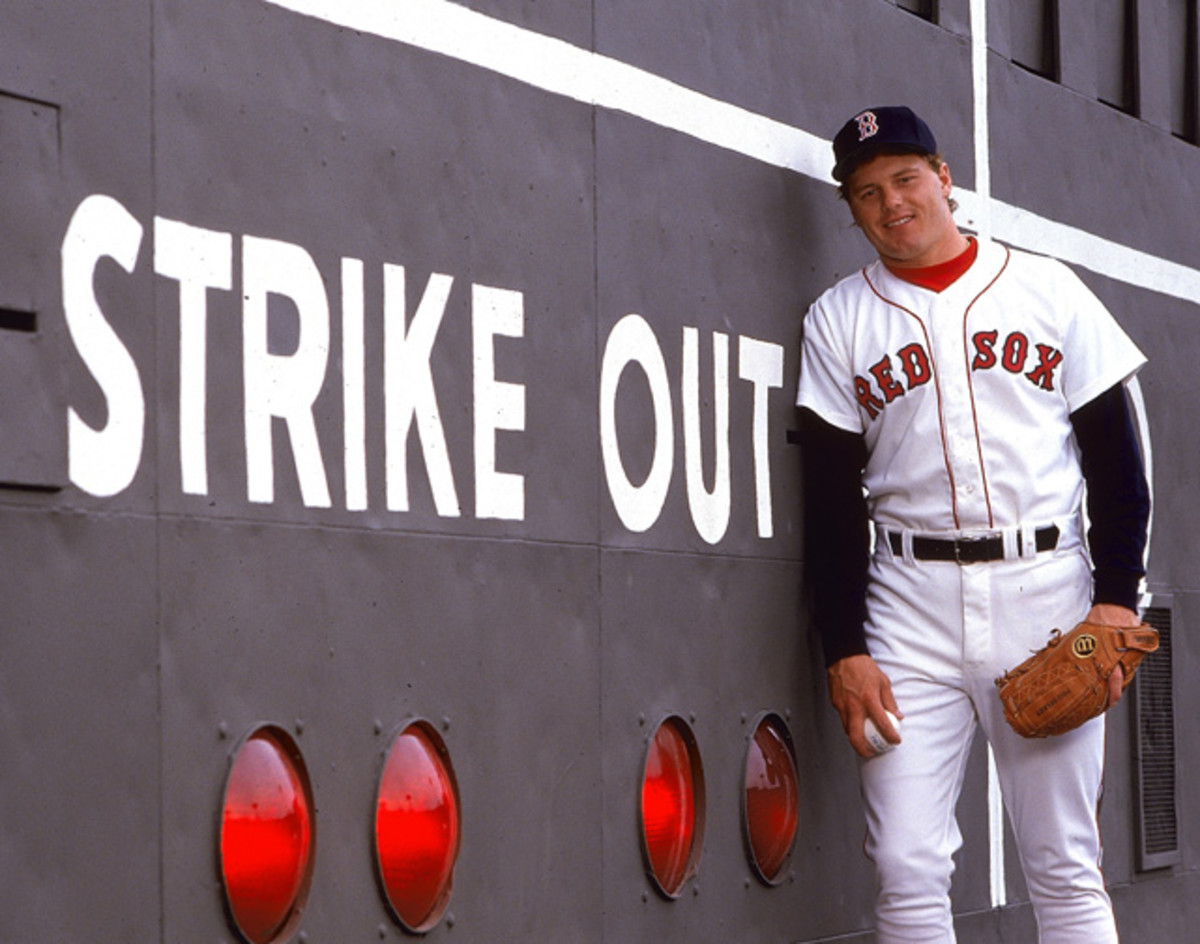

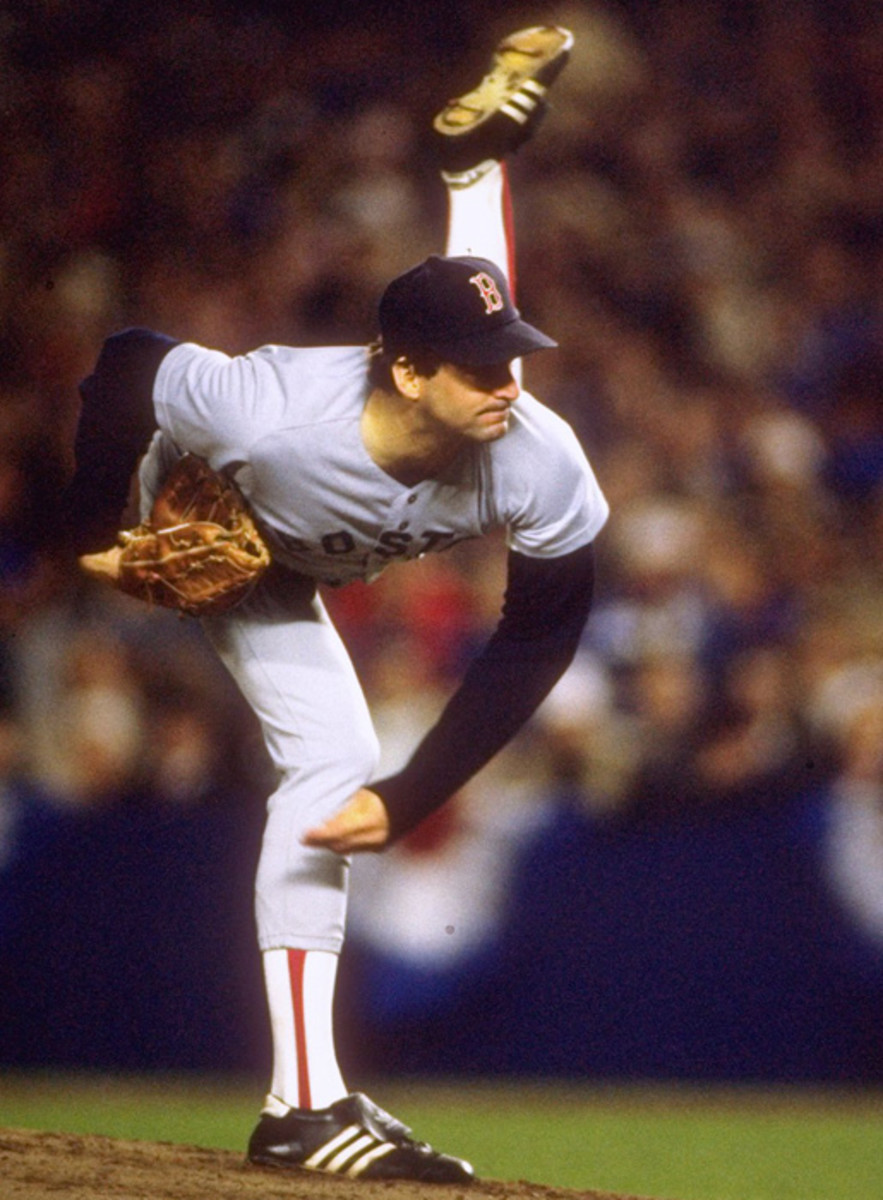

Roger Clemens

The Red Sox were led by 23-year-old Roger Clemens. The Texas native compiled a 24-4 record with a 2.48 ERA, which earned him both the Cy Young Award and American League MVP honors. He also became the first pitcher to strike out 20 batters in a game, in an early-season matchup against Seattle.

