Marvin Miller Didn't Want to Be a Hall of Famer. Now What?

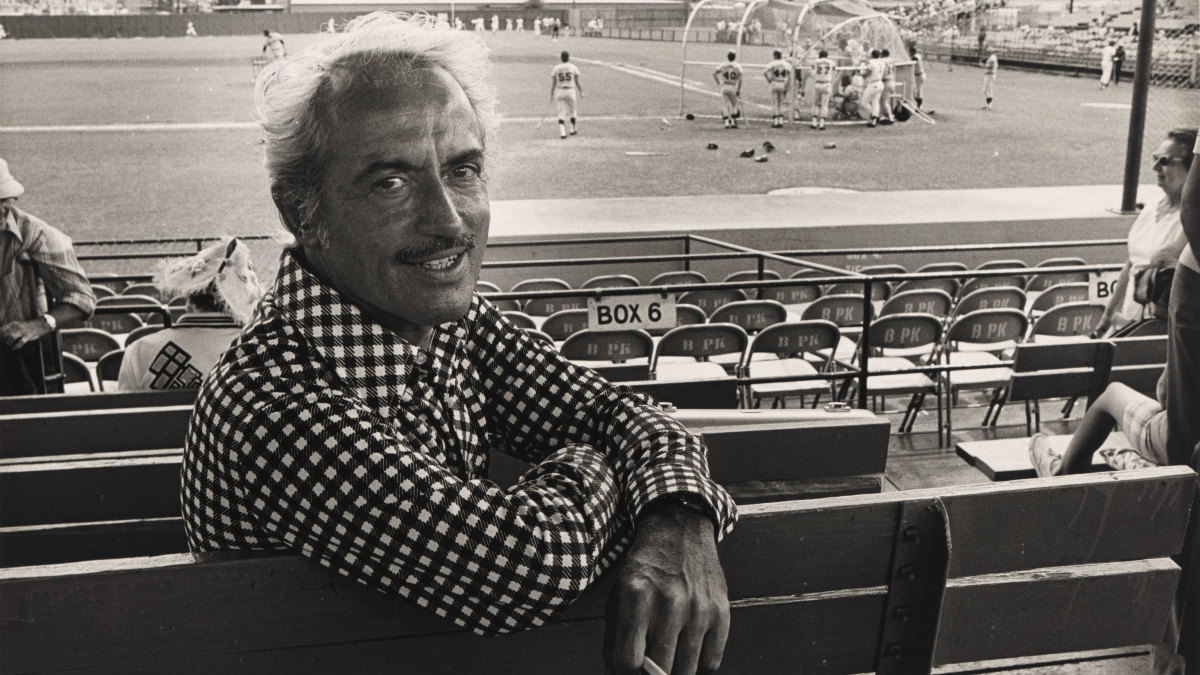

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Peter D. Miller, son of Marvin J. Miller. © Ray Fisher

In May 2008, Marvin Miller wrote a letter to the Baseball Writers’ Association of America:

“Paradoxically, I’m writing to thank you and your associates for your part in nominating me for Hall of Fame consideration, and, at the same time, to ask that you not do this again.”

Two and a half decades after he’d retired as executive director of the players’ union, Miller had just been passed over by the veterans committee for the third time. His letter went on:

“I find myself unwilling to contemplate one more rigged veterans committee whose members are handpicked to reach a particular outcome while offering the pretense of a democratic vote. It is an insult to baseball fans, historians, sports writers and especially to those baseball players who sacrificed and brought the game into the 21st century. At the age of 91, I can do without farce.”

There was more farce ahead. Against his wishes, Miller’s name was included on the ballot for both 2010 and 2011, unsuccessful both times. After his death in 2012, he was listed posthumously for 2014, 2018, and, finally, for 2020. That’s the end of the line—Miller was elected on that final one, announced last Sunday, and he’ll join the Hall’s class of 2020. Which leads to a question that baseball has previously not had much reason to concern itself with: What should the Hall of Fame do with someone who doesn’t want to be there?

For Miller, he wanted his answer to be the same in death as it was in life.

“All I can do is say what he said during his lifetime,” Miller’s son, Peter, told Sports Illustrated in November, when his father had been placed on the ballot. “Which is that he did not want to have his name placed in nomination, and in the unlikely event that he was ever voted in, he would not take part in it. And I checked with him periodically—in the years, months, weeks, up to his death, including two days before his death—to see if that was still his feeling, and what he would like me to do in that eventuality. He said, yes, that’s his feeling. So I’m bound to honor that.”

