Mo'ne Davis, Taney take center stage at Little League World Series

A girl throwing perfect spirals in the outfield: This is how the story of Mo’ne begins, and by now, Steve Bandura has told it countless times. It was an autumn Sunday in Philadelphia’s Graduate Hospital neighborhood, the sun fading and night closing fast. Bandura, a local youth league coach, was on a tractor, grooming a baseball field after a game, when he noticed a girl throwing a football to a group of boys in the outfield. He introduced himself and invited the girl to a basketball practice later that week.

"It’s all boys, if you don’t mind," Bandura told her.

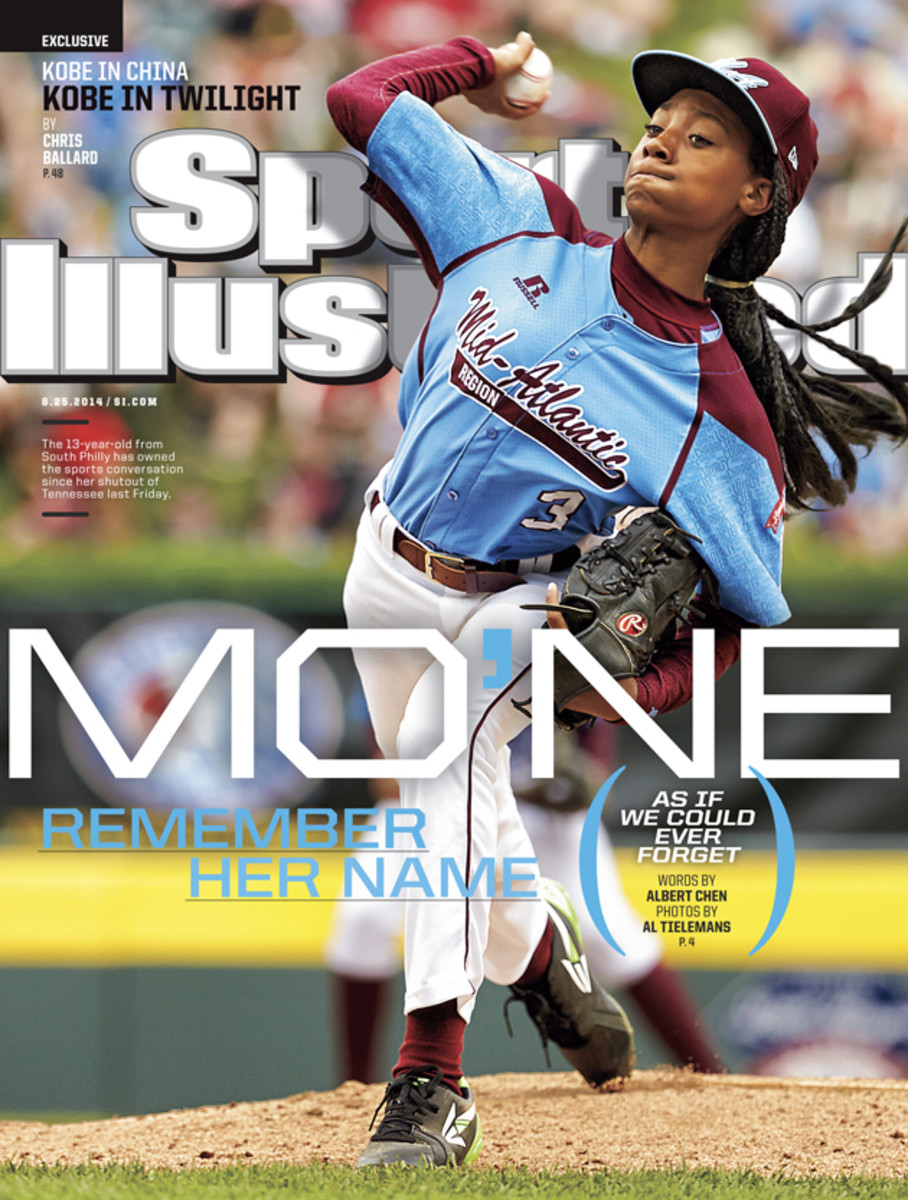

Mo’ne Davis on this week’s national Sports Illustrated cover

A girl throwing perfect spirals in the outfield: Anyone who’s been following The Mo'ne Davis Story at this year’s Little League Series has heard the tale. Someday, they’ll tell the story at a WNBA awards ceremony, or maybe in Cooperstown. But now, when Bandura looks back, that part of the story of how he met Mo'ne Davis, then seven years old, wasn’t really the amazing part. The amazing part was what happened two days later: The girl showed up to the basketball practice.