Dwight Gooden, Mike Tyson and Darryl Strawberry

With a balance of dynamic youngsters and established veterans, the Mets were one of the most popular teams in baseball. Its two youngest stars, Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden, were especially loved by New Yorkers. In this photo, Mike Tyson jokingly sticks a left jab to the face of Gooden.

Keith Hernandez and Wade Boggs

Two other notable players were Red Sox third baseman Wade Boggs and Mets first baseman Keith Hernandez. Boggs led all of baseball with a .357 average during the regular season while Hernandez batted .310 and won a Gold Glove. In this photo, the two shake hands before the start of the World Series.

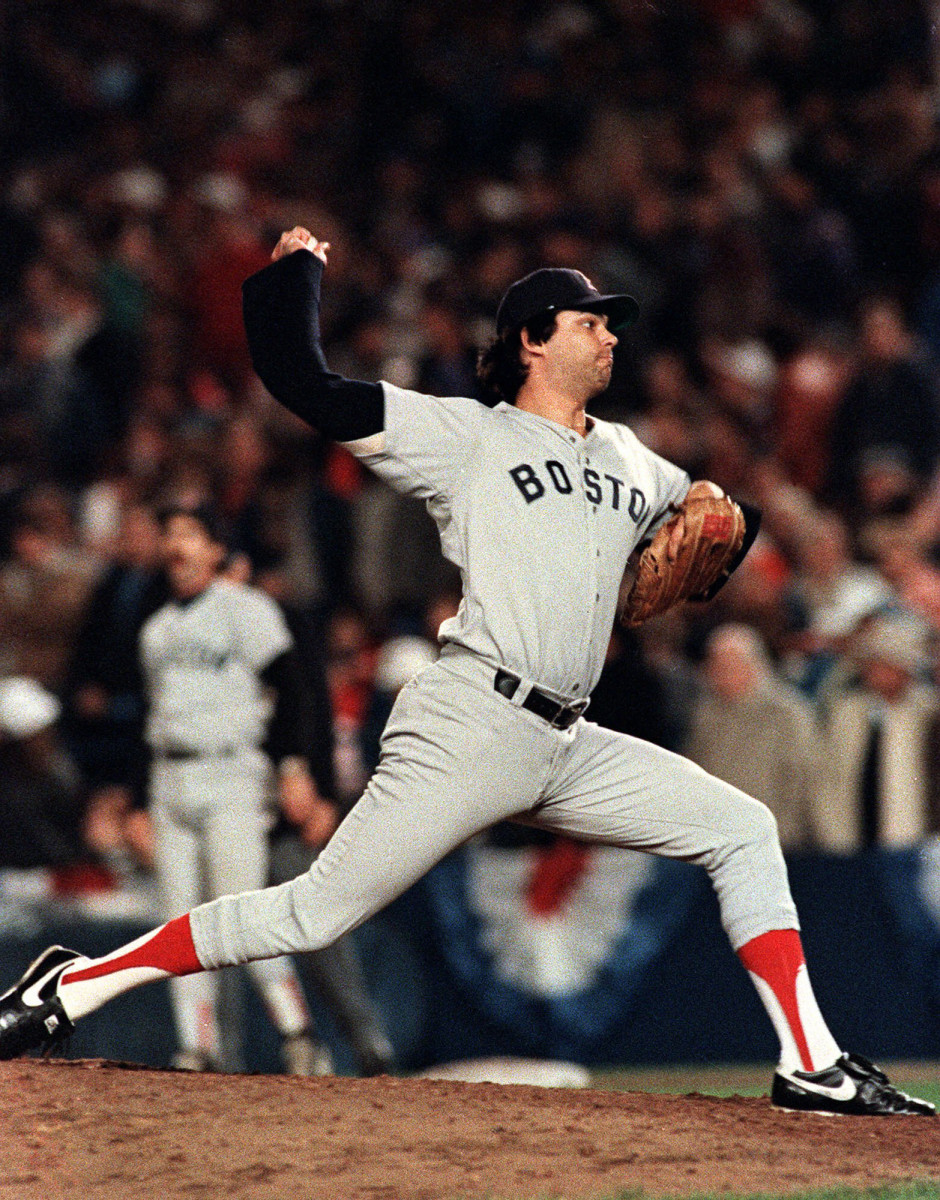

Bruce Hurst

In Game 1, Red Sox starter Bruce Hurst was masterful, pitching eight innings and giving up four hits and no runs. Mets starter Ron Darling was also strong, but gave up one unearned run that turned out to the difference in Boston's 1-0 victory.

