NBA players making their voices heard as new civil rights movement rises

There are two boys from Baltimore. Both were raised on the city’s west side. Both grew up poor. Both are black.

One boy’s mother was addicted to heroin. She couldn’t read. When the boy was young, he developed harmful lead levels in his blood, a condition shared by many low-income Baltimoreans exposed to the toxic substance in housing structures before lead-based paint was regulated. Exposure to lead can cause a variety of medical and psychological problems. The boy fell behind in school. He racked up more than a dozen arrests and several convictions, mostly on drug charges.

The other boy’s father died of liver cancer when the boy was two years old. When he was eight, he and his family moved from Brooklyn to Baltimore, where the boy lived just blocks away from rampant drug dealing and violence in nearby housing projects. He played sports with his friends to stay out of trouble. The boy later said that drug dealers pushed him away from the streets. “I guess they saw something in me,” he said in 2006.

What they saw in the second boy was his remarkable basketball talent. His name, now familiar to fans all over the world, is Carmelo Anthony. He is a eight-time NBA All-Star and a global celebrity who signed a nine-figure extension with the Knicks last summer.

The first boy’s name is also famous, but for a much different reason. Freddie Gray was the 25-year-old man whose killing at the hands of Baltimore police last month sparked widespread protests and unrest in Baltimore and demonstrations around the country. Gray sustained a severe spinal cord injury in the back of a police van after being arrested under dubious circumstances, and he died of his injuries a week later. Gray’s death was the latest in a string of high-profile cases across the country in which police have killed unarmed black men, with names like Eric Garner, Mike Brown and Tamir Rice becoming rallying cries for a nationwide movement protesting injustice.

