Did the Cubs really win the 1908 World Series? Maybe not

The Apache chief Geronimo was still alive, as were the outlaws Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, not to mention the former slave Harriet Tubman, and the first nurse, Florence Nightingale, and the writers Mark Twain and Leo Tolstoy. Every one of them was drawing breath on October 14, 1908, and thus capable of seeing the Chicago Cubs win the World Series that afternoon, something they rather famously haven't done again in 103 years.

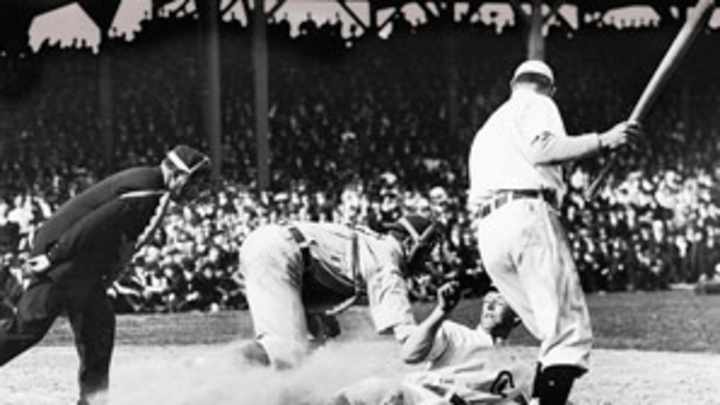

Except, of course, that none of them did see the Cubs win that World Series. Nobody did. Or very nearly nobody. The fifth and clinching game of the 1908 Series was in Detroit, in front of what remains the smallest crowd in the history of the Fall Classic. Only 6,210 people bore witness to this mystical event, a figure so small -- the population of Iron Station, N.C. -- that one is tempted to ask whether the Cubs won that World Series after all.

Yes, there exist contemporary accounts of the final out, which came when Tigers catcher Boss Schmidt succumbed to Cubs pitcher Orval Overall, a name so good that you might think it was invented: He certainly sounds like a fiction, and a bad one at that, but let's take it on faith that the Cubs did win the 1908 World Series behind a citrus farmer named Orval Overall, of Farmerville, Calif.

We'll have to. The game is not in the living memory of a single human being. The average life expectancy for men in 1908 was 49.5 years, so that the few eyewitnesses to that victory -- among players and spectators alike -- were becoming scarce even by World War II. It is now customary for athletes to say after winning a championship, "No one can take this away from us," but perhaps we should make an exception for the 1908 Cubs, not because they didn't prevail over the Tigers in five games, but because it's possible that the 1908 Cubs were not of this world.

We owe it to history to at least consider that those Cubs were -- and I beg your patience here -- aliens from outer space.

To understand how this could be -- and I readily accept your skepticism -- we must go back to 1908. To say that it's been a long time since the Cubs won the World Series sounds like a statement of the obvious but is something closer to the opposite. It's exceedingly difficult to fully comprehend just how long it has been. The year 1908 is as distant to us now as the year 1805 was to those Cubs. They are to us what President Jefferson, Lewis & Clark and Napoleon Bonaparte were to them: Men who were in their primes 103 years previously.

From our purview, 1908 looks like the beginning of time, but in fact it was a year of dizzying technology, expanding humanity's boundaries like few years before or since. Oil was discovered in the Middle East, in Persia, giving men something to put in their Model Ts, which Henry Ford began selling for $850 in 1908. The mass-market automobile was not the best thing since sliced bread --it predated sliced bread -- but it was a life-changing, world-shaping creation. That same summer, Wilbur Wright made his first public flight, in France, and Admiral Robert Peary set off, by ship, for the North Pole, as the Chicago Cubs traversed America by train.

The team was in Cincinnati on June 30, 1908 -- a game behind Pittsburgh in the standings -- when something inconceivably large came into violent contact with the other side of the planet, in Siberia. The night sky lit up, as if in flames. The ground trembled. As NASA would describe the scene a century later, 800 square miles of forest were felled, and 80 million trees were lain out in a circle like the spokes of a bicycle, each tree pointing away from a central hub in an area so remote that scientists would not inspect the site until 19 years later.

The Tunguska Event, as it came to be known, was a puzzle, a trauma of inexpressible magnitude in which not a single human life was lost. In 2008, NASA suggested the cause was an asteroid, 120 miles across, weighing 220 million pounds, entering the Earth's atmosphere at 33,500 miles per hour, heating the surrounding air to 44,500 degrees Fahrenheit, causing the asteroid to explode 28,000 feet above the surface of the Earth, setting off seismographs in England, where Londoners could read a newspaper by the light of the night sky.

Or it might have been a benevolent race of aliens intercepting a meteor to save the Earth from certain destruction, as a Russian scientist named Dr. Yuri Lavbin asserted, to considerable international press coverage, in 2009.

If any Good Samaritan Martians disembarked on our planet, and spent a celestial layover here dispensing kindnesses, they quickly dispersed and assimilated into the population, for none was ever discovered. Suffice to say that the Cubs -- 14 games above .500 at the moment of impact -- played their best baseball in the second half of the season, winning 23 of their last 29 games, finishing 44 games above .500 and benefiting down the stretch from a salubrious and supernatural mojo of precisely the kind that has worked against them ever since.

In September 1908, as the Cubs were winning the pennant with the help of Fred (Bonehead) Merkle's immortal baserunning error for the Giants, a comet began appearing in the night sky to greet them. The Comet Morehouse -- named for its American discoverer, Daniel Morehouse -- was never the same comet twice. It was sometimes six-tailed, for instance, and sometimes trailing a tail disembodied from its head.

"Many violent outbursts with complete changes in the shape of the tail were photographed at different observatories," according to a study published in 1928 by Dr. N.T. Bobrovnikoff of the University of California's Lick Observatory. "One of the most striking explosions occurred on October 14, 1908. It has been the subject of several investigations, but the problem of the motion of these cloud-like masses cannot be regarded as solved."

These "striking explosions" in the sky weren't the only unsolved and unnatural phenomena that Wednesday, October 14, 1908. The Chicago Cubs, before a few eyewitnesses, won the World Series.

As another season goes down the tubes for the North Siders, it is worth considering that those 1908 Cubs weren't men at all but a team of beneficent extraterrestrials, whose victory -- however happy and well-meaning a gift to mankind -- should nevertheless be vacated. It is the World Series, after all, and those Cubs were otherworldly.

How can we know? The truth is out there. It wasn't just the literal collision of worlds above Siberia, or the congratulatory winking of the Comet Morehouse that tell us, but something in that very year, 1908. Say it out loud -- Oh eight" --and it will soon sound like an order: "Oh eight, oh eight, oh wait, oh wait, oh wait."

Tolstoy, the Russian novelist, turned 80 in 1908, and would have felt the impact of Tunguska. "The two most powerful warriors are patience and time," he wrote, as if speaking directly to the current Cub faithful, whose members are ever so patient, but no match for time. And so they keep waiting for their ship to come in, those Cub fans, when they should be waiting for it to land.