First African-American All-Ivy League swimmer found unlikely passion

The self-proclaimed Queen City of the Ozarks, Springfield, Mo., sits deep in the beefy midsection of America. It's no coincidence that Prime Inc. is headquartered there. Just air horn blasts away from both I-44 and where Route 66 was born, Prime is one of the nation's largest trucking concerns, with 6,400 long-haul drivers who can ferry 40-ton loads to either coast in two days.

The headquarters are a cross between corporate office park and world's swankiest truck stop. As drivers await rig repairs or freight, they can luxuriate at Prime's spa or use its library, weight room or basketball court. On a Friday in mid-December, a hundred drivers gather in a common room for a morning meeting. A supervisor congratulates them on an accident-free November, warns about misty conditions on I-70 and commiserates over new regulations that might add to their thicket of paperwork. The drivers—a diverse mix of ages and races, and more women than you might think—pay a level of attention usually reserved for in-flight safety demonstrations.

Their interest spikes, though, when the fleet's fitness coach begins speaking. Wearing a high-wattage smile and a warmup suit that highlights his muscled physique, he evangelizes about self-improvement and health and wellness. Trucking is a profession with one of the highest rates of obesity and lowest life expectancies in the U.S. "I was almost an Olympic swimmer," the trainer says. "That was my dream. What's yours?"

After speaking for 10 minutes, mixing self-help homilies with data about diet and BMI and metabolic rates, he leads a group of drivers into a Prime body shop. With bemused mechanics looking on, the drivers work out over the clanging of tire irons and the hissing of air guns, exhorted by this charismatic Jack LaLanne for the big-rig set, a 43-year-old who could pass for a decade younger. "It doesn't matter if you do this exercise or that exercise," he bellows. "The main thing is that you keep it moving! You want to turn that radio on in your truck and get down? Great! That's exercise!"

The truckers heed the coach, in part, because he is also a colleague. Driving for Prime, he has logged more than 300,000 miles on ribbons of asphalt. He has known sleep-deprived days, double-clutched a 53-footer on a mountain pass and crammed 11 hours (the maximum allowed by law) at the wheel into each 14-hour shift. Thousands of drivers have shed tens of thousands of pounds following his gospel.

It is something to behold: a fitness class of overweight truckers, led by a ripped African-American, himself a longtime driver. The tableau also solves a mystery that, for more than 20 years, vexed many members of the Yale class of 1993, myself included: What the hell happened to Tony Blake?

If you were to make a list of college sports dynasties, Yale swimming would have to be on it. The team's longtime coach, Robert J.H. Kiphuth, won four NCAA championships in 11 years and retired with a dual-meet record of 528--12 and the astronomical winning percentage of .978.

Alas, those NCAA titles came between 1942 and '53. Unable as an Ivy League school to provide athletic scholarships (and unwilling to bend admissions standards in recruiting), the program fell into mediocrity after Kiphuth's retirement in '59. By the 1980s the Bulldogs were lucky to finish in the top half of the Ivy standings.

Hope was renewed, though, as the 1990s began. The recruits for the class of '93 were uncommonly strong, led by Anthony (Tony) Blake. At age 10, around the time he won an Illinois state championship, Blake declared his ambition to make the U.S. Olympic swim team. His distant cousin Hayes Jones had won a gold at the 1964 Tokyo Games in the 110-meter hurdles, and Blake figured, Why not me, too? His next decade comprised a string of successes—including state and regional titles—that suggested his goal was within reach. "Tony Blake was a superstar," says Frank Keefe, Yale's coach from 1978 to 2010. "A superstar."

Blake resisted convention in every conceivable way. For one, he was not from a swimming hotbed such as California or Florida, but rather from Oswego, Ill., where he was raised by his dad, Jerry, after his parents divorced. While his teammates were tall and lanky, classically built for swimming, Blake was 5'8" and 135 pounds. He offset his slight stature with competitive zeal and impeccable technique. Early in his freshman year he was placed in a practice lane behind Andrew Geller, a senior and the team's best swimmer. Frustrated with Geller's pace, the freshman passed the upperclassman, a huge breach of protocol. Geller was furious. Blake shot back, "I don't care who you are, if you aren't going fast enough, I'm going in front of you."