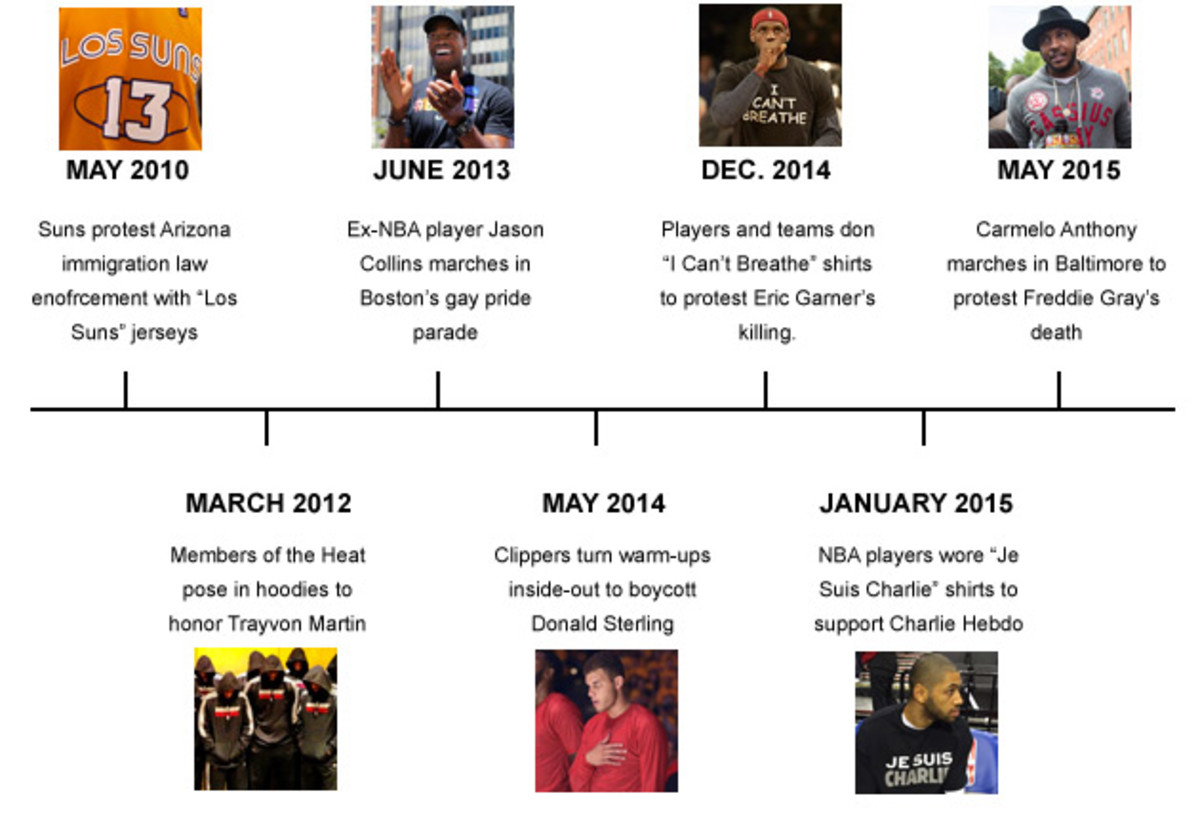

On April 30—11 days after Gray died and 18 days after he sustained fatal injuries while in police custody—Carmelo Anthony marched in Baltimore, joining thousands of citizens protesting Gray’s killing.

“This is my community. It’s not [only] my community, it’s everybody’s community,” Anthony told CNN while marching. “It’s America’s community.”

As he marched through the city he calls his hometown, Anthony wore a sweatshirt with the name “Cassius Clay” emblazoned on the front. Clay, who later changed his name to Muhammad Ali, is one of great revolutionary figures in sports history. The boxer became a hero to the counterculture movement with his anti-establishment actions and rhetoric.

While Anthony is certainly no Ali, the Knicks star’s presence in Baltimore added to a growing crescendo of NBA players making their voices heard on social issues. Despite the long-held belief that modern athletes are apolitical, over the last year the NBA has emerged as America’s most socially conscious professional sports league, with players speaking out on a scale unseen in decades.

The increased willingness of players to discuss social issues has been particularly acute over the last year, coinciding with a new era of civil rights activism across the country fueled largely by social media, increased access to recording technology, and high-profile police killings of black men. Players are increasingly engaging in political activism both because they feel closely connected to the 21st-century version of the civil rights movement and because social media has given them a larger platform to share their views.

“It may be that we’re hearing more from players because this has been an especially active couple of years in terms of…issues that not surprisingly would get their attention,” National Basketball Players Association president Michele Roberts says. “It’s actually refreshing to see the players not merely be engaged in their business—and that is basketball—but to express themselves as members of our community.”

Other professional sports leagues haven’t witnessed the same scale of protest. While a number of NFL players over the last year have used their platforms for political statements, like Cleveland Browns safety Jonathan Bademosi or several members of the St. Louis Rams, the league’s marquee players have largely remained silent, a stark contrast with the NBA. Other leagues also haven’t seen the group-oriented protests that have characterized NBA players’ embrace of political activism.

Last May, the Clippersprotested team owner Donald Sterling’s racist comments—in which he said he didn’t want black people coming to his games—by turning their warmups inside out and hiding the team’s name and logo. In the days that followed, Golden State was prepared to walk off the court and boycott a playoff game against Los Angeles and there were rumblings that LeBron James would lead a league-wide sit-out if Sterling were allowed to remain owner in power. This season, amid widespread public demonstrations against police brutality, NBA players have shown their solidarity once again, utilizing a variety of methods both on and off the court.

The growing chorus of NBA voices discussing social issues underscores the fact that despite their wealth and status, many players do not feel insulated from racial discrimination. The national conversation over the relationship between police and minorities is all too familiar for a number of players.

“I think when you look at the situations that are going on, a lot of us come from these same neighborhoods,” says Magic guard and 12-year NBA veteran Willie Green. “Whether it’s [Mike Brown in] Ferguson, whether it’s [Eric Garner in] New York, whether it’s Trayvon Martin in Florida, whether it’s [Freddie Gray] in Baltimore, we come from similar backgrounds. So this kind of hits home with us.”

