SI Vault: The extremely high bar set for NBA manchild Darryl Dawkins

Editor's note: Darryl Dawkins, a former star with the Sixers and Nets, died on Aug. 27, 2015, at the age of 58. In honor of the legacy he leaves behind, SI Vault takes a look back at his career, starting with his entry into the NBA as an 19-year-old manchild. This story originally ran in SPORTS ILLUSTRATED on April 11, 1988. To subscribe, click here.

Close your eyes. Imagine you are 18 years old again and back in high school. But now you are 6'10" and weigh 240 pounds. Everyone in school knows your name. No one insults you when you walk through the halls. You are a terrific athlete. You have muscles layered on muscles, sculpted on a body that can move with the speed and reactions of players who are a foot shorter. And you can play basketball. Really play. You have the height and power for the inside game, and you also have 20-foot jumpers and no-look passes and behind-the-back dribbles down pat. You can rebound and you can block shots so hard and so far they look as if they were fired from a cannon. A basketball is half hidden by your monstrous hands. Your team wins the state championship because of you. The colleges are all kicking down your mother's front door to get you to sign with them and come to their campuses and chase coeds, pledge fraternities and decipher the complexities of English 101. Your house is mobbed with recruiters who smile all the time, displaying ear-to-ear teeth. But over in the corner is a small man in a dark trench coat who crooks his finger and beckons you. He opens a suitcase. It is filled with a million dollars.

"It's yours, "he says with a smile.

"What college are you from?" you ask him, unable to take your eyes away from the money.

He pauses before lie answers: "The college of hard knocks, Baby. The pros. And we want you. YOU got potential!"

Suddenly the alarm clock goes off and you wake up and realize you haven't grown an inch since the night before. Judging from how long it takes you to get from the bed to the bathroom, your reactions haven't improved, either. You realize it was only a dream.

• MORE NBA: Sixers, Nets legend Dawkins dies | Players remember Dawkins

Darryl Dawkins, who bypassed college and strode into the NBA directly from high school, had the same dream—but he never woke up. His dream merged into reality with such swiftness that at times it was hard for him to tell the two apart. Was he an 18-year-old high school kid playing in the pros, or was he a pro with the adolescent cares of a high school kid?

"Darryl has always thought life was a big lark." says Pat Williams, the Philadelphia 76ers former general manager. "He never realized how serious this business is to most of us who make a living at it."

"What is your church preference, Darryl?"

"Redbrick, "Sir Slam replied.

It seems hard to believe that he has played 13 seasons in the NBA. Wasn't it only yesterday that he was plucked out of Maynard Evans High School in Orlando, Fla., taken as a hardship case in the first round of the 1975 draft by the 76ers and given a seven-year contract worth one million dollars? Don Nelson, the former Milwaukee Bucks coach, thought at the time. "In a few years we [are] all going to be treated to seeing one of the greatest centers in the game."

Instead, Dawkins's career is foundering. To most NBA coaches and fans and to the media, Dawkins is one of the greatest disappointments of all time.

But why?

Dawkins averaged almost 13 points a game through 712 regular-season games and more than 100 playoff games. He has played in the NBA championship finals three times and in the conference playoff finals three other times. Only once has a team he was on not made the playoffs: in 1986-87, with New Jersey, when he missed all but six regular-season games because of a back injury, which required surgery. He has played with some of the best in the league during the last decade: Julius Erving, Maurice Cheeks, Buck Williams, Bobby Jones, Doug Collins. And he is the third-leading field goal percentage shooter in NBA history.

Even though he has achieved some dubious records as well, including most fouls committed in a season (386), his is still a career that should satisfy many players and critics. Dawkins himself seems pleased with his accomplishments. "I've had some good days and some bad days, but overall I'm happy with it," he says. Others aren't. For there were times he so completely dominated games that people wondered why he couldn't do it every night.

One word, potential, has manacled Dawkins as securely as any ball and chain. When it finally died, of frustration, on the lips of one coach, it was quickly taken up by the next—and the next and the next.

Ask Dawkins about that word, and he shakes his head. "It made me mad. Damn mad, really," he says. "Because everyone wanted to compare me to Chamberlain. I ain't got nothing to do with him. I'm just Darryl Dawkins, and that was never good enough."

"What is your favorite color, Darryl?"

"Plaid, "Chocolate Thunder replied.

Perhaps nothing in his career defines Darryl Dawkins better than the time he destroyed a backboard in Kansas City. It happened on the night of Nov. 13, 1979. There were 9,180 in the Municipal Auditorium to see the 76ers play the Kings. When it happened, 38 seconds into the third period, it was so terrifying in its ferocity and so unexpected that anyone in the audience who blinked at that precise moment missed it.

Dawkins, swooping in from the right side, had risen far above the rim, and the ball looked tiny and helpless in his huge hands as he readied to slam it. He had done this a thousand times before and had delighted the fans by gracing each of his dunks with imaginative names. There were the Rim Wrecker, the Go-Rilla, the Look Out Below, the In-Your-Face Disgrace, the Cover Your Head and the frightening Spine Chiller Supreme. But this one was different.

From his toes to the top of his head, 82 inches away, Dawkins said he was overcome by a force he later called Chocolate Thunder. He claimed he could not control its desire to "escape out of my body."

A moment later the backboard exploded with a crackling pop that sprayed thousands of shards of glass onto the floor. Players in the vicinity of the basket were momentarily stunned, then scrambled to get out of the way. There was a second or two of hushed disbelief, and then the arena broke into pandemonium.

NBA players remember Darryl Dawkins

It took one hour and eight minutes to replace the basket. For not only had Dawkins shattered the glass board, he also had bent the basket support pole with the force of his dunk. As both teams temporarily left the floor, the crowd began to mill around the court, picking up pieces of glass as souvenirs. Then Larry Staverman, the Kings' vice-president of operations, suggested the team should sweep up the pieces and sell them.

Of course, Dawkins had to name the Kansas City dunk, but this one required something special. He kept the world in the dark for a week before finally immortalizing Kansas City's Bill Robinzine (who had the misfortune of being under the backboard as it disintegrated) by calling it the Chocolate-Thunder-Flying, Robinzine-Crying, Teeth-Shaking, Glass-Breaking, Rump-Roasting, Bun-Toasting, Wham-Bam, Glass-Breaker-I-Am Jam. That seemed to say it all.

But, as always, the sensational dunk didn't mean much. His team lost, and everyone wanted to know why a guy that big and that strong and that fast, one who could break backboards in a single bound, couldn't manage to get more than six rebounds a night.

"When did you start naming dunks, Darryl?"

"It started against Buffalo. I threw one down against this guy. BOOM! He ducked and looked back at me and said, shocked, 'What was that?' I thought about it for a second and I said, 'Yo-Mama!' "

The speculation on his potential began early for Dawkins and reached a crescendo in his last year of high school. As a senior at Maynard Evans, where he averaged 20 points and 11 rebounds a game, Dawkins had already grown to 6'10", his height while in the NBA. Jack McMahon, who was then an assistant coach and scout for the 76ers, remembers the first time that he saw Dawkins play. "Pat Williams had gotten a tip from an old friend of his, former major league pitcher Jim Kaat, that there was a high school player we should come down and look at," McMahon says.

So McMahon was dispatched to Florida with orders to phone Kaat on his arrival, and Kaat would make arrangements for McMahon to attend the game. McMahon arrived in Orlando, called Kaat and got a housekeeper who spoke only Spanish. Unable to contact Kaat, he was momentarily at a loss. "I didn't even know Dawkins's name or where he played, because Kaat was supposed to be arranging all of this," he says. McMahon finally called a local paper and asked where he could see the best big man in the city play that night. He got to the gym early and watched the JV game. Then the small gym began to fill rapidly. "I started talking to people around me about Darryl and everyone loves him and then they come out of the locker room," McMahon says, chuckling as he recounts the story. "Out come a few little guys. Like normal high school kids. Then out comes Darryl. He had his head shaved back then. But, hey, no way can this kid be in high school! He's got to be 25 years old. Same body as he has now. Got 44 points with four guys sagging back on him every time."

McMahon was impressed enough to give Williams an ecstatic report, and then they waited for Sixers coach Gene Shue to get a chance to scout Dawkins. Both were concerned because, says Williams, "Gene was usually not overly impressed with young players."

Shue finally saw Dawkins in the state tournament in Jacksonville. That night, Williams, who was at the Atlantic Coast Conference Tournament in North Carolina, remembered being so anxious to hear Shue's reaction that he pulled off the road and called the coach's motel room from a pay phone. Shue, as the others before him, couldn't believe the size of Dawkins. "He was a giant playing with little kids. He did unbelievable things on the court for someone that size," Shue recalls. However, Shue noticed something else, an omen of things to come. "Even then he was inconsistent. He did the good things only every so often," he says.

Williams had thought about scouting a high school player after the Utah Stars of the American Basketball Association drafted Moses Malone out of Petersburg. Va., in 1974. "I wondered if there was another Moses out there." Williams says. So he put together a list of high school players who had the potential to be in the NBA.

There were but three names: Bill Cartwright, Bill Willoughby and Dawkins. After seeing each of those players, and also weighing the merits of Marvin Webster, Joe Meriweather and Rich Kelley, the top senior centers coming out that year, the Sixers staff decided that Dawkins was worth the gamble.

When he heard the news, Al Domenico, the 76ers trainer, thought, "Are we nuts? What can you possibly do with a kid coming out of high school?" Steve Mix, one of the team's veterans, remembers wondering "why we wasted a good draft pick."

Others had few doubts. McMahon, one of the league's most astute judges of talent, thought Dawkins "was probably still going to grow. He could possibly get to seven foot three in a few years. No other center at that time had that potential."

"When is your birthday, Darryl?"

"January 11th."

"What year?"

"Every year," Chocolate Thunder retorted.

Being 18 is a time for many things in a young man's life. It is a time to rejoice in that feeling of invincibility that youth brings. There are cars, girls, parties, hanging out with the guys, sports. And in the privacy of his room an 18-year-old stares at the posters of his favorite professional stars, and dreams. But what do you do when the next time you walk out your door the dream is reality?

"Everyone always thinks because you are big for your age that you can handle things better or you are more mature when in reality nothing is further from the truth," says Bob Lanier, the former Milwaukee Bucks center. Julius Erving puts it even more simply: "When they see a seven-footer, everyone thinks—the Franchise. How many players could handle that at 18?"

It was at this point in his young life that Dawkins made a decision that will be debated whenever his name comes up. He chose not to go to college. The chance to help his family made the Sixers' offer one he couldn't refuse.

He had originally planned to attend college, and had narrowed his choices to Florida State and Kentucky. But financial considerations left him little choice. As he says today, the decision was a relatively easy one: "I knew when I saw my grandmother working two jobs just to barely make ends meet, and she gave me her last 10 dollars just so I could buy some sneakers, that I had to do it."

Though his mother and father were separated at the time, they both left the decision to him. "My mother always told me that I should learn to make my own decisions," says Dawkins, "because then if they didn't work out I would have to live with them."

A sense of family burns strongly in Dawkins. He grew up the second-oldest child in a family of four brothers and two sisters. And though he describes his childhood as "poor but happy," the fact that the Dawkins children sometimes had to live with relatives because money was scarce left an indelible impression on him.

Dawkins was raised by his late grandmother, Amanda Celestine Jones, and she had a profound influence on his early life. By the time Darryl was nine, she had taught him to clean, cook, iron and sew. "She said I might never get married so I'd better learn to do these things for myself," he says. In addition, there were always odd jobs to do. "If you didn't work, you didn't eat," he says. So Darryl and his brothers picked fruit, raised chickens, chopped wood and painted houses. His brothers and sisters were his best friends, and he rarely developed close friendships with other kids. "Our nearest neighbor was probably a mile away," Dawkins recalls. He didn't change when he joined the 76ers. He didn't develop many close friendships outside his family and a few trusted advisers—such as Rev. William Judge—who had counseled him during his high school days. He had many acquaintances but few saw beyond the laughing, wisecracking mask he wore most of the time. When a conversation or interview struck a raw nerve, he reacted like a comedian—deflecting questions, going into his Chocolate Thunder/Lovetron patter—to lead the talk to safer ground.

NBA players remember Darryl Dawkins

The feeling is almost unanimous among those who have coached or played with Dawkins that college would have been an enormous stimulant to his early development.

Billy Cunningham, who coached Dawkins for five years in Philadelphia, believes "the extra time you can spend with a player [in college] and the daily structure would have been beneficial."

Similar sentiments are echoed by many of Dawkins's former teammates. Erving, who completed only three years at the University of Massachusetts before joining the ABA in 1971, says Darryl would have benefited from "just the repetitive drills you do in college. If you do something a thousand times more, it instinctively becomes part of your game. What he also missed was just the fun you have during those college years. It's a great time for self-discovery and laughter without a lot of pressure on you to be great. A lot of the time that coaches thought Darryl should be working harder on basketball he was out having fun like any other 18-or 19-year-old kid. Life was still just fun to him; it wasn't a business."

There are dissenters who claim that college wouldn't have helped Dawkins all that much. McMahon says, "Darryl was meant to be a ballplayer. The problem was not the lack of college, but that the group of players he broke in with could lend him no direction."

There were times when the fast track of pro ball threatened to derail Dawkins. He was young, single and had money to spend and a willingness to enjoy the pleasures that await any new sports celebrity in town, especially one with his size and penchant for the flamboyant. There were women and cars and parties and an ever-increasing number of glib quotes.

When he showed little improvement in his basketball skills, his off-court diversions became a source of irritation to 76er management. "The more the coaches could see how little he was using his skills, the more they felt they could teach him," Erving says.

"If he had one thing that held him back from greatness, it was that he was easily bored. He had a very short attention span," says Doug Collins, now the coach of the Chicago Bulls.

Dawkins, surprisingly, agrees with Collins. "If I learned how to do a move, why did I have to spend another hour doing it 500 more times?" he says. "I already showed you I could do it." Dawkins complained that former Nets coach Larry Brown kept him after practice 20 minutes every day for extra work. Did it help? "I'll admit it helped a little," Dawkins says. "But I could do most of that stuff in five minutes. Why did I have to stay for 20?"

His limited attention span was never more evident than during a practice, recalled by Cunningham, that Dawkins cruised through without breaking a sweat. "Darryl wasn't pushing himself, so I stopped practice," Cunningham says. "I went over to him and really read him the riot act. Really yelled at him. He had his head down and promised me he would do better." An incredulous smile forms on Cunningham's face as he finishes the story. "And then as I walked away—he tripped me! I couldn't believe it. What can you do? I finally cracked up laughing like everyone else."

Shue, his first coach in the pros and one whom Dawkins claims to like, says, "Darryl was always just a fun-loving giant. He enjoyed the good times more than the job. He should have been a better player, but he could never motivate himself to work at it."

McMahon agrees: "He loved the money, the action, the limelight; loved the whole scene. He just never loved basketball."

Dawkins disputes that. "I used to take losing hard in the beginning. I'd be really upset," he says. "The veterans would tell me that it would drive you crazy if you let every loss bother you. There was always a game the next night to get even. So after that I didn't let each loss bother me as much.

"Coaches only thought you worked hard if you had your tongue hanging out and were grunting and grimacing. But I go around with a smile on my face, and everyone thinks I'm not working hard."

The Philadelphia team that Dawkins played on his first year in the NBA hardly supplied the tranquil, stable atmosphere that a player directly out of high school needed. Back then, the 76ers were often described as a Wild West show. The players were talented, individualistic, spectacular, controversial and flamboyant. They swaggered into arenas and dared people to beat them. Cunningham, who was in the last year of his playing career, says one of the problems was that "everyone wanted to be a star." There were stars galore throughout the lineup: established stars like George McGinnis and, the next season, Julius Erving; rising stars like Collins and Mix; and, of course, the impatient young trio of rookies, Joe Bryant, Lloyd—now World B.—Free and Dawkins. Says Cunningham, "Everyone was concerned with projecting a certain image; fighting for recognition on a very talented team."

Dawkins remembers how impressionable he was that first year: "I'd come into the locker room at halftime and one guy would be smoking a cigarette and another would be drinking a beer. I just did the same thing."

The team was a great draw on the road, fueled as much by the controversial statements that appeared in the press as by the display of talent on the floor. No one was readier with a quote, a quip, an impersonation or an observation on life than Dawkins. Neil Funk, the team's broadcaster at the time, says, "Darryl got lost in the shuffle early with that team. He wasn't playing much at first, and he tried to get attention with his personality. He tried more than anyone to say the most outrageous or controversial thing."