Keefe loved it. "He was this intense kid who was always looking for a challenge," the coach says. "Put him in any situation, anywhere in the world, and he comes out a winner, know what I mean?"

Blake also had a different pigmentation from most of his competitors. When he arrived in New Haven, Conn., no African-American had ever swum in the Olympics. Only two years earlier, Dodgers executive Al Campanis had pontificated on live national television, "Why are black men, or black people, not good swimmers? Because they don't have the buoyancy."

Keefe wanted Blake to focus on the sprint freestyle. Blake resisted. "That was the typical image of the few black swimmers: They only swim the sprint freestyle," he says. "I wanted to prove that I could do it all." Blake compromised; he would swim the 50-, 100- and 200-yard free but also the 100 and 200 breaststroke and—consider this a bit of foreshadowing—the 200 individual medley. He often trained in the distance lanes during practice.

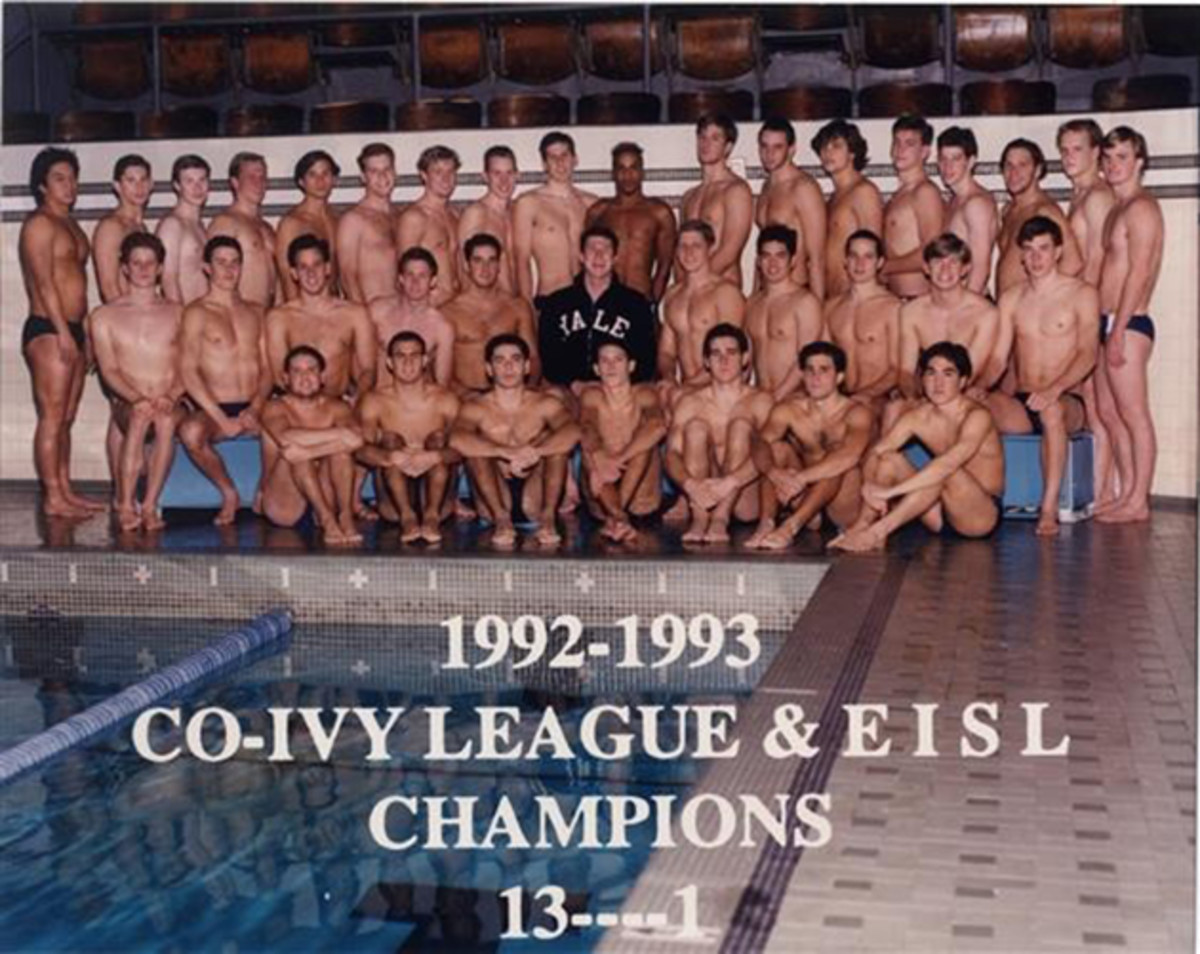

As a sophomore Blake finished fifth in the Eastern Seaboard Championship and became the first African-American swimmer to be named All-Ivy. That season, thanks in no small part to Blake, Yale finished 10--3. His junior year the team was 9--1. Blake's college swimming career culminated in February 1993 when Yale hosted the first meet against both Harvard and Princeton. H-Y-P, as the "three-meet" became known, has become a fixture in college swimming. In '93, though, no one quite knew how the event would go. This much was clear: If the Bulldogs could hold off Princeton, they would win a share of the league title for the first time in 20 years.

The meet was held at Payne Whitney Gymnasium, the second largest gym in the world by cubic feet. While it was—and is—a dark and charmless place, its acoustics are akin to those of a basketball bandbox. During that H-Y-P meet, with 1,500 fans in the stands, the pool was rock-concert loud. Before the final event, the 400 freestyle relay, Yale trailed Princeton by a point. The Bulldogs' lead swimmer: senior Tony Blake.

That Blake was even on the blocks that night was something of an upset. With an eye on the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona, he had entered the '91 U.S. Open Swimming Championships during his junior year. It was, as he puts it, "my last, best shot of ever qualifying for the Olympics." And he swam poorly. In the 100-meter freestyle, Blake says, he missed qualifying by .8 of a second. He was too much of a realist to reset his sights on Atlanta in '96. Right there in that Minneapolis cool-down pool, he tearfully administered last rites to his dream.