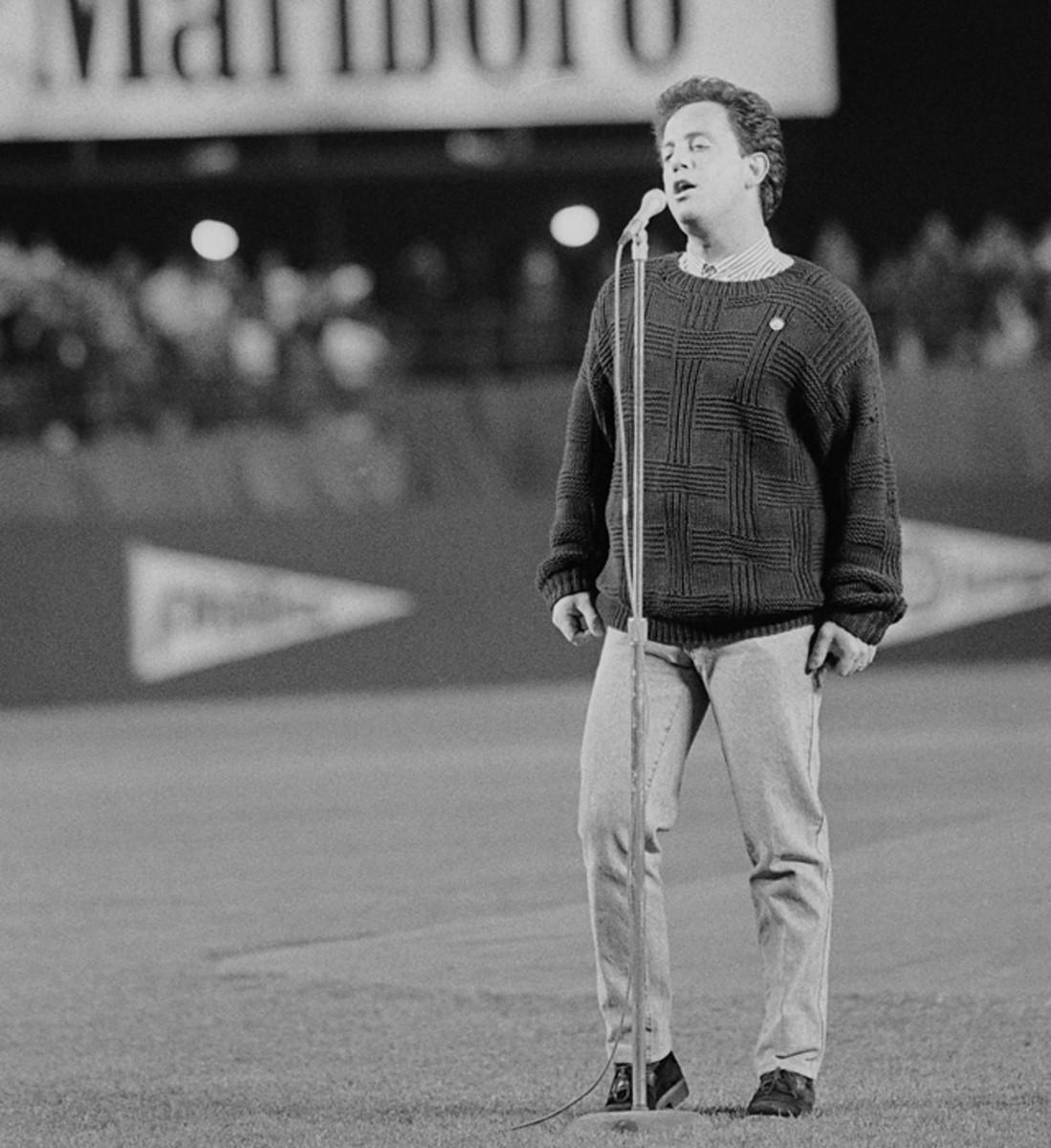

Billy Joel

New York native Billy Joel sings the national anthem before Game 2.

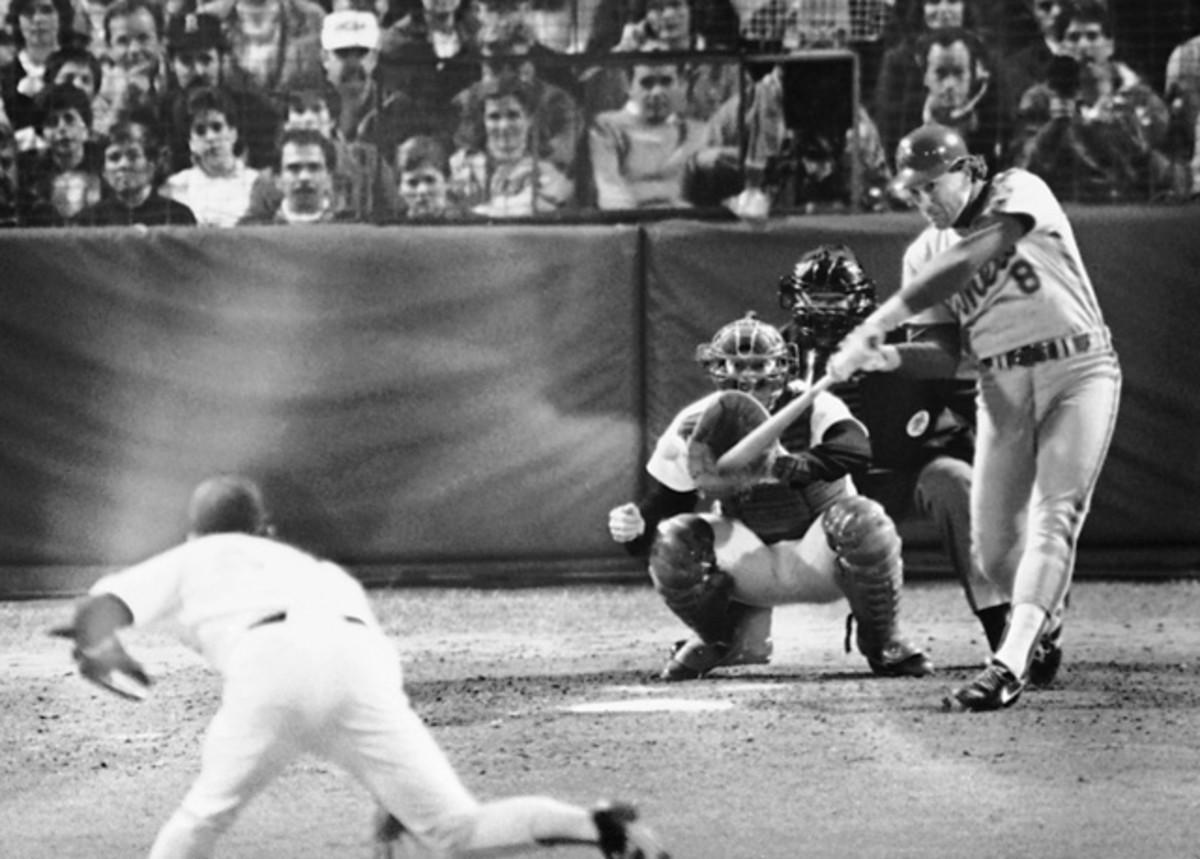

Lenny Dykstra

After losing to the Red Sox again in Game 2, the Mets responded in Game 3 at Fenway Park with a 7-1 victory. Lenny Dykstra (pictured here during the season) led off the game with a home run against Oil Can Boyd and collected four hits in the rout.

Gary Carter

In Game 4, Gary Carter homered twice as the Mets rolled 6-2 to even the series at two games apiece.

Jim Rice

Boston's Bruce Hurst was again outstanding in Game 5 at Fenway, going the distance in a 4-2 victory. Mets ace Dwight Gooden struggled early and was pulled after four innings and three earned runs. Jim Rice (pictured) had two hits and scored a run for Boston.