GALLERY: Sports Illustrated's best photos of Darryl Dawkins

SI's Best Photos of Darryl Dawkins

Darryl Dawkins

January 16, 1980

Darryl Dawkins

January 17, 1980

Darryl Dawkins

January 19, 1980

Darryl Dawkins

1980 Eastern Conference Finals

Darryl Dawkins and Julius Erving

1980 Eastern Conference Finals

Darryl Dawkins and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

1980 NBA Finals

Darryl Dawkins and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

1980 NBA Finals

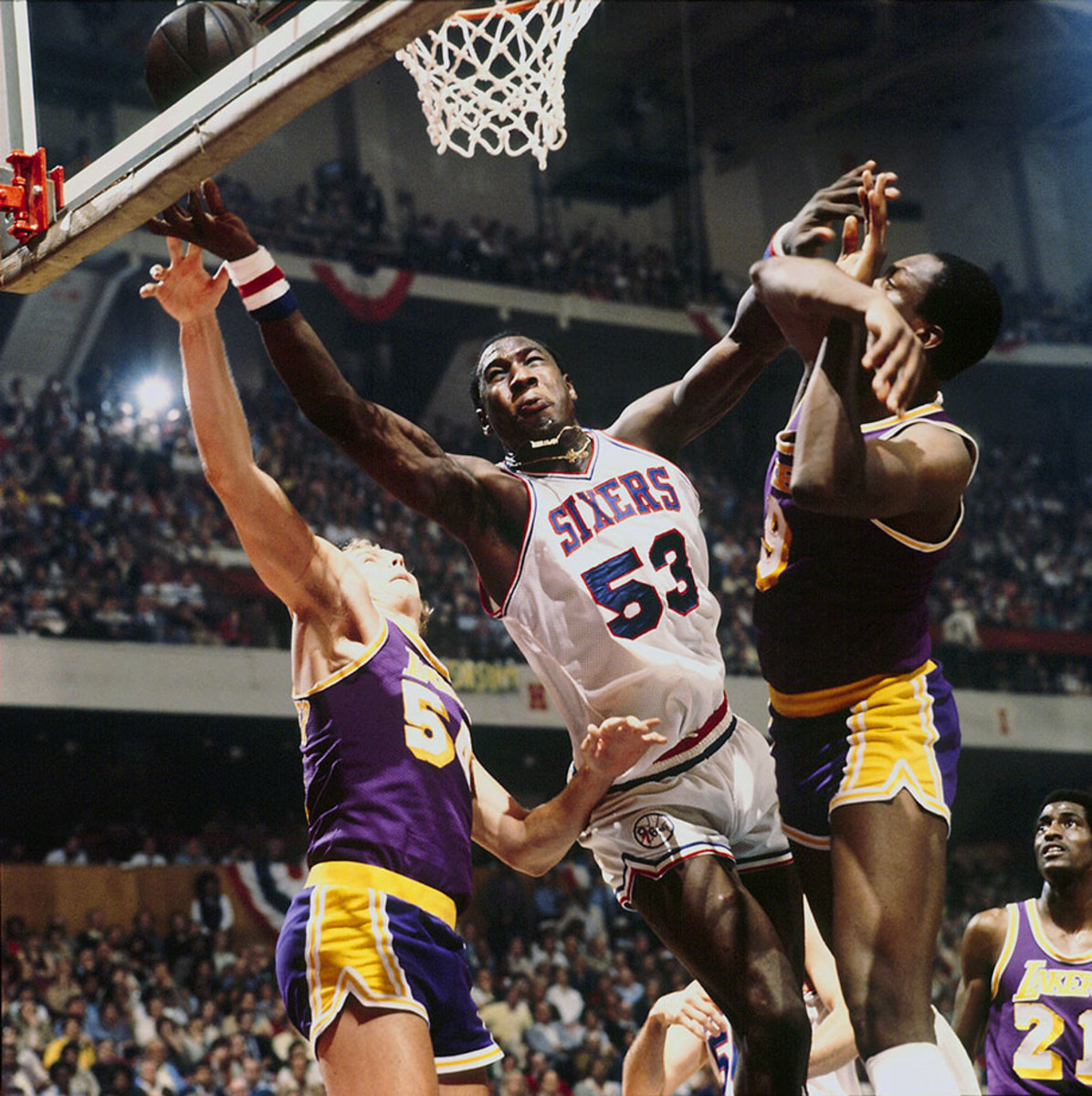

Darryl Dawkins, Mark Landsberger and Jim Chones

1980 NBA Finals

Darryl Dawkins and Mark Landsberger

1980 NBA Finals

Darryl Dawkins and Caldwell Jones

1981 Eastern Conference Semifinals

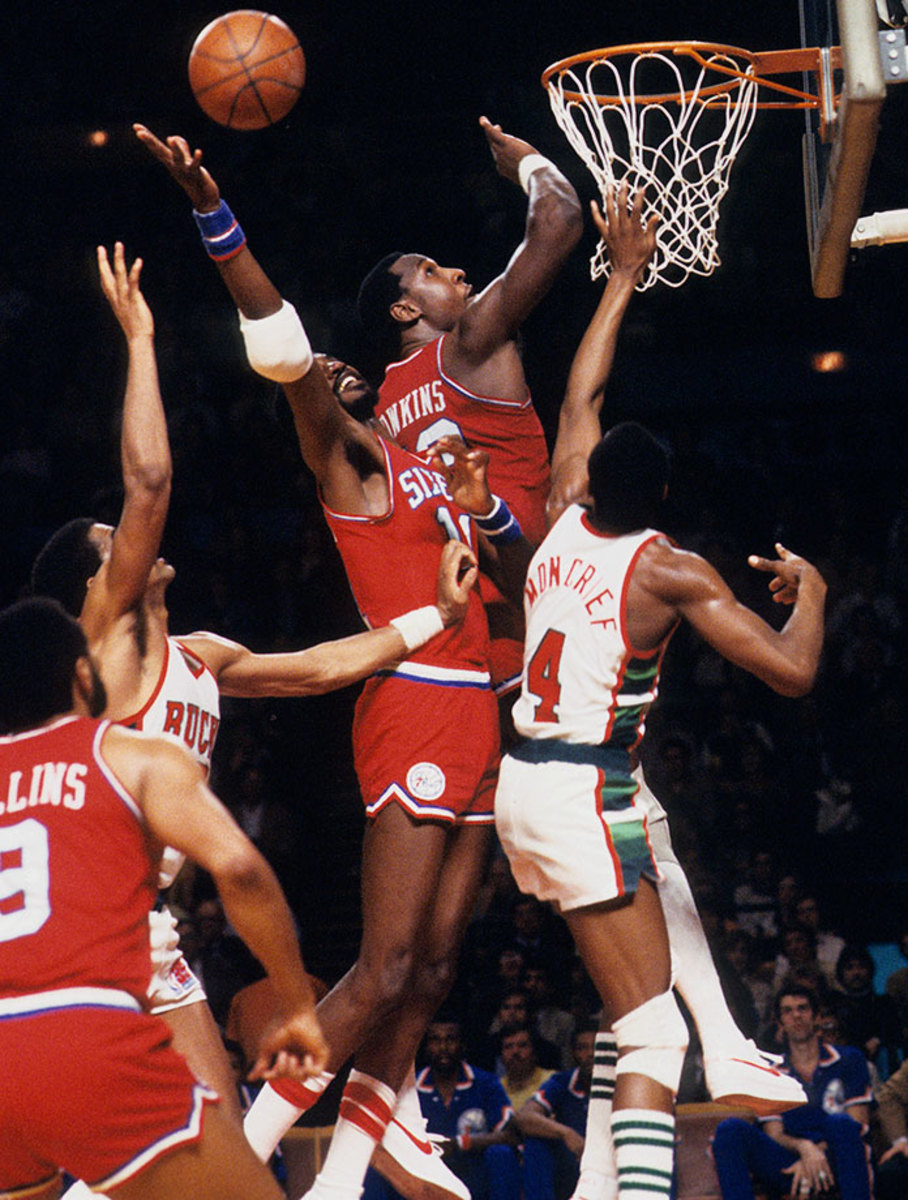

Darryl Dawkins

1984 First Round Playoffs

Darryl Dawkins

January 4, 1986

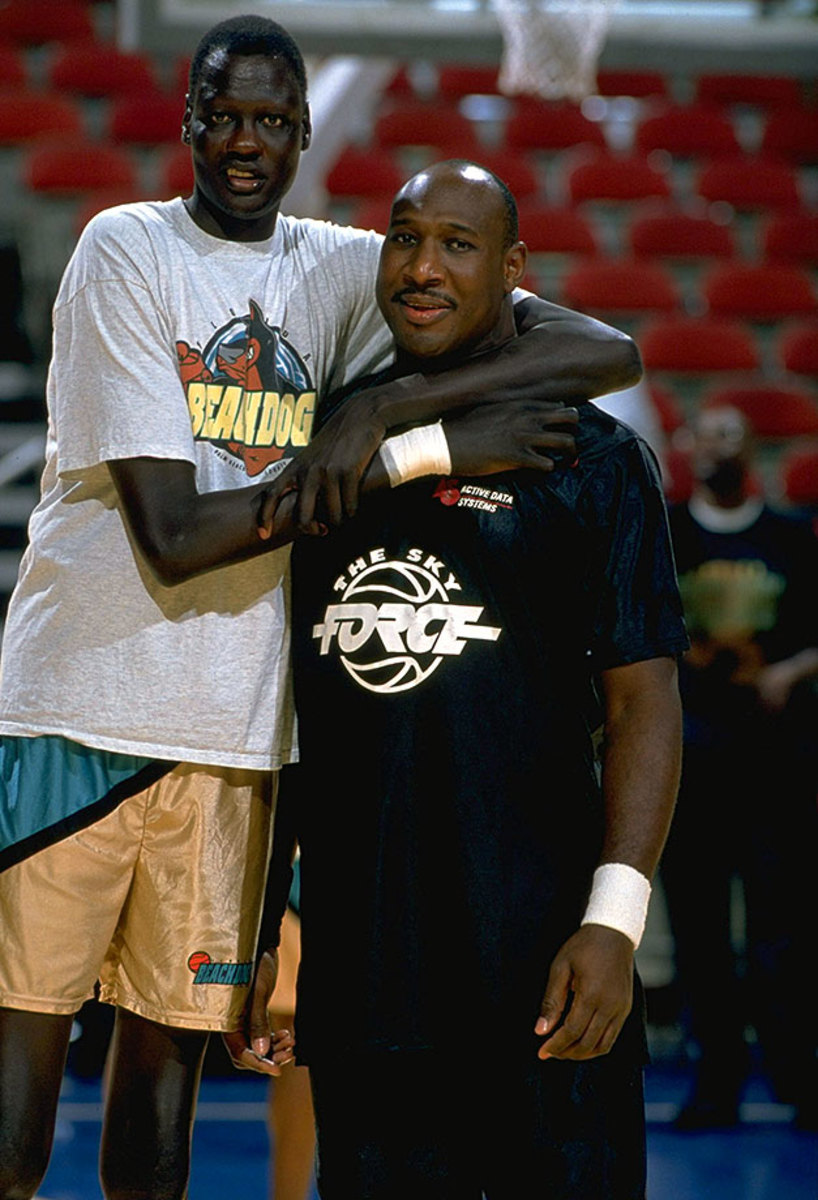

Darryl Dawkins and Manute Bol

December 6, 1995 — Continental Basketball Association: Florida Beachdogs vs. Sioux Falls Skyforce

Darryl Dawkins and Manute Bol

December 6, 1995 — Continental Basketball Association: Florida Beachdogs vs. Sioux Falls Skyforce

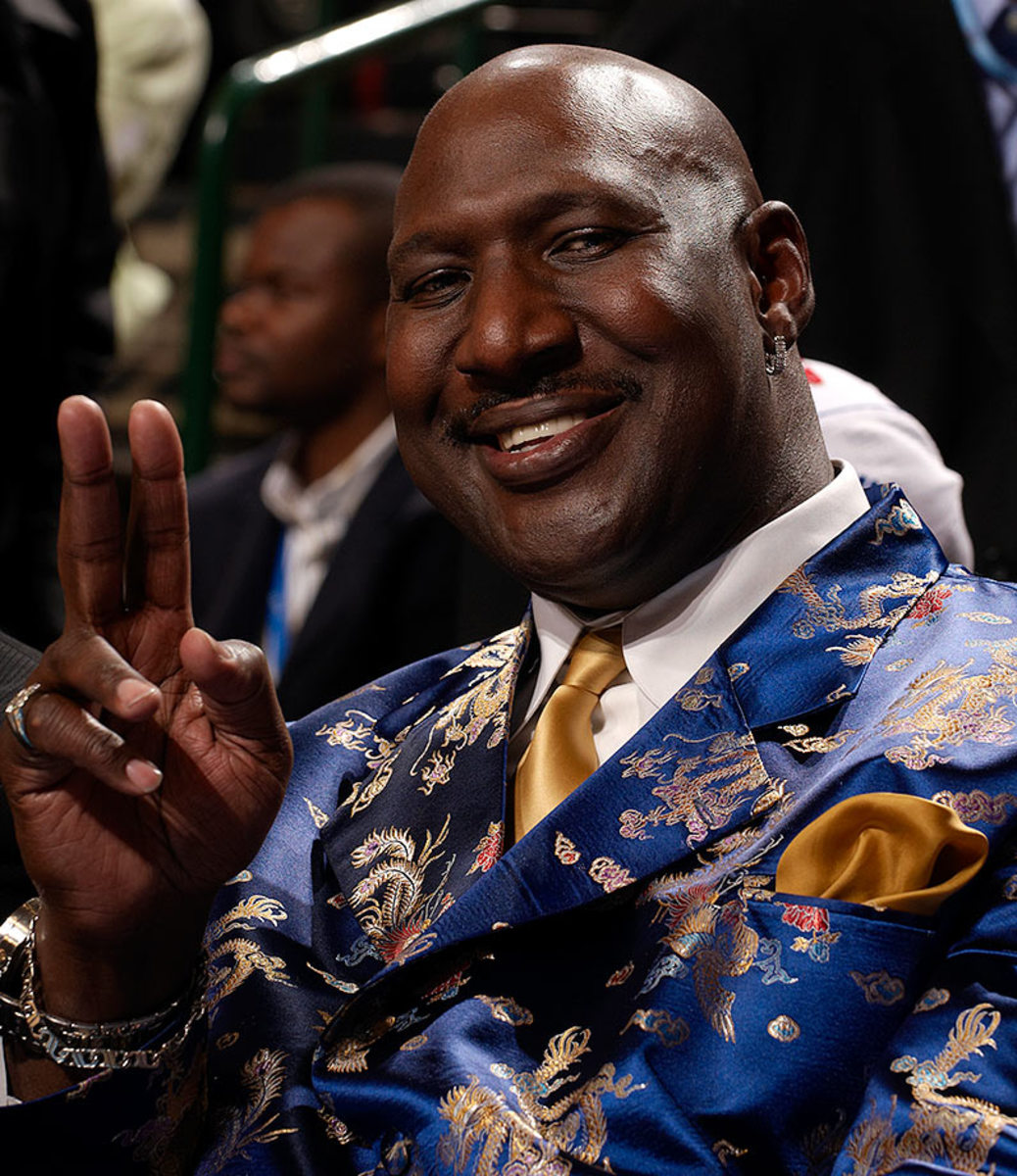

Darryl Dawkins

February 13, 2010 — NBA All-Star Saturday Night

Dawkins's imagination was wondrous. He could entertain with tales of interplanetary space travel or, on a moment's notice, deliver a lecture on the definition of funk—not Neil. He had a larger-than-life personality and the timing of a stand-up comic. One moment he would be talking seriously with Collins about his wish to get married and start a family, and a moment later he would walk outside the locker room and announce to the waiting throng that he was throwing a party and every woman in the city of Philadelphia was invited.

Funk believes Dawkins utilized this kind of behavior as a shield. "Darryl was scared that he wasn't going to be everything that people projected him to be," Funk says. "To relieve some of that pressure he hid behind his outrageous personality. What 20-year-old wouldn't be scared in that situation?" Though reluctant to admit it, when pressed, Dawkins will confess to the fear. "Yeah, sometimes it scared me a little." he says. "I didn't know what else I could do to satisfy everyone. Everyone always expected more."