Multiple Yale teammates use the same phrase to describe the effect of this defeat on Blake: It destroyed him. Blake doesn't disagree. "I was heartbroken," he says. "This was the first time I wanted to do something and couldn't do it. I just didn't want to swim anymore."

Shortly after that he spent a few days in the psych ward of Yale--New Haven Hospital; a roommate had found him passed out near bottles of pills. Blake says it wasn't an earnest suicide attempt—"more of an academic exercise"—but he wasn't allowed to check out until Keefe came and vouched that Blake wasn't a danger to himself.

At the start of the next season Keefe urged Blake not to quit the team, telling him that he would regret not having seen his college career through. They finally reached an agreement: Blake would stay on the team, but he wouldn't have to attend every practice and train as intensely as he had as an underclassman.

As soon as the starter's gun sounded for H-Y-P's final race, Blake was operating at peak efficiency. He was all complexity and contrasts, and his swimming style was no different: It was at once fierce and graceful. He would thrash the surface, carving it with violent strokes and kicks. Yet viewed from afar, he glided as though the water were his natural habitat.

Payne Whitney decibel levels reached an alltime high as Blake raced to a healthy lead. His teammates didn't relinquish it. By winning the relay, Yale beat the Tigers 123--119 and earned a share of the Ivy League swim title. All those early-morning practices, trudging to the pool and then heading off to class with frozen hair? This was the payoff. The swimmers hugged and shrieked and poured champagne into the water, then swilled the rest. The celebration would continue until the sun came up.

And that was pretty much the last anyone at Yale saw of Tony Blake.

[pagebreak]

When Blake’s name came up those last few months of our senior year, the discussion usually veered in one of two directions. The first centered on the rumors of what had happened to him: a) he was suffering from burnout, hardly uncommon at Yale, where stress, expectation and ambition sometimes alchemized to disastrous effect; b) he had gone to Europe in pursuit of a love interest or a band ("We heard he was roadying for Smashing Pumpkins," says teammate Josh Woodruff); c) in a bit of typical college overreaching, others theorized that the country had just sworn in the first Democratic president (Bill Clinton) since we were in the fourth grade, and Blake's walkabout was a manifestation of a new, free-spirited ethos.

