The tragic story of Charlie Mohr

The thing about Charlie Mohr was that never looked much like a fighter. He was long and lanky, and he wore horn-rimmed glasses and jackets and ties. For much of his short life, he dreamed of becoming a priest. It was easy to misjudge him. One day more than half a century ago, he showed up at a community center in Red Hook, Brooklyn, at an informal program of unsanctioned boxing matches. He toted his gym clothes and his books in a valise, and when a neighborhood tough guy spotted this square peg amid the crowd, he said, "I want that bleeping bleep."

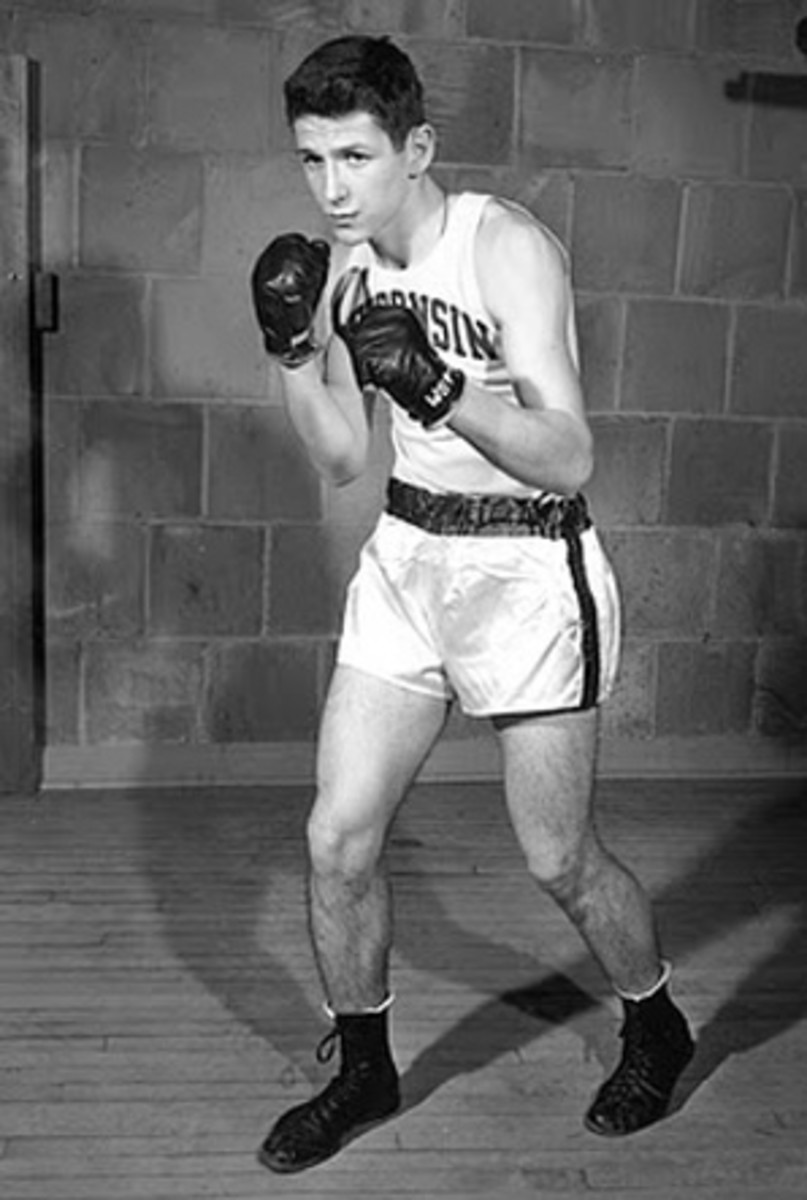

That was the first time Pete Spanakos laid eyes on Mohr, and Mohr defied every expectation. This goofy-looking southpaw from Long Island danced circles around his opponent. Soon, he would accompany Spanakos to the University of Wisconsin, each of them on a boxing scholarship. Back then, Wisconsin had one of the best college boxing teams in the country, and in his junior year, 1959, Mohr went undefeated and won the NCAA championship in the 165-pound weight class. He was also the most sensitive fighter anyone had ever met: He prayed for the opposition in the locker room and crossed himself in the ring. "Charlie was as sweet as they come," Spanakos says.

Fifty years after Mohr took a punch that sheared a blood vessel in his brain and eventually killed him, spelling the end for NCAA-sanctioned college boxing, this is how nearly everyone remembers him. By his senior year, he had become a hero in Madison, one of the most popular athletes in town. He worked as a houseboy at St. Paul's church and as a waiter at Paisan's restaurant. People invited him to their homes to speak. A nine-year-old boy named Tommy Moen met him one day when Mohr was selling programs at a Wisconsin football game -- Moen found a stray $5 bill on the ground, and walked over and asked Mohr if it was his. Mohr said it was, and he gave the kid a $1 reward. After that, Mohr and his girlfriend would go over to Moen's house to eat spaghetti and meatballs, and after fights he would use their phone to call his parents back home.

But even then, even as a campus idol, Mohr was wracked with worry. If anyone was too sweet for his own good, it was Charlie. The brutality of the sport, its primal nature, had never come naturally to him; Spanakos saw the way he'd dominate an opponent, and then back away before he could finish him off. The longtime coach at Wisconsin, John Walsh, called Mohr a "worrywart." Boxing was confusing enough, but Mohr was confused about many things. When some men made crude remarks about his sister while they were walking on campus, he couldn't bring himself to get physical with them; afterward, he told a teammate he considered himself a coward. At one point, according to the writer Jim Doherty,he entered into a relationship with a divorced mother of two. Between 1958 and 1960, Mohr was hospitalized at least once for a nervous disorder so serious that it required electroshock therapy.