Especially the 76ers. They reached the NBA finals three times during Dawkins's years in Philadelphia, but gradually management's patience faded, and he was traded, in 1982 at age 25, to the New Jersey Nets.

"Darryl, do you know where they signed the Declaration of Independence?"

"Of course. At the bottom," responded Double D.

The trade to New Jersey left Dawkins with the feeling that his career was bottoming out. He had parted on bitter terms with 76ers owner Harold Katz, who made no secret of his belief that Darryl just did not consistently work hard enough for the money he was being paid. Dawkins, who had come back after breaking a leg during the season to participate in the playoffs, thought the gesture was proof enough of his heart.

In New Jersey he went through four coaches in five years, including myself in his last two seasons. He had both his best and his worst seasons with the Nets.

He either played well or was recovering from injuries; as always there seemed to be no happy middle ground for him. In 1984-85, after what Don Nelson thought would be the turning point in Dawkins's career, he suffered a back injury and missed 43 games.

The year after that, my first as a head coach, Dawkins got off to a great start and then had a back injury necessitating the first of two operations to repair disk problems. A measure of Dawkins's value to that team: With him in the lineup our record was 29-22; without him we were 10-21.

Having played against Dawkins during my last three years as a player with Houston and New Jersey and now having coached him, I have seen him come full circle. In writing this story I have listened to all the opinions, excuses and reasons for why his career has turned out the way it has. And many times I agreed with what was being told me because I had gone through similar experiences with Dawkins.

Yet, trying to define Darryl Dawkins is difficult indeed. There are so many different Darryl Dawkinses, and each seems inconsistent with the others.

There is the man who shows enormous love and care for his family. He has bought homes for both his mother and grandmother. He supports other family members.

There are the hours during the Christmas holidays when he gladly tours the children's and veterans' wards of local hospitals, looking as if being there gives him more pleasure than it does those he visits.

Kids flock to him at games, at summer clinics or just in the street. He never turns them away. He is a master at drawing them out, telling them they must owe him some money, don't they? He gives them nicknames that make them giggle.

When Free was lying on the floor after being injured in a playoff game in 1977, Dawkins was so concerned about his friend that he picked him up in his arms and carried him all the way to the dressing room, as though Free were his little brother. Yet when Dawkins thought his teammates did not back him up sufficiently during a fight with Maurice Lucas in the second game of the '76-77 NBA finals against the Portland Trail Blazers, he was so enraged that he tore lockers from the walls, caved in a toilet stall and barricaded the door so that the team could not get back into the dressing room in the Spectrum.

There were other sides to his personality. He says he had problems with his first two business agents, which left him bitter. Eventually he wound up owing the IRS a great deal of money and had a lien slapped on his salary, and the bank that held the mortgage on the house he bought for his mother threatened foreclosure. He sometimes refuses to pay small debts. Lewis Schaffel, the former Nets chief operating officer, recalls, "I could call him up at the last minute to do a clinic, and he would always come. But if he owed you five dollars, you could never find him."

He was equally hard to figure on the court. I congratulated him once when he got 10 rebounds. He looked up and said, "Thanks, but don't expect that tomorrow night." He was afraid that if he kept performing at a high level, everyone would expect it and sooner or later he would disappoint them.

The list of stories about Dawkins—funny or sad or compassionate or interplanetary—is endless, but the stories are camouflage. They obscure the big question: Why wasn't Dawkins great? Erving says, "Darryl wasn't driven to be the greatest basketball player ever. Knowing him, that was probably for the best. His personality might not have let him deal well with that level of success." Erving recalls his own days at the top of the ABA: "There were many times I wanted to run for cover. There were definitely times it became overwhelming."

Were the expectations for Dawkins impossibly high? Mike Schuler, who worked as an assistant under Larry Brown in New Jersey and who now coaches the Portland Trail Blazers, thinks so. "Sometimes we coaches are our own worst enemies. We see every single wart and are so critical of our own players," he says. "Few players will ever live up to our expectations. We just expect too much."

GALLERY: Best NBA players ever by jersey number

Best NBA Players by Jersey Number

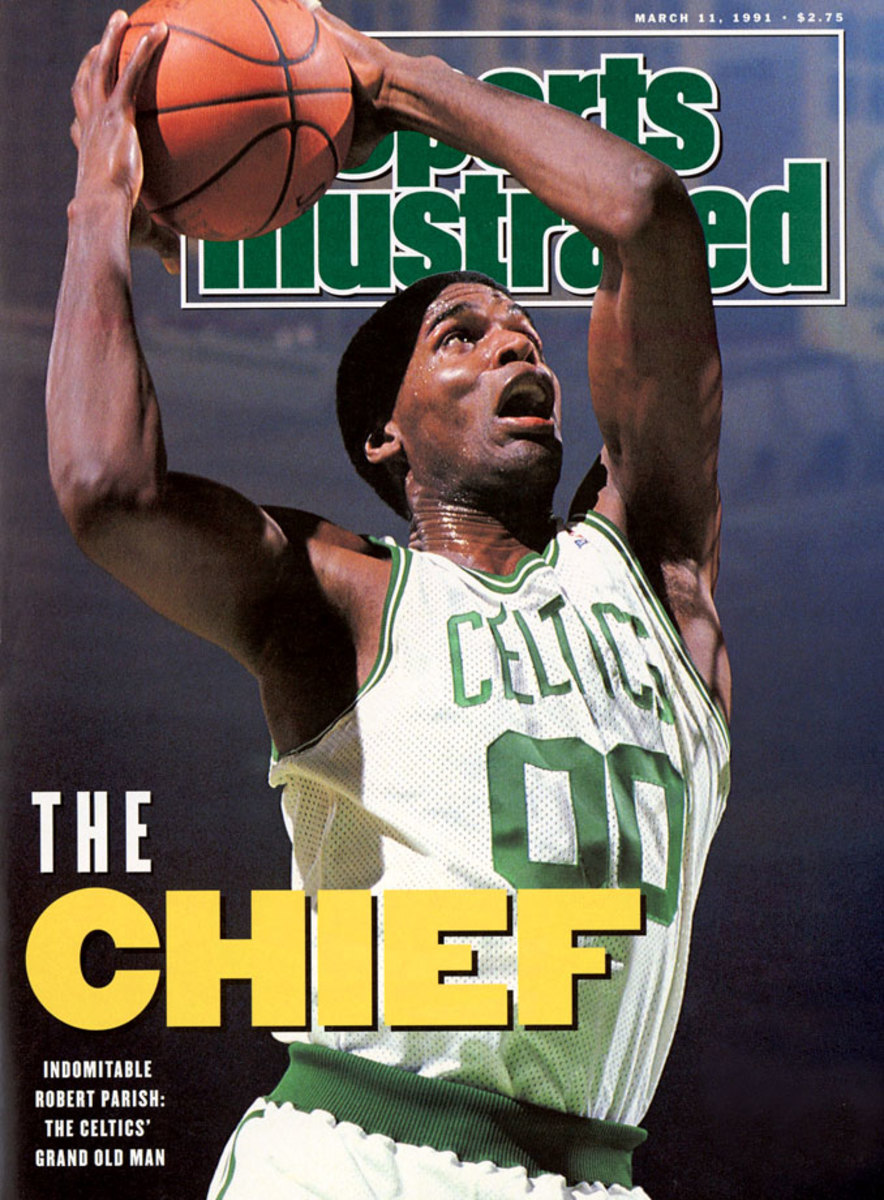

00 — Robert Parish

Best known as the defensive anchor of the Larry Bird-led Celtics teams of the 80s, Parish was also outstanding on the offensive side of the ball, a smooth jump shooter who hit at a nearly 54% clip from the floor in his 21-year career and averaged 14.5 points. A four-time NBA champion and nine-time All-Star, Parish’s athletic ability and utility on both ends as a 7-foot center foreshadowed the direction in which his position would head decades later.

0 — Russell Westbrook

The best may still be to come for Westbrook, Oklahoma City’s dynamic point guard who continues to reshape his position and push the limits after a career season in 2014-15. At 26, Westbrook averaged 28.1 points, 8.6 assists and 7.3 rebounds, single-handedly carrying the Thunder when they needed it most. With Kevin Durant returning to the fold, Westbrook’s numbers may dip, but his efficiency could improve accordingly. His all-around game gives him the nod over Arenas. — Runner-up: Gilbert Arenas

1 — Oscar Robertson

Everyone knows the Big O is the only player in NBA history to average a triple-double for an entire season. What’s lost is the specific stats from Robertson’s most incredible year, in which he posted nightly figures of 30.8 points, 12.5 rebounds and 11.4 assists at age 23, just his second season in the league. — Runner-up: Tracy McGrady

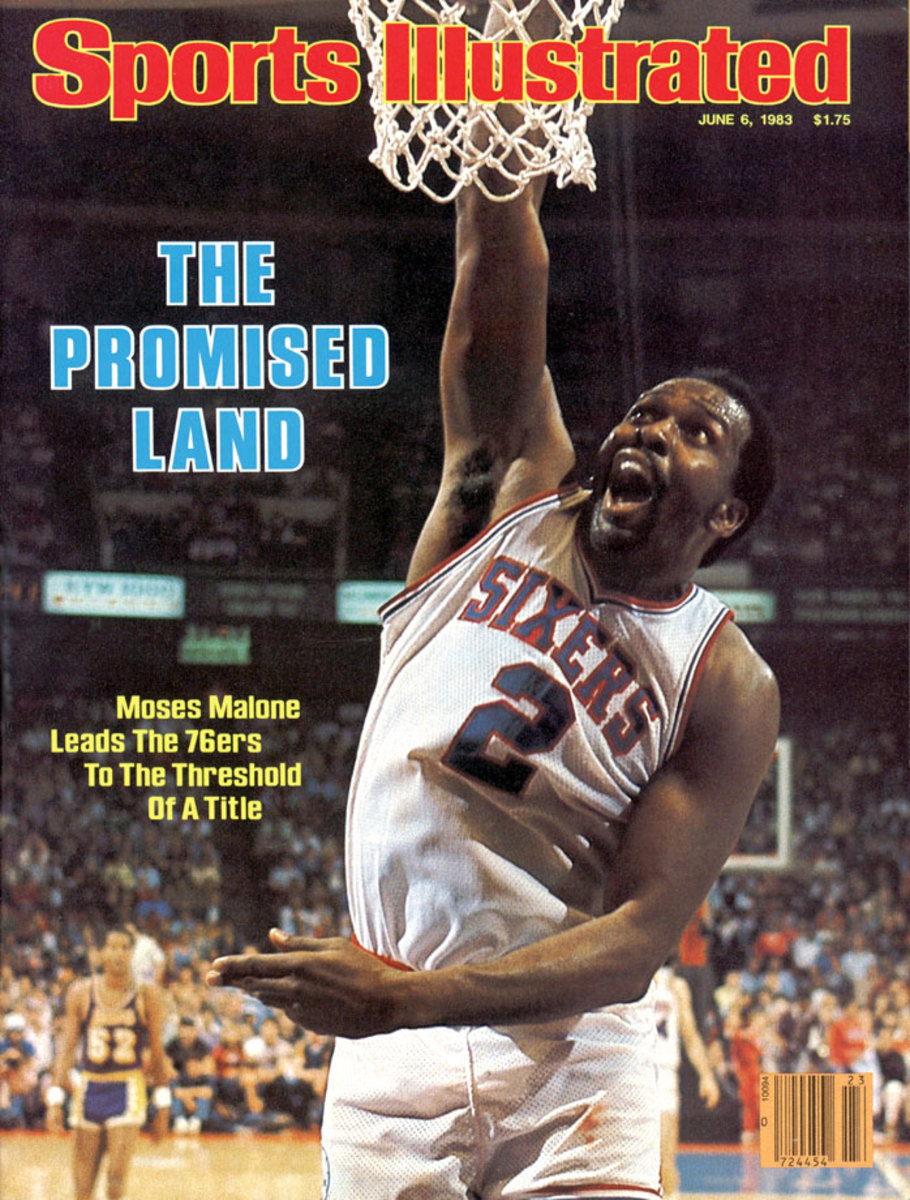

2 — Moses Malone

Malone was a statistical behemoth, averaging a double-double as a rookie and never looking back while making several stops around the NBA. A three-time MVP, Malone peaked as a Rocket with a 31.1 point, 14.7 rebound campaign in 1982, the year before signing with the Sixers and subsequently leading them to the ‘83 title as Finals MVP.

3 — Dwyane Wade

Before Wade annually sat out half of each season to rest and nurse injuries, “Flash” was one of the most electric players in the league. It takes a special player to lead an NBA franchise to its first championship in just his third season. Wade also played at an MVP level over the course of his 2008-09 campaign. — Runner-up: Allen Iverson

4 — Adrian Dantley

Dantley was one of the league’s most explosive scorers for a long time, making six All-Star games and stringing together four straight 30-plus point-per-game seasons in the early ‘80s, twice leading the league in scoring. Though he almost never shot three-pointers, Dantley finished his career with an average of 24.3 points per game on 54% shooting, working creatively to get buckets from the midrange and around the rim. — Runners-up: Joe Dumars, Dolph Schayes

5 — Kevin Garnett

Anything was possible for defenses anchored by Garnett in his prime. One of the greatest prep-to-pro cases of all time and a perennial All-Star and All-NBA selection, Garnett transcended the game with his intensity and antics. Whether getting on all fours to bark like a dog or banging his head against the stanchion, KG always made his presence felt. — Runner-up: Jason Kidd

6 — Bill Russell

Though another No. 6 continues to make his case in Cleveland, Bill Russell’s 11 championship rings in 13 seasons are impossible for all but the most irrational to argue against. No athlete in the history of major team sports has ever sustained individual dominance and team success quite like Russell, who retired at age 34 before transitioning into coaching and leading Boston to two more titles––like clockwork. — Runner-up: LeBron James

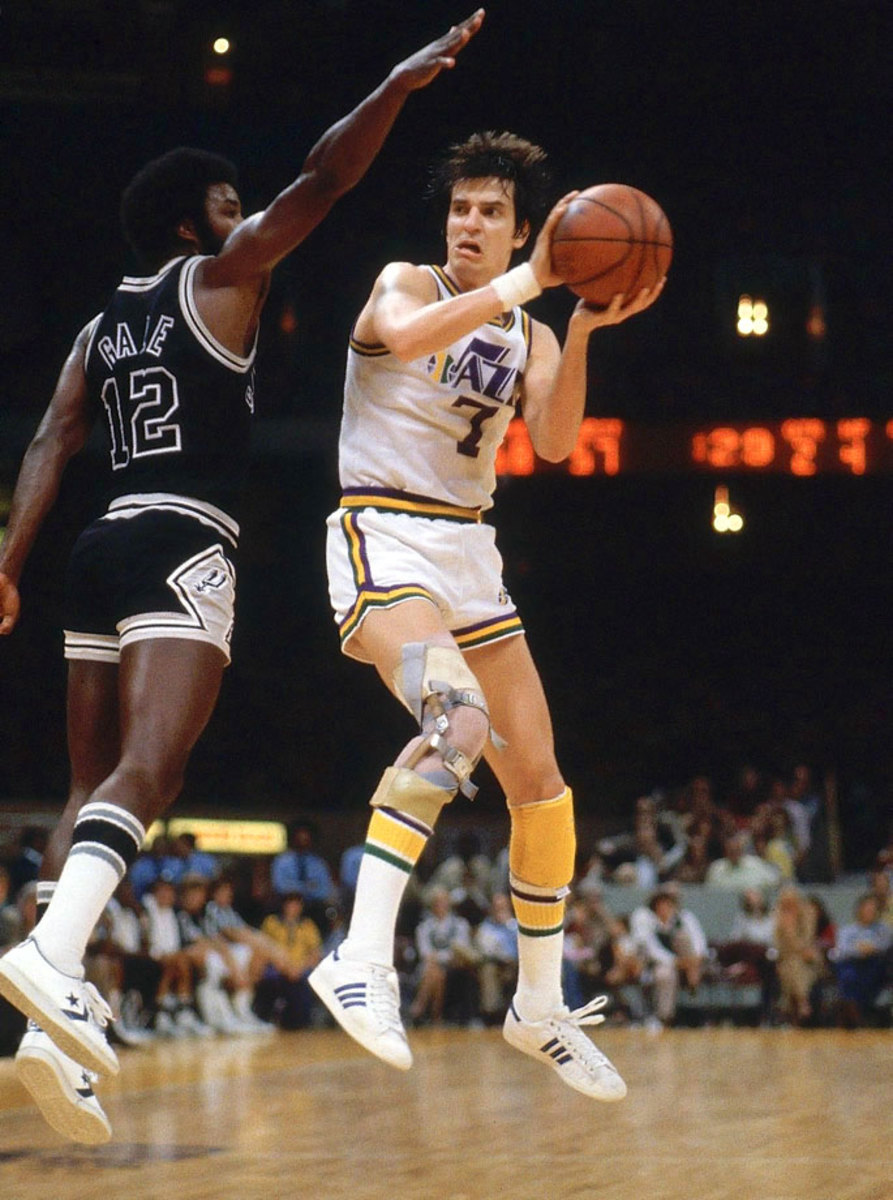

7 — Pete Maravich

One of the NBA’s greatest scorers and the all-time leading scorer in NCAA history, “Pistol Pete” put up points in style. Ever the showman, Maravich brought a streetball-style game to the NBA. His flashiness helped build basketball’s popularity in the city of New Orleans before the Jazz moved to Utah. — Runners-up: Kevin Johnson, Carmelo Anthony

8 — Kobe Bryant

Younger basketball fans may not remember Kobe Bean donning No. 8 early in his career, but the results were prolific, peaking in 2005-06 when he averaged 35.4 points per game. Before there was No. 24 Kobe, the older and wiser Mamba we now know, there was the dynamic slasher who won three titles alongside Shaquille O’Neal, demanded the ball just as much, and demolished defenses in the process.

