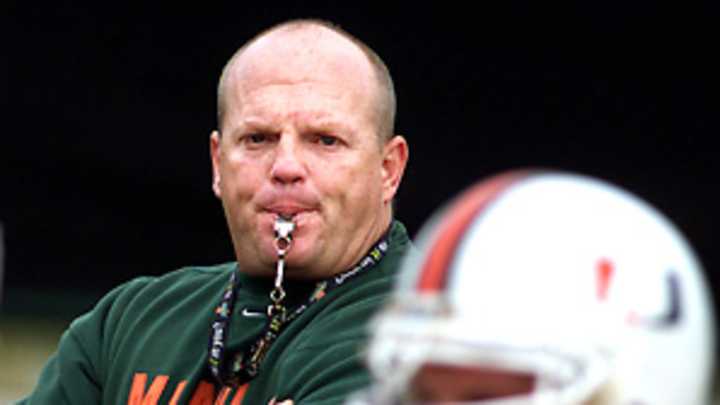

Art Kehoe never quit loving Miami; now, Miami again loves him back

The red Cadillac DeVille sat in a parking lot overlooking Vaught-Hemingway Stadium on the Ole Miss campus. Inside, a bald man built like a fire hydrant bellowed into his iPhone. In fact, the Caddy sat in this particular parking lot because of Art Kehoe's iPhone.

Only a few locales in metropolitan Oxford, Miss., delivered the precious bars that allowed Kehoe to make the calls that kept his dream alive. Of those locales, he had two favorites. One was a Subway inside a Wal-Mart. It offered the trifecta -- bars, a place to sit and sandwiches. The other was the parking lot. So on Sunday, Jan. 23, Kehoe sat in the red Caddy as freezing rain fell. He held the iPhone to his ear.

"You ready to come home to the family?" the voice on the other end of the line asked. Kehoe couldn't believe his ears. He had to make sure the bars hadn't fluctuated and forced his brain to fill in the blanks with words he'd assumed he'd never hear. "What?" he yelled. "Are you kidding me?" The caller assured Kehoe he wasn't kidding. With that, Kehoe put the phone on his leg, rolled down the window, stuck his head out into the ice-cold rain and screamed.

*****

CORAL GABLES, Fla. -- In March 2009, a more famous bald football coach than Kehoe sat down for an interview with author Clay Travis. Phillip Fulmer, a Tennessee alumnus whose blood will always run that particular shade of orange, had tears in his eyes when he discussed his firing a few months earlier.

"You can love a university, but the university can't love you back," Fulmer told Travis. "It's just bricks and mortar."

That isn't always true.

Sometimes -- once in a great while -- a university can undo a mistake. What was wrong can be set right. Sometimes, a university can open its arms to a dedicated servant it once tossed aside and welcome him back with an embrace he didn't believe possible.

For 27 beautiful years, no one loved the University of Miami the way Kehoe did. Kehoe played two seasons for the Hurricanes and then coached the offensive line for 25. He worked for five head coaches. He won five national titles.

Then, on Jan. 2, 2006, head coach Larry Coker called Kehoe into his office. "I don't know how long everybody else's deal was," Kehoe said. "Mine took about a minute." Kehoe and three other assistants were gone. The university he'd loved had tossed him out like trash. But even after he sued the university -- and won -- for unpaid wages, Kehoe still loved Miami. When he coached the offensive line at Ole Miss for two seasons, he still loved Miami. When he volunteered at NAIA school Lambuth in Jackson, Tenn., he still loved Miami. When he subbed for an ailing coach at Louisiana Tech, he still loved Miami. When he coached two seasons in the United Football League, he still loved Miami.

But until he sat in that Caddy screaming into the freezing rain, Kehoe, 53, had always assumed Miami would never again love him back.