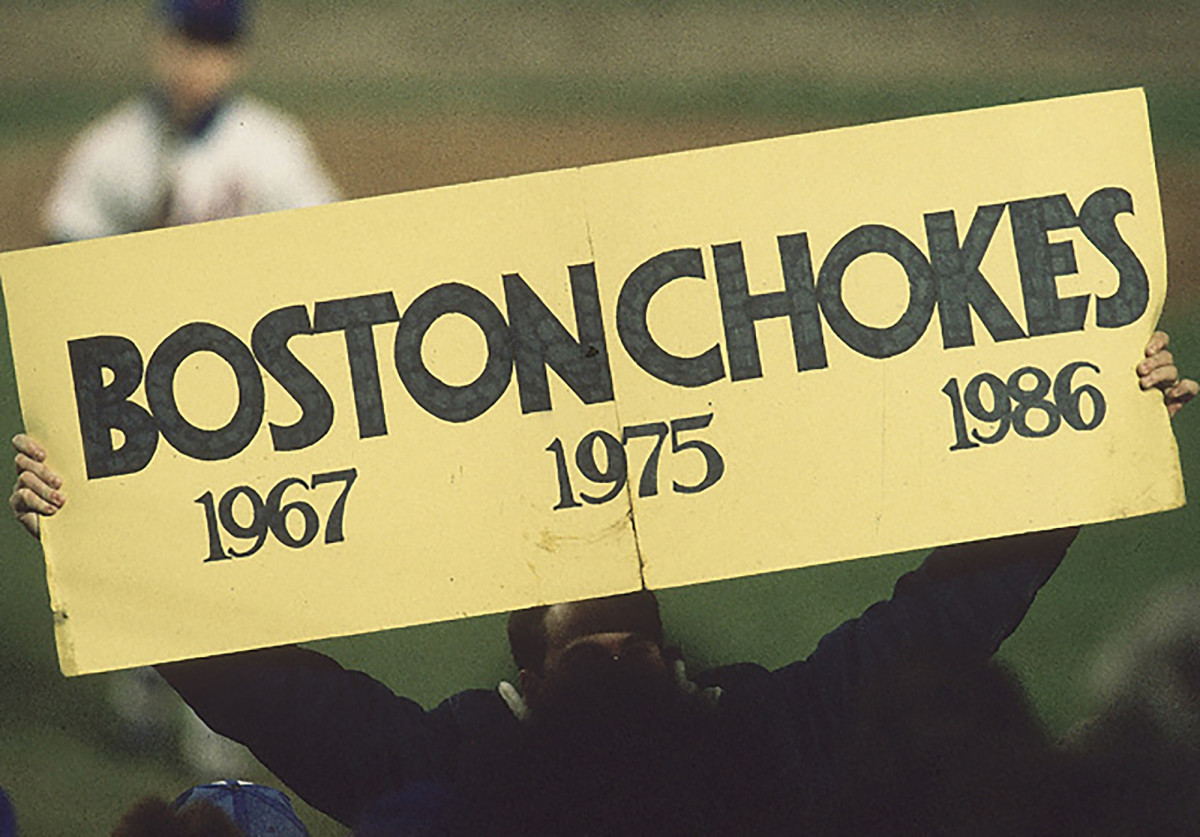

Mets Fans

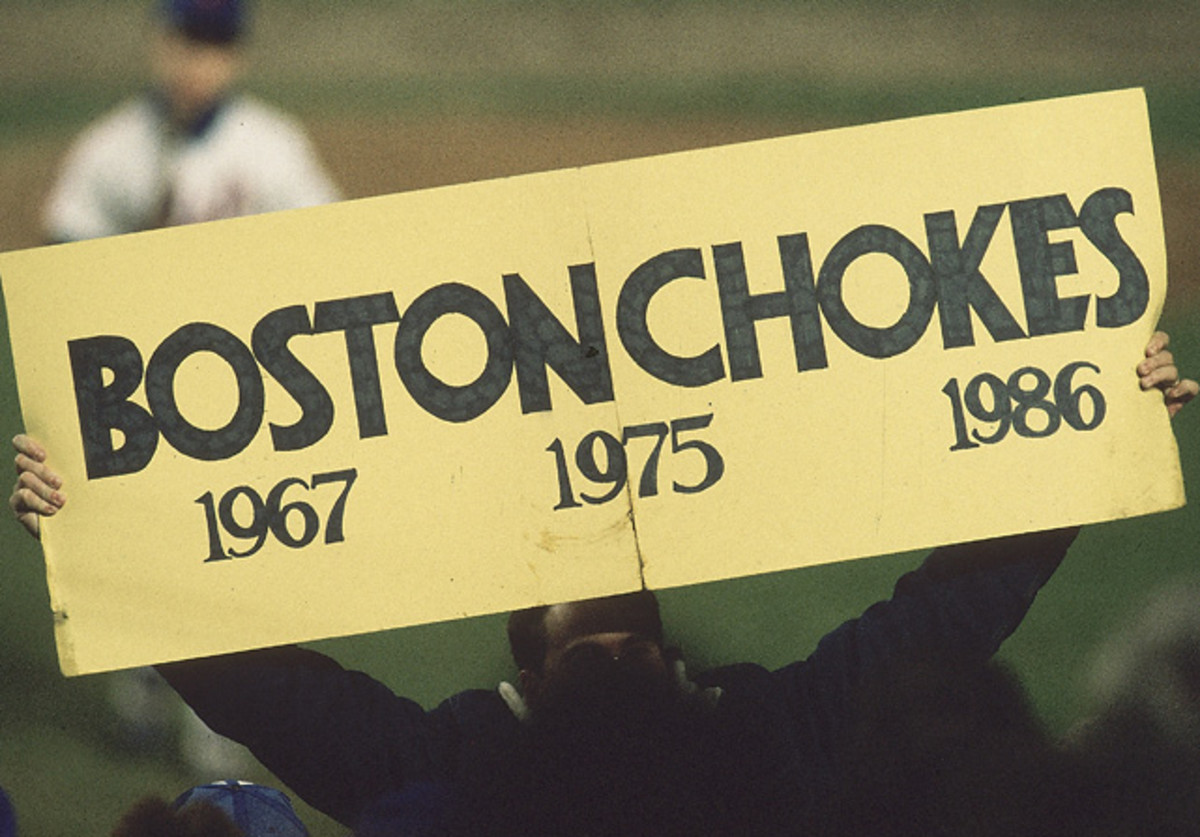

Going into Game 6, Boston fans hoped to wipe away nearly 70 years of heartbreak with a World Series victory. The fans at Shea Stadium were quick to remind the Red Sox faithful about their tortured history.