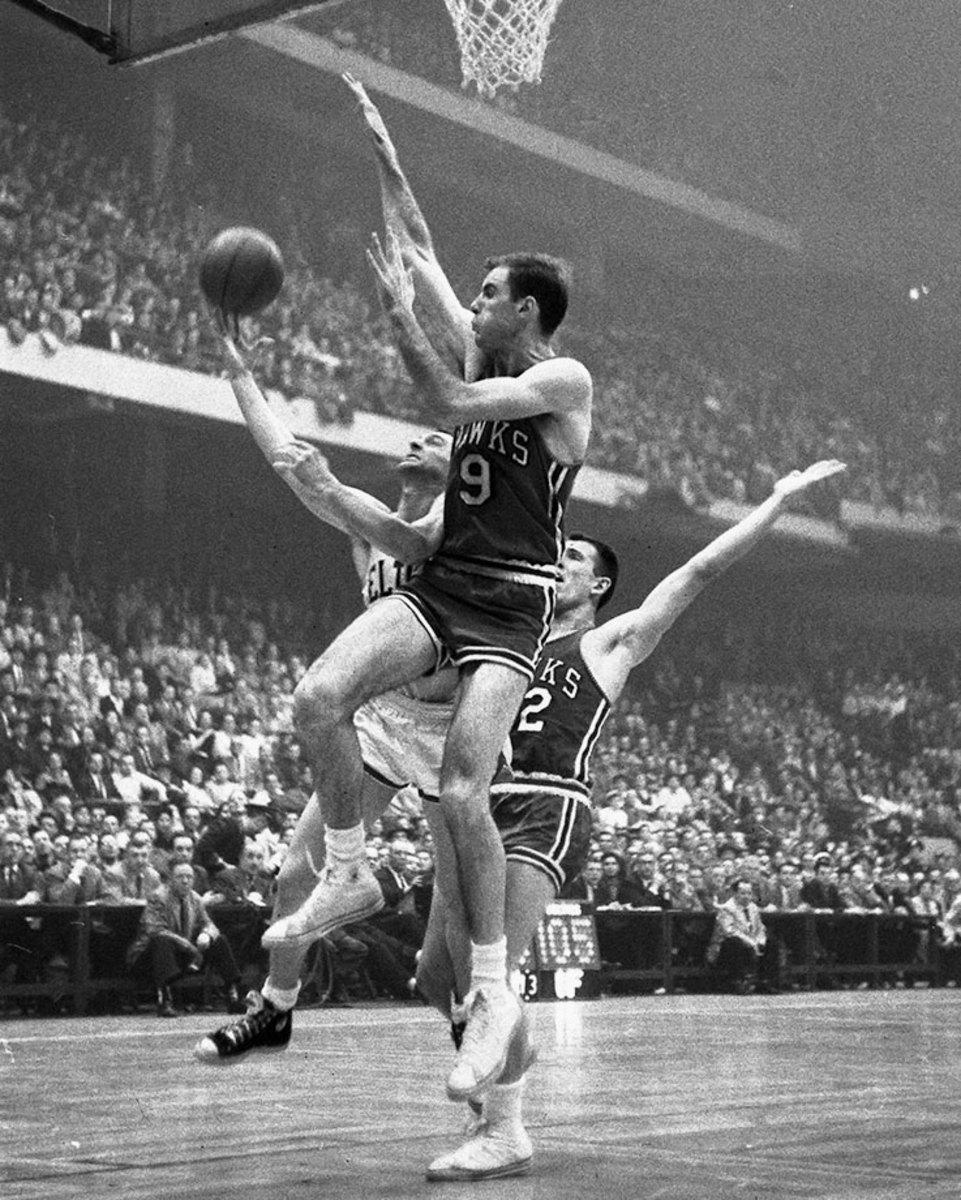

9 — Bob Pettit

The St. Louis Hawks were the only team to defeat the Bill Russell’s Boston Celtics in an NBA Finals series, with Pettit leading St. Louis to the 1958 title. Pettit took home regular season MVP honors in 1955 and 1959 and led the Hawks to four Finals appearances. He was an All-Star in each of his 11 seasons. — Runner-up: Tony Parker

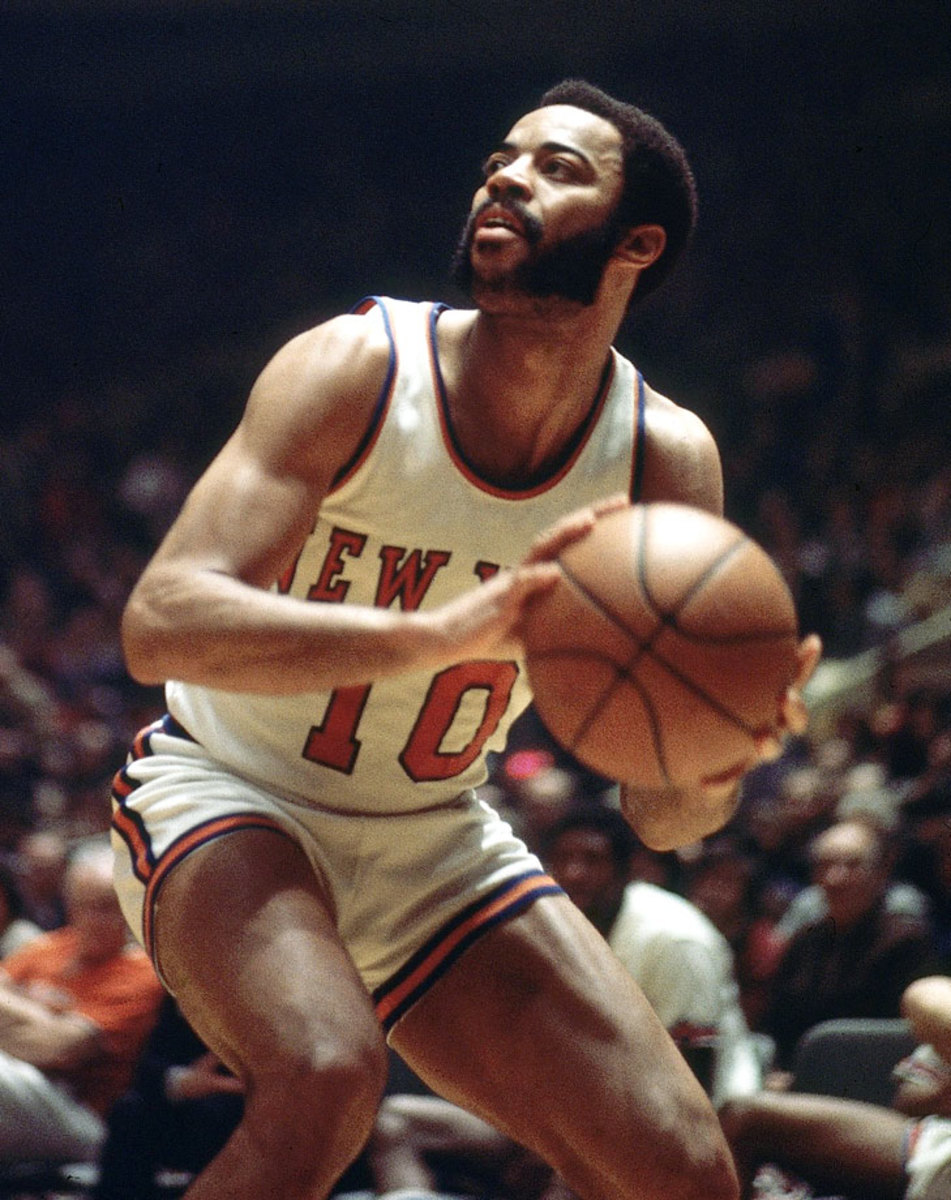

10 — Walt Frazier

Teaming with Earl “The Pearl” Monroe, “Clyde” helped bring the dazzle and New York style to the Knicks, one of the first truly effective dual-point guard combinations and one of the greatest backcourts ever. A two-time NBA champion, Frazier now sits as one of the greatest Knicks of all-time and one of the league’s most stylish men, even in retirement. — Runner-up: Tim Hardaway

11 — Isiah Thomas

Before Thomas’ front office failures, the feisty Chicago product led the “Bad Boy” Pistons to back-to-back championships in 1989 and 1990. The 12-time All-Star appeared in every mid-season classic during his career save for his final season in 1993-94. He also piloted Detroit to the playoffs in all but two of his seasons. — Runner-up: Elvin Hayes

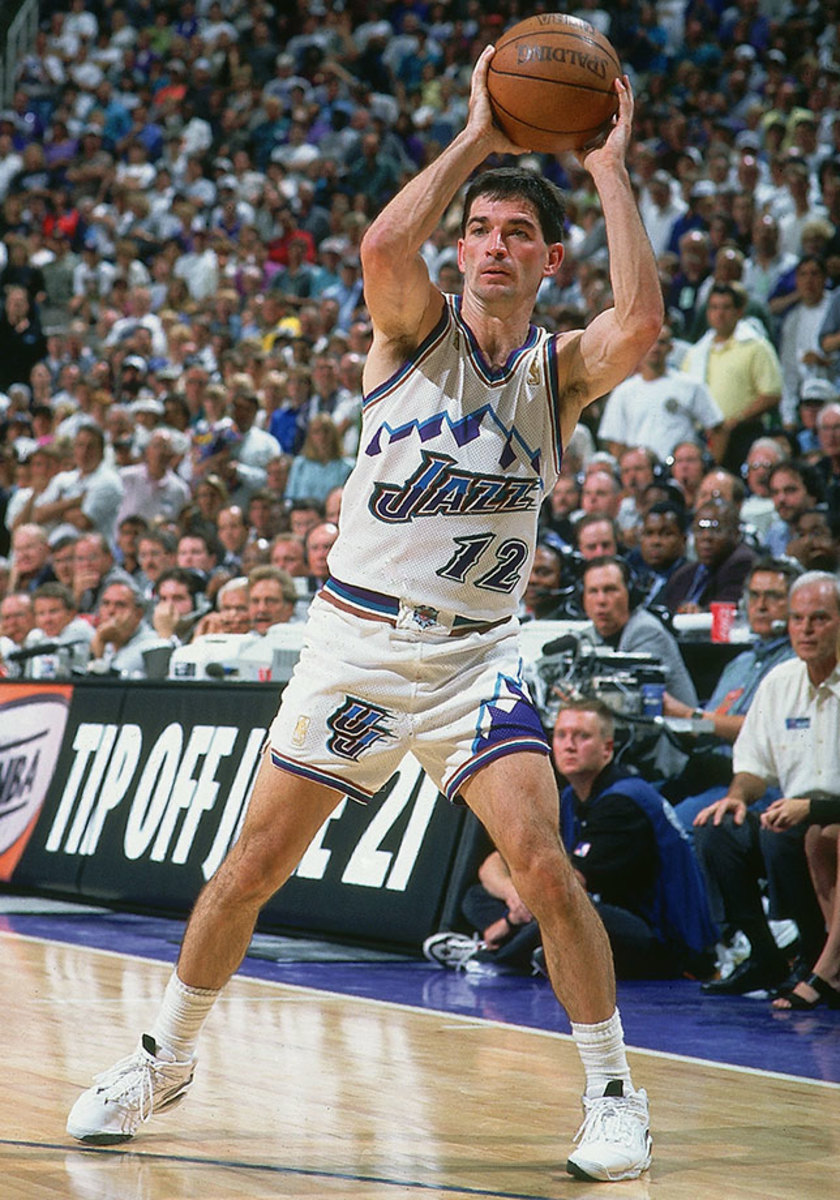

12 — John Stockton

A 10-time All-Star and half of perhaps the most prolific guard-post tandem ever, John Stockton remains the NBA’s all-time leader in assists and steals. He dominated games at a slender 6’1”, with incredible know-how, a hard-nosed approach on both ends and unbelievable consistency all the way until his retirement at age 40. For the definition of a pure point guard, look no further.

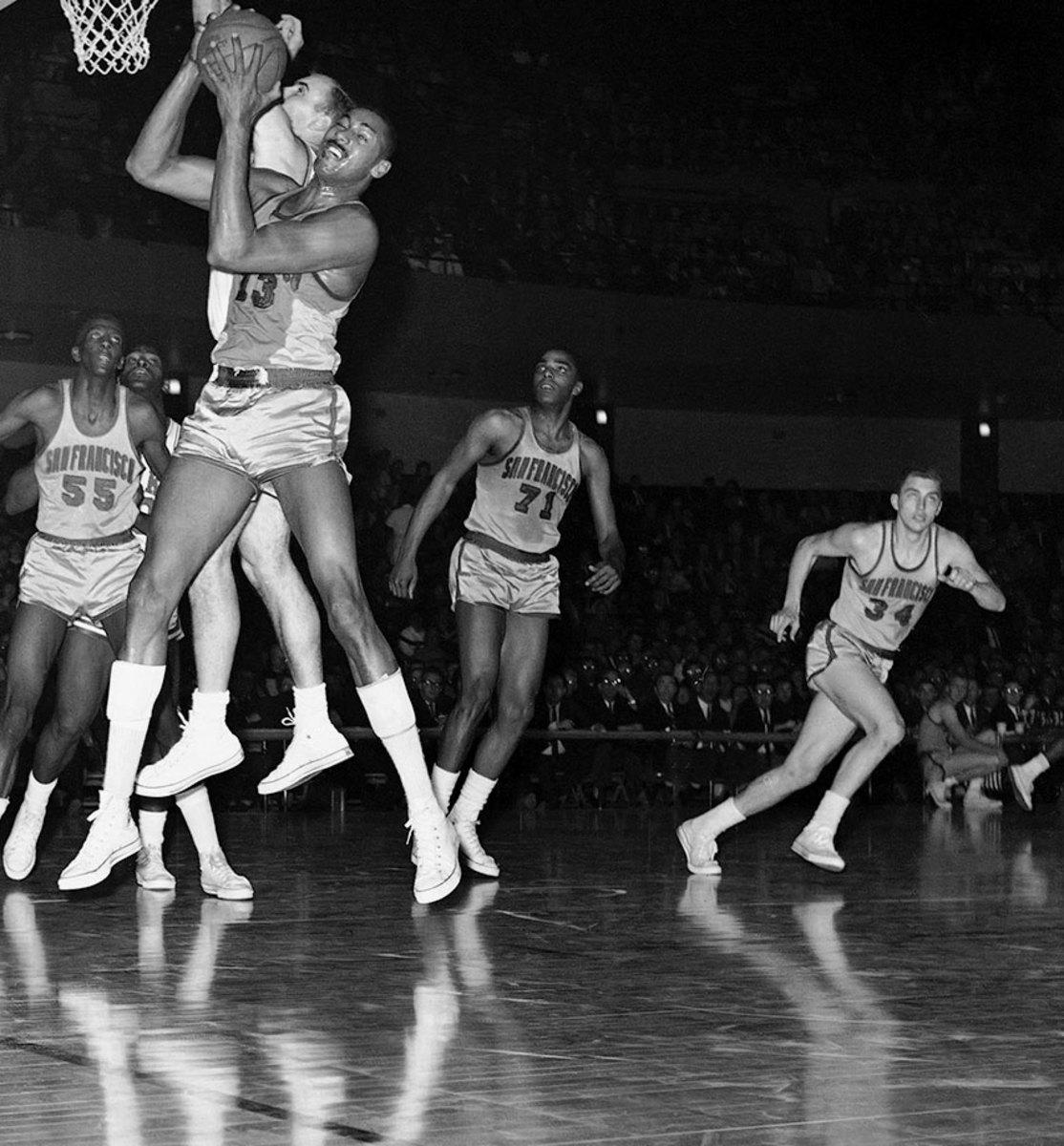

13 — Wilt Chamberlain

The Big Dipper, of course, is the only player in NBA history to score 100 points in a single game. Few players have forced the league to change the rules in order to make games fairer for opponents. The NBA had to widen the lane, institute offensive goaltending and amend the inbounding and free throw regulations because of Chamberlain. Beast mode. — Runner-up: Steve Nash

