Want to avoid injury? NBA teams are looking to Marcus Elliott for answers

This article appears in the Dec. 29 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

In general, sports analytics focus on what has already happened. SportVu cameras track every NBA player’s in-game movement. Inertial sensors embedded in NFL practice jerseys track acceleration. Meanwhile, caffeine-fueled young men in front offices across the land race to crunch the data in hopes of gaining their employers an edge.

But what if instead of using information to react to what’s happened, you could use it to make predictions? And what if, in a league such as the NBA, in which success is determined by a handful of freakishly talented $20 million-a-year athletes, you could make the most valuable prediction of all: Who might get hurt, and why?

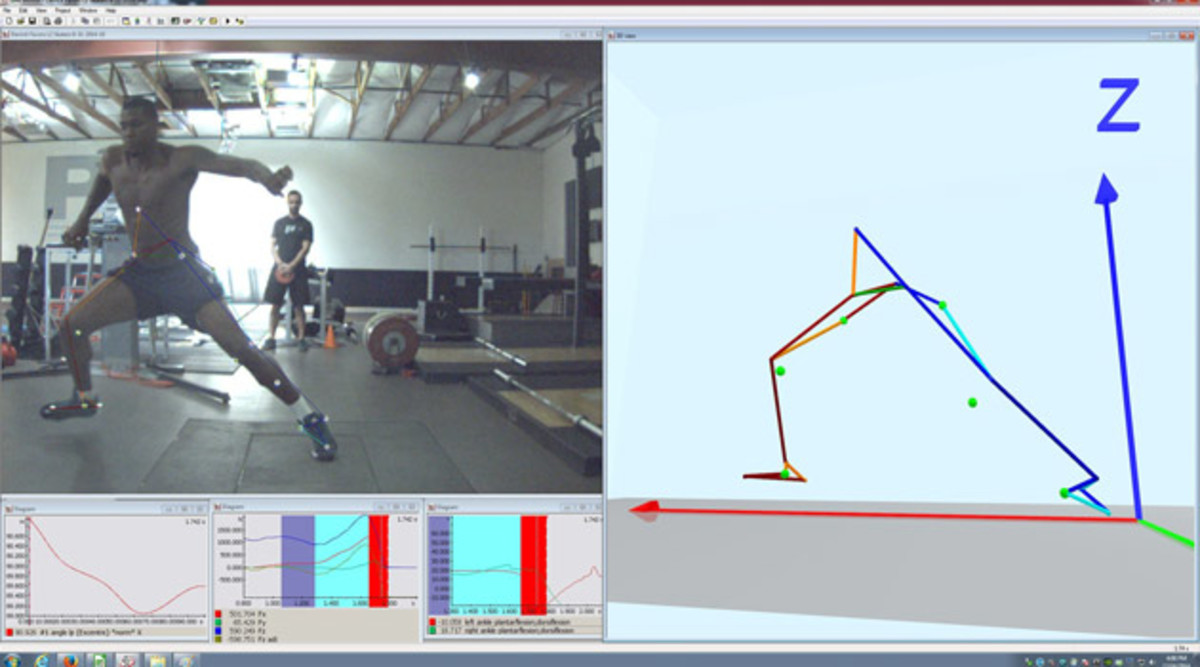

About 15 months ago an NBA team flew a very good young player -- let’s call him Clark -- to Peak Performance Project (P3), a training center and research lab in Santa Barbara, Calif. Clark stripped down to shoes and performance shorts while a bearded Stanford biomechanics grad affixed reflective markers to 22 spots on his shoes, ankles, legs, back and torso. Then, over the course of an hour, Clark jumped and balanced and hopped on a pair of force plates while 10 3-D motion-capture cameras rolled, accruing more than 5,000 data points. Once processed, this raw data became an animated version of Clark’s skeleton as it landed, flexed and ascended. Laid bare, you could see how Clark’s body moved, where it generated power, where asymmetries existed and -- if you knew what to look for -- where it was at risk for injury.

With Clark there was reason for concern. He demonstrated knee-dominant movement strategies, poor active dorsiflexion and tight anterior hip musculature. Basically, bad jumping form. This had led to a left knee injury that had nagged Clark for months. As a result he was unconsciously avoiding his left side and placing a heavy -- and dangerous -- load on his right leg with every jump shot and rebound. If left untreated, P3 concluded, this imbalance put Clark at a heightened risk for serious and chronic injuries on his right side.

