The curse of the No. 1 draft pick

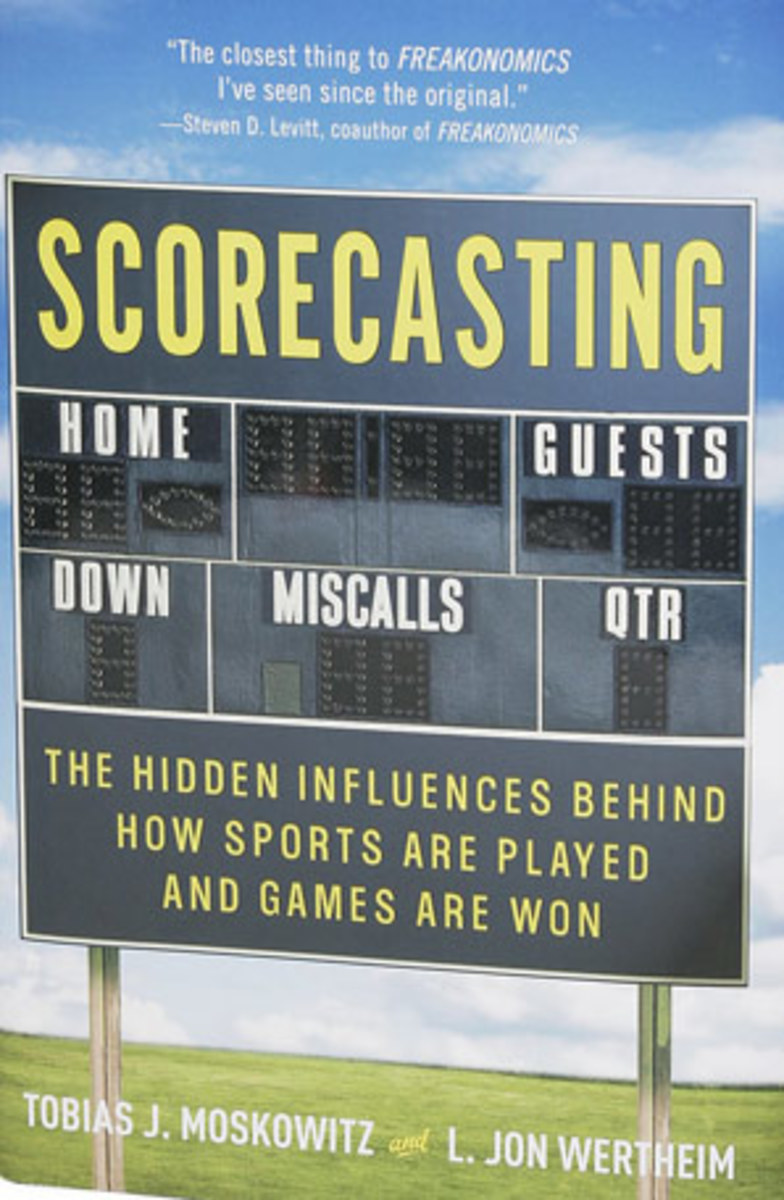

Excerpted from SCORECASTING: The Hidden Influences Behind How Sports Are Played and Games Are Won, by Tobias J. Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim. Copyright 2011 by Tobias J. Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim. Published by arrangement with Crown Archetype, an imprint of the Crowne Publishing Group, a division of Random House Inc., New York.

"Freakonomics for sports fans," the new book Scorecasting challenges conventional wisdom, uncovers the hidden influences in sports and uses reams of data to investigate questions that tug at every sports fan. Are there really make-up calls in the NBA? Is there, in fact, a home field advantage? Is there really no 'I' in team? In the following excerpt, the authors -- Chicago economist Tobias J. Moskowitz and Sports Illustrated writer L. Jon Wertheim -- consider the value of a top pick.

In 2004 Richard Thaler, a professor of behavioral economics at the University of Chicago, and Cade Massey at Yale were watching the NFL draft. With the first pick, the Chargers chose quarterback Eli Manning, the brother of perhaps the best quarterback in the league, Peyton Manning, and the son of longtime NFL quarterback Archie Manning. The Giants held the number four pick and were in the market for a premier quarterback as well. It was no secret they coveted Manning.