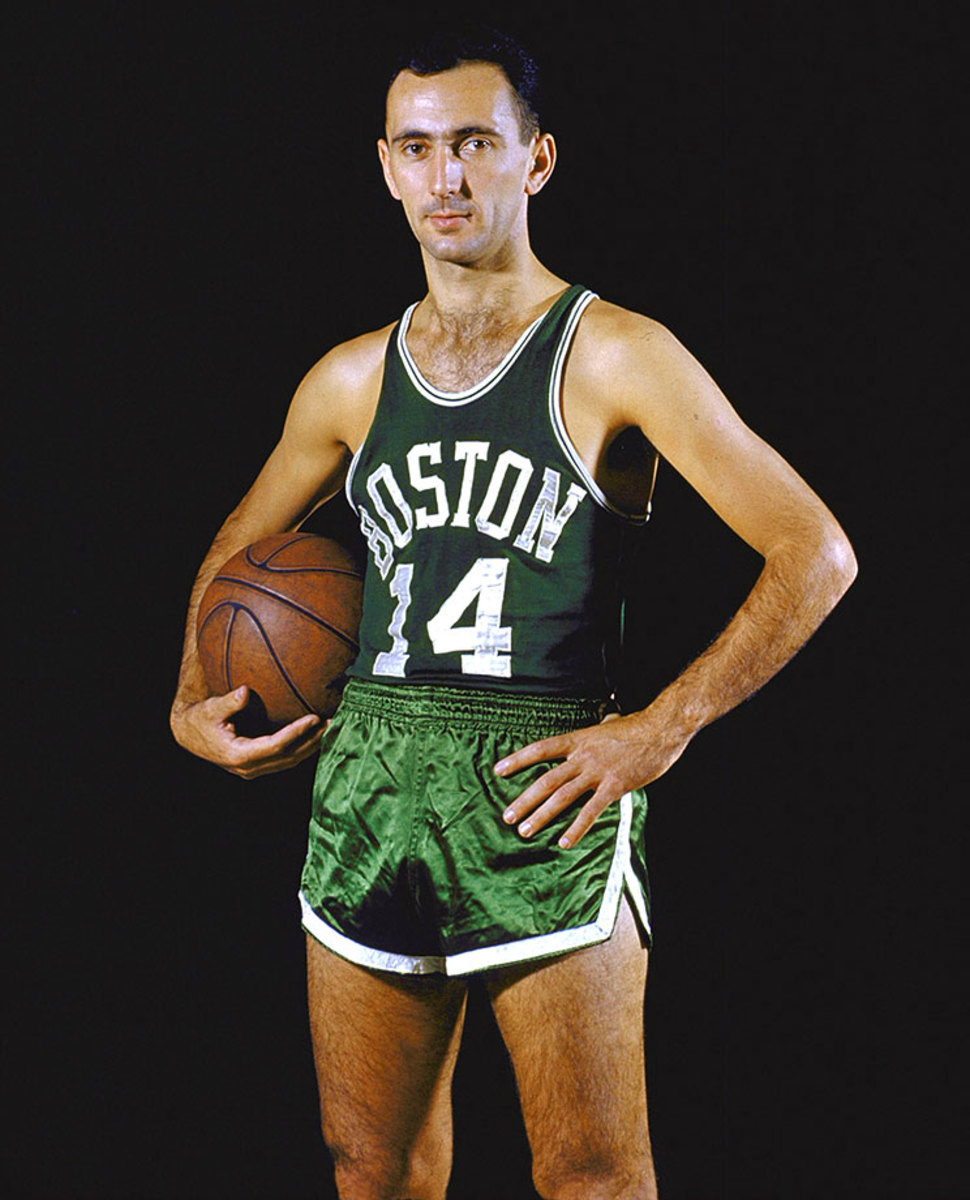

14 — Bob Cousy

An All-Star in every single one of his seasons (save for a seven-game return to boost ticket sales for the Royals, the team he coached, in 1970), Cousy was a six-time NBA champion and the 1957 MVP. He was the man in Boston until the arrival of Bill Russell, with whom he teamed to build the NBA’s first dynasty.

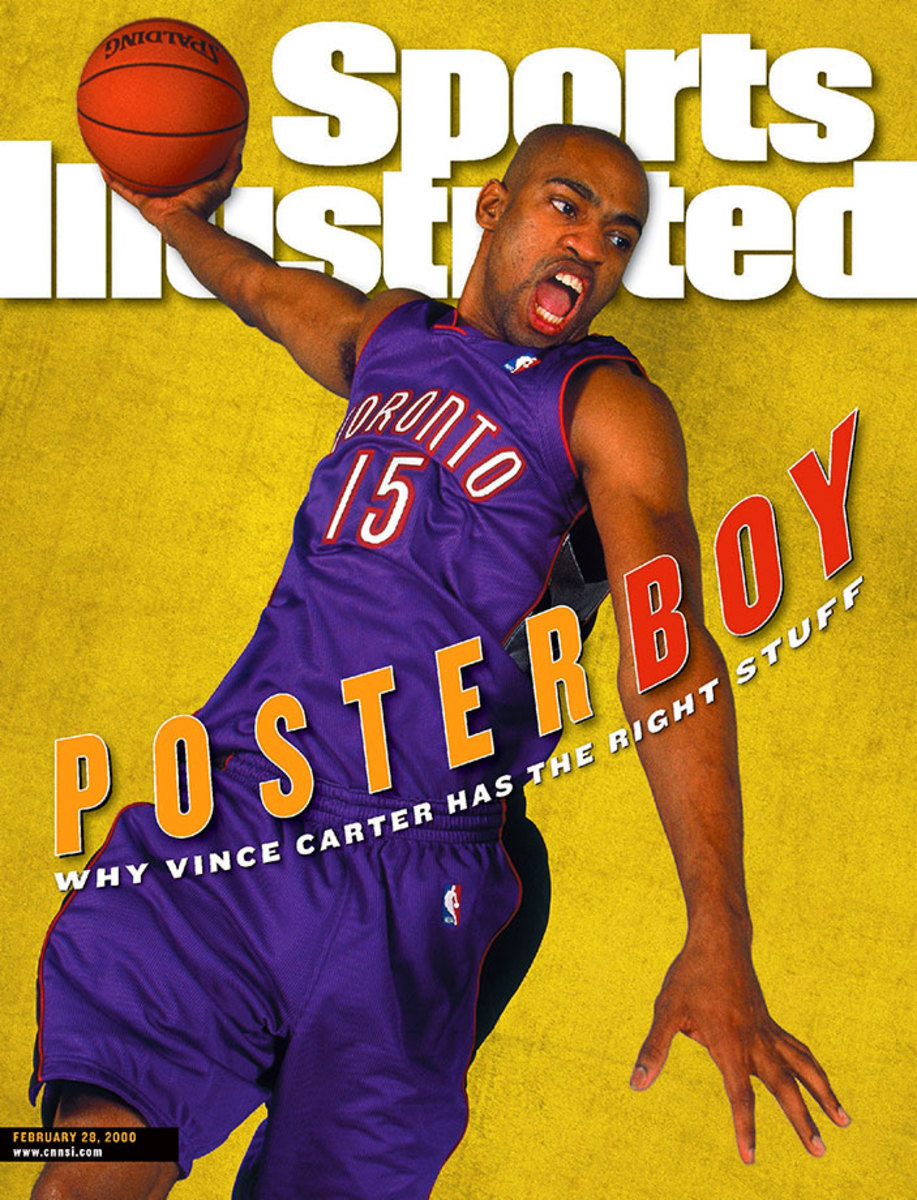

15 — Vince Carter

The reputation of “Vinsanity” for acrobatic dunks doesn’t do his overall game enough justice. Carter currently ranks 30th all-time in career scoring and will likely pass Charles Barkley in 2015-16. His incredible play was key for an upstart Toronto Raptors franchise in the early 2000s. — Runner-up: Hal Greer

16 — Bob Lanier

A force in the middle for the Pistons and Bucks, Lanier retired in 1984 with career averages of 20.1 points and 10.1 rebounds. A well-rounded post man who was a strong free-throw shooter (76.7%) and in his prime, a shot-blocker, Lanier lived up to his selection as the No. 1 pick in the 1970 draft, playing for 15 strong years and finishing with five consecutive division titles as a Buck. —Runners-up: Pau Gasol, Jerry Lucas, Cliff Hagan

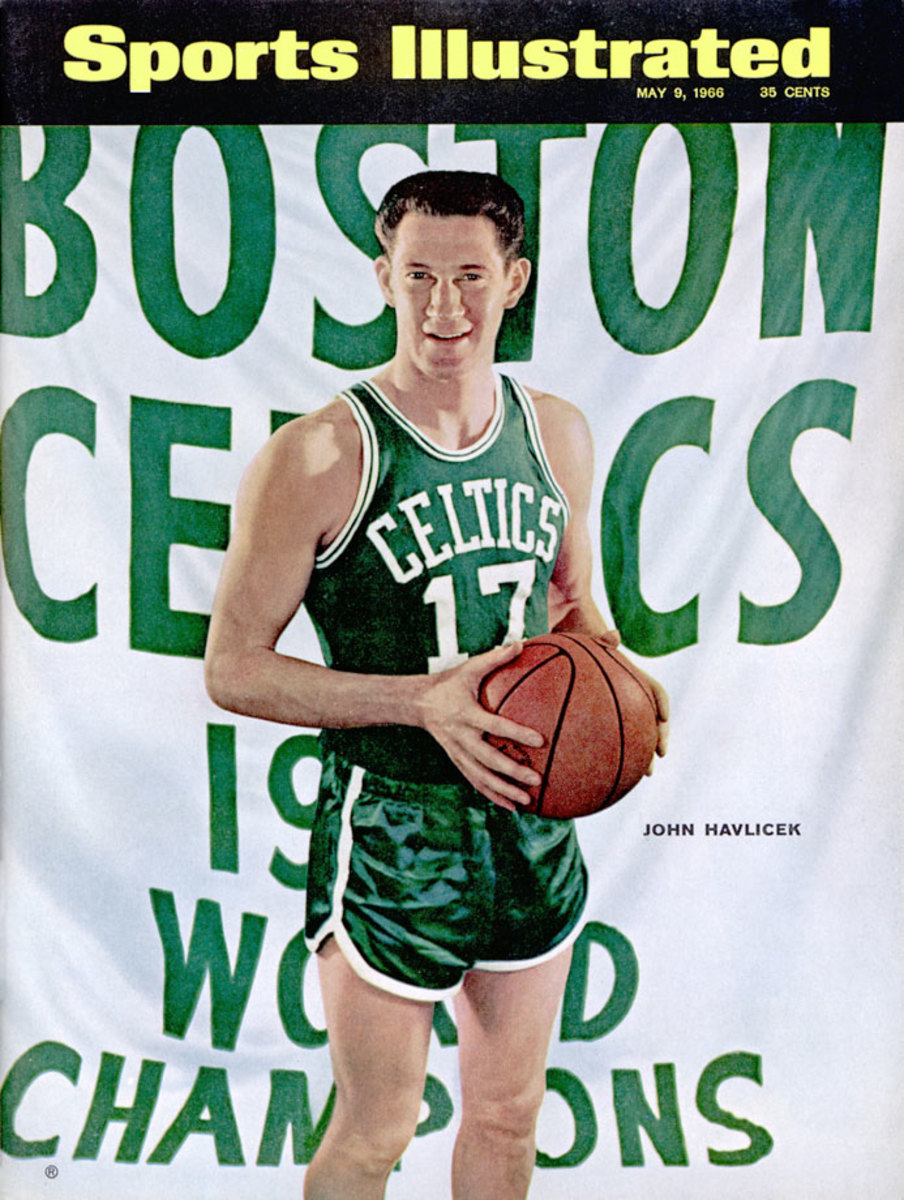

17 — John Havlicek

One of the most well-rounded players ever, Havlicek’s Celtics teams won eight championships in his 13 seasons. Hondo bridged the gap between the Bill Russell era and the Celtics’ successful run into the 1970s. In his prime, Havlicek posted numbers strikingly similar to LeBron James, averaging 28.9 points, 9.0 rebounds and 7.5 assists per game in 1970-71. — Runner-up: Chris Mullin

18 — Dave Cowens

Best known for his all-out approach on every play, Cowens was a stalwart for the Celtics in the ‘70s, winning titles in ‘74 and ‘76 and MVP honors in ‘73, on the back of a 20.5 point, 16.2 rebound campaign. Also a strong passer, Cowens retired averaging 3.8 assists per game to go with 17.6 points and 13.6 boards. An eight-time All-Star, Cowens is one of only four players (including Scottie Pippen, LeBron James and Kevin Garnett) to lead his team in points, rebounds, assists, blocks, and steals for an entire season.

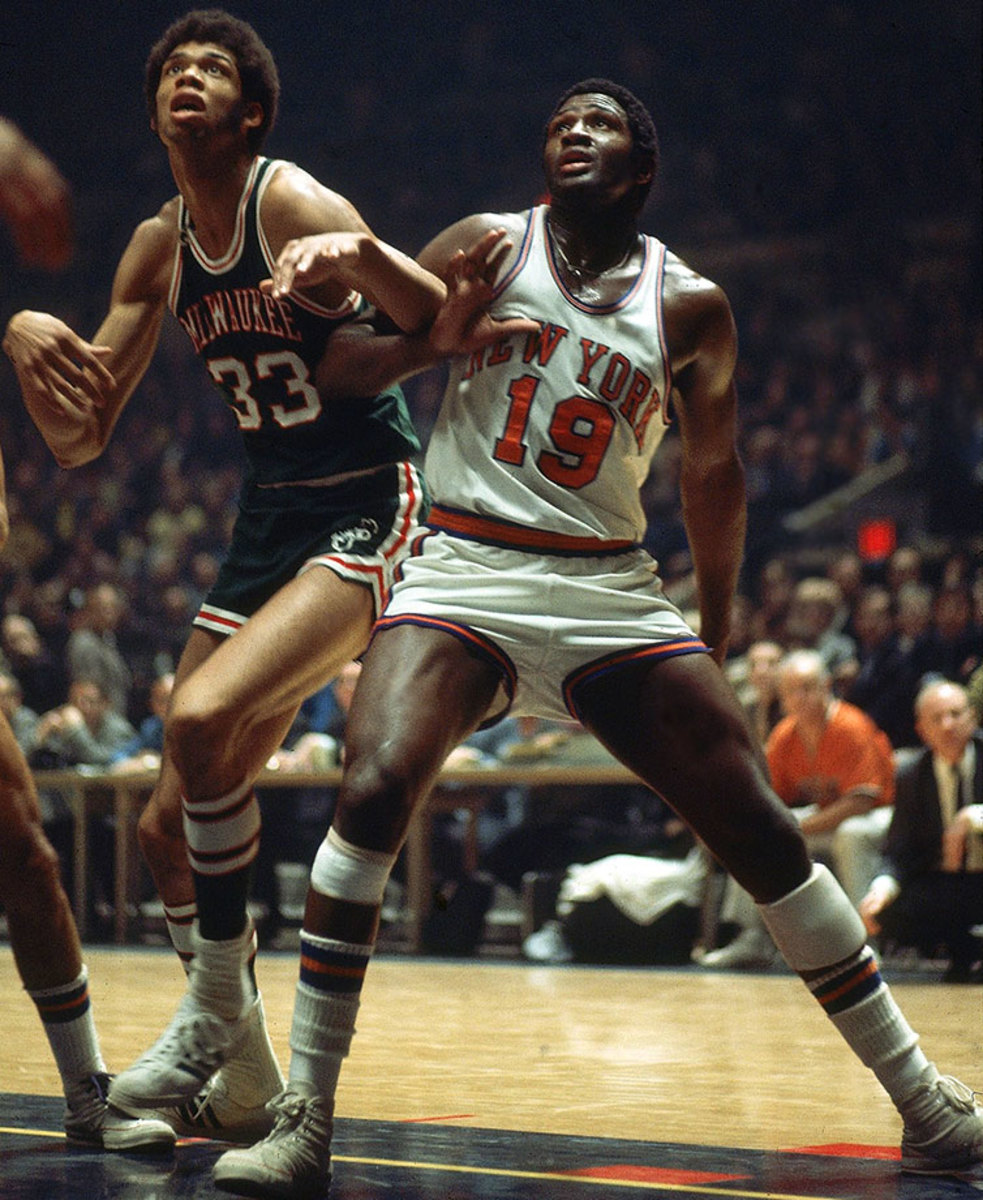

19 — Willis Reed

The Knicks haven’t won an NBA title since Reed helped clinch the 1973 championship. Reed will forever be remembered for his magical return to Game 7 of the 1970 Finals against the Los Angeles Lakers, delivering the Knicks’ first title in franchise history. He averaged 23.7 points and 13.8 rebounds per game during the 1970 playoffs. — Runner-up: Don Nelson