How I compare to an NBA point guard

Given this information, some teams might have told Clark to do extra strength work; others might have deemed it too speculative. This team? It modified Clark’s training regimen, de‑emphasizing basketball work for much of training camp and focusing on prescriptive exercises, according to P3. Six weeks later Clark’s imbalance had improved dramatically. He went on to have the best season of his career, and his team made the playoffs. A year later the asymmetry had all but vanished. This season he continues to thrive.

Granted, there’s no way to determine causality. Would Clark have blown out his knee if he hadn’t gone through this analysis and training? Maybe, maybe not. The question, if you’re a general manager, agent or player, is whether that’s a risk you’re willing to take.

Welcome to the next frontier in sports information: predictive injury analysis. As recently as five years ago no NBA team had a sports scientist on staff. Now a half-dozen do, though some go by different titles, and many of those hires occurred in the last year. One club even posted a job listing on LinkedIn.

While teams scramble to catch up, the technology raises thorny questions about who owns such data and how it should be used. Meanwhile, for the players and the franchises that have embraced it, the field of injury prevention offers a potentially sizable competitive advantage. “Remember when the Suns were looked at as being avant-garde because of their trainers?” says one Western Conference general manager, referring to Phoenix’s vaunted staff in the 2000s, which was credited with prolonging the careers of Grant Hill and Shaquille O’Neal. “This is way, way out there beyond that. You’re taking action to correct issues, not just noting them.”

It is a Monday morning in November, and P3 is bustling. Located on a side street a few blocks from the beach in Santa Barbara, a sleepy community where tourist families trundle surfside on four-person bikes and everyone, it seems, lives well, P3 occupies an innocuous white building that was once a live music venue. (The deejay booth is now an open-air office.) Though it has 10 employees, including trainers and biomechanists and data analysts, for many years P3 was essentially a one-man show. That man, a Harvard-trained doctor named Marcus Elliott, arrives a little after 10, having spent two hours catching waves off a local break. At 49, Elliott is tan and athletic, with perfectly mussed brown hair, calling to mind Dennis Quaid in surfer-dad mode. He wears running shoes, black sweatpants and a black zip-up P3 Lycra top.

Upon entering, Elliott checks in with a trio of major league baseball players on hand for offseason workouts. Under Elliott’s guidance, P3 has become a destination for many of the country’s elite athletes. In addition to baseball and Major League Soccer pros, scores of NBA players, including Dwight Howard, Al Jefferson, Kyle -Korver and Andrew Wiggins, have used the facility, and last spring P3 partnered with the NBA to assess prospects before the 2014 draft. The athletes who make the trek to Santa Barbara come for a host of reasons, but two in particular: to improve their performance—to get quicker, stronger, more efficient—and to prolong their careers.

Take Jefferson, the 6' 10" Hornets power forward. He first went to P3 in the summer of 2010, before his seventh year in the NBA, for which he had been traded to the Jazz. When the P3 techs got done examining him, the results were troubling. Every time they loaded his right knee, it would buckle inward. It was, Elliott says, a classic example of an ACL tear waiting to happen. Jefferson had already suffered a right ACL injury, a year and a half earlier. The potential for another tear, Elliott warned the Jazz, remained. Jefferson was at high risk.

That season Jefferson performed corrective exercises and stayed injury-free. (According to P3, some imbalances can be fixed in a couple of weeks; others take months.) The following year, during the NBA lockout, he returned to P3 for nearly six months. By training camp his body had changed. Before, the angle of his right knee had been two standard deviations higher than the average, which meant Jefferson was “at super-high risk to blow out the knee,” Elliott said. “Now his valgus” -- his inward angle -- “is like two degrees, or a little bit worse than our mean, which means there’s a very small chance he’ll have an injury.”

SI's 10 favorite NBA moments of 2014

Most players arrive at P3 without Jefferson’s injury history. On this morning Elliott heads to the back of the gym, where the day’s only NBA client, Patty Mills, looks remarkably comfortable for a man wearing only underpants and shoes. Mills, a reserve guard for the Spurs, is 18 weeks into his rehab from a right shoulder injury. He’s here for an initial assessment, accompanied by San Antonio’s director of rehabilitation, Marilyn Adams.