During the 15 minutes the Giants had to make their selection, they were ambushed with two very different options. Option 1 was to make a trade with San Diego in which the Giants would first draft Philip Rivers -- considered the second best quarterback in the draft -- and then swap him for Manning plus give up their third-round pick (number 65) that year as well as their first- and fifth-round picks in the 2005 draft. Option 2 was to trade down with the Cleveland Browns, who held the seventh pick and also wanted a quarterback. At number seven, the Giants probably would draft the consensus third best quarterback in the draft, Ben Roethlisberger. In exchange for moving down, the Giants would also receive from Cleveland their second round pick (number 37) that year.

The Giants chose the first option, which meant they effectively considered Manning to be worth more than Roethlisberger and four additional players.

To the two economists, however, this seemed like an extraordinarily steep price. But after collecting data from the NFL draft over the previous 13 years and looking at trades made on draft day as well as the compensation -- salaries plus bonuses -- paid to top picks, they found that the Manning trade was anything but unusual. As a matter of routine, if not rule, teams paid huge prices in terms of current and future picks to move up in the draft. They also paid dearly for contracts with those players.

Not only did Manning cost the Giants four other players -- one of whom turned out to be All Pro linebacker Shawne Merriman -- but he was also given a six-year, $54-million contract. Compare this to Roethlisberger's compensation. Ultimately drafted 11th by the Steelers, he received $22.26 million over six years.

Thaler and Massey found that historically, the number one pick in the draft is paid about 80% -- 80%! -- more than the 11th pick on the initial contract. The economists also found that the inflated values teams were assigning to high picks were remarkably, if not unbelievably, consistent. No matter the circumstances or a team's needs, teams routinely assigned the same value to the same pick.

Thaler and Massey compared the values teams placed on picks -- either in terms of the picks and players they gave up or in terms of compensation -- with the actual performance of the players. They then compared those numbers with the performance of the players given up to get those picks. For example, in the case of Manning, how did his performance over the next five years compare with that of Rivers plus the performances of the players chosen with the picks the Giants gave San Diego? Likewise, how did those numbers stack up against Ben Roethlisberger's stats and those of the players the Giants could have had with the additional picks they would have received from Cleveland?

The economists looked at each player's probability of making the roster, his number of starts, and his likelihood of making the Pro Bowl. They found that higher picks were better than lower picks on average and that first rounders on average post better numbers than second rounders, who in turn post better stats than third-round draft picks, and so on.

The problem was that they weren't that much better. Even looking position by position, the top draft picks are overvalued. How much better is the first quarterback or receiver taken than the second or third quarterback or receiver? Not much. The researchers concluded the following:

• The probability that the first player drafted at a given position is better than the second player drafted at the same position is only 53%, that is, slightly better than a tie.

• The probability that the first player drafted at a position is better than the third player drafted at the same position is only 55%.

• The probability that the first player drafted at a position is better than the fourth player drafted at the same position is only 56%.

In other words, selecting the consensus top player at a specific position versus the consensus fourth best player at that position increases performance, measured by the number of starts, by only 6%. And even this is understating the case, since the number one pick is afforded more chances/more starts simply because the team has invested so much money in him. Yet teams will end up paying, in terms of both players and dollars, as much as four or five times more to get that first player relative to the fourth player. Was Manning really 50% better than Rivers and twice as good as Roethlisberger? You'd be hard put to convince anyone that Manning is appreciably more valuable than Rivers or Roethlisberger; in any event, he's certainly not twice as valuable.

Yet this pattern persists year after year. Is having the top pick in the NFL draft such a stroke of good fortune? It's essentially a coin flip, but not in the traditional sense. Heads, you win a dime; tails, you lose a quarter. Massey and Thaler go so far as to contend that once you factor in salary, the first pick in the entire draft is worth less than the first pick in the second round.