The second, more general, conversation began: Who in his right mind would leave Yale a few months from graduation? Short answer: Tony Blake. "You're talking about a guy who just did things his own way," says Mike Englesbe, a swimmer who was Blake's roommate. "I knew him as well as anyone; but I didn't feel like I totally knew him."

Reflecting on Blake, former teammates and classmates often use the same two phrases: good dude and out there. He and Woodruff once drove to Philadelphia, missed their exit, and decided to keep going until they reached Disney World. Englesbe recalls returning to their off-campus house to find that Blake had painted his room black, to experience sensory deprivation.

As a junior Blake attended a Yale forum on student life. The school's president, Benno Schmidt, spoke vaguely about proposed changes. Blake stood, cut Schmidt off and railed against overcrowding. He complained about being shut out of an underfunded philosophy seminar; about food shortages in the dining hall; about lack of space in the dorms and his consequent exile to annex housing. The crowd broke into applause. Schmidt turned to Blake and replied meekly, "I'm glad you can still smile after all that."

While other students attended faculty office hours to curry favor, Blake, a philosophy major, went to argue points. During his senior year he was assigned a paper on the love of fate for an existentialism class. Instead of explaining the concept, Blake offered his own example: He submitted a paper consisting of two Latin words in big, bold letters, Amor Fati (Love of Fate). "That's embracing fate," he recalls. "I could've gotten an A or I could've gotten an F." (The professor gave him a D, conceding that it was an inspired idea but noting that it was unfair to the other students who had labored over 20 pages.)

As a senior Blake was admitted to a secret society. According to tradition, each member gives a "bio" to the group. Most presentations are casual, involving family trees and high school yearbooks. Blake? He invited the other members to his black-walled room, put on Miles Davis and placed a few pet-store hamsters on an overturned black box on a tabletop. The animals scrambled to the edge of the box but wouldn't jump off. "It was supposed to be performance art," Blake says. "Are there limits to your courage?"

"Kids always wonder, What am I going to do with my life?" says Keefe.

"Well, Tony wasn't going to sit in an office or work nine to five. No chance. Whatever he was going to do with his life, it was going to be his will. It wouldn't be dictated to him."

After helping his teammates win an Ivy title, Blake reckoned, My work here is done. He had been studying Jesus and Buddha and other spiritual luminaries. "I was like, I'm tired of reading about these guys," he says. "All of this is garbage if you don't actually do it. Yale wasn't helping me; it was stifling me. I know people thought I was nuts for leaving when I did, but I didn't want to be there."

So he left. He grabbed a sleeping bag, a stash of clothes and personal items, a loaf of bread and a jar of peanut butter. He said a few brief goodbyes. Englesbe couldn't talk Blake out of leaving, so he did the next best thing. "I remember loaning him a bunch of cash," he recalls. "I haven't seen him since."

Taking buses and hitchhiking, Blake made it back to Illinois. When he told his dad of his plans, such as they were, he wanted to do it face-to-face. He recalls, "I show up on the doorstep: Hey, Dad, I left school. I'm going to travel the world. I don't know when I'll be back, if ever."

"I tried to talk him out of it, because all he had to do was take his exams and he could graduate," says Jerry, then an administrator of information systems for Nicor Gas. "People kept telling me, 'He'll find himself,' but at the time I was upset."

At commencement ceremonies on May 23, 1993, Jodie Foster, who had gotten her Yale degree eight years before, addressed the graduates. "Being twentysomething," she said, is "about being fearless and stupid and dangerous and unfocused and abandoned ... [going] beyond all those neat little unquestioned boxes the world puts in front of you."

Tony Blake was conspicuous in his absence, one of the few students who had entered in the fall of 1989 and were not getting their degree. Where was he that day? "May of 1993," he says, slowing to take inventory. "I was surfing off Huntington Beach."

Blake would spend the next 15 years following his whims. He carried most of his possessions on his back, turtlelike, and circumnavigated the globe, threading his way from Amsterdam to Prague to Trinidad to Honduras to Togo to Ethiopia. There wasn't much of a long-term plan or organizing principle; just a deep sense that life needed to be experienced, yoked to an unshakable belief that it would all work out.