20 — Gary Payton

‘The Glove’ earned his nickname thanks to a reputation as the NBA’s toughest defensive point guard, bolstered by nine straight All-Defensive first team selections from 1994-2002. Payton, a nine-time All-Star, was no slouch on the offensive end, either, with a well-rounded game and the ability to create for others and get buckets when needed. One of the iconic players in the history of the Sonics, Payton would hit a huge shot as a member of the Heat in Game 5 of 2006 Finals to help Miami seize the title, his lone championship. —Runner-up: Manu Ginobili

21 — Tim Duncan

As he prepares for his 19th season, it’s hard to argue against Tim Duncan as the greatest player of his generation, bridging the gap between Michael Jordan and LeBron James. The four titles and 15 All-Star appearances are incredible on their own. Factor in his unfathomably consistent numbers and Duncan’s resume is one of the greatest all-time. Period. — Runner-up: Dominique Wilkins

22 — Elgin Baylor

One of the NBA’s first high-flyers, Baylor was an unbelievable scorer in the pre three-point era, averaging 38.3 points per game in 1962. The 11-time All-Star appeared in eight NBA Finals but never won a title, retiring due to chronic knee problems in 1972 —a year in which Los Angeles finally won it all (he was given a ring at the end of the season anyway.) He holds the record for points scored in an NBA Finals game, with 61 in Game 5 in 1962. —Runner-up: Clyde Drexler

23 — Michael Jordan

Six championships. Five regular season MVPs. Countless All-NBA and All-NBA defensive selections. The most famous sneaker line in history. Gravity-defying dunk contest victories. The list goes on and on and on and on for the current majority owner of the Charlotte Hornets. Michael Jordan is the G.O.A.T., friends. — Runner-up: LeBron James

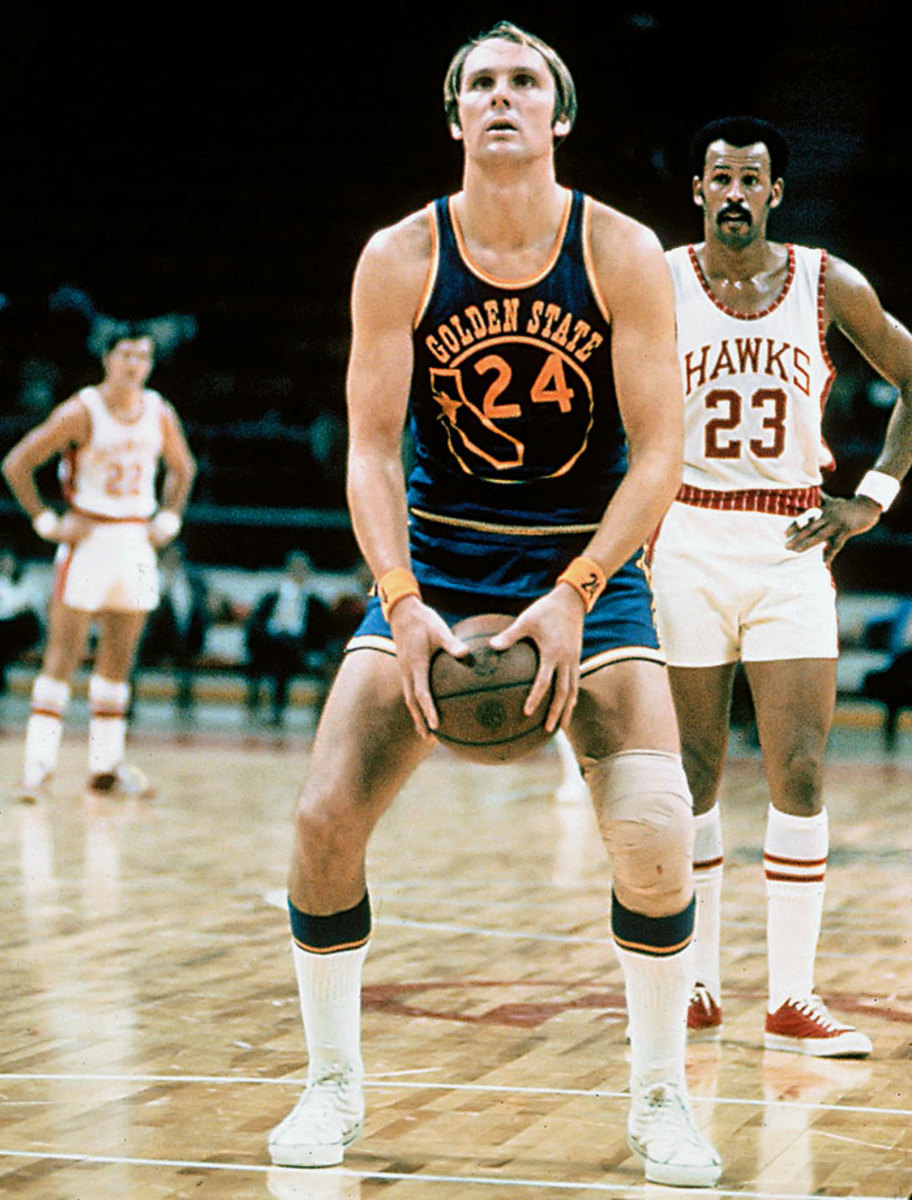

24 — Rick Barry

Beyond pioneering the granny-style free throw, Barry was one of the league’s most dominant scorers of all-time, an eight-time All-Star and the 1975 Finals MVP. He spent four seasons from 1968-1972 playing in the ABA (over which he averaged 30.5 points), which places a hit on his all-time totals, but he retired with NBA averages of 23.2 points, 6.5 rebounds and 5.1 assists (and 90% from the foul line). — Runners-up: Bobby Jones, Sam Jones

25 — Mark Price

One of the greatest free throw shooters in NBA history (a 90.4% career mark), Price doesn’t get enough credit for his overall game. A four-time All-Star, Price led the Cleveland Cavaliers for nearly a decade, running an efficient offense and posting a double-double, 16.9 points and 10.4 assists per game in the 1990-91 season. — Runners-up: Gail Goodrich, Doc Rivers

26 — Kyle Korver

One of the league’s top three-point snipers, Korver just completed an incredible All-Star campaign with Atlanta, shooting 49.2% from deep as a key cog in a diverse offense. His acumen from outside gives him the nod here at No. 26.

27 — Jack Twyman

A six-time All-Star, Twyman scorched opponents in the late 1950s and early 1960s, averaging 19.2 points per game during his 11-year career. He hung 31.2 points per game in the 1959-60 season. Twyman trails only Oscar Robertson for most career points in franchise history. The Royals are now the Sacramento Kings. — Runners-up: John Johnson, Joe Caldwell

28 — Arron Afflalo

Afflalo has been a steady, useful two-way player eight seasons into his career, peaking in 2013-14 with Orlando where he put up 18.2 points and shot 42.7% from three. The UCLA product and Compton native also famously inspired a song by rapper Kendrick Lamar. He begins next season as a Knick.

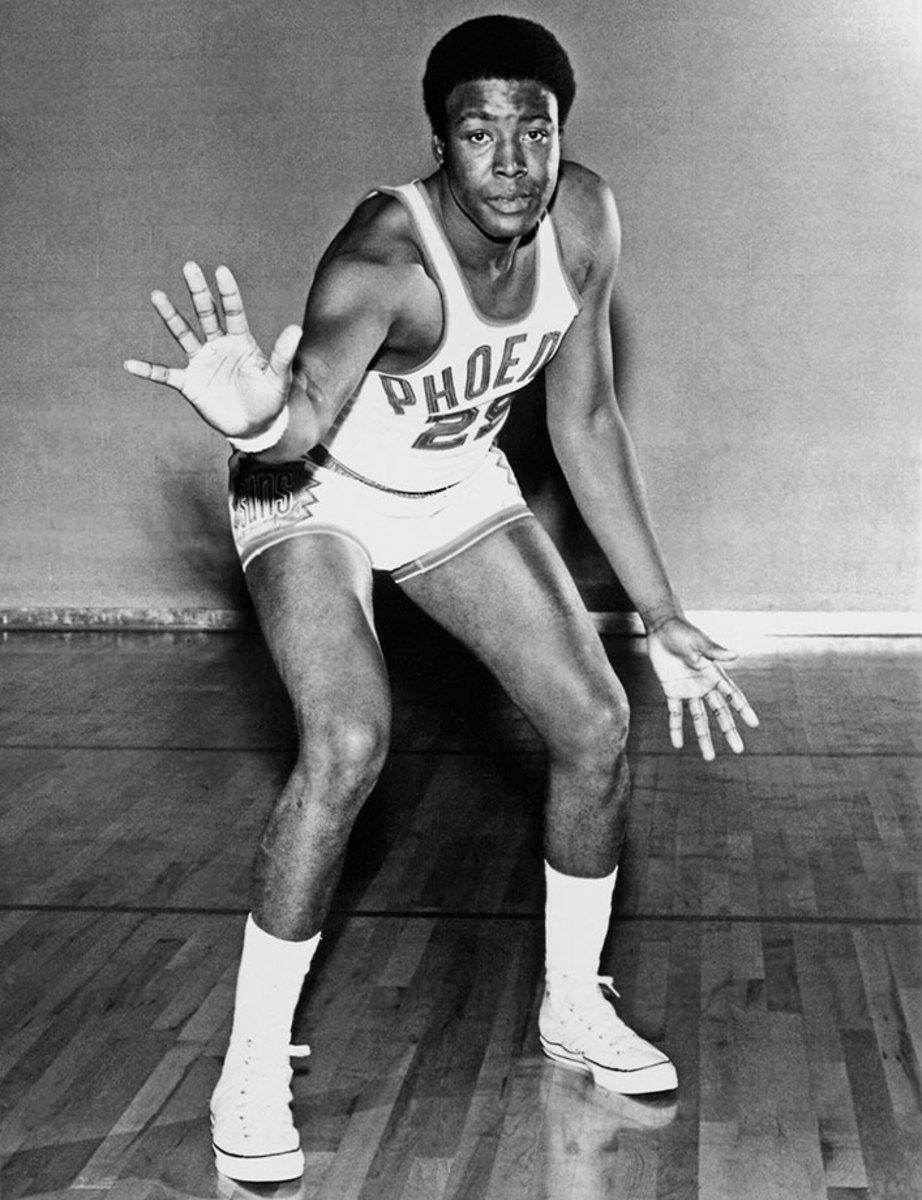

29 — Paul Silas

A two-time All-Star, Paul Silas played in three different decades and won three NBA championships (two with the Boston Celtics and one with the Seattle Supersonics). At just 6’7”, Silas was one of the best rebounders of his era, leading the NBA in offensive boards per game in the 1975-76 season. — Runner-up: Pervis Ellison

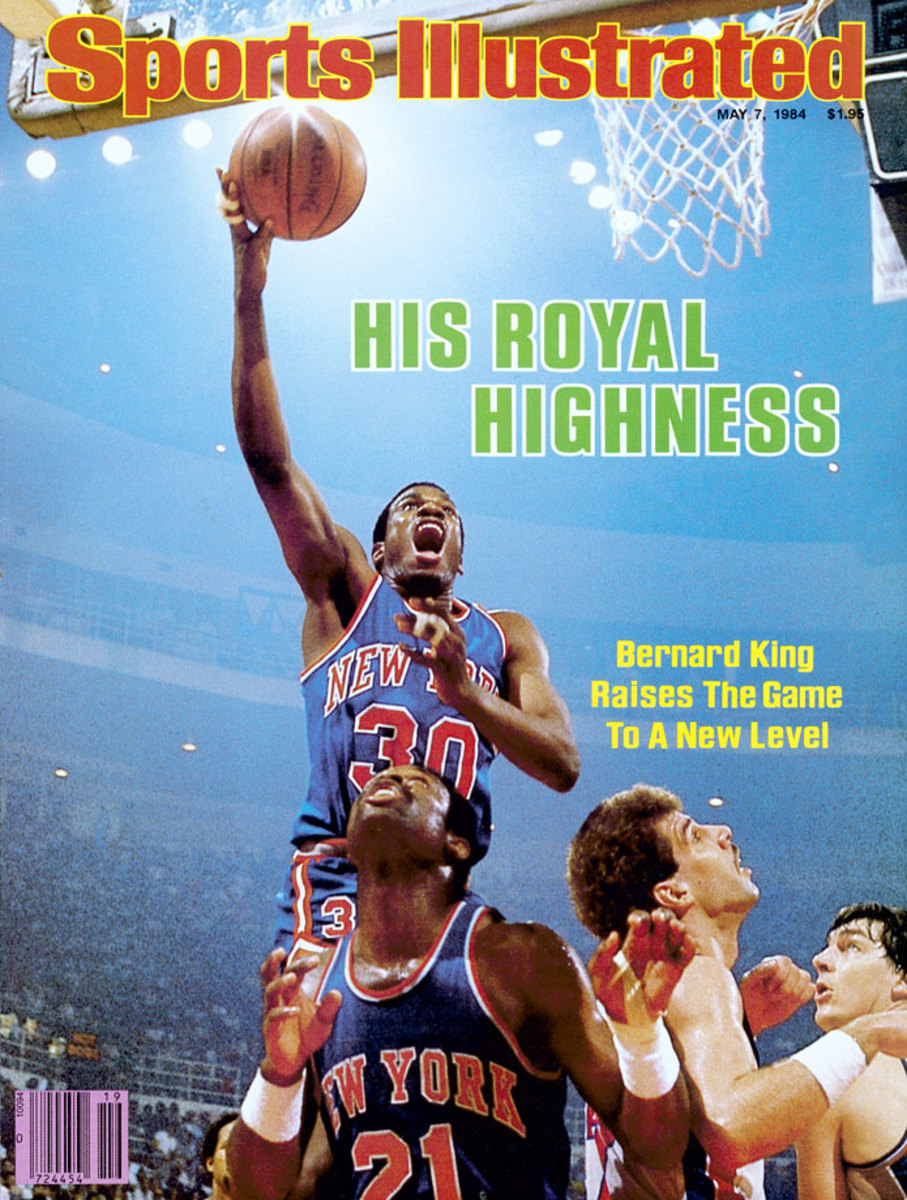

30 — Bernard King

A tremendous athlete and gifted scorer, King came into the league averaging 24.2 points per game as a rookie and went on to become one of the most dominant offensive forwards of the ‘80s. A torn ACL in 1985 sidelined him for more than a year, and he was never quite the same—although he put together a strong comeback at the end of his career, with an impressive 28.4 points at age 34 in his second-to-last season. — Runner-up: Stephen Curry

31 — Reggie Miller

For several years, Reggie Miller was the NBA’s all-time leader in career three-pointers drained. Miller still ranks second, only behind Ray Allen. A five-time All-Star, Miller brought it in the postseason as well, most notably his clutch eight points in nine seconds to beat the New York Knicks in 1995. He led the Pacers to the 2000 NBA Finals as well. — Runner-up: Shawn Marion