Thaler and Massey discovered another form of overvaluation as well: Teams paid huge prices in terms of future draft picks to move up in the draft. For example, getting a first-round pick this year would cost teams two first-round picks the next year or in subsequent years. Gaining an additional second-round pick this year meant giving up the first- and second-round picks next year. Coaches and GMs seemed to put far less value on the future. Looking at all such trades, the so-called implicit discount rate for the future was 174%, meaning that teams valued picking today at nearly three times the value of taking the same pick in the next year's draft! Think of this as an interest rate. How many of us would borrow money at an annual interest rate of 174%? Even loan sharks don't come close to this rate.

Why do NFL teams place so much value on high picks? We tend to overpay for an object or a service when its value is uncertain and we're in competition with other bidders. There's even a term for this: winner's curse. To demonstrate the winner's curse, a certain economics professor has been known to stuff a wad of cash into an envelope, stating to his students that there is less than $100 inside. The students bid for its contents; without fail, the winning bid far exceeds the actual contents -- sometimes even exceeding $100! (The surplus is used to buy the rest of the students pizza on the last day of class.) The top pick in the NFL draft, by its very nature an exercise in speculation, is singularly ripe for the winner's curse.

Here's another factor in the overpayment of draft picks: As a rule, people are overly confident in their abilities. In a well-known study, people were asked at random whether they were above-average drivers. Three-quarters said they were. Similarly, between 75% and 95% of money managers, entrepreneurs and teachers thought they were above average at their job. How many times are hiring decisions made because a boss is convinced that in a 30-minute interview she's found the best candidate? She's just sure she's right. In the same way, general managers (and sometimes interfering owners) tend to overestimate their ability to assess talent. They trust their guts too much and overpay as a result.

Overvaluing because of gut instincts also helps explain why teams invest so much in this year's pick and so little in next year's prospects. The guy in front of you is a once-in-a-lifetime player, a term invoked at almost every draft. The guy next year is just an abstraction. (Another explanation for the immediacy: GMs and coaches typically have short tenures, so winning now is imperative. Even a year can seem beyond their horizon.)

The truth is that evaluating talent is hard. How hard? For an illustration, consider the case of Eli Manning's older brother, Peyton. In 1998, Peyton entered the NFL draft with tremendous hype. But teams weren't sure whether he would be the first or second quarterback taken. There was a comparably touted quarterback from Washington State, Ryan Leaf, considered by many NFL scouts to be the better prospect. Leaf was bigger and stronger than Manning, and with the support of his college numbers, he was regarded as the better athlete. The Chargers held the third pick of the draft but made a trade with the Cardinals to move up to the second pick to ensure that they got one of the two tantalizing quarterbacks. This move cost them two first-round picks, a second- round pick, reserve linebacker Patrick Sapp and three-time Pro Bowler Eric Metcalf -- all to move up one spot! In the end the Colts, holding the number one pick, took Manning.

The San Diego Chargers took Leaf with the second pick and signed him to a five-year contract worth $31.25 million, including a guaranteed $11.25 million signing bonus, at the time the largest ever paid to a rookie -- that is, until the Colts paid Manning even more: $48 million over six years, including an $11.6 million signing bonus.

You probably know how the story unfolded. Peyton Manning is the Zeus of NFL quarterbacks, a four-time MVP (the most of any player in history) and a Super Bowl champion riding shotgun on the express bus to the Hall of Fame. And Leaf? After three disastrous seasons, he was released by San Diego.

To their credit, the Chargers learned from their costly mistake. In 2000 they finished 1-15 and were "rewarded" with the top pick in the 2001 NFL draft. They traded the pick to Atlanta for the Falcons' number five pick as well as a third-round pick in '01, a second- round pick in '02 and Tim Dwight, a wide receiver and kick-return specialist. The Falcons used the top pick to select Michael Vick; the Chargers used that fifth selection on LaDainian Tomlinson, who would become the most decorated running back of his generation. To satisfy their quarterback needs, the Chargers waited until the first pick of the second round and tapped Drew Brees, who would go on to become the 2010 Super Bowl MVP, albeit for Saints. Remember, too, the Chargers gave up Eli Manning in 2004 for Philip Rivers and the right to choose Shawne Merriman.