*****

Al Golden asked Kehoe if he wanted to fly down the following day. No, Kehoe said. He wanted to drive. That way, he wouldn't have to come back for his belongings. He could just work. But first, he had to go home and break the good news. His wife, Diona, had headphones covering her ears when Kehoe arrived. At first, she couldn't hear him, couldn't decipher the goofy grin. Finally, the headphones were shed and the message was delivered. "You're looking at the new line coach at Miami!" Kehoe said. To hear Kehoe tell it, Diona would have set a high-jump record when she leapt into his arms. Kehoe packed his things, hugged son Jake and stepdaughter Madison and pointed the Caddy toward Coral Gables.

*****

Kehoe's 27-year association with the University of Miami began with what some might consider a fib. The Conshohocken, Pa., native with the bullhorn for a voice box considers it more of a gentle stretching of the truth. A two-inch stretch, to be precise.

Back in the late '70s, back when he had hair, Kehoe lived for a while on a couch in the coaches' office at Laney Junior College in Oakland, Calif. When coaches from four-year schools would come through to watch game film, Kehoe, Laney's nose guard, always offered the same advice. "Make sure you look at No. 66," he would say.

That method drew some interest, as did the Laney coaches' trip to a convention that led to multiple offers for the sophomore. But Kehoe, whose teammates revered him for having keys to seemingly every door at Laney, had snagged an athletic department copy of the NCAA directory and had a different destination in mind. Among the capsules describing each school and offering a list of athletic department phone numbers, Kehoe found the entry for Miami. "Palm trees, beaches," Kehoe said. "They play Notre Dame, Penn State, Florida State, Florida, Alabama. Their schedule was ridiculous."

So Kehoe called Miami. Collect. He told the operator to tell the person who answered that Coach Kehoe was on the line. Miami head coach Lou Saban answered. First, "Coach Kehoe" explained that he wasn't really a coach. Then he asked Saban if he needed a nose guard. Saban said he did. Kehoe said he had great film if Miami coaches wanted to see it. Then he told that fib. "I said I was 6-2, 245," Kehoe said. "I was 6-foot, 230."

Saban bit, and Miami began recruiting Kehoe. He worried that recruitment would end when he arrived for his official visit. When the plane touched down, Kehoe met Miami assistants Mike Archer and Harold Allen. Archer shot Kehoe a sideways glance. Allen, Miami's legendary defensive line coach, couldn't hold his tongue. "Hell, son," Allen said, looking Kehoe up and down. "Did you shrink on the flight?" Kehoe decided brutal honesty was his only option. "Coach," he said, "I'm tryin' my ass off to get a scholarship."

Kehoe got that scholarship, and he arrived at Miami in 1979. That same year, Howard Schnellenberger replaced Saban. Schnellenberger dreamed even bigger than Kehoe. Where others saw a respectable, middle-of-the-road program, Schnellenberger saw a potential national champion. Kehoe was moved to offense, where he started at guard for two years -- he protected quarterback Jim Kelly as a senior -- and forged lifelong friendships with teammates such as Jim Burt and Tony Chickillo. He served as a student assistant coach in 1981. He won his first national title ring as a graduate assistant in 1983. In 1985, Kehoe was promoted to offensive line coach.

He would win four more national title rings, but according to him, his line never blocked a soul from Monday through Thursday. Miami's defensive lines, which featured Cortez Kennedy, Jerome Brown, Warren Sapp, Vince Wilfork and a host of other future NFL stars, were simply too good. Kennedy's senior season in 1989 was especially frustrating for Kehoe. After Kennedy slimmed from 370 pounds to 295, he turned completely unblockable. "We went 0-for-500 against him," Kehoe said. "We never blocked anybody."

Except on Saturdays, when the Hurricanes blocked everyone.

Kehoe coached seven first-team All-Americans at Miami, beginning with Leon Searcy in 1991 and ending with Eric Winston in 2005. He also recruited the heck out of Florida's West Coast. He was the point man in the recruitment of tailback Edgerrin James from the Everglades-adjacent town of Immokalee. He also built an offensive line pipeline from Canada, recruiting future All-America guard Rich Mercier from Toronto in 1995. Later, he landed center Brett Romberg from Windsor, Ontario, and guard Sherko Haji-Rasouli from Toronto.