New York Mets

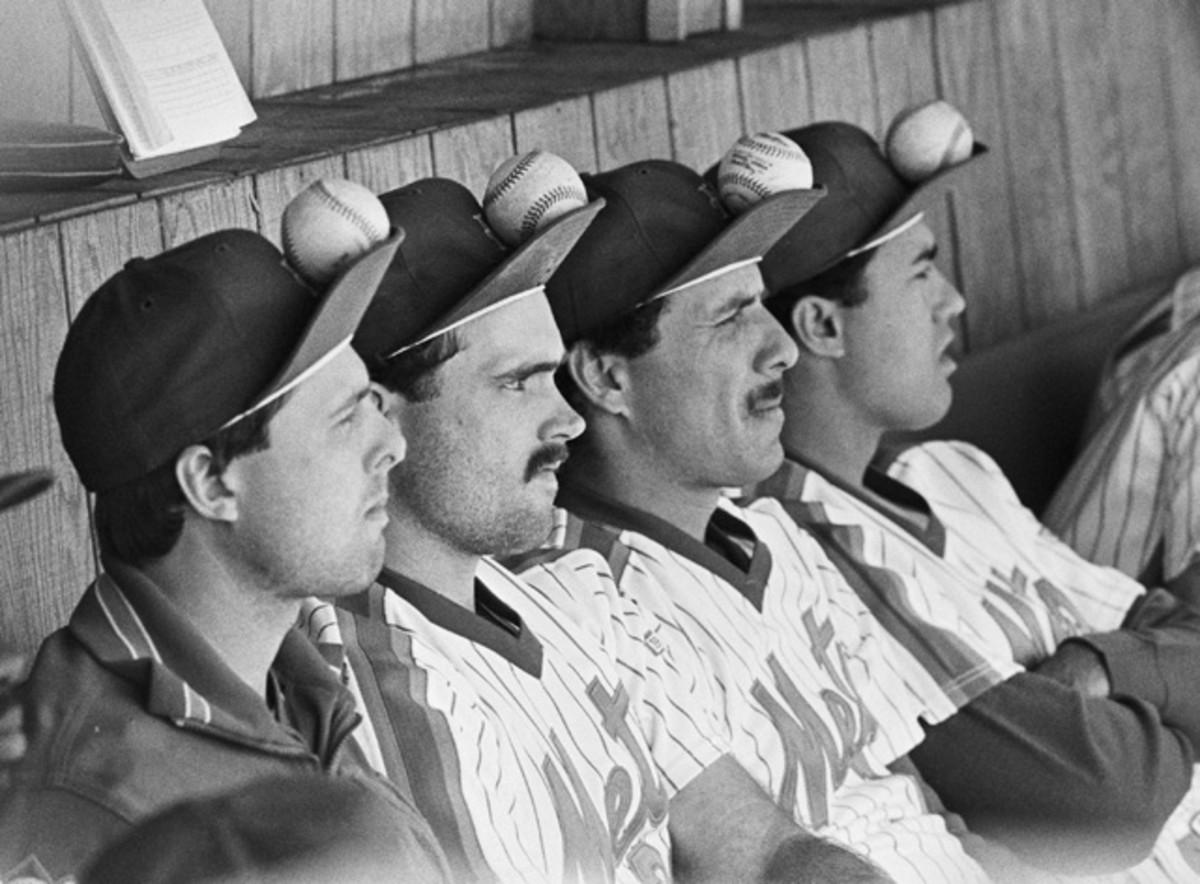

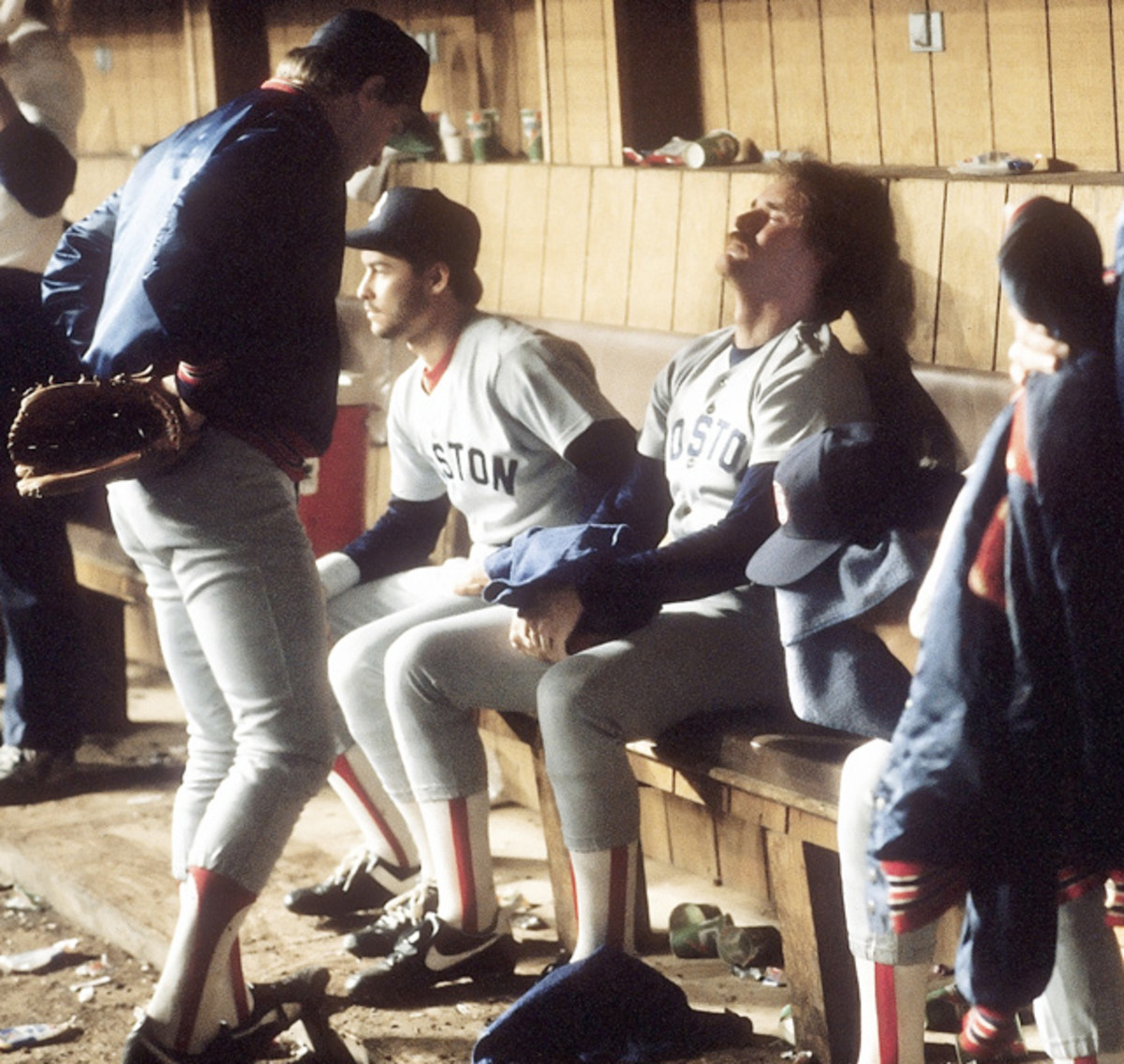

In Game 6, Boston had leads of 2-0 (in the fifth) and 3-2 (in the eighth) but the Mets, donning rally caps in the dugout, came back to tie it both times. The score was 3-3 in the 10th inning when Dave Henderson hit a solo home run and the Red Sox tacked on one more run for a 5-3 lead.