He interrupted his sojourns, however, to handle some unfinished business. In 1995, Blake became the father to a daughter, Sierra Joy, and he figured it was time to get his degree. After taking two classes at Loyola of Chicago while working odd jobs, he returned to New Haven in '96, knowing almost no other students, with no athletic eligibility left. No matter. Though permitted to reenroll, Blake felt as though he couldn't burden his father with more tuition. After paying the bill from his savings he had no funds left for housing. He had recently been in Europe and joined the squatters' movement. He thought, Why don't I try that here? Blake spent the semester living rent-free in abandoned New Haven buildings and eating most of his meals at soup kitchens.

Keefe recalls meeting Blake for lunch that semester and doing a double take when his former star walked into the diner. "He was a Rastafarian," Keefe said. "He said that he wanted to be the national swim coach of Ethiopia. We had a great conversation—with Tony, you always did. But, yeah, he was out there."

Blake graduated, but that did little to change what he calls "my itinerant lifestyle." (His relationship with Sierra Joy, who lived with her mother in Nebraska and is now a college student there, was strained, though he says it has improved lately.) He headed to Chicago and worked for several nonprofit organizations, including the Illinois Public Interest Research Group and the Nkrumah Washington Community Learning Center, in the heart of gang territory. Then, as his 30th birthday approached, he decided to go back to Africa. "I didn't feel like I knew who I was," he says. "I didn't know my history. Like a lot of African-Americans, we don't know our past. All of a sudden connecting with my ancestral heritage became very important."

So he traveled to Ghana, Benin, Togo, South Africa and Ethiopia, using money he had saved, he says, making wood furniture and doing desktop publishing. In South Africa he met with tribal elders. They said that when a son of the soil returns home, a new name is conferred on him. They dubbed him Siphiwe (pronounced seh-PEE-way), a name common among the Xhosa and Zulu tribes. They said it means Gift of the Creator. For a surname, they chose Baleka, an anagram of A. Blake that variously (and appropriately) means fast and he who had escaped.

One offshoot of this change: It became even harder to track the guy down. His former teammates communicated on Listservs and message boards; Siphiwe Baleka eluded them. They did, however, come up with what would later be called a meme: Tony Blake Sightings. One Yale swimmer ran into Blake in Paris; another heard from a mutual friend that he was in Copenhagen; a third thought he saw Blake in San Francisco. "I wondered for so many years what happened to Tony and wanted to know he was O.K.," said Kristin Krebs-Dick, captain of Yale's 1993 women's swim team. "What could he be up to?"

"Those Tony Blake sightings, I was part of those too," says Jerry Blake. "His teammates and friends would let me know what they were hearing. He'd be in Italy. He'd be in France. For a while he had no money and was trading stories for dinner."

In 2008 Baleka was wearying of his chronic shortness of cash. He knew he wasn't cut out for a corporate job. "I had a Yale degree, but my résumé was"—he laughs while groping for a euphemism—"nontraditional." A truck-driver friend made a suggestion. Drive a truck. It suits your nomadic lifestyle. You got plenty of time to think, and you can save a lot of money.

Always game for adventure, Baleka traveled to southern Missouri and joined the Prime fleet. He obtained his commercial driver's license, made a series of trips over four to five months with an instructor-driver and eventually became a lease operator. (Trucker locution for, He got his own truck.)

Soon he'd been to each of the 48 lower states, living a life pinched from anthem lyrics. Under spacious skies, through amber waves of grain, he drove from sea to shining sea; from the dawn's early light to the twilight's last gleaming; from the redwood forest to the Gulf Stream waters. Sometimes he'd haul steaks; other times, pharmaceuticals. Sometimes he'd head to the dock in Seattle; other times, to the port of Miami.

Driving the rig began to feel as natural as driving a minivan. The job fed something in him. The roads represented a wilderness, each trip a unique adventure. He loved the unpredictability, the movement, the solitude—only his thoughts riding shotgun. He listened to a book a week on his Kindle and, through an audio program, taught himself to speak Zulu. "Sometimes you're singing songs, you're thinking about the future, whatever," he says. "It so suited my temperament."