By the time Wisconsin prepared to host the NCAA championships in 1960, Mohr was thinking of quitting boxing. His heart wasn't in it anymore. His memory was spotty. He had trouble deciding on the simplest things: When to eat lunch, when to study, when to work out. He had lost his desire to fight in the Olympics and the Pan-American Games. His teammate, Wally DeRose, went to Walsh -- who had retired in 1958, but was still deeply involved with the program -- and to his successor, Vern Woodward, and begged them not to allow Mohr to fight at the NCAA's. They didn't listen.

"Do you really want to do this?" DeRose asked Mohr.

"No," he said. But he felt obligated to his coaches, to the men who had given him a scholarship.

On April 9, Mohr stepped into the ring against San Jose State's Stu Bartell, a kid from the Canarsie section of Brooklyn, a casual friend that Mohr had gotten to know over the years. The bout would not only determine the 165-pound national champion, it would also determine the team championship between Wisconsin and San Jose State. Mohr just wanted it to be over. He'd already hinted to his friends it would be the last fight of his career.

*****

The truth about what happened that night has been obscured both by the passage of time and and by the collective will of a number of once-powerful men. For many years, no one -- including Doherty, who attended Wisconsin with Mohr and who wrote a definitive profile about him for Smithsonian magazine -- could seem to find a tape of the fateful second round of the fight. Had Charlie Mohr even been hit that hard, people wondered, as their memories began to cloud? A story surfaced after the fight that Mohr had died of an aneurysm. That he died in the ring, these people said, was merely bad luck; he could have died blowing his nose. Years later, Walsh didn't even recall that Mohr had been knocked down.

Eventually, a newspaper columnist named Doug Moe, while researching a book about the history of Wisconsin boxing called Lords of the Ring, unearthed a tape of the second round at a Wisconsin public television station. "He got hit hard," Moe says. "He went down, got back up, and then the referee stopped the fight."

Mohr walked back to the dressing room and apologized to his teammates. He was experiencing what's known as a "lucid interval"; inside his head, the damage had already been done. He lay down, complaining of a headache, and then he fell into convulsions. Outside the locker room, Stu Bartell, who would spend much of his adult life attempting to overcome his grief about Mohr, saw Tommy Moen standing there.

"I'm sorry I hurt your friend," he said.

Mohr was taken to the hospital and he was operated on by a neurosurgeon named Manucher Javid. There was nothing the doctor could really do except stabilize him; the blood vessel leading into Mohr's sagittal sinus had been detached by the force of the blow. For more than a week, Mohr remained in a coma, from which he never emerged. On Easter Sunday, April 17, 1960,he died.

All around Madison, there was anger and confusion. In a nearby church, a pastor announced the news and nine-year-old Tommy Moen burst into tears. "When you're that age, you don't know what death is," Moen says. "You just know this person you cared greatly about, and who cared about you, wasn't around anymore."

After operating, Javid informed another surgeon and prominent member of the medical school faculty, Dr. Anthony Curreri, who happened to be a former boxer and a supporter of the Wisconsin program. Curreri did not witness the operation, and Javid says he never mentioned an aneurysm. It came out anyway. There was a press conference, Javid recalls, and "it was absolutely nonsense."

Javid is certain Mohr suffered a subdural hematoma ("I remember everything about it," he says, "even though it was 50 years ago"), a collection of blood on the surface of the brain. But this was a time of great concern about the future of college boxing, about the notion of institutions of higher learning associating themselves directly with a sport that, at its highest levels, seemed increasingly unruly and barbaric (You Could Blame It On the Moms, read the headline on a 1959 SI story detailing those concerns). At Wisconsin, where thousands flocked to the campus fieldhouse for matches, where more than 10,000 had gathered to watch the NCAA Championships, men like John Walsh and Anthony Curreri had a vested interest in keeping it alive. And so the aneurysm story took hold.

Still, even this wasn't enough to save the program. The momentum against it was too strong. A group of Wisconsin professors rallied -- "The intelligentsia got together and decided boxing was too brutal a sport," DeRose says -- and just a couple of weeks after Mohr's death, the faculty voted to drop boxing altogether. Soon after, the NCAA announced it would do the same. There are still boxing clubs at schools across the country, but there are no scholarships, and the NCAA hasn't held an officially sanctioned championship since the day Charlie Mohr went down.

There are things we know about boxing that we didn't then -- about its cumulative impact, about its inherent dangers. For some, like Wally DeRose, or like Pete Spanakos -- who is working to start a boxing program at an intermediate school in the Bronx -- the benefits will forever outweigh the perils. "But when you get carried out of the ring," Spanakos says, "it's very dramatic."

And this is how Tommy Moen remembers it: Five decades later, just thinking about the first hero he ever had sinking to the canvas brings him close to tears. He's now a social worker at a housing project in Madison, and he has sons who play sports, and it terrifies him to imagine that his child might ever be as vulnerable as Charlie Mohr on the occasion of his final fight.

"To be honest," he says, "boxing kind of freaks me out now."