32 — Magic Johnson

It’s hard to say enough about Magic, who changed perceptions of what a point guard could be, won multiple titles and became one of the NBA’s most engaging personalities all at once. A five-time NBA champ, three-time MVP, nine-time first-team All-NBA and 12-time All-Star, Johnson, with his playoff hardware and impact on the game, edges out Malone for this spot in a tight one. — Runners-up: Karl Malone, Kevin McHale

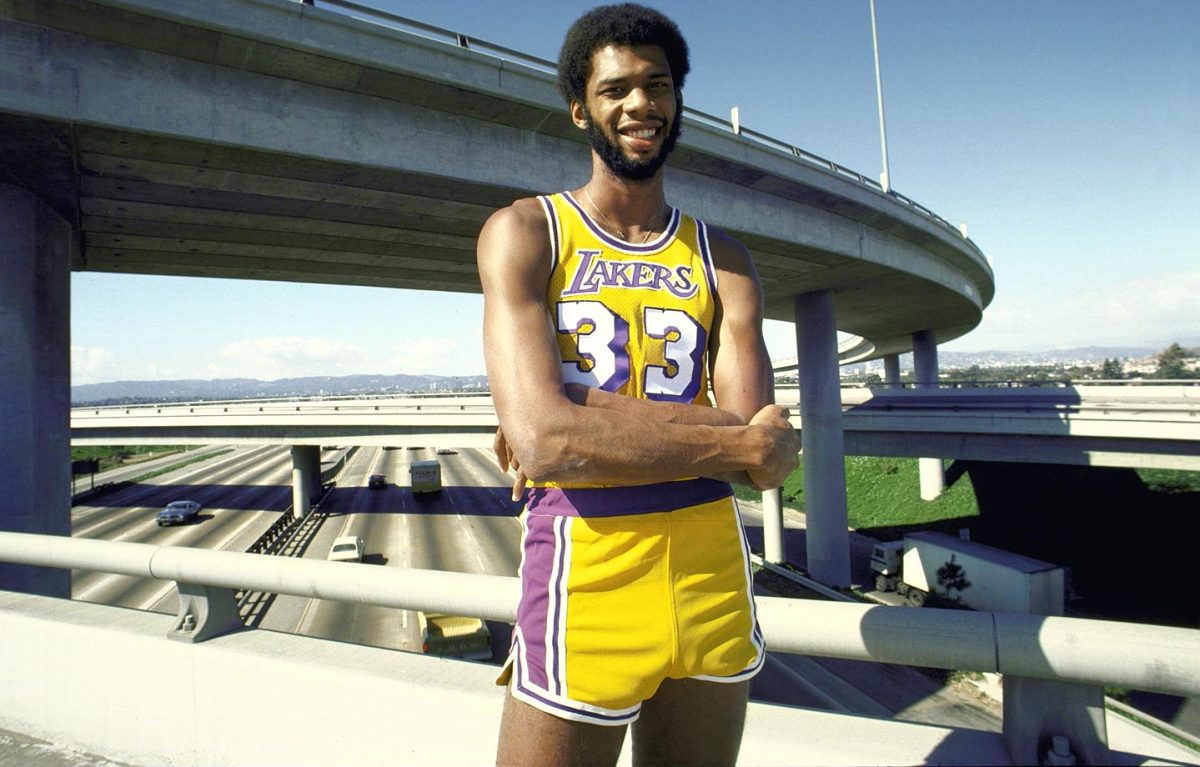

33 — Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Clearly one of the greatest players ever, Abdul-Jabbar is the NBA’s all-time leading scorer by a mile and played in the second-most games of any player in history behind only Robert Parish. Kareem was an All-Star in 19 of his 20 seasons and claimed six championships. His skyhook will, of course, forever be legendary. — Runners-up: Larry Bird, Scottie Pippen

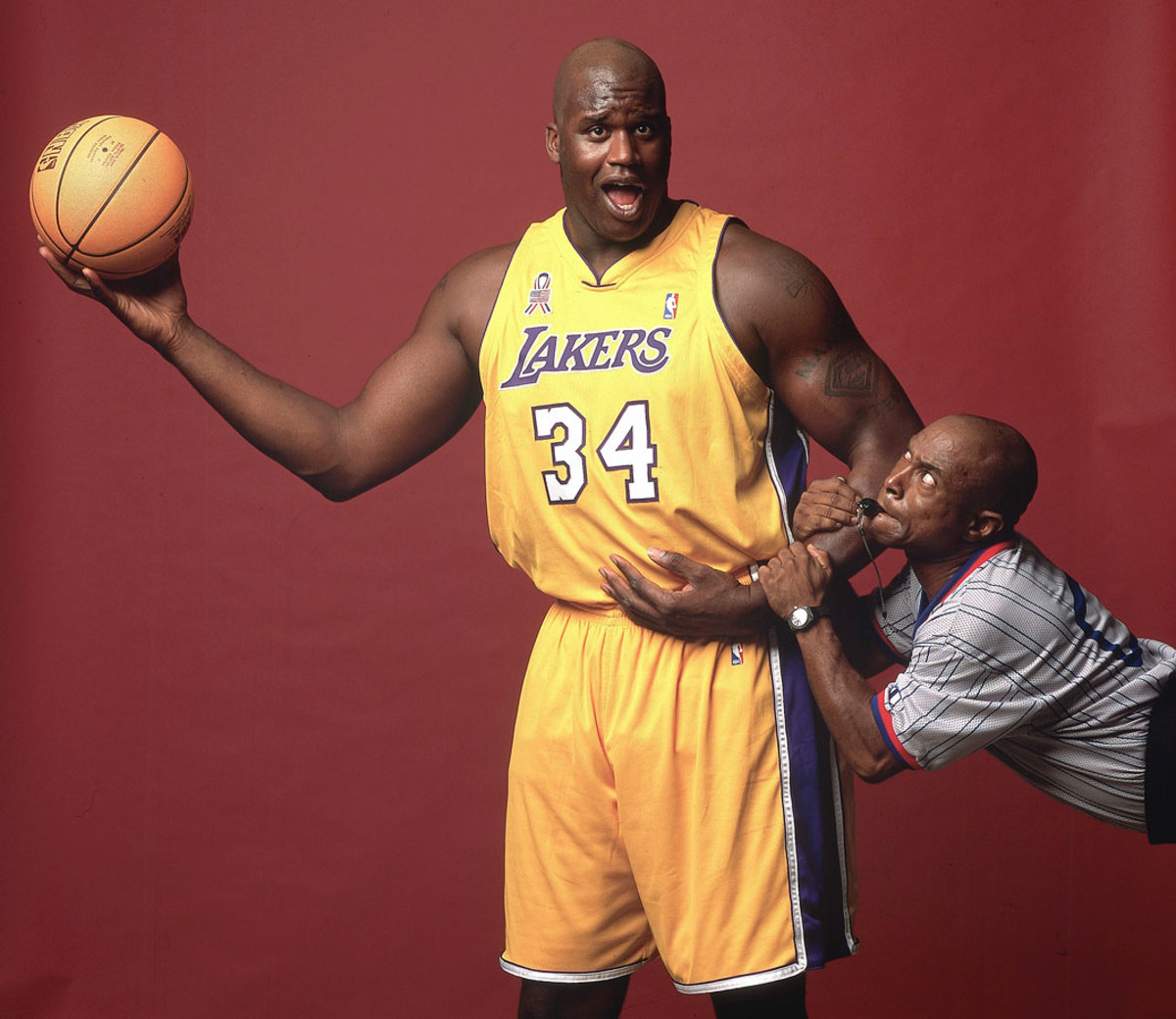

34 — Shaquille O’Neal

Prime Shaq has a case as the most singularly dominant individual player ever, with his blend of power and quickness, soft touch and ability to impose his will on the court. Four titles, three Finals MVPs and 15 All-Star appearances help Shaq’s résumé edge out the competition in one of the more difficult jersey number debates. — Runners-up: Hakeem Olajuwon, Charles Barkley, Ray Allen

35 — Kevin Durant

There’s a reason the entire NBA is holding its collective breath awaiting the 2016 offseason. Durant will be the biggest potential free agent since LeBron James in 2010. He’s a six-time All-Star, a four-time scoring leader and has an MVP to his name. Here’s to hoping he can return seamlessly after three foot surgeries. — Runner-up: Rudy LaRusso

36 — Rasheed Wallace

‘Sheed wore No. 30 for a large portion of his career, too, but he’s by far the most talented to don No. 36 (save for Shaq, briefly — and we aren’t repeating players here). Wallace led Detroit’s ensemble cast to the 2005 title and was a major player in the emergence of the modern stretch-four position. Often controversial, at times transcendent...well, ball don’t lie.

37 — Nick Van Exel

Nick Van Exel never quite found a home in the NBA, but he was far from a journeyman bouncing around from team to team. He played in one All-Star game, having always shown poise running the offense and performing in pick-and-roll sets. He ranks 22nd all-time in career three-pointers made. — Runner-up: Metta World Peace

38 — Viktor Khryapa

Khryapa struggled to find a home in the NBA and was done after four years, but has been a top player back in his native Russia before and after his American stint. He averaged 5.8 points and 4.4 rebounds for Portland in his best season.

39 — Jerami Grant

In just one NBA season, Grant posted the best statistical year of any player to don a No. 39 jersey. Grant settled on No. 39 after the Sixers made him the 39th pick in the 2014 NBA draft. He showed tremendous strides in his first season, draining 31.4% of his three-pointers on 156 attempts after hoisting just 20 triples in his two years at Syracuse. — Runner-up: Greg Ostertag

40 — Shawn Kemp

Kemp quickly became one of the NBA’s most exciting players and finished a six-time All-Star, his one-two punch with Gary Payton remaining one of the league’s more iconic pairings. At his best, he was a double-double machine and effective shot-blocker, threat to dunk on his defender and anchor for the Sonics on the way to the ‘96 NBA Finals, where they’d fall to Jordan, Pippen and the Bulls. —Runner-up: Bill Laimbeer

41 — Dirk Nowitzki

Arguably the greatest shooting big man of all-time, Nowitzki cemented his legacy after leading the Mavericks to a come-from-behind championship against the Heat in 2011. Nowitzki claimed the 2006 regular season MVP and has appeared in 13 All-Star Games. — Runners-up: Wes Unseld, Glen Rice

42 — James Worthy

Worthy spent much of his career as the third banana on the Lakers alongside Kareem and Magic, but became an all-time great one in the process, getting his numbers and playing a critical role throughout. He averaged 17.6 points on 52.1% shooting in his 12 years as a Laker and came away a three-time NBA champion and seven-time All-Star. — Runners-up: Elton Brand, Kevin Love, Connie Hawkins

43 — Jack Sikma

At just 23 years old, Sikma helped the Seattle Supersonics claim their only championship in franchise history, averaging 14.8 points and 11.7 rebounds per game in the 1979 postseason. A seven-time All-Star, Sikma ranks 30th all-time in NBA history in career total rebounds. — Runner-up: Brad Daugherty

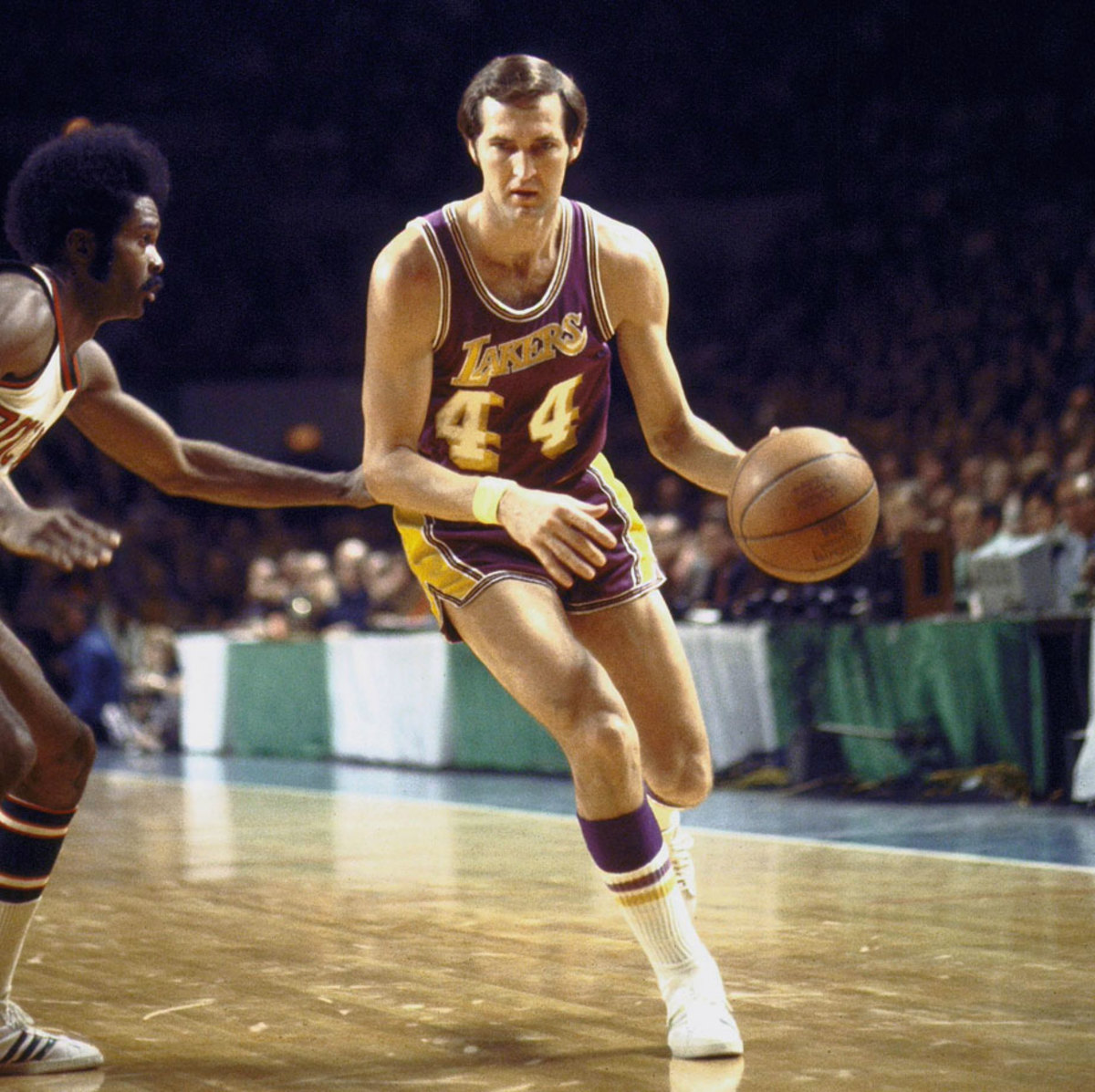

44 — Jerry West

He’s on the NBA logo and forever etched into its history as a player and executive. Jerry West was a 14-time All-Star and 1972 NBA champion, and lost in the historic romanticism and his efforts in the Lakers’ front office is the fact that he straight up put the ball in the basket. With an average of 27 points per game over 14 seasons, all before the advent of the three point line, West’s transcendence as a player is tough to argue against. — Runner-up: George Gervin

45 — Rudy Tomjanovic

The No. 2 overall pick in the 1970 NBA draft, Rudy Tomjanovic is the third leading scorer in Rockets franchise history behind only Calvin Murphy and Hakeem Olajuwon. A five-time All-Star, Tomjanovic’s last name was so long, the back of his jersey often read, “Rudy T.” — Runner-up: A.C. Green

46 — Bo Outlaw

A terrific athlete, tough defender and abysmal free-throw shooter, Outlaw carved out a long career for himself despite an uninspiring statistical profile. His game peaked in 1998, with 25 points, 13 rebounds and 10 assists in a win as a member of the Magic. A reporter asked him how he felt about his triple-double, which led to Outlaw’s famous reply: “What’s that? Some kind of hamburger?”

47 — Andrei Kirilenko

In 2001, Kirilenko joined the Jazz after Utah made him the first Russian player drafted in NBA history in 1999. Kirilenko was named an All-Star in 2004 and was a three-time first-team All-Defense selection. Kirilenko was instrumental in Utah’s transition from John Stockton and Karl Malone to the Deron Williams and Carlos Boozer era. — Runner-up: Scott Williams

48 — Nazr Mohammed

A career journeyman, Mohammed had serviceable years earlier in his career before seeing his playing time dwindle with age in Oklahoma City and now Chicago. He won a title in 2005 as a backup with the Spurs but peaked statistically as a Hawk in 2001-02, with 9.1 points and 7.9 boards per game.