And driving triggered a feeling of familiarity. Baleka hadn't been in a pool since he'd left Yale, but here he was maneuvering in a lane, reaching a destination and then returning in the opposite lane; getting lost inside his head; feeling a sense of autonomy as he paced himself. The parallels between driving and swimming were unmistakable. He also saw in the job an element of public service. So many of our possessions—clothes, food, furniture—come, literally, off the back of a truck. "You realize you're a vital part of the economy," says Baleka. "You might not get the respect or recognition, but, man, without truck drivers, this country doesn't run."

What he liked less: the changing contours of his body. In less than a month on the job, he went from 140 to 155 pounds. Flat abs turned into love handles. Unapologetically vain, Baleka was rattled. "As a swimmer, you have this toned, athletic body," he says. "You spend most of your time in a little skimpy swimming suit, so you either look good or you're embarrassed because you don't look good."

Some of his weight gain was due to the sedentary nature of the job and to the truckers' inability to prepare their own food. Then there were the effects of what Baleka calls "the truckers' grid." When you're assigned to maneuver a steel whale measuring 50-plus feet and weighing as much as 80,000 pounds with cargo, you stay mostly on interstates. You don't drive to the precious parts of town where markets sell grass-fed meat and organic fruits and vegetables. But by "hacking my own metabolism," as Baleka puts it, he diagnosed the principal cause of his new girth: the schedule. The freight dictates whether truckers drive by night or by day. Many drivers struggle to get more than four hours of uninterrupted sleep. "Sleep deprivation accumulates every day, every week, every month, every year that you drive," Baleka says. "The hormones that regulate metabolism are produced in your sleep. When this production cycle is constantly changing and constantly interrupted, you're not able to produce the hormones properly. So your metabolism changes."

Not only his body but also his mood were affected by the weight gain. Baleka realized he had to make a change. He began by doing push-ups and sit-ups at rest-area gazebos; sometimes he'd make an exercise mat out of a cardboard box and place it beside his rig at a truck stop. He tried the workout programs P90x and GSP Rushfit. He tried resistance equipment and kettle bells and sandbags. He bought a fold-up mountain bike and rested it against the passenger seat in his cab. He bought a YMCA membership that entitled him to use any facility. He'd figure out the timing and call ahead. "Is there anywhere to park a truck?" he'd ask the nearest Y. "No, not a pickup truck, a semi truck. O.K., I'll be by."

He also realized that he could use the job to his advantage. "I'd be driving through Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and I'd see the mountains. I was like, Man, I want to go rock climbing, I want to go mountain biking. I might be in California or Florida; I want to go surfing. Or it was wintertime, I'd be in Pennsylvania or Wisconsin. I want to go snowboarding. I might see a lake. O.K., I'm going to swim across it. Why not?"

Pretty soon the weight vanished, tight abs supplanted the love handles and Baleka reached this conclusion: He could drive a truck and still be a competitive athlete. He hadn't been in a pool in 18 years, but in 2011, at 40, he entered a U.S. Masters swimming meet, the Ball State New Year's Resolution event. He won the 100-yard IM, thus qualifying for the Masters Nationals in Arizona. He figured he would enter. He took first in the 50 and the 100 freestyles in 22 flat and 48.4 seconds, respectively.

Two decades after failing to make the U.S. Olympic team, he was a national champion.

The CB radio may be a cultural artifact—trucking's equivalent of the firefighters' pole—but Baleka found ways to interact with other drivers. He fit in easily, happy to talk shop with colleagues. Details of his backstory leaked in spurts, but Baleka didn't dwell in the past. On the rare occasion other drivers asked about college, he would say vaguely, "Oh, that was in Connecticut a long time ago."

But when the conversation pivoted to health and fitness, he was outspoken in the extreme, commiserating, giving tips and then rattling off statistics, some of which are in dispute. According to Baleka, the average life expectancy for a long-haul truck driver in the U.S. is 61 to 64 years (10 to 15 years less than the average American male); truck drivers have the highest rate of obesity of any occupation in the U.S. (86% are overweight, 69% are obese); they have one of the highest rates of metabolic syndrome, a group of risk factors for heart disease and diabetes; in some years they have had the highest number of fatalities of any occupation, making trucking one of the most dangerous and unhealthy occupations in the U.S.

