A juiced baseball scandal in Japan

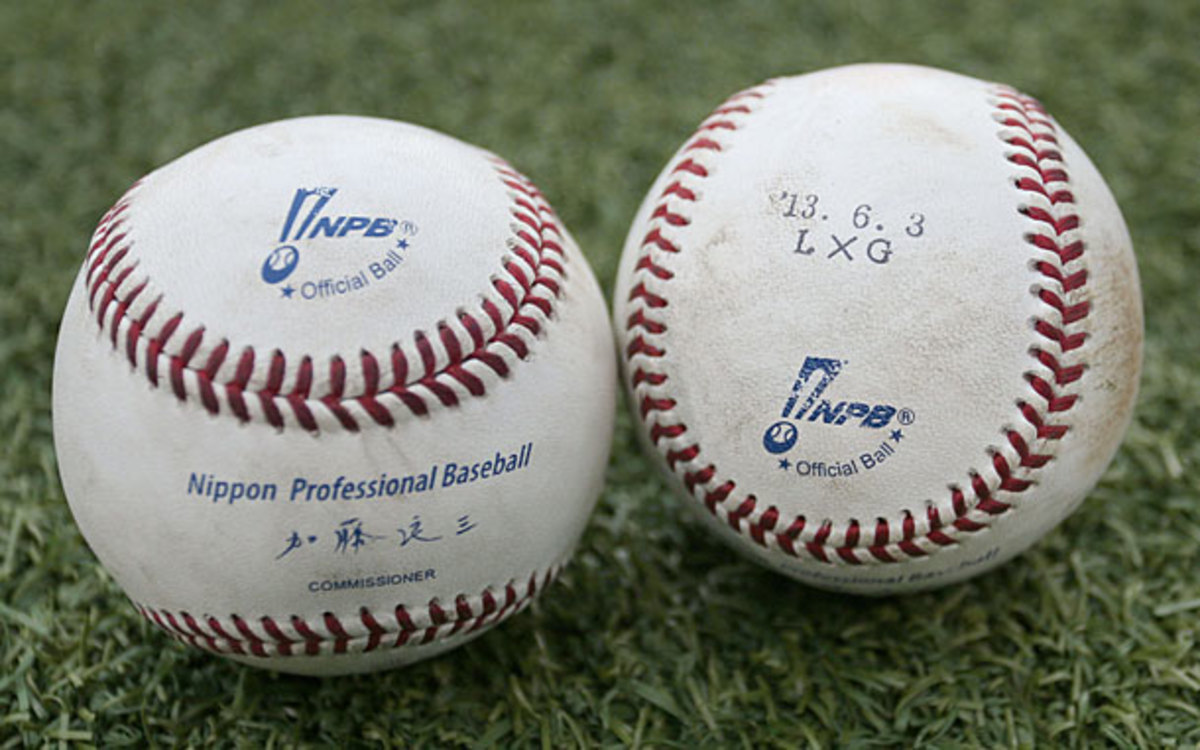

Baseballs in Japan were altered to help boost offense. (Landov)

League officials have copped to juicing baseballs in order to raise offensive levels. If that sounds like the light shining on a dark conspiracy regarding the high-offense era that ran through Major League Baseball from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s, it's not, though such a revelation is on my wish list. Instead, it's actually what has transpired in Japan, which is currently amid something of a home run boom.

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mfPuRoStEdw]

According to the Bangkok Post, after repeated denials, officials from the Nippon Professional Baseball have admitted that they asked equipment manufacturer Mizuno to alter the specifications of the ball in order to increase offensive levels, though that was to counteract a previous alteration. Back in 2011, NPB commissioner Ryozo Kato — who oversees the Japanese Central and Japanese Pacific Leagues — ordered a change in the makeup of the balls, which were slightly smaller and lighter than those used in MLB, to bring them in line with the stateside model. Wrote the Post, "The cork core of the ball was wrapped with a low-resilience rubber and its seams were widened. The organisation also made Mizuno the sole ball supplier, dropping its three rivals."