Over the next 20 minutes Mills details his injury history, sits for body measurements and runs through a series of funky-looking warmup drills: heel walks, leg swings, ankle flexions, rubber-band slides, speed hops. Once he’s loose, he heads to a corner where a large patch of black rubber flooring is flanked by a desk heavy with monitors. Under the direction of three P3 techs, Mills performs a series of tests, taking off and landing on two force plates embedded in the floor. Some of the tests are basic, such as a standing vertical jump. Others are meant to more closely mimic basketball movements: Step off an 18-inch-high box, land on the force plates and leap as high as possible, arms extended, as if going back up for a rebound. Mills performs “one-off skaters,” named for their resemblance to the action of an ice skater pushing off, one leg firing sideways. He reacts to visual cues (a baseball being dropped) to test his reactive movements. Everything is recorded by a host of German-made digital video cameras -- on the wall, on a stanchion above, at ground level.

Off to one side, Elliott and the P3 techs observe and speak in biomechanics jargon, a language of Newtons, deltas and standard deviations. Their goal is twofold. First, to measure Mills’s physical system: how much force he creates laterally, where his vertical power comes from, how quickly he moves in the lateral plane, the angle of his hip extension. Second, to search for asymmetries and red flags. “We look for predisposing factors the same way doctors do in traditional medicine, only instead of heart-attack risk we’re looking at performance risk,” Elliott says. “It’s not rocket science. In a few years every team will be doing this.”

What P3 does is not unique. Dynamic Athletic Research Institute (DARI) also uses motion capture. So does Catapult, the Australian company that popularized the inertial sensors used by many NFL and NBA teams and other pro athletes around the world. Meanwhile, more and more teams and performance centers are investing in force plates and 3-D motion-capture systems. P3’s advantage lies in its hard drives. The company has assessed more than 100 NBA, 120 MLB and 100 other pro and Olympic athletes, from tennis players to cyclists. What’s more, many are tested repeatedly, over a period of years. This gives P3 the most valuable commodity in analytics: context.

P3 can tell a new client, such as Mills, how he stacks up against other NBA point guards in various metrics. It can also look for trends and correlations. Land and jump using mainly your knees, and P3 can warn you that it has found a potential correlation between how deep athletes bend their hips and the occurrence of lower-back injuries.

With every NBA player who comes into P3 and with every new partnership -- testing at Adidas Nations high school camps last summer, for example, gave P3 data on 7-foot future lottery pick Thon Maker and dozens of other top prospects -- the database grows. For Elliott, this is exciting. He envisions studies, papers, breakthroughs. He sees the future unfolding, if only he can keep up.

Elliott is both a likely and unlikely candidate to be at the forefront of sports performance study. The son of a granite sculptor (his dad, Gaius) and a cellist turned homemaker (his mom, Rochelle), he spent his childhood in Stinson Beach, a bohemian northern California coastal town, and then on a 600-acre ranch in Preston, a hamlet north of Santa Rosa. In his telling, he regularly skipped school yet excelled on standardized tests. At 17, he asked for a subscription to the journal Medicine & Science in Sport & Exercise for Christmas. A three-sport athlete at Cloverdale High, he dreamed of college athletic scholarships until he tore up his right knee -- ACL, PCL, the works -- at football practice his junior year.

Why so many injuries in the NBA? Be surprised there aren't more

Elliott had always been interested in performance. Now he was also interested in how the body breaks and heals. He says that after college, first at UCSB and then at Harvard, he competed in triathlons, winning a few midsize races, getting sponsored by Nike and taking in enough prize money to float his training and travel.

Then, at 25, Elliott enrolled at Harvard Medical School. While there he approached Bert Zarins, a professor and the Patriots’ team doctor, and said he wanted to study how and why NFL players got injured. Zarins says he was impressed by the “very smart and very goal-oriented” young man. So, with Zarins brokering access, Elliott analyzed a 10-year data set of NFL injuries, focusing on hamstring issues, which had bedeviled the Pats. He and Zarins also tested New England players during the 1999 season, then created individualized programs to help reduce soft-tissue injuries. As a result, Elliott says, hamstring injuries dropped to three per season from a mean of 21.5 over the previous five years.

At the time Elliott was shocked that elite training appeared so unscientific. This was the era of “no pain, no gain” and heavy lifting. So while his fellow Harvard grads pursued hospital residencies, Elliott carved his own path in exercise physiology. At first he was, in his words, a “really overqualified personal trainer.” Then, in 2006, he opened P3 and worked with his first NBA player, Rafael Araújo. The 6' 11" Jazz center was a marginal pro, big and slow, but under Elliott he became less slow. Araújo didn’t last in the league, but Elliott’s influence nonetheless caught the eye of Utah player development assistant coach Mark McKown. The next year the Jazz sent Ronnie Brewer and Paul Millsap to P3. Soon, at coach Jerry Sloan’s urging, the whole team was flying to Santa Barbara.