He shared via email when his father’s election was announced: “It doesn’t make any difference.”

He saw it not as an act of bitterness but as a basic principle. “For those given to speculating on motives,” he wrote, “I assure them that personal resentment had nothing to do with his decision not to take part in HoF procedures.” This was, Peter maintained, simply not what Miller wanted from his life or his work: “My father never sought personal fame.”

It’s easy to say that there is no reason to consider inductees’ personal desires. That holds if the Hall is meant to be only a record of the game’s history—part monument, part textbook, all honest and unemotional. (After all, the full title is National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, and the final two words may be the most crucial.) But the institution is full of personal desires. It’s built on them. A ballot is a record of personal desire; some are validated by statistics and film and information, some, not so much, but all are personal. The Hall is biased, because it could not exist otherwise. All of its debates—about home runs, about defense, about the character clause—are about individual desires and how they should be valued. It’s just that the desires in question are never those of the candidates.

That’s, of course, natural; there are few overt desires not to be inducted into the Hall. The conversation is theoretical, anyway, as there’s no real chance to consider Miller’s wishes from here: He’d asked not to be on the ballot at all. That, obviously, is done. (And, in any event, it’s hard to envision a nod at his desire now that wouldn’t throw the whole electoral endeavor into question. What—a formal statement that he didn’t want to be here? a plaque outside, rather than inside, the museum?) It makes Miller’s case distinct. But so does much of his candidacy, and, now, much of the context of his posthumous induction.

First, what Miller did: He built the structure of modern baseball. If that sounds hyperbolic, well, his work was so extensive that it should be. It’s true that there’s no precedent for a labor leader like him in the Hall, but there was no precedent for Miller. When he became the first director of the MLBPA in 1966, the game was fundamentally different. There was no arbitration. There was no free agency. There was no collective bargaining agreement (in baseball or any other professional sport). There was no secure future for the pension fund. The minimum salary had increased just once in the last twenty years—from $5,000 to $6,000—even as the season had been extended and baseball had started to regularly air on television, and so, of course, there was no foundation for a pay scale that increased as the game’s fortunes did.

Miller, in his first few years on the job, transformed all of this. He built solidarity where there had been little and created a fair labor model where there had been none. He established the basic economic system of professional baseball as it has endured for half a century. Or, as Hank Aaron put it: “Marvin Miller is as important to the history of baseball as Jackie Robinson.” Which, again, sounds hyperbolic only if you ignore the fact that it’s true.

As it comes to the Hall of Fame, to turn it over to another of the game’s most prominent citizens: “The criteria for non-playing personnel is the impact they made on the sport,” Bud Selig said in 2007, before Miller’s letter to the BBWAA. “Therefore Marvin Miller should be in the Hall of Fame.” (That’s, again, Bud Selig, not exactly the greatest fan of the union.) Yet the Hall chose several times not to include Miller and his work; Miller, at 91, requested that he not be considered for a private institution that did not match his values and had made clear it did not want him in an election process that he found “rigged.” And now, after he’s died, it has taken him in.

A Hall with Miller in it is fuller, with more of the game’s history, and a more accurate rendition of the story of the sport. It is better. This is as true now as it would have been in 2003, when he was first on the ballot. But, at the same time, the mechanism runs antithetical to the man and his work. There is no risk with an induction in death. There’s no speech and no chance for him to set his own terms. Instead, there is an opportunity for him to be sanitized or sanded down; there is a blank room to be filled; there is the opposite of all that he asked for here. In accordance with his wishes, Miller’s family does not plan to be part of the induction in Cooperstown. The Hall will do with him what it will.

“That is what makes Miller special to the history of the game, that he was the man who saw the absurdity inherent in The Natural Order of Things and took the trouble to expose it,” Bill James wrote in the introduction to Miller’s 1991 book, A Whole Different Ball Game. “While the economics of baseball today are bizarre to many of us, Miller was the first to see that the economics of baseball twenty-five years ago were bizarre in their own way. Miller was able, by the sheer logical force of the arguments he developed, to shatter an existing structure grown heavy with the weight of time. Anyone can see in retrospect the absurdities that Miller exposed, but what many people fail to see is that there is something quite improbable in the story of Marvin Miller himself.”

Miller, improbably, has revealed one last absurdity. The Hall of Fame is better with him in it. But perhaps he shouldn’t be there at all.