With the new ball, home runs rates dropped by more than 40 percent, from 0.93 per team per game in 2010 to 0.54 per game in 2011 and 0.51 per game in 2012 according to data from Baseball-Reference.com. The players' union, which felt that games had become less interesting, asked the league to review the matter. This year, the rates are back up to 0.75 per team per game, an increase of 47 percent but still well shy of pre-tinkering rates. From 2001 through 2005, they were above 1.0 per team per game, with a high of 1.25 per game in 2004. By comparison, in MLB, home run rates rose above 1.0 per game in 1994 and have been there ever since except for 2010 and 2011, peaking in 2000 at 1.17 per game; they're currently at 1.01 per game.

According to the Post, "Mizuno initially said the increase was due to foreign batters hitting so many home runs and was also related to the higher number of games being played in domed stadiums, where wind is not a factor," but the union chairman demanded a more honest reckoning. NPB secretary general Kunio Shimoda said the league asked Mizuno to "adjust" the ball to give it more bounce off the bat but demanded it remain silent. Kato, who denied knowing about the latest change — even when he had issued an order for the previous one — is now under pressure to resign.

Tinkering with the makeup of the baseball is hardly unprecedented. Obviously, it happened in the early part of the 20th century; in 1910, the cork center baseball was introduced, prefiguring the live ball era, which had a lot to do with using fresh baseballs instead of ones that had been beaten to a pulp as well. In 1931, the cushion cork center ball came along, using a composite mixture of cork and ground rubber which is encased in two rubber shells. As I found in researching chapters for Will Carroll's 2005 book The Juice and again in Baseball Prospectus' 2012 book Extra Innings, there's reason to believe that additional alterations of the ball may have played a part in various home run fluctuations, including the 1994-2009 one for which performance-enhancing drugs is inevitably blamed.

An excerpt of my work from the latter ran at Deadspin last August. Hitting a few highlights:

In 1974, the coating of the ball changed from horsehide to cowhide, coinciding with a 15 percent drop in per game home run rates. In 1977, when MLB switched ball manufacturers from Spalding to Rawlings, it coincided with a 50 percent jump in per-game home run rates. In the late 1980s, Rawlings moved its manufacturing operation from Haiti to Costa Rica, and somewhere along the way, balls switched from being hand-wound to being machine wound. In 1998, a diagnostic imaging company called Universal Medical Systems discovered via computerized tomography (CT) scans that a synthetic rubber ring unaccounted for in the official specifications had become part of the cork-and-rubber center, and that it appeared to vary in size from year to year; meanwhile, the density of the yarn wound around the ball had also changed over time. Forensic testing found a transition from all-wool yarns to increasingly synthetic ones.

For all of that, while tests have revealed structural changes to the ball, their performances haven't changed to as great an extent as one might think, at least according to rigorous lab testing done at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell and elsewhere. What has come to light is the extreme performance differences between balls at the outer edge of spec tolerances (PDF), as well as a lack of quality control. From Extra Innings:

In 2000, as balls were flying out of the park at record rates, Major League Baseball and Rawlings funded a study at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell Baseball Research Center; there a team of mechanical engineers led by Prof. Jim Sherwood put 192 unused 1999- and 2000-vintage balls through a battery of tests and accompanied MLB personnel on tours of the plants where various components were manufactured, issuing a 28-page report on their findings. The tests "revealed no significant performance differences and verified that the baseballs used in Major League games meet performance specifications." Yet they also found that "some of the internal components of the dissected samples were slightly out of tolerance on baseballs from each year … despite the thorough inspection process in place at the assembly plant in Costa Rica." Thirteen out of the 192 baseballs supplied (6.8 percent) were underweight as well.

The most glaring finding was the effect of the tolerances. According to the study, "two baseballs could meet MLB specifications for construction but one ball could be theoretically hit 49.1 feet further," which breaks down to 8.4 feet attributable to being on the light side of the tolerance for weight (5.0 ounces, as opposed to 5.25 ounces) and another 40.4 feet attributable to being on the high end for the coefficient of restitution (.578). Given that finding, it's not difficult to imagine how the slightest differences in the balls from batch to batch or year to year could lead to a plethora of towering 425-foot home runs instead of 375-foot warning track fly balls.

As physicist Alan Nathan, whose credentials include chairing the Society for Baseball Research's Baseball & Science Committee and serving on a scientific panel advising the NCAA on issues related to bat performance — which has included testing at the aforementioned Lowell lab, told me in an interview for the book, "The specs on major league baseballs, they almost don't deserve to be called specs, they're so loose that the range of performance from the top end to the bottom end is so different."