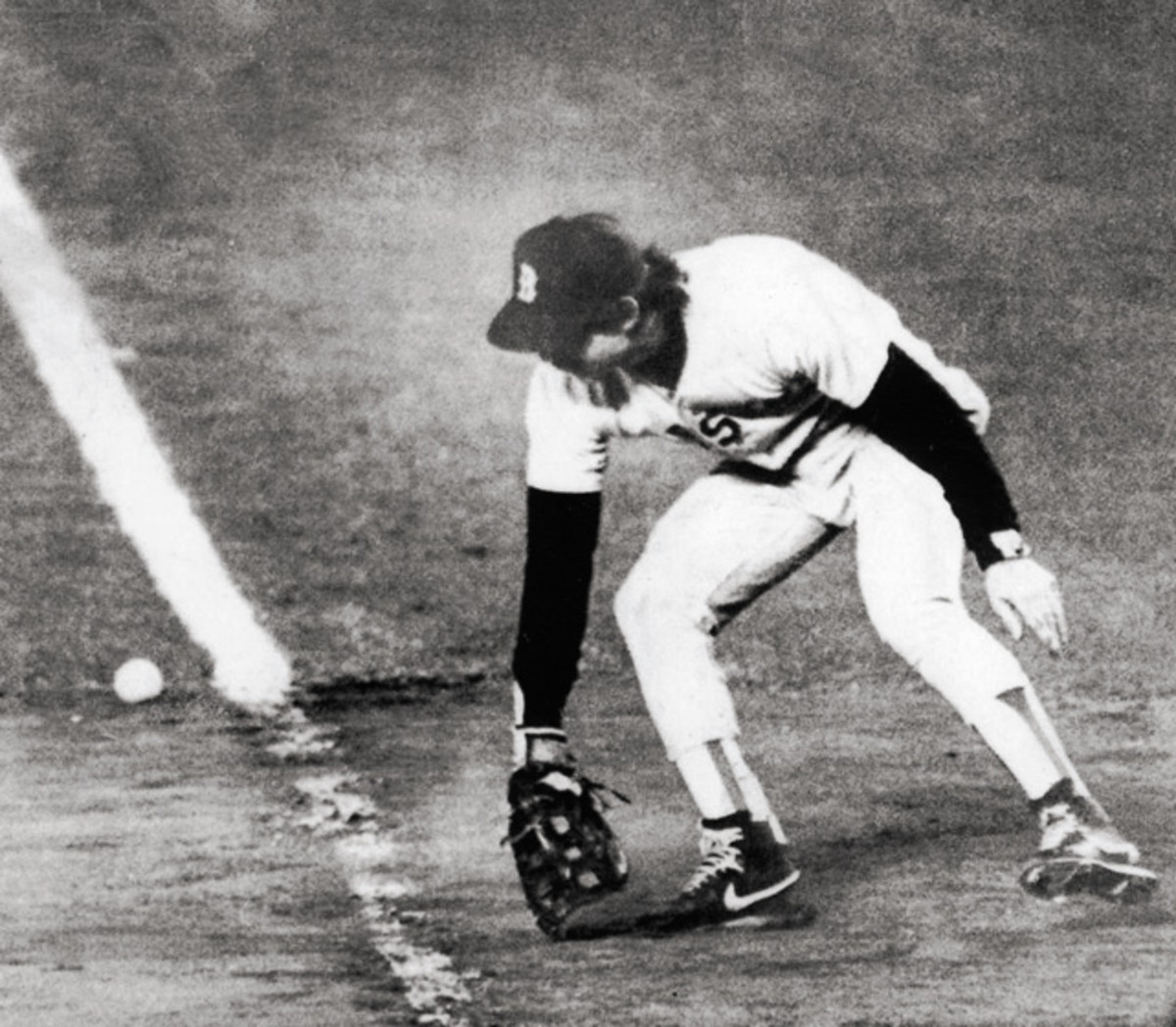

Bill Buckner

In the bottom of the 10th, Red Sox reliever Calvin Schiraldi retired the first two Mets batters before a combination of three singles and a wild pitch (the latter thrown by Schiraldi's replacement, Bob Stanley) led to two Mets runs. Then, with the game tied at 5-5 and Ray Knight at second, Mookie Wilson's routine ground ball to first went through Bill Buckner's legs, allowing Knight to score the winning run.