Beyond the money, overinvestment in high draft picks can have other costs. Pampering an underachieving first-round pick -- treating him differently from the sixth-rounders who'd be put on waivers for a comparably dismal performance -- exacts a price on team performance and morale. It also forestalls taking a chance on another athlete. The more chances given Leaf during his three seasons with the Chargers, the fewer chances afforded his backup. And it's not just the team that has drafted the player that's prone to this fallacy. Even after Leaf's miserable performance and behavior in San Diego, three other teams gave him another shot. They still believed the hype. "It'll be different here," they told themselves.

If you look at the top pick in the NFL draft from 1999 to 2009, not a single one was named rookie of the year on either side of the ball. More damning, many of the top picks have turned out to be busts. Of the last 11 number one picks, eight have been quarterbacks. Four of them -- Tim Couch, David Carr, Alex Smith, and the beleaguered JaMarcus Russell -- came nowhere close to justifying the selection. Of the four remaining quarterbacks, it's too early to tell what will become of Matthew Stafford in Detroit, and though Carson Palmer and Michael Vick have each been to the Pro Bowl, both have also spent considerable time on the sidelines. That leaves only one number one quarterback pick, Eli Manning, who has started the majority of games for his team since his debut.

But again, divergent as their careers have been, all the number one picks were paid handsomely. So for the teams selecting at number one, the best-case scenario is that you buy a Camry at Porsche prices. Worst-case scenario, you pay Porsche money for a clunker. What you never get is a great player at a cheap price. In the 2010 draft, the trend continued as the Rams selected quarterback Sam Bradford number one (making nine of the last 12 first picks QBs) and signed him to the richest contract in history -- five years at $86 million, with $50 million guaranteed.

Even with successful high picks on the order of Manning and Palmer, the question isn't how much they cost in salary but also how much they cost in draft picks you could have had instead. In 2005, the 49ers drafted Alex Smith with the first pick; the only quarterbacks from the 2005 draft to have made a Pro Bowl are Aaron Rodgers (number 24), who made it for the first time in 2009, and Derek Anderson, the 11th quarterback taken that year. In 2000, defensive end Courtney Brown was chosen number one. He never made a Pro Bowl. But Shaun Ellis and John Abraham, the second and third defensive ends taken in that draft, did make numerous Pro Bowls. As did Kabeer Gbaja-Biamila, the 12th defensive end taken that year, with the 149th pick, and Adewale Ogunleye, who wasn't even drafted that year, meaning that at least 24 defensive ends were chosen before him. Bottom line: In football, it's very hard to tell who is going to be great, mediocre, or awful.

So what should a team do if it's blessed (which is to say, cursed) with a top pick? Trade it, as the Chargers learned to do. Drafting number 10 and number 11 instead of number 1 is a much better proposition. With two draws, the chance of having at least one of the two picks succeed is much higher, and the cost is the same or less. Factor in the potential for injuries and off-the-field trouble, and it becomes even more apparent that having two chances to find a future starter is a much better proposition than having only one. Also, the team avoids the potential of a colossal public bust like Leaf. Even if the later picks flop, fans won't care nearly as much as they do when the top pick is a bust.

Over the last decade, two teams in particular created a new model, placing less value on the top picks: the Patriots and the Eagles. Not surprisingly, they have two of the top winning percentages and five Super Bowl appearances since 2000. Tom Brady, one of the few quarterbacks hailed as Manning's equal? He was drafted in the sixth round of the 2000 draft, with the 199th pick, and thus was obtained cheaply, leaving the Patriots with extra cash for other talent to surround him. Teams that traded draft picks for future ones benefited in subsequent years, too -- and again, the Patriots and Eagles were at the forefront. (Not coincidentally, their coaches, Andy Reid and Bill Belichick, have enough job security to afford the luxury of a long-term focus. Reid even has the additional title of executive vice president of football operations.)

Which teams are on the other end of the spectrum, routinely trading up in the draft to get higher picks and overpaying for them? The answer is unlikely to surprise you: the Raiders and the Redskins, who collectively have the fewest number of wins per dollar spent of all teams in the NFL.

To purchase a copy of Scorecasting, go here.