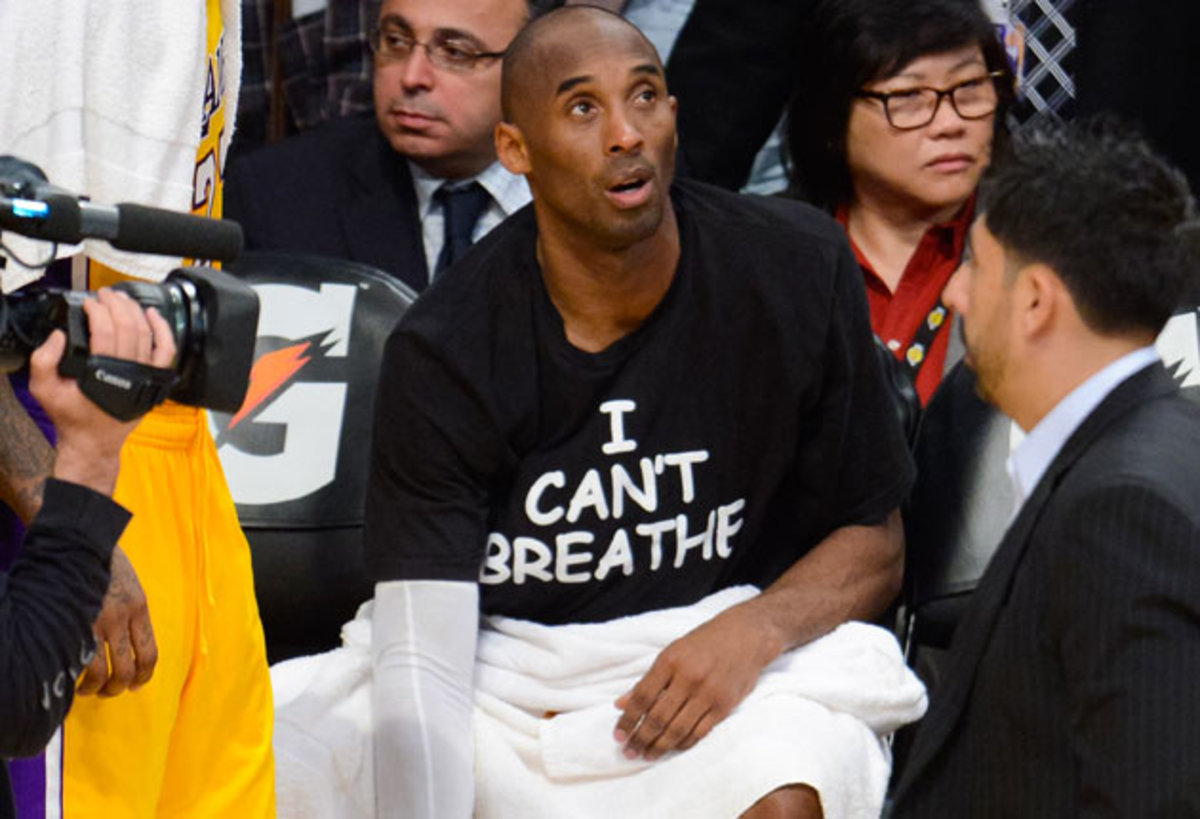

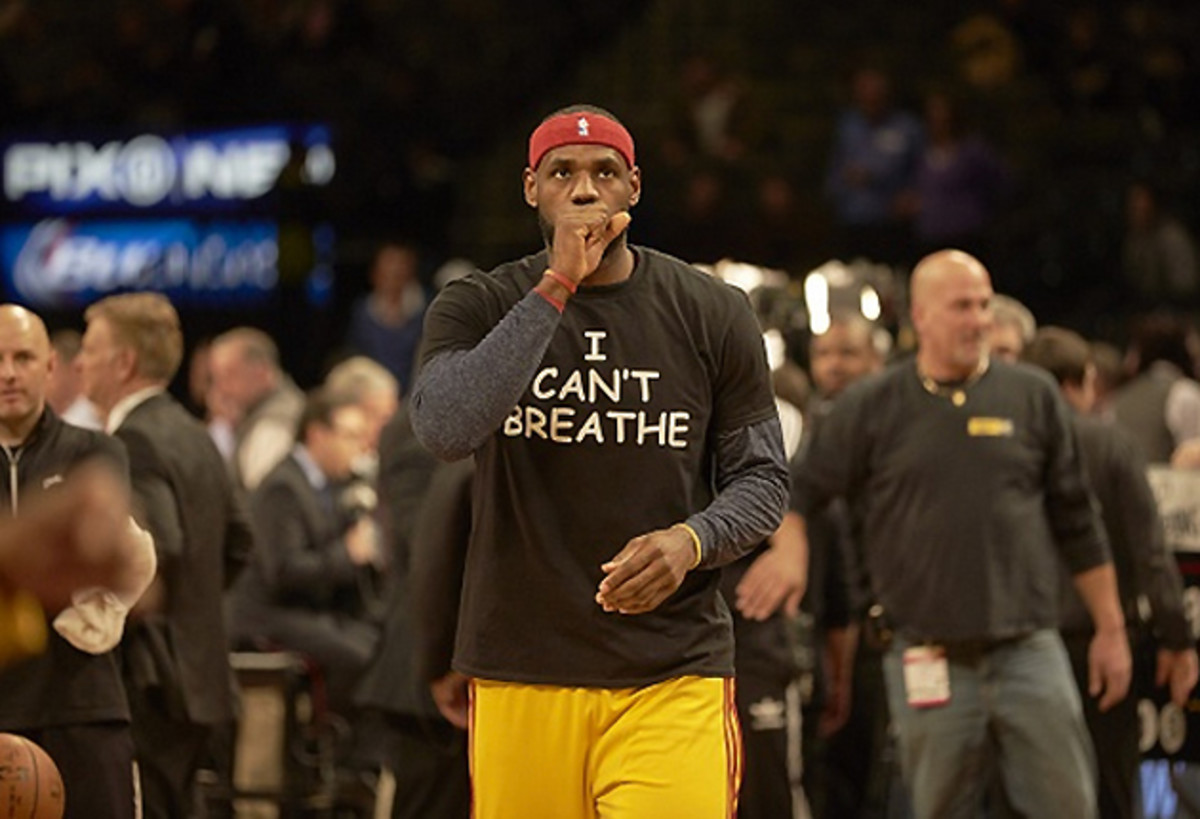

What makes the social consciousness of NBA players noteworthy is not just its widespread nature, but also that star players have not shied away from making political statements. In addition to Anthony, stars like LeBron James, Kobe Bryant and Derrick Rose have used their platforms to protest, with all three players notably donning “I Can’t Breathe” shirts before games in December after a Staten Island, N.Y., grand jury failed to indict the police officer who issued a fatal chokehold on an unarmed Eric Garner last July.

Star players haven’t always been so willing to openly discuss polarizing issues. In 1993, Charles Barkley—who hardly shies away from discussing his political agenda today—famously declared, “I am not a role model.” Michael Jordan also notorionously stayed away from political controversy. But in today’s NBA, stars are taking a leading role.

“It is interesting that the so-called marquee players have at least for the last two years been vocal in response to issues that move them. I think that’s great,” Roberts says. “These guys are role models, whether they like it or not. And people do pay attention to what they do, whether they like it or not. And so, if there is a statement that they want to make about a significant social issue, it is frankly a privilege that they have that they can make those statements and people will listen and maybe be persuaded.”

The “I Can’t Breathe” display was the most wide-ranging athlete protest in recent memory. Entire NBA teams joined some of the league’s marquee players in wearing the shirts, which brought Garner’s last words onto the hardwood and sparked backlash from some who felt athletes shouldn’t blend politics and sports.

NBA commissioner Adam Silver, while praising players for expressing themselves and taking a stand on social issues, has said that he prefers players abide by the NBA’s on-court dress code, begging the question of when a demonstration crosses the line.

“One of the reasons why I think that it is appropriate for me to draw that line in terms of political activism around our games is that I think our players have so many other opportunities and have a platform to express their points of view on a variety of issues,” Silver said in April. “So it doesn’t necessarily need to be within the four corners of our playing surface.”

The majority of player activism has been kept off the court. But if history serves as any guide, it’s impossible to separate what occurs on the court with politics. And with civil rights abuses increasingly in the headlines, NBA players—many of whom, like Anthony, feel a deep connection to communities most affected by these abuses—are likely to continue speaking out against perceived injustices.

