Study shows dramatic jump in HGH use by high school teens

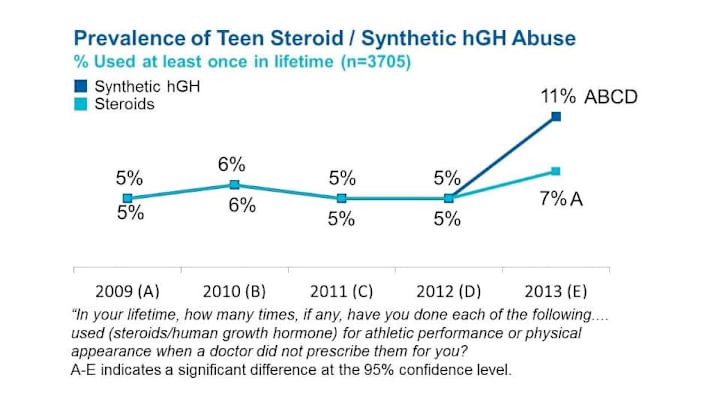

The use of non-prescription human growth hormone (HGH) among teenagers in grades 9-12 doubled last year, according to a report by the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids released on Tuesday. Data from an anonymous survey of 3,705 high school students randomly selected across the U.S. shows a jump in the number of teens who admit having taken HGH at least once in their lifetime from 5 percent in 2012 to 11 percent last year.

HGH controls muscle and bone growth and is often prescribed to treat children who are not developing normally and for adults with muscle-wasting diseases. An increasing number of people obtain the drug illegally to enhance athletic performance, build muscle, and some believe to delay the signs of aging.

The actual number of teens who have experimented with synthetic HGH is thought to be significantly lower than the 11 percent, however. Steve Pasierb, President and CEO of the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids, cautioned that the 11 percent figure includes those who have taken HGH and those who have taken supplements believing they contain the hormone.

Synthetic human growth hormone can only be administered by injection; supplements are taken as orally. Even those supplements that do contain a compound that induces the body to boost HGH production, will have a much smaller effect than injecting because stomach acids greatly reduce the amount of the hormone that will make it into the bloodstream. Pasierb is concerned that 11 percent of children at least believe they are experimenting with the real drug, and may have psychologically taken the next step. “If you’re a committed user, the needle may or may not be a personal barrier,” he said.

Former cyclist Tyler Hamilton agrees with Pasierb’s concerns. Hamilton started doping with erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone that boosts red blood cell production and moved on to HGH. “I knew I’d crossed the line, but I didn’t know how far I’d go,” he said about the first time he was given a large red pill to take by his team doctor. “Having already made the decision with the testosterone pill, the needle felt like the only way.”

Hamilton served a two-year ban by the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) after failing drug tests in 2004, and was given an eight-year ban by the USADA for testing positive again in 2008. He admitted his own drug use in 2011 and returned the gold medal he had won in the time trial at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. He now gives talks at high schools and universities about his performance enhancing drug use, hoping that by hearing his story, students won’t make the same mistakes he did.

The survey announced this week did not specifically focus on children who may be taking the drug for an athletic advantage. William Raikes, Assistant Director of Consumer Research for the Partnership for Drug-Free Kids, says that because the high number of children reporting they had used HGH was unexpected, the study had not investigated the trend in further detail. Future surveys will explore HGH use in greater depth, including determining whether it was used in the hopes of improving athletic performance.