"I never thought I’d see her again," he said.

It was Sunday night here, and Bandura was walking up the hill toward Lamade Stadium as he told the story. "We were in the middle of doing three-man weaves, and she walks in, with her mom," Bandura said. "Mo’ne put her stuff down and got in line. This isn’t an easy drill, and we had been practicing and practicing, and finally had it down. She got in line, and I said, 'You don’t have to do this, they’ve been practicing this for a while.' She shrugs and says, 'No, I’ll try it.'

"She was third in line, two groups in front of her went, and I could see her studying, her eyes processing, moving back and forth, following it the whole way," Bandura said. "Her turn came, and it looked like she had been doing it her whole life. I knew right then that this was someone special.”

You probably know what happened next. Bandura had Mo’ne join the baseball team — she’d never picked up a glove in her life — and the rest is history. Now Mo’ne is a national phenomenon, on the cover of this week’s Sports Illustrated. But the story of the Taney Little League team is much more than a story of its 13-year-old prodigy. It is also about inner-city baseball, the challenges it faces, and how — even in this age of AAU and travel baseball, Versailles-like Little League complexes in the suburbs that city leagues can’t compete with and early specialization in youth sports — it can still triumph.

GALLERY: SI's best shots of Mo'ne Davis at the LLWS

Unlike suburban little leagues, the Taney league doesn’t own any fields. It doesn't make money off any concession stands, it doesn't have a main clubhouse where the kids can convene, it doesn't even have an address. Instead, it rents a post office box that someone checks once a week. Fields, most of them poorly maintained, are scattered across the city and squeezed into narrow city blocks, few with any parking.

Two years ago, the league drew from 52 different zip codes across the city, from the heart of Center City to west and south Philly, where some of the city’s poorest neighborhoods are located. To get to fields that are scattered across the city, from Italian market neighborhoods in south Philly where Rocky was filmed to Taney’s main field across the Schuylkill River from the University of Pennsylvania's athletic fields, parents shuttle back and forth on city buses, or car pool, or walk, or bike through the streets.

"You hear that baseball is becoming more and more limited, losing kids to soccer or lacrosse, where they may get scholarships," said Ellen Siegel, one of the five founding members of the Taney Little League. "But we’re seeing the opposite. We can’t keep up with the number of teams." Ten years ago Taney had 36 teams; this year, it had 73. "And I can’t imagine what it’s going to be like next year," Siegel said. "People are already contacting me saying, 'How do I get my kid signed up?'"

Siegel received a breathless call from one mother last week after the Dragons won the Mid-Atlantic regional title to advance to Williamsport. "I want to sign up my kid, but I might be a tiny bit early," she said.

"How old is your kid?" Siegel asked.

"Three," the mom responded.

From day one, the league’s priority has always been on inclusion — "The mission is to do everything we can to get kids playing," Siegel said — and the league keeps fees affordable, with financial aid and an equipment sharing program available to families. It has been a co-ed league since its inception. Taney added a softball league a few years ago, but as Siegel said, "We’ve always been focused on girls playing hardball all the way through." Two decades before Mo'ne, the league’s first yearbook included an advertisement from the National Organization of Women: "Taney Baseball — Where Girls Play Too."