The tale of the tapes

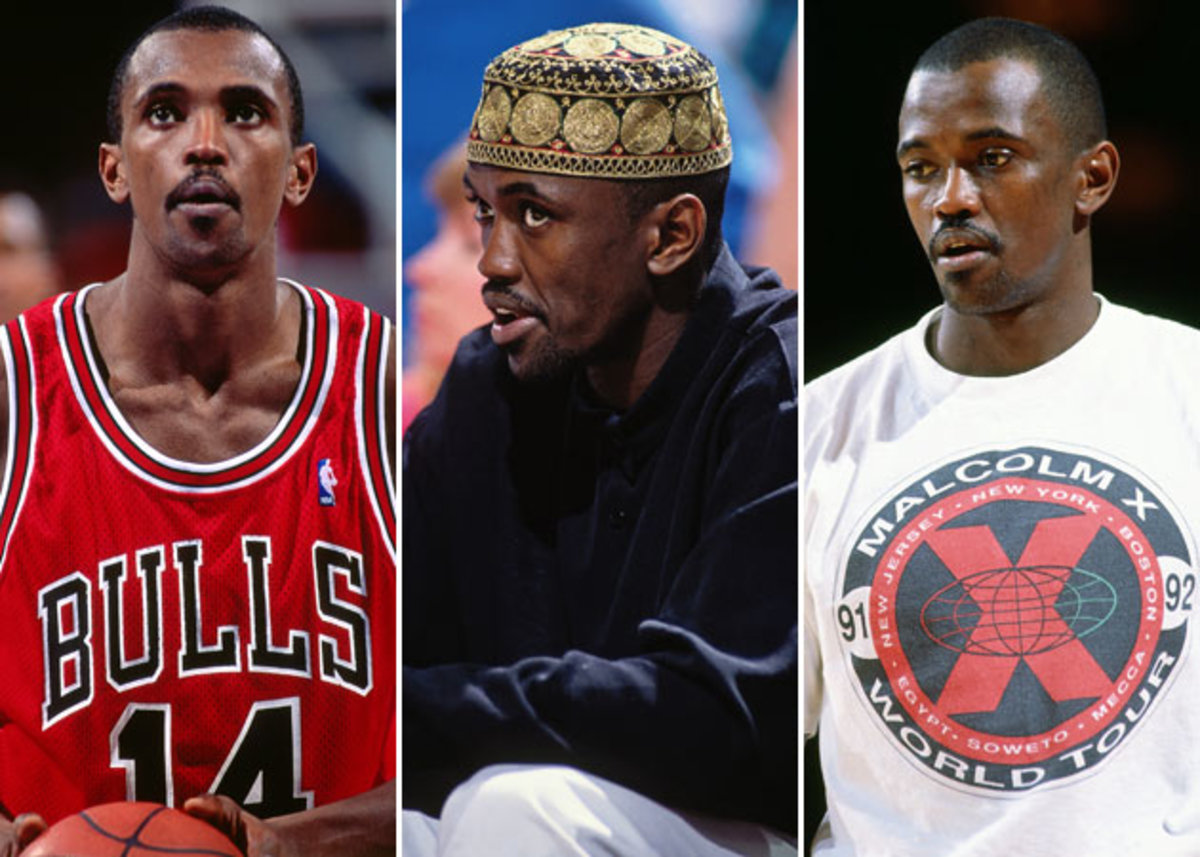

Though the NBA has recently witnessed a significant uptick in player activism, numerous players over the years have loudly defied the stereotype of the apolitical athlete. In 1992, Bulls three-point specialist Craig Hodges wore a dashiki to the team’s White House visit following Chicago’s NBA Finals victory. He also delivered a letter urging President George H.W. Bush to help poverty-stricken black communities. Hodges, only 32 at the time, never played another minute in the NBA, which he attributes to his actions at the White House even though he played less than 10 minutes per game in his final season.

“At 32 years of age, man, I was at peak performance as far as my jumper and as far as my legs were concerned. I could have played another at least seven or eight years, just hooping,” says Hodges, who was also known for his attempts to encourage Jordan to draw more attention to social and political issues. “But the ramifications of speaking up for your people can be devastating to your family.”

More recently, Steve Nash loudly opposed the Iraq War in 2003, when it was largely unpopular to do so. Nash, then with the Mavericks, wore a shirt during pregame warmups that read “No War. Shoot For Peace,” later telling reporters that he felt the war would be a “mistake” and that it had “much more to do with oil or some sort of distraction.” Nash’s comments predictably led to backlash, including a message to “shut up and play” from Skip Bayless, then with the San Jose Mercury News.

Nash also helped lead the franchise’s “Los Suns” movement in 2010, to show support for the Hispanic community against Arizona’s highly controversial SB 1070 immigration enforcement law, which critics said encouraged racial profiling. Phoenix wore the "Los Suns" jerseys for a playoff game against the Spurs, with Suns managing partner Robert Sarver saying “our basic principles of equal rights and protection under the law are being called into question.” (In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the part of the law mandating that police arrest and detain individuals suspected of committing a crime and for whom there is “reasonable suspicion” the person is in the country illegally, though three other aspects of the law were deemed unconstitutional.)