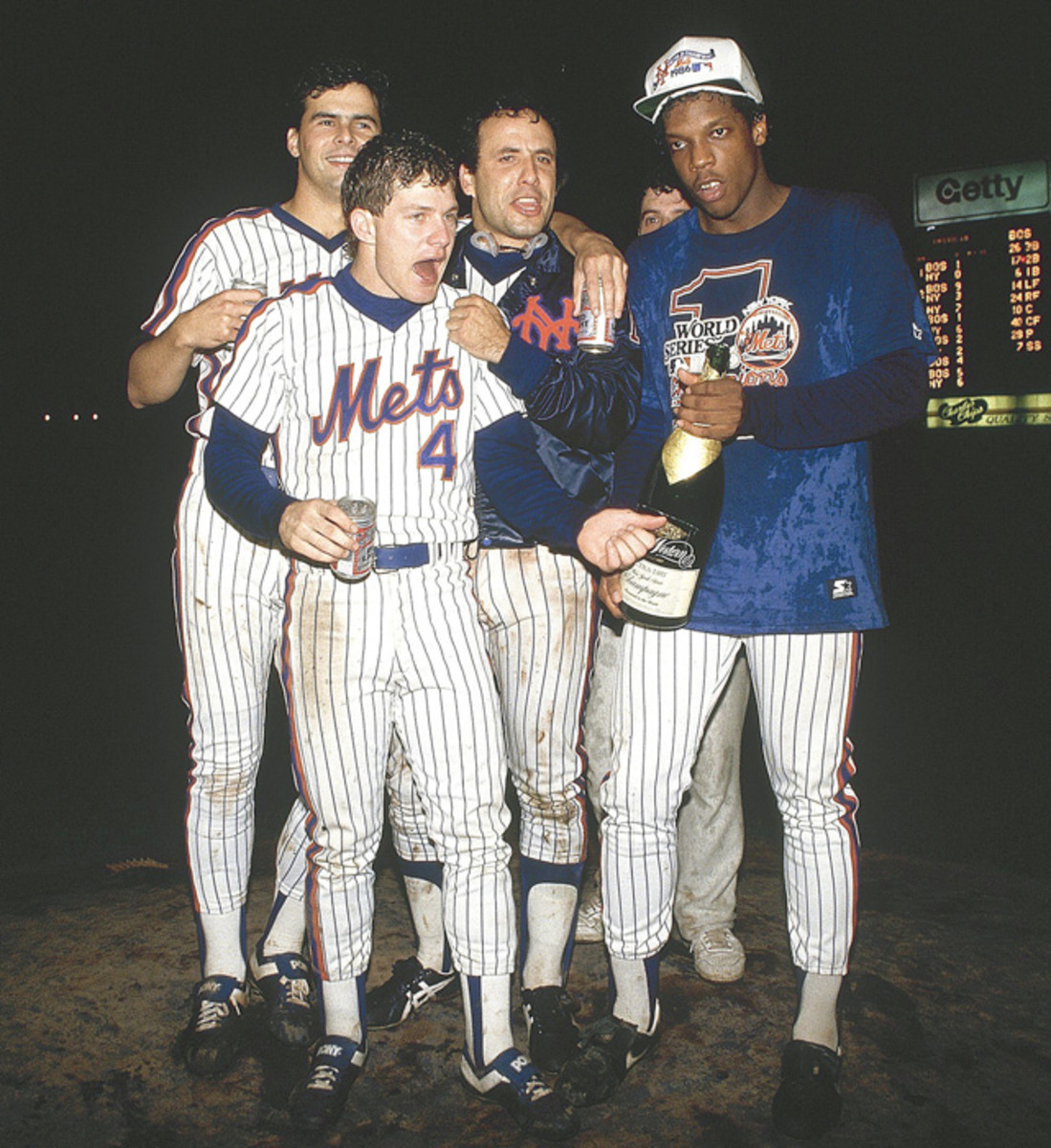

Gary Carter and Jesse Orosco

In Game 7, the Mets trailed 3-0 before scoring all of their runs in the sixth, seventh and eighth innings of an 8-5 victory. It was the franchise's first championship since 1969.

Lenny Dykstra, Rick Aguilera, Bob Ojeda and Dwight Gooden

Lenny Dykstra celebrates with Rick Aguilera, Bob Ojeda and Dwight Gooden after winning Game 7.

Wade Boggs

As the Mets celebrated, the impact of the loss is felt by Wade Boggs and the rest of the Red Sox.

Ray Knight

Third baseman Ray Knight, who was named World Series MVP, waves to crowds of New Yorkers during the championship parade.