As it is dying in cities across the country, youth baseball is thriving in Philadelphia because of the passion of people like Siegel, Taney head coach Alex Rice, the players' parents and Bandura, whose program is at the core of Taney’s success — Bandura coached seven of Taney's 12 players from the time they were six and seven years old. In 1995, Bandura was a volunteer at the Marian Anderson Recreation Center when he started the Anderson Monarchs, a program for inner-city kids to play baseball, basketball and soccer year-round. On an empty field in the middle of a desolate block in the Graduate Hospital neighborhood, he broke ground on a field that has, with the support of local donors, evolved into the jewel of youth baseball in the city, with a mound, an on-deck circle and an outfield fence covered with local advertising,

Inside the rec center next to the field, in a dimly-lit, low-slung room that used to be a girls locker room, there are batting cages. The boys' locker room is now a weight room. Throughout the training areas are inspirational quotes from John Wooden, Chuck Knox, Bobby Knight and painter Edward Simmons ("The difference between failure and success is doing a thing nearly right and doing it exactly right.") This is where many of the Taney league players learned the game, from Bandura’s son, Scott, the team’s catcher, to Davis, who has been with the Monarchs since she was seven. After Taney obtained a Little League charter in 2012, making it eligible for the Little League World Series, Bandura encouraged his top players to play for Taney in addition to the Monarchs.

In a room behind the cages, you’ll find shoebox sized lockers with the names of the seven Monarchs players on the Taney team: Davis; Scott Bandura; Jared Sprague-Lott, who hit a big home run in Taney's first win in Williamsport; Jahli Hendricks, who hit a three-run home run in a key game in the Mid-Atlantic Regionals; Carter Davis, who hit an RBI sac fly in last week’s win over South Nashville; Zion Spearman, the irrepressible outfielder who says that before he was clutch, he was just bad; and Jack Rice, the manager’s son and shortstop who cut his mouth and felt dizzy after a hard tag in the head on Sunday, and was back practicing the next day.

CORCORAN: Angels grab first in AL West, but for how long?

Mo'ne is the star pitcher, of course, though she can play many positions. And her baseball story isn’t possible without Bandura, who soon after meeting her encouraged Mo'ne to apply to Springside Chestnut Academy, one of the top private schools in Philadelphia. Mo'ne tested in, and five years later, she’s an honor student who makes the hour-plus commute from her home in southwest Philadelphia to the school in the Chestnut Hill neighborhood. After all her practices, she typically doesn’t return home until nearly 7 p.m., sometimes later. A few days a week, she’ll crash with Bandura and his family to save herself the long commute.

"Mo’ne is not only an honor roll student, but she is also the leader," Bandura said. "Everyone looks up to her, even the older girls. And when you see older middle school girls looking up to a younger middle school girl, you know that girl is something. It's unbelievable."

The Importance Of Being Barry: The best player in baseball? Barry Bonds. (Just ask him.)

The legend of Mo'ne began to grow in local neighborhoods as she dominated boys in just every sport she played. She is the center midfielder on the Monarchs' boys soccer team, though her first love is basketball. Her dream, as she's already proclaimed to the world, is to run Geno Auriemma’s offense at UConn. To hear others tell it, she could run the 76ers' offense. "She is phenomenal," said Elliott Hughes-Taylor, a Monarchs coach. "She completely dominated the Philly league here. Every play, matching up with 6-foot-2, 6-3 boys." He added, "Everyone’s seen her pitch. Well, I promise you, she’s five times better at basketball."

GALLERY: When sports starts were in Little League

One night after a basketball game, Bandura asked Mo'ne how the game went. "We won 41-38," she replied.

"How many points did you have?" Bandura asked

"I don’t know."

"About how many?"

"I don’t know."

Later that night, Bandura received a text from the coach. "You missed a great game," it read. "Mo'ne had 35."

"The thing about that story is that she really doesn’t know," Bandura said. "She’s not self-conscious at all. She doesn’t get too high or too low and nothing fazes her, as people are seeing. And she’s all about the team, which is why her teammates love her."

Mo'ne will take the mound Wednesday night in Williamsport against a Las Vegas team that looked like the Detroit Tigers when they clobbered the team from Chicago on Sunday. Taney may lose tonight, and they may lose again later this week, and that may be the end of the story of Taney baseball here in Williamsport.

As for the story of Mo'ne? It’s big. It’s going to get bigger.