Another player who spoke out against the Iraq War was Etan Thomas, whose forceful anti-war speech at a rally in 2005 made him a hero to many on the left. Thomas, who played seven of his nine NBA seasons with the Washington Wizards and last played in 2011 with the Hawks, developed a reputation as the NBA player most closely associated with political activism in recent years.

Thomas rejects the idea that players were politically indifferent in the past, saying that athletes are more emboldened to speak out publicly nowadays in part because new recording technologies have allowed civil rights abuses to be seen by more of the public.

“It’s not like these things haven’t been happening for decades, but now you’re just seeing it more. And I think that’s why…just overall in society people are reacting to police brutality and reacting more to this stuff now,” Thomas says. “Not just athletes, just in general, because you’re being shown more. You’re actually seeing it on video. That’s a big difference.”

Seeing or hearing an injustice on tape has been a powerful instigator of protest, particularly over the last year. Police killings caught on video, such as Garner’s death, have sparked national outcry that might not have existed without a recording. In the NFL, TMZ’s publication of a tape showing Ravens running back Ray Rice knocking out his then-fiancée in a casino elevator galvanized criticism of Roger Goodell’s two-game suspension of Rice and forced the commissioner to institute a longer ban. The league also adopted a new domestic violence policy. In the NBA, the Donald Sterling saga last year showed that a tape can have a similar mobilizing effect on the league’s players.

The former Clippers owner’s racist remarks were not a surprise to those familiar with his history. Sterling was the target of two major housing discrimination lawsuits, including one by the U.S. Department of Justice in 2006. In that lawsuit, Sterling was accused of refusing to rent apartments in California to black people. In a previous 2003 housing discrimination suit, Sterling was sued by 19 plaintiffs who alleged that he attempted to push black and Latino tenants out of buildings he owned. That lawsuit, filed in federal court, accused him of saying that “black tenants smell and attract vermin” and that “Hispanics smoke, drink and just hang around the building,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

But there was no recording. There was no media uproar. There were no league-wide protests. There was no lifetime ban, at least not until the infamous tape surfaced. A recording shoves bigotry in your face and makes it impossible to ignore.

“That’s the power of the tape,” Thomas says.

Just as easier access to recording devices has helped raise awareness on racism and civil rights abuses, new communication technology has also given NBA players a larger platform to make their voices heard on social issues. In many ways, the activism we’ve seen from players in recent years—from protests against Donald Sterling to “I Can’t Breathe” and more—has been crafted by the age of Instagram.

University of Southern California professor Todd Boyd, who studies race, media and sports and wrote Young, Black, Rich and Famous (2008) about hip-hop and the NBA, points to the Miami Heat’s 2012 Trayvon Martin photo tribute, in which the team wore hoodies to protest the 17-year-old’s killing, as a watershed moment for this new form of activism.

“In the age of social media, we’ve seen these political [statements] in ways we haven’t seen for a long time,” Boyd says.

Besides giving athletes a direct line to fans, social media gives players the ability to voice their thoughts on any subject at any time. This unfettered soapbox access is a luxury that athletes didn’t have before a few years ago. Endless mainstream media coverage only intensifies the ripples a high-profile figure can create on social media: LeBron James and Kevin Durant can take over a news cycle with a tweet.

The Heat’s Trayvon Martin tribute was an act of solidarity that would have been hard to imagine occurring before social media. LeBron James posted the photo online with a powerful message: #WeAreTrayvonMartin.

#WeAreTrayvonMartin #Hoodies #Stereotyped #WeWantJustice http://t.co/tH6baAVo

— LeBron James (@KingJames) March 23, 2012

An Instagram photo with a few hashtags might seem to pale in comparison to the great athlete protests of the past, when figures like Ali put their careers on the line to make political statements. Still, how much of a difference athletes make when they speak up on big social issues like civil rights is difficult to gauge.

“I think sports historians tend to overplay, and then other historians either allay or marginalize or neglect the role of the athlete in social change,” New York University professor of history Jeffrey Sammons says. Even Jackie Robinson breaking Major League Baseball’s color barrier effectively enriched a white institution while destroying a black institution, the Negro Leagues.