In 2002, Romberg told SI about meeting Kehoe at a camp in his hometown. "It was a gloomy day, and there was this stumpy guy with a tan," Romberg said. "Every time he walked by me, he'd whisper, 'Miami.'"

To Kehoe, that was the ultimate recruiting pitch. Miami. A "U" on the helmet. Who needed more?

By the end of 2005, Kehoe had all he ever wanted. He had Diona. He had Madison. He had Jake, whose 2004 birth he had to rush from practice to attend. He had Miami.

Then, just like that, Miami was gone.

"I thought maybe I didn't spend 27 years there," Kehoe said. "It's like you're lost out at sea."

Coker had become convinced he needed to shake up his staff to improve chemistry. Kehoe, offensive coordinator Dan Werner, running backs coach Don Soldinger and linebackers coach Vernon Hargreaves were fired two days after the Hurricanes' 40-3 loss to LSU in the Peach Bowl. Miami had lost by more than a touchdown only once in the previous five seasons. From 2001-05, the Hurricanes went 53-9. In the five seasons since, they've gone 35-29.

*****

Soldinger, who worked with Kehoe at Miami from 1995-2005, calls the man "human espresso." Indeed, Kehoe does seem to inject a burst of caffeine whenever he walks into a room. But as he drove through the night, through Tupelo, Miss., and Birmingham, Ala., before taking a hard right at Atlanta and heading south, Kehoe needed something extra. Every so often, he'd stop and slug a 5-Hour Energy shot. When those didn't work, he stopped at a rest area, got out and let the icy air slap him in the face. Then he did his best Jack LaLanne impression, stretching every possible direction to keep his neurons firing so he could keep driving toward his dream come true. If anyone drove by, they probably thought he'd lost his mind. What else could they think? After all, how often do you see a 53-year-old man in the dead of a freezing night standing outside a rest area doing calisthenics?

*****

Kehoe doesn't want to talk about the firing. He doesn't want to talk about the lawsuit. "I want to bury it," he said.

What good would bitterness do now? Like a lot of people the past few years, Kehoe lost a job unexpectedly and had to move from a house he couldn't afford to keep and -- thanks to a crashing real estate market -- could barely afford to sell. "I just got crushed on it," he said. "But it is what it is. At least I got rid of it."

Kehoe couldn't help getting angry at the time, though. "Everybody in this country has been going through hardships," Kehoe said. "A truckload of people have lost everything they've worked for. It's hard times on a lot of people. I happened to be one of the people going through it, too. When you're going through it, you get a little perturbed."

Kehoe did get lucky at first. Former Miami colleague Ed Orgeron hired Kehoe and Werner at Ole Miss, but after two seasons, the staff was fired. In 2008, Kehoe worked briefly as a volunteer assistant for former Ole Miss assistant Hugh Freeze at Lambuth College, but Kehoe didn't stay long. That August, Louisiana Tech coach Derek Dooley hired Kehoe to fill in for Petey Perot while Perot recovered from heart surgery. Kehoe coached the line that season, and Perot returned in time for the Independence Bowl.

Temp duty didn't lead to a full-time college job, so Kehoe found himself in the Subway inside the Wal-Mart, calling old friends and chasing leads. The Subway was perfect, he said, because even when it got busy, there was always a corner in which he could sit in relative privacy. The Subway also was noisy enough that Kehoe didn't bother diners with his frequent, occasionally salty outbursts. "I'm a loud talker," he said. "I get excited."

Kehoe coached the past two seasons in the UFL, first for the California Redwoods in 2009 and then for the Sacramento Mountain Lions in 2010. When he returned to Mississippi after the season, he returned to the rumor mill at FootballScoop.com and to the phone in the Subway and in the parking lot. He hoped for a return to major college football, but he couldn't find an opening.

When Miami fired head coach Randy Shannon in November, Kehoe took note. But a return still didn't seem like a realistic possibility. Jeff Stoutland, the Hurricanes' respected offensive line coach, was named interim coach, and Stoutland was retained after Miami hired Temple coach Golden as Shannon's permanent replacement. Then, last month, Kehoe saw a small crack of light in the darkness of his job search.