At the start of 2012, Baleka went to Prime's founder and president, Robert Low, with a business proposal. What if he gave up driving and became an in-house fitness coach, devoting his time to getting the fleet healthier? Low was all for it. "Truck drivers should not have to sacrifice years off their life span because they drive trucks," he says. "We are investing capital and human resources in our drivers' health."

For all of Baleka's spirituality and for all the time he spent in philosophy classes and the nonprofit sector, he is fiercely rational and capitalistic in his approach to fitness counseling. He explained to Low that lowering health costs would help Prime's balance sheets. As for the drivers, he says, "They will go for whatever is going to make them more money and help them feed their families. Healthier drivers get to drive more, which lets them earn more money."

He's aware of his shift—the free spirit turned entrepreneur—and makes no apologies. "At first I had this perception that money was the root of all evil," he says. "Then I saw how much money was needed by people I was working with and how much money I needed to do the projects I envisioned. I think money with no purpose can be dangerous. Once I had a purpose, making money was a necessity."

To that end, Baleka set up a free 13-week Prime Transformation program, with two components: nutrition and exercise. Using smartphone apps as well as equipment provided by Prime, drivers track everything from their biometrics to their quality of sleep. Baleka monitors the data and makes suggestions. The goal is to do at least four minutes of vigorous exercise a day and reduce carb consumption. "Do that, and it's hard not to lose a pound a week," he says.

At the end of 2012 James Peters, 39, a 5'11" Native American driver, weighed close to 340 pounds, with a body-mass index of 47.4. When he signed up for Baleka's program in May 2013, Baleka asked him why he was there. "For my family," Peters said. "My wife is disabled. As heavy as I am, I could have a stroke or a heart attack. What would happen?"

The first step was to change his eating habits. The fast food and the buffets and ramen noodles were replaced by five to seven small meals a day. Then Peters began adopting some of Baleka's fitness plans, devoting 20 or 30 minutes of each day to exercises such as interval training and jumping rope. "He's that little voice, that motivator pushing you in the right direction," says Peters, now down to 227 pounds, with a BMI of 31.7. "He made it all work for me."

Baleka also started a pet project: developing what he calls a "fatigue-a-lyzer." This Breathalyzer-style product would access digital health technology to determine driver fitness based on fatigue. The current federal limitations on driving time are 11 hours in a 24-hour period. "But one driver can get eight hours of sleep and still be fatigued, and another can get four hours of sleep and be fine to keep going," says Baleka. "We have these diagnostics for the tractor and trailer: rpm, speed, hard breaks. The one thing we don't have real-time data on is the most important—driver physiology."

By this time Baleka had started competing in triathlons. He read a training manual on the road and was hooked. He entered a sprint event in Muncie, Ind., in 2011 and finished among the top three in his age group. Then he moved on to Olympic distances. "I did about eight of those in 2011," he says casually.

Then, in an act of amor fati, he began training for an Ironman triathlon. Figuring that he might as well race somewhere meaningful, he entered Ironman South Africa and took most of his family on the trip to Port Elizabeth: his dad and his sister; his son, TaNihisi, now three; and his then wife and her four sons. (He has another son, TaMeri, five months old, by his ex-wife.) On race day he swam the 2.4 miles in a storm and left the water in the top 50. He finished the Ironman in less than 12 hours, placing 214th out of nearly 1,400 competitors. "I felt like my ancestors were there," he says. "It brought everything together: my trucking life, my sporting life, my spiritual life, my family life."

Jerry Blake was waiting for his son at the finish line. Jerry says, "You know how people told me, 'He'll find himself'? Well, he did."

Meanwhile Baleka branched out to help drivers from other fleets, who can use his system through Fitness Trucking, the consulting company he started. He is a columnist for two trucking magazines, speaks at workshops, tests digital health equipment and sports equipment and makes recommendations to trucking firms. "I want to revolutionize this industry," he says. "I want to make the unhealthiest occupation one of the healthiest." And then?

"I'm sure there will be another quest, but right now, I'm here," Baleka says, surveying the truck yard. "I'm not going anywhere anytime soon. Can you believe I just said that?