In the years that followed, more players and teams contacted P3. In 2010 the Seattle Mariners hired Elliott as their director of sport science and performance. In the NBA the Hawks got on board. So did the Spurs. Korver says opposing players began asking him about P3, sometimes during games. In ’12 agent Bill Duffy negotiated an exclusive deal for his clients to train at P3 before the draft. Last summer Wiggins, Zach LaVine, Aaron Gordon and a half-dozen other Duffy clients spent six weeks in Santa Barbara. (It was then that photos of Wiggins’s standing vertical leap test, in which he reached 12' 4", went viral.)

Sending a pro athlete to P3 is pricey -- $5,000 a week for an NBA player -- but to Duffy the investment is a no-brainer. “You can extend your career by three to five years at that place,” he says. “They address every ailment.”

This is not to say that NBA athletes necessarily understand P3’s process. Many are like Utah forward Derrick Favors, an emerging All-Star-level player who at 23 has already been going to P3 for almost four years. In that time he has improved his lateral movement in particular, posting the highest lateral force of any NBA player tested at P3 (1,314 Newtons, if you must know). This not only puts Favors in the top tier of lateral movers among tested NBA big men but also rates him above average for all positions -- an unlikely achievement for a 6' 10" man who weighs 262 pounds. Favors believes he’s now more effective when he has to switch onto a guard in the pick-and-roll. He says his core is also stronger, and he’s smarter about avoiding injury. “I don’t know how they do it -- it’s scientific stuff,” Favors says. “It’s crazy, but it works.”

At the more inquisitive end of the spectrum is Korver, the Hawks’ 6' 7" sharpshooter and one of Elliott’s most devoted NBA clients. When Korver arrived at P3 in 2008, the initial assessment zeroed in on his left knee. It had troubled him for years. “When I looked at myself on the camera and they showed how I loaded and jumped, I almost threw up,” says Korver. “My left knee bent and almost knocked into my right knee.” He thought, I’ve done that every time I’ve shot a jump shot, thousands of times. The prescriptive work wasn’t easy. “I had to totally reprogram my body,” Korver says. “I was putting all the pressure on my knees, not using my glutes.” Slowly he learned how to leap differently.

There was another problem, though: Korver has unusually long legs, making it difficult for him to get low. So Elliott focused on increasing Korver’s lateral quickness, as he has with Favors. Now Korver’s “rate of force development is 30% faster,” Elliott says, “so he creates space he couldn’t create before.” Korver believes his work at P3 is responsible for his unusual career trajectory. At 33, an age at which most NBA athletes are in decline, he is putting up the best numbers of his career for the second straight season, as measured by both traditional and advanced stats, shooting 54.1% on three-pointers through last Friday. “My body feels better now than it did at 23,” Korver says, “and that doesn’t happen in pro sports.”

More than most other athletes, Korver has bought into the entire Elliott ethos. He even purchased a house in Santa Barbara so he can spend offseasons training at P3. Then Elliott introduced him to the Misogi Challenge, a Japanese purification ritual whose goal, in Elliott’s adaptation, is to test one’s limits. Elliott would perform each challenge with Korver, setting only two conditions: 1) that the challenge carry a roughly 50% chance of failure, for it’s in the struggle that you learn about yourself; and 2) that they not try something that could kill them.

In their first challenge, the summer of 2013, Elliott, Korver and two friends paddleboarded standing up for 27 miles, from the Channel Islands to Santa Barbara. It took 10 hours, and they returned dehydrated and exhausted. Then, last summer, they came up with a new idea: to carry an 80-pound rock three miles. Underwater. So the four men and a writer from Outside magazine took a boat out toward the Channel Islands and, in depths ranging from eight to 15 feet, took turns diving, picking up the rock and walking with it. Sometimes they made it 20 feet. Sometimes all they could do was give the rock a good push. It took five hours, but they succeeded.

It’s a little before noon, and Mills is finishing up. “When we’re done analyzing the data, we’re going to know everything about you,” Elliott tells him, smiling. “And then you’ll see it improve, when you come back in two years, three years, 10 years.”

Mills, 26, is pleasantly surprised: “Ten years?”

Elliott nods, confident. “Ten years.”

This is how Elliott spends a good chunk of his time: selling athletes, teams and others on the benefits of his technology. Charismatic and self-deprecating, he speaks at times in grandiose terms. He’s also a P3 subject; he undergoes an abbreviated assessment every Tuesday, monitoring a stiff shoulder and an unstable hip, the latter the result of an old snowboarding injury.