But while the modern athlete’s role in creating social change is small, speaking out on social issues raises awareness among groups that might not otherwise be paying attention to injustice. The simple act of wearing a t-shirt or sending a message online can be meaningful, says Dr. Harry Edwards, who organized the 1968 Olympic Project for Human Rights and wrote The Revolt of the Black Athlete.

“Every generation of athletes expresses themselves politically within the context of their own times,” says Edwards, who is a professor emeritus of sociology at University of California-Berkeley. “You cannot expect LeBron and D-Wade and the five players from the Rams [who put their hands up to protest Ferguson, Mo., teenager Mike Brown’s killing] and so forth to express themselves the way that athletes did in the 1960’s anymore than you could have expected the athletes in the 1960’s to express themselves in the way that Jackie Robinson did or that Joe Louis did or that Jesse Owens did.”

Insulated from discrimination? Think again

Despite leading the Celtics to 11 championships in 13 seasons with the team, Bill Russell didn’t always feel loved by Boston. During his time in the city, he experienced blatant bigotry, including his home being vandalized with racial epithets during a break-in. Russell, like so many other athletes who predated and intersected the Civil Rights movement, faced unabashed discrimination and prejudice.

The more transparent social injustice of yesteryear led to some of the most celebrated athlete protests in history, like Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ black power salute at the 1968 Olympics or Muhammad Ali’s resistance to the Vietnam War draft. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, then Lew Alcindor, boycotted the 1968 Olympics. In 1965, black players and some white players boycotted the AFL All-Star Game in New Orleans after experiencing firsthand discrimination in the city.

The reality is that athletes today don’t experience nearly the same amount of discrimination, says NYU professor of education and history Jonathan Zimmerman. But that doesn’t mean structural racism and civil rights abuses don’t exist. They’re just more difficult to see.

“Why can’t we say there’s been enormous progressive change since 1965 and not nearly enough of it? This doesn’t seem to be inconsistent at all,” says Zimmerman, who wrote about the NBA's "I Can't Breathe" protests for The New Republic in December. “It’s only in these unbelievably polarized moments that either we have to say there’s no racism or nothing has changed. Neither of those statements are historically defensible.”

NBA players have made clear that they feel compelled to speak out on social issues because they feel personally connected to communities or individuals who experience injustice. And despite conventional wisdom that athletes are coddled and live in a different universe from the general public, players also say they aren’t immune from discrimination.

In many ways, it shouldn’t be surprising that NBA players have shown the greatest willingness to discuss social issues: The league was 76.3% African American in 2013, so naturally players feel the urge to speak up about racism, which has been a major focus of national media coverage over the past year amid considerable demonstrations against police brutality, particularly in Ferguson, New York and Baltimore. Most players aren’t demonstrating against U.S. foreign policy or economic inequality, two concerns that were also recurring subjects of athlete protests in the 1960’s. Players are largely focusing their political statements on police brutality and racism due to what Edwards calls a “sense of shared vulnerability.”

Dwyane Wade, who appeared with his sons wearing hoodies to support Trayvon Martin on the cover of Ebony in 2013, said he felt obligated to speak up about the case because of his own sons. Nets guard Jarrett Jack said at the time of the “I Can’t Breathe” t-shirt protest that he and other players protested because they were concerned about their safety. Cavaliers guard Kyrie Irvingsaid that the Eric Garner case “hits close to home."

Just because players are speaking up en masse doesn’t mean their opinions are uniform. While some players choose to focus on the racial component of civil rights abuses, others prefer to refer more broadly to “justice,” as Kobe Bryant did after wearing an “I Can’t Breathe” shirt in December. In 2014, Bryant also discussed the Heat’s Trayvon Martin photo, telling The New Yorker that he didn’t want to automatically defend Martin because “if we’ve progressed as a society, then you don’t jump to somebody’s defense just because they’re African American.”

But over the past year, national news coverage of racial injustice specifically has struck a chord among many NBA players. Despite the presumption that athletes feel protected by wealth and status, Detroit Pistons veteran forward Anthony Tolliver says he and other players still feel the effects of discrimination.

“When you’re good at sports, you get a certain amount of insulation from your environment,” Tolliver says. “But the thing is you’re not always in those environments. When you’re outside of those environments where people know who you are and what you do, you’re just another black guy.”