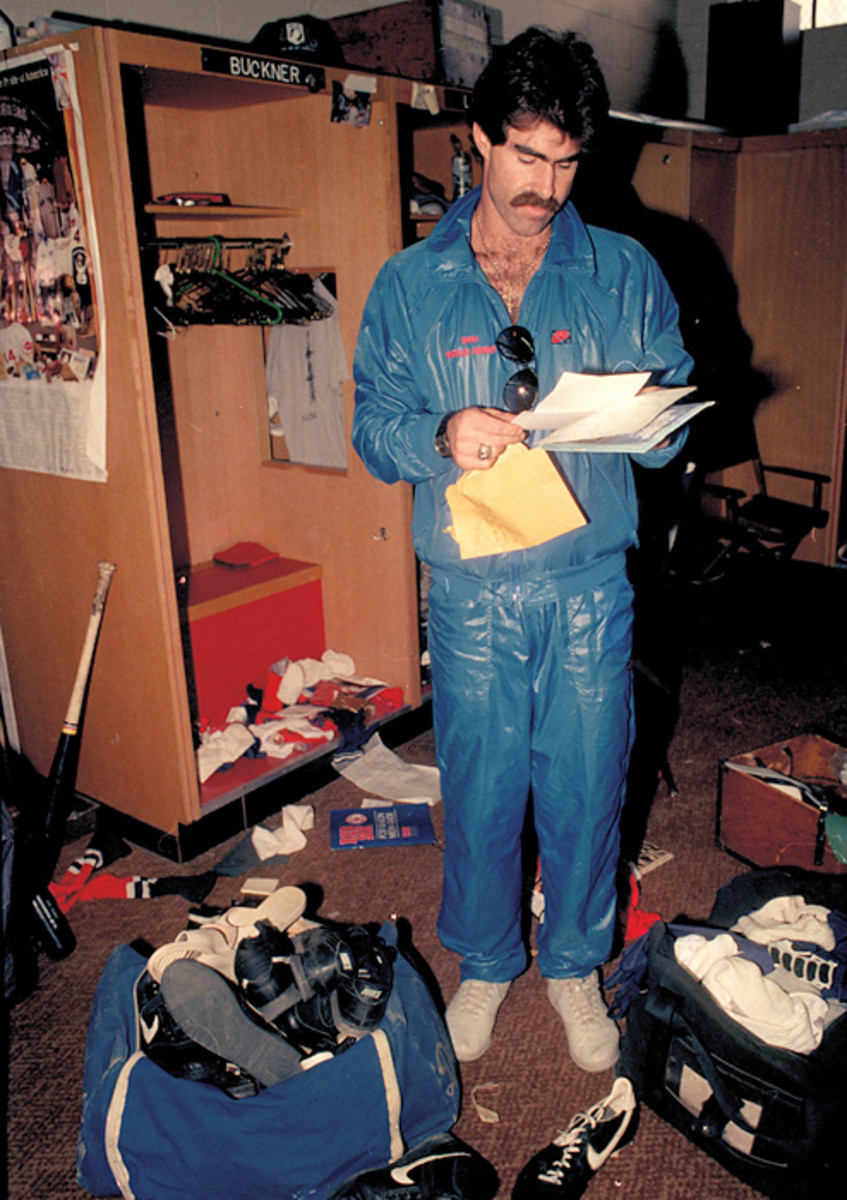

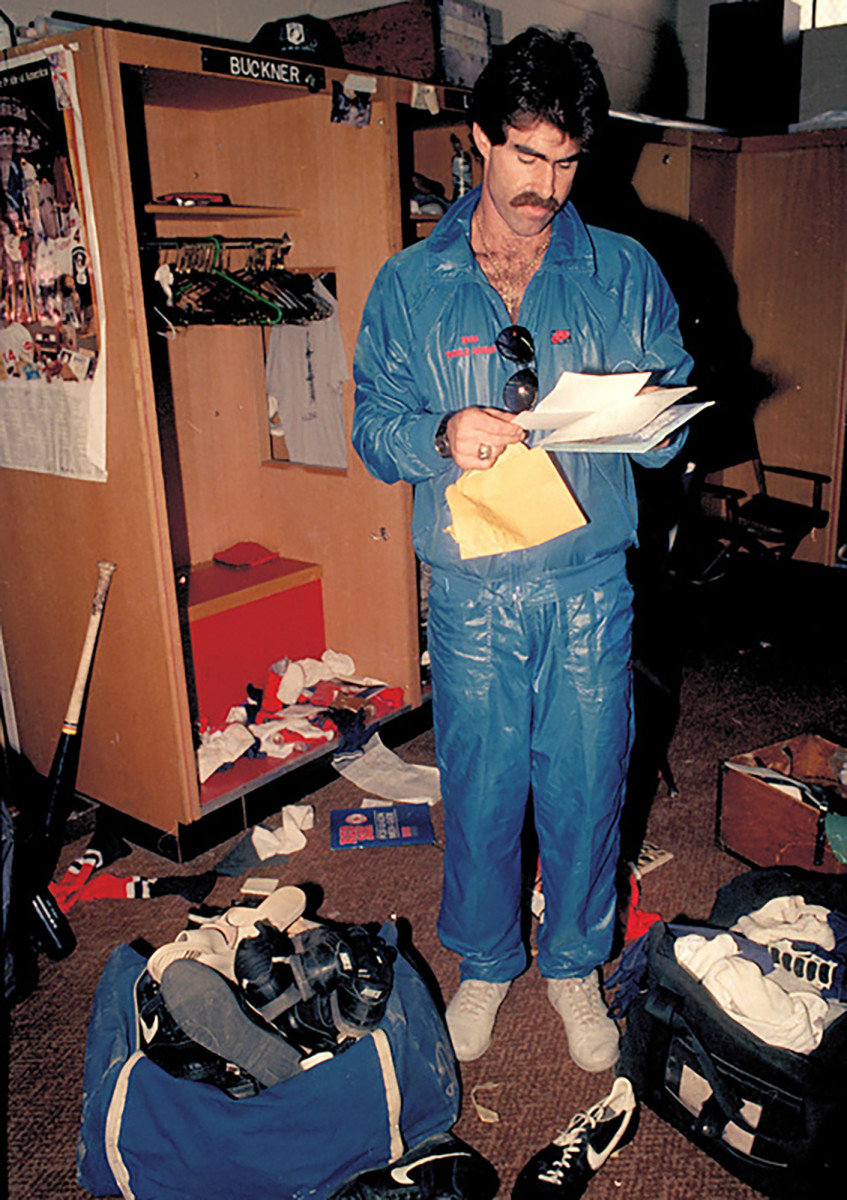

Bill Buckner

Bill Buckner reads some mail as he clears out his locker at Fenway Park one day after the Red Sox lost the World Series.

Some of the truths he has learned about himself haven’t been very pretty, but he vows to keep digging, no matter what else might turn up.

“It sucks,” he said. “I’m just waiting for the end of it. I want to be like I was before, when I was twenty-two or twenty-three.”

A topic that will no doubt come up is 1986. “We’re getting there,” Calvin said. “We still haven’t gotten there yet.” He knows 1986 might very well be the key to knocking the walls down for good.

“That’s what I’m hoping,” he said.

One thing that isn’t a mystery is why he has been able to relate so easily to the kids he coaches. It’s because being around them and helping them grow brings him back to his own past in the game that he still loves. Before he was booed, before he let a city, and himself, down.

“It’s still a game to them,” he explained. “I don’t make it life or death to them. I get pissed when they screw up, they know that, but it’s because I either haven’t taught them what I want them to know or they haven’t learned what I told them.”

His goal is to make sure his players learn from his mistakes.

“Mine were on a big stage,” he said. “I’m trying to make theirs as little [as possible] on a little stage.”

One can’t help but wonder, though, how different his life would have been if he’d gotten just one more out, instead of allowing those 3 straight hits in Game 6. Not only would the Red Sox have won it all, but perhaps he wouldn’t have built any more walls. Perhaps, a hero forever in Boston, he would have even torn down the ones he built before.

Calvin doesn’t see it that way. Of course, he would never have wished for his team to lose a World Series, especially in the manner the Sox lost, but he came to appreciate how it shaped him, in spite of the walls, and that could be a lesson for us all. Lose a lover, a job—lose anything of value—and as awful as it might feel at the time, you can’t imagine the person you’d be today if you hadn’t gone through the experience, if you hadn’t grown. In Calvin’s case, he wouldn’t change a thing about Game 6.

“That’s what made me who I am,” he explained.

Think about it: if he had gotten any of those three hitters out, he probably would not have spent the past twenty years at St. Michael’s, and that he can’t fathom.

“I think I’ve affected a lot more people this way,” he said, “than if we had won the World Series. I could have been a complete jackass.”

As tough as Calvin had it, though, two of his teammates had it worse: Stanley and, of course, Buckner. Nobody has suffered more ridicule for one specific play than Bill Buckner, in baseball or any other sport.

“He has taken a lot of shit that is not deserved,” Calvin said.

“People make errors.”

He’s just as upset at how Stanley was mistreated.

“That was brutal,” he said.

Does Calvin feel any guilt for what Buckner and Stanley have gone through? No, not really, although he quickly added: “If I had done my job, that would have never happened.”

He’s right, and when you think about it, he’s gotten off pretty easy compared with what Buckner has had to experience. Giving up those three hits had a lot more to do with the Red Sox losing than one botched play by the first baseman.

Yet the Buckner blunder, a single, more dramatic moment of ineptitude, is what people recall about Game 6 of the 1986 World Series. That’s how cruel history can be: those who lived it always at the mercy of those who remember it.

As for how Calvin feels about the city of Boston and Red Sox fans, he has nothing but good things to say. When he flew up there for a reunion several years ago, people couldn’t have been nicer.

Finally winning the World Series in 2004, 2007, and 2013 has certainly made it much easier for them to forgive.

Now if only he could forgive himself. The walls were supposed to protect him, but in the end, all they did was imprison him. It’s taken Calvin a long time, but he now realizes they must come down if he is to ever truly cope with that horrible night at Shea.

And again be the man his wife fell in love with.