Down the road Elliott envisions all kinds of applications for P3’s technology. He dreams of licensing the company’s software to teams, which could test players and upload the information to P3’s servers with names wiped clean, allowing for a constant stream of context for the teams -- and a cornucopia of data for P3 to study. Meanwhile, the company has a second facility for development; P3 staff is working on an in-home assessment system, using the Xbox Kinect 2.0, that can provide basic fitness breakdowns.

All the while, the techs sift through the data. When I visited, lead biomechanist Erik Leidersdorf was giving one of P3’s biweekly staff presentations, a PowerPoint examining injury correlation among reactive jumping styles. To many questions he answered, “We don’t know yet.”

Therein lies the risk, and potential, of an emerging field: A lot is still based on faith and conjecture. And just because an athlete is assessed by and trains with P3 doesn’t mean he’s immune to injury. Favors recently suffered a sprained ankle. Jefferson and Korver have been sidelined by minor injuries in the last three full seasons, playing an average of 70.7 and 70 games, respectively. Gordon, who trained with P3 last summer, broke a bone in his left foot in November and is probably out for the season. Which is to say, P3 doesn’t promise invulnerability. Rather, like everything in analytics, it strives to improve the odds.

Some GMs remain wary. They’d prefer to keep their information in-house, even if it means they have to accrue data incrementally, with each new player, D-League signee and visiting draft prospect. Then there is the larger question of where this is all going. “How much information do you have that you can make reliable judgments off of?” asks one Western Conference GM. “There are tons of guys in the NBA who, if you took an MRI of their knees, doctors would say, Whoa! It’s shredded. And they’ll have been playing on it for seven years.”

Others have a hard time separating marketing from results. “I’m not sure the technology is differential,” says one GM who’s chosen to go his own route. An Eastern Conference GM says, “I could easily imagine there being something of use [in] measuring small imbalances that are imperceptible to the naked eye, but there were other things that were all the rage a few years ago, and we’ve moved on.”

This hasn’t stopped some teams from entering the arena. Jazz GM Dennis Lindsey, formerly of the Spurs, says he views P3 as “a very strategic, close partner.” And of course the Spurs undertake nothing lightly.

Which brings us to the NBA itself. After following P3 for a few years, people within NBA operations saw an opportunity. Protecting the health of the players would be good for the quality of the game and for league-player relations. And, naturally, every extra season that LeBron James or Kobe Bryant plays is worth tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars to the NBA.

So this year the league invited P3 to the predraft combine in Chicago. Dozens of the top NBA prospects detoured from the traditional vertical leap and bench press tests to duck into P3’s makeshift lab, separated by a curtain from the main floor. The results provided a far more complete picture of the players’ physical strengths and weaknesses than traditional static tests. Take the vertical leap. “We’ll have athletes who jump really high, but everything comes from hip extension, so when they initiate their movement, their backs are basically parallel to the ground,” says Elliott. “Sometimes their heads are below their hips. That system never gets used in a game. It’s irrelevant. What matters is how fast you jump.” He pauses. “You can have two guys who jump 34 inches, and one has an amazing system for basketball, and the other, not so much. And everybody’s going to want to know that.”

For now the NBA is moving slowly. The assessments were kept confidential by P3 last year as part of a test program. It’s easy to imagine potential applications in the future, though. If you’re a player, wouldn’t you want to know how to avoid injury? If you’re a GM, wouldn’t you want to know who was at risk? Those are questions that will need to be addressed at some point. “The players who would not want to do it are thinking only about the draft moment,” says Korver. “They have something wrong with them and don’t want teams to know. I get that. A rookie contract can make you a bunch of money. But it’s not about making the NBA but lasting in the NBA. A 10-year career can make you a lot more money. And you’re going to have to deal with that bad knee in the first couple of years anyway.”

This type of data is clearly of great value to players and their agents, but it may be of even more value to teams. With a new collective bargaining agreement and a potential lockout on the horizon, the crucial question becomes, Who owns this kind of information? Says one GM, “The more data the better, but we’re on the cusp of employment law here.” Talk to legal experts, and they say the information, if valid, is close to being medical data, and P3 would need a written disclosure agreement to be able to talk about it. (Players would also have to give their consent for the data to be gathered.) Eddy Curry once clashed with the Bulls over his DNA records, invoking privacy law. This isn’t that different.

In the end, whether it’s P3 or the league or the teams doing the assessments, the outcome seems inevitable. The data has too much potential value to all involved. “Do you really want to stick your head in the sand?” says one GM.

“After all, it’s your body.”