Says Green: “I’ve walked to the store plenty of times with a hoodie on. And it had nothing to do with the fact that I was trying to be gangster or whatever…it was chilly outside, I put a little hoodie on and I walked to the store. So now being older I can definitely feel the pain that some parents are going through and just some communities are going through.”

Thomas is particularly blunt: “Once you step off the court, you’re like any other black man, where you’ll be stopped by the police, you will be looked at as a suspect, you’ll be looked at as a criminal.”

Police violence and the NBA intersect

A recent incident between Atlanta Hawks forward ThaboSefolosha and the New York Police Department is timely evidence that NBA players are not strangers to discrimination.

On the morning of April 8, Indiana Pacers forward Chris Copeland was stabbed outside a New York City nightclub. Police later said that while they tried to set up a crime scene, Sefolosha and teammate Pero Antic obstructed them, leading to both players being arrested.

During the arrest, Sefolosha broke his right fibula and suffered ligament damage. He was charged with resisting arrest, disorderly conduct and obstructing governmental administration. The NYPD arrest report said Sefolosha resisted arrest and charged an officer, forcing several officers to intervene to subdue the 6’7’’, 222-pound Swiss forward.

But the NYPD’s account of the night differs sharply from Sefolosha’s. The Hawks forward released a statement a week after the incident that placed blame for his injury squarely on police.

“I will simply say that I am in great pain, have experienced a significant injury and that the injury was caused by the police," he said.

Two videos of the incident published by TMZ showed several officers surrounding Sefolosha and attempting to grab him. The officers eventually bring Sefolosha to the ground, at which point one officer swung his baton with a subdued Sefolosha. It’s unclear in the video whether the baton makes contact with Sefolosha.

“The video speaks for itself,” the forward told reporters on April 15. Sefolosha’s injury will sideline him until next season.

The NBA and NBPA are still investigating the incident, and ESPN reported last month that Hawks officials were questioning why police held Sefolosha for several hours despite having a broken fibula.

Roberts says Sefolosha has a reputation for being a “gentle giant,” and she also said that she believes his assertion that he did not provoke the officers. She says that while she still wants the circumstances to become clearer before making a final judgment, the incident demonstrates that professional athletes are not necessarily immune to aggression from law enforcement.

“We were all very, very concerned about what happened to him. And frankly it does underscore that if it can happen to someone of some celebrity, it’s something that can happen to the average guy,” Roberts says. “Our players are not poor, so [they] don’t live in economically challenged communities, where the evidence seems to suggest these kinds of things happen more frequently. That having been said, a man of color, which Thabo is, apparently can find himself in some jeopardy.”

Sefolosha’s interaction with the NYPD demonstrates why many NBA players don’t feel like their status completely insulates them. Tolliver called the incident “disturbing,” saying that NBA players feel protective of each other.

“This is a brotherhood. We kind of look at the NBA as a kind of fraternity. And so when you hurt one of our brothers, you hurt us,” Tolliver says. “It definitely means more and hits home more whenever you’re talking about a fellow brother that gets hurt and that gets abused from police brutality, allegedly.”

Boyd says the Sefolosha incident could have a galvanizing effect.

“If players start to feel like they are potentially going to be attacked by police and they use Sefolosha as an example, then this is sort of thing that raises consciousness,” Boyd explains.

As long as civil rights abuses remain topical—and there’s no sign that these problems are going away anytime soon—NBA players are likely to continue using their platforms to discuss social issues, particularly if more players are personally affected like Sefolosha. Even though wearing a t-shirt, sending a tweet or even marching with protesters may seem like tiny actions in the face of massive problems, these small acts of protest all raise awareness among sports fans about political issues, which affect athletes no matter how many times detractors urge ballplayers to “stick to sports” or “keep politics off the field.”

Thomas, who has experienced the backlash of discussing politics as an athlete firsthand, says NBA players who choose to speak out should be praised for talking about controversial issues.

“You have to be wiling to accept that you’re going to get criticized when you speak up for something,” Thomas says. “So I think somebody like Carmelo needs to be praised for what he is doing. Because it takes a lot of courage.”

Despite similar starting points, the lives of Carmelo Anthony and Freddie Gray took drastically different paths. Gray’s life was cut short and confined to the streets of West Baltimore, while Anthony attained global fame as one of the best basketball players on the planet. Gray became a symbol of injustice. Anthony became an emblem of success. But the road Anthony took to stardom comes from West Baltimore, and it’s a two-way street back home.