Rumors flew that Stoutland planned to leave Miami for Alabama. When those rumors proved true, Kehoe told his wife he might have a chance to come back. "Dee, I gotta get back on board," he told her. Kehoe called a few old friends from Miami and asked them to lobby for him. A few days later, he sat in the parking lot outside Vaught-Hemingway Stadium and talked to Golden for 45 minutes.

Suddenly, the possibility of a homecoming seemed quite real. So Kehoe unleashed 27 years worth of Hurricanes upon Golden. Golden, who was feverishly recruiting, didn't take many of the dozens of calls on Kehoe's behalf, but he got the message. Besides, Golden already knew all about Kehoe. He knew he could coach an offensive line, and that mattered more than any recommendation from an alum. What mattered even more to Golden was the love for Miami that came blasting through the phone when he spoke to Kehoe. "The first thing I touched on when we came to Miami was that we have to get back to guys who want to be Miami Hurricanes," Golden said. "There's something to be said for that. If I think that applies to recruits, why wouldn't it apply to our staff?"

Golden formally interviewed Kehoe in Greenwood, Miss., on Jan. 20. Three days later, he delivered the good news. Golden has no doubt that he has never dealt with anyone happier to be hired than Kehoe was that day. "Unequivocally, no," Golden said.

Perhaps the most amazing thing to Golden was that despite the firing, despite the lawsuit, despite everything, Kehoe still loved Miami as much as he did as a player. "It didn't diminish his love for the university or the football program," Golden said. "That sums it up."

When Kehoe arrived back in Coral Gables, he went straight to work. Because he was an ex-employee, he had to be revived in Miami's human resources system. On his first full day of work, he had to track down a copy of his last Miami pay stub. Then he had to fill out form after form and take a drug test. The next day, he had to take the NCAA recruiting test so he could go on the road and give last-ditch pitches to prospects who didn't know this Miami staff. He passed the test on the afternoon of Jan. 26. At 3:30 p.m. that day, Kehoe was told he had a flight leaving Miami International Airport in two hours.

He didn't have time to park in a proper lot, so Kehoe parked in the American Embassy lot across from the terminal. He didn't have Miami business cards yet, so he pulled out an old UFL card and wrote on the back. "My name is Art Kehoe," he wrote. "I just got hired at the University of Miami. Please don't tow me. I'll be back tomorrow." Kehoe tossed the card onto the dashboard and sprinted to the terminal.

Inside, an airline employee recognized Kehoe from a newspaper story about his hiring. The employee quickly checked in Kehoe and gave him directions to the shortest security line. Kehoe made his flight, which landed in Jacksonville. There, Miami linebackers coach Michael Barrow would pick up Kehoe and drive him to meet Ed White High lineman Kaleb Johnson, who eventually would sign with Rutgers. After he deplaned, Kehoe had a few minutes to wait before Barrow picked him up. He figured he would read through the media guide to hone his pitch, even though he probably didn't need to. "You don't need a media guide," Soldinger said of his old friend. "Just ask Art. He's a walking encyclopedia."

Kehoe spotted the perfect place to work. A Quizno's. Just like that Subway in the Wal-Mart, he had all he needed. A seat. Mobile phone bars. Sandwiches. A "U" on his polo shirt. "Here we go," Kehoe said. "I was so happy."

*****

Kehoe could have flown from Mississippi to Miami, but a 1,000-mile victory ride felt so much better. Sometimes, a man needs to feel every inch of earth beneath his tires to appreciate the distance between what he lost and what he's regained.

The U.S. Interstate system reaches its southernmost point when I-95 dead-ends into U.S. 1 in Coral Gables. As Kehoe drove down the ramp on the afternoon of Jan. 24 and merged onto the stretch known as South Dixie Highway, the palm trees danced in the breeze. He couldn't stop smiling.

Finally, he was home.