49 — Shandon Anderson

Anderson far exceeded expectations throughout his career after being drafted with the 54th pick in the 1996 NBA draft. In his 10-year career, Anderson’s best season came in 1999-2000, when he averaged 12.3 points, 4.7 rebounds and 2.9 assists per game for the Rockets. He was a reserve on the Heat’s 2006 championship team. — Runner-up: Mel McCants

50 — David Robinson

The Admiral was an incredible talent whose individual greatness occasionally gets lost because of the team-first nature of the Spurs’ dynasty and Tim Duncan’s sustained quality. Robinson was part of the Spurs’ first two championships (1999 and 2003), teaming with Tim Duncan to lay the groundwork for what was to come. But a young Robinson could carry a team, make no mistake about it: he averaged 29.8 points and 10.7 rebounds in 1994 and averaged 21.1 points for his career. — Runners-up: Steve Mix, Ralph Sampson, Zach Randolph

51 — Reggie King

The 18th overall pick in the 1979 NBA draft, King played four seasons for Kansas City before finishing his career for two years in Seattle. During his second year with the Kings, in 1980-81, King posted his best season, averaging 14.9 points and 9.7 rebounds and shot 54.% from the field. — Runner-up: Lawrence Funderburke

52 — Jamaal Wilkes

Overshadowed by star teammates but statistically impressive, Wilkes was a key player in the Lakers’ incredible run of success. He won Rookie of the Year as part of Golden State’s title team in 176, captured three titles with the “Showtime” Lakers and averaged 17.7 points and 6.2 rebounds for his career. There may not be a better metaphor for his career than this: he scored 37 points and 10 rebounds in 1980’s Game 6 to clinch the Finals, which happened to be the same game Magic famously started for Kareem at center and finished with 42 points, 15 rebounds and seven assists.

53 — Artis Gilmore

Still the NCAA’s all-time leader in rebounds per game, Gilmore made five All-Star appearances in the ABA. The Chicago Bulls made Gilmore the No. 1 overall pick in the 1976 dispersal draft as part of the NBA-ABA merger. Gilmore appeared in six NBA All-Star games. He is still the NBA’s career leader in field goal percentage at 59.9%. — Runner-up: Darryl Dawkins

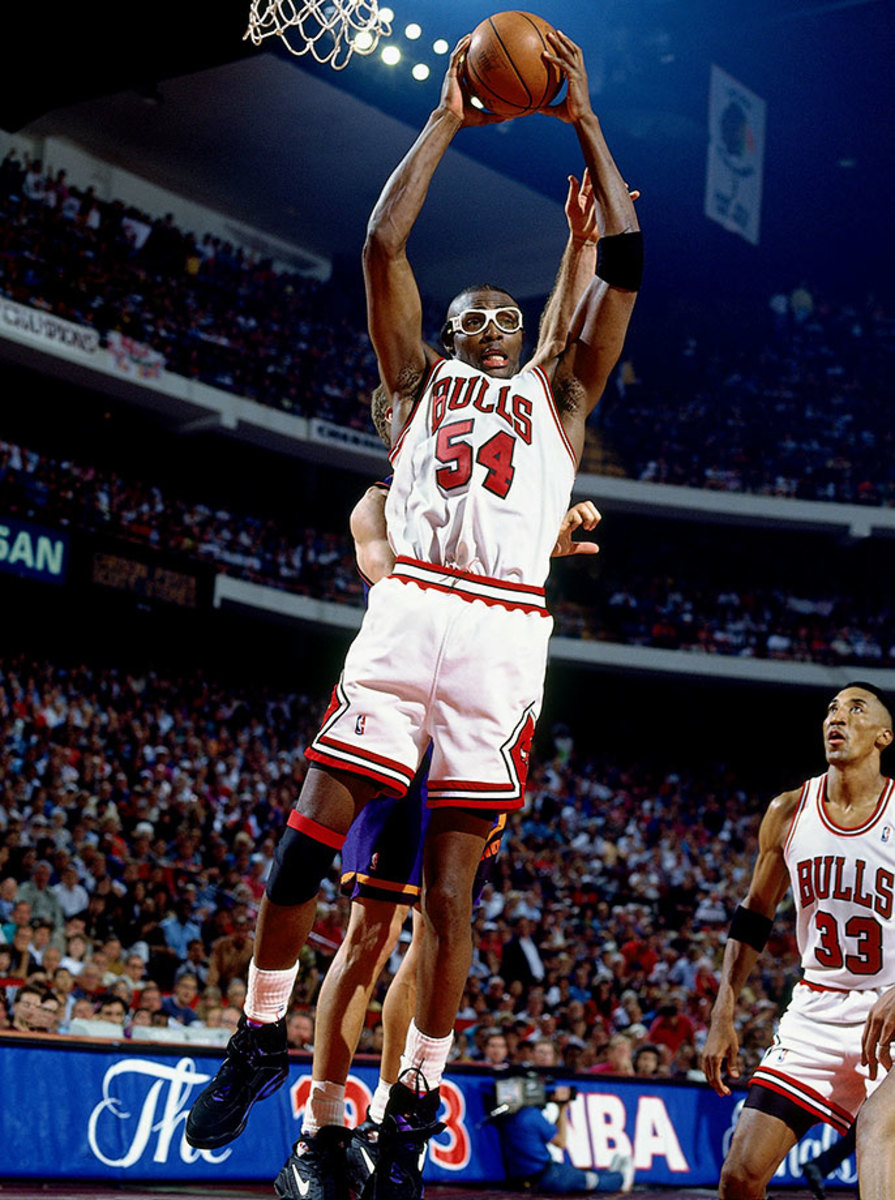

54 — Horace Grant

The Bulls drafted Grant five picks after Scottie Pippen in 1987, two moves that would greatly add to the cast around Michael Jordan and lead to Chicago’s first three-peat. Grant left the Bulls after an All-Star season in 1994. He never quite hit that peak again, but Grant was an effective two-way player and would earn another ring with the Lakers in 2001.

55 — Dikembe Mutombo

His full name, Dikembe Mutombo Mpolondo Mukamba Jean-Jacques Wamutombo, is almost as long as his stellar 18-year career. Mutombo ranks second all-time in NBA history in career blocks, was an eight-time All-Star and earned Defensive Player of the Year honors four times. He reached the playoffs in 13 seasons. — Runner-up: Kiki Vandeweghe

56 — Francisco Elson

Hailing from the Netherlands, Elson was a second-round pick who would never make a major impact at the NBA level. He did start 54 games for Denver in 2006 and gain some fame for scuffling with Kevin Garnett in the playoffs that year. He won a title with San Antonio in 2007, starting 41 games that season.

57 — Hilton Armstrong

The UConn product and 12th overall pick in the 2006 NBA draft, Armstrong is the only player in NBA history to have worn #57. Armstrong donned the number in the 2013-14 season, in which he appeared in 15 games for the Golden State Warriors. Armstrong’s best year came in 2008-09, when he averaged 4.8 points and 2.8 rebounds for the New Orleans Hornets.

61 — Bevo Nordmann

After the Cincinnati Royals selected him with the second pick in the third round of the 1961 NBA draft, Nordmann played just four seasons in the NBA. He wore No. 61 in his rookie season in 1961-62. Nordmann averaged 7 points and 6 rebounds for the St. Louis Hawks and New York Knicks (pictured here wearing No. 22) in the 1962-63 season. — Runner-up: Dave Piontek

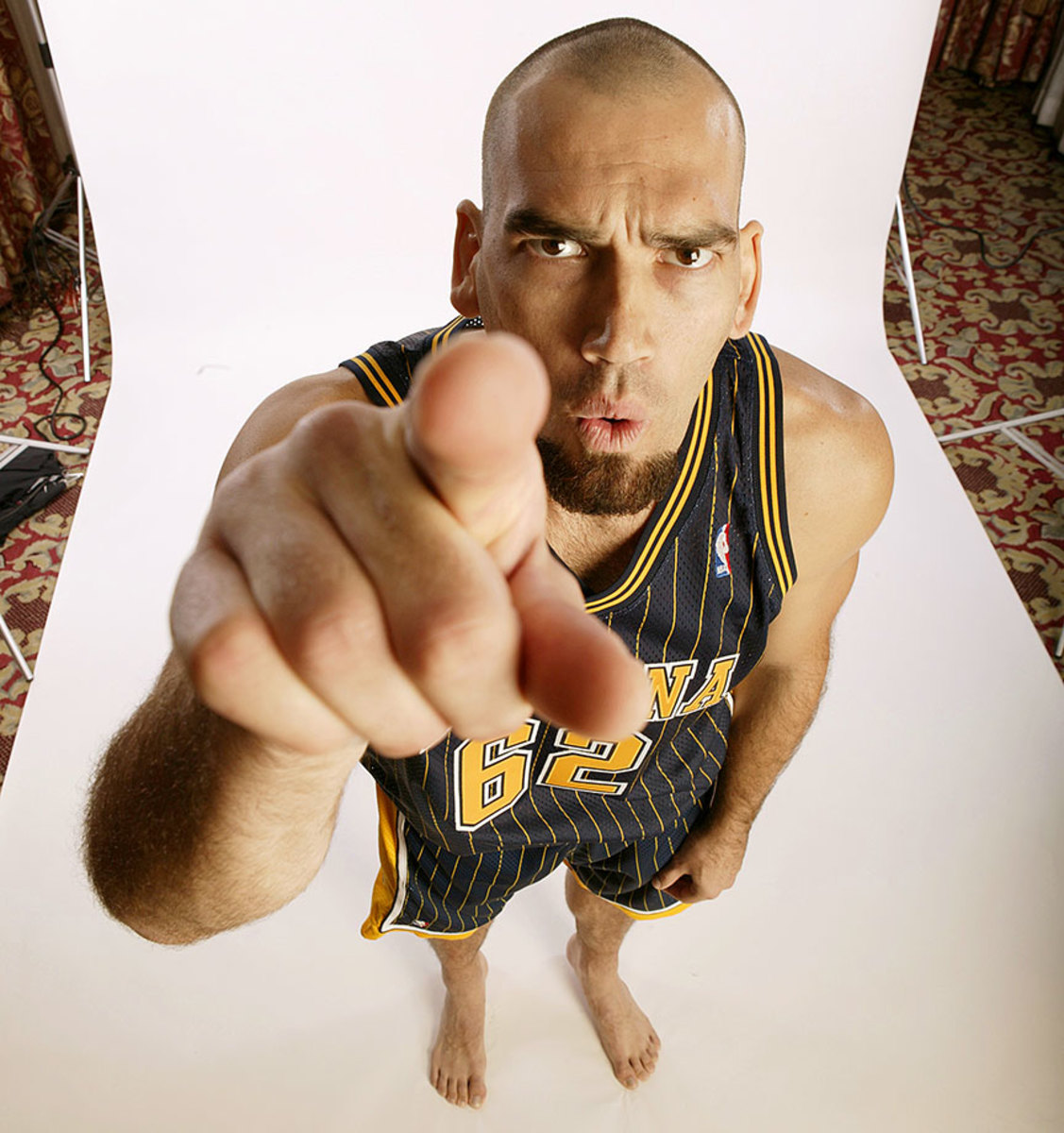

62 — Scot Pollard

Pollard was notorious for his tough defensive play and variety of wild hairstyles, and not necessarily in that order. Still, he appeared in the playoffs in nine of his 11 seasons and made his greatest impact backing up Vlade Divac with the Kings in the early 2000s, occasionally filling in at power forward when Chris Webber was hurt.

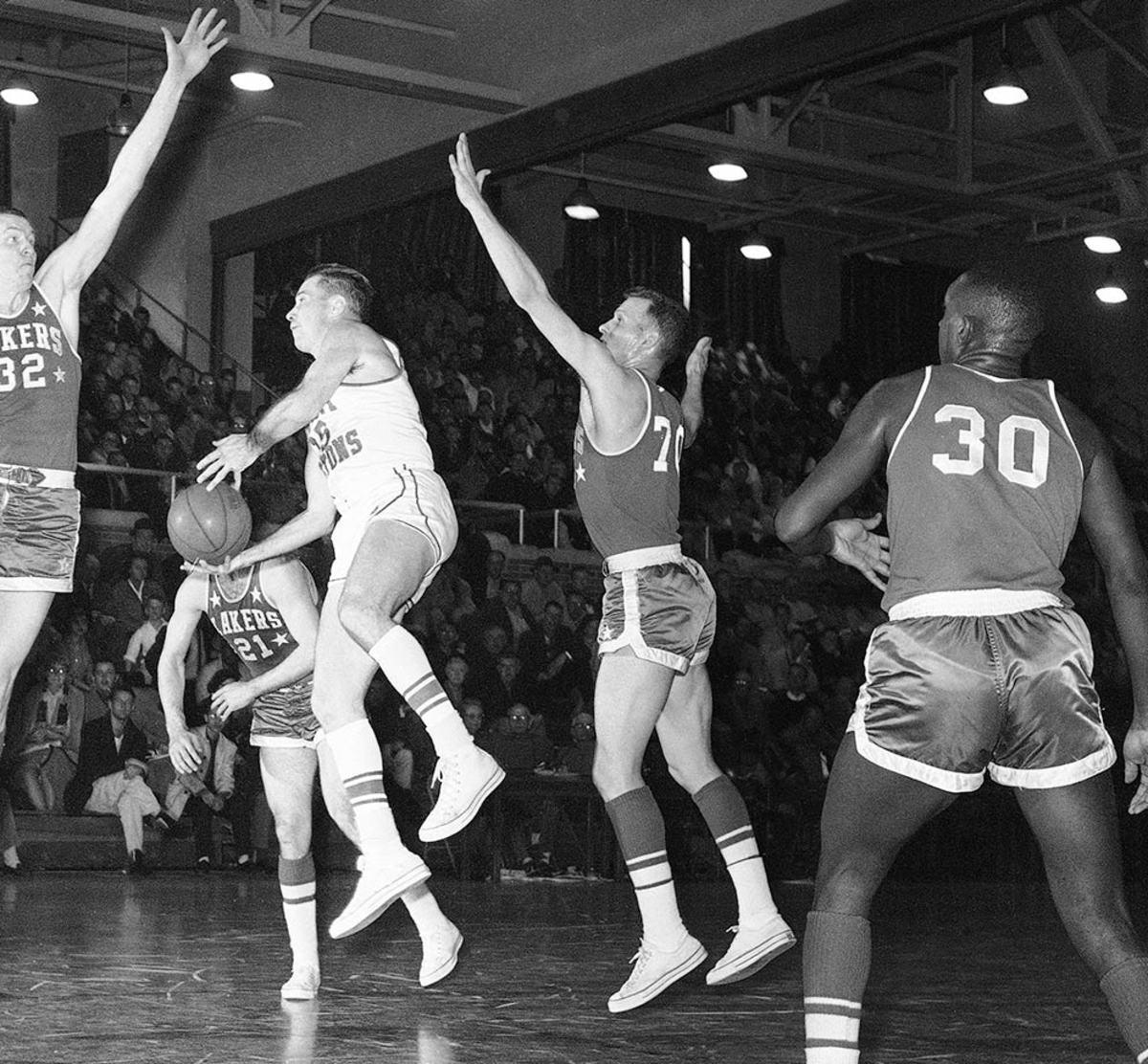

70 — Frank Selvy

Selvy holds the NCAA Division I record for points in a game with 100 (yes, you read that right). He was the first overall pick in the 1954 NBA draft and averaged 10.8 points per game in ten seasons. Selvy was a two-time NBA All-Star and a teammate to Elgin Baylor and Jerry West with the Lakers.

71 — Willie Naulls

A four-time All-Star, Willie Naulls starred for the New York Knicks during the late 1950s and early 1960s. From 1959 to 1962, Naulls averaged over 20 points and 10 rebounds before game. He wore No. 71 for the Golden State Warriors for 47 games in the 1962-93 season after the Knicks traded him for Tom Gola. — Runners-up: McCoy McLemore, Bob Wiesenhahn

72 — Jason Kapono

Kapono was the second-to-last pick of the 2003 NBA draft and had a relatively nice nine-year career as a role player known for his shooting ability. He led the league in three-point percentage with a 51.4% clip in 2006-07 as a member of the Heat, the year following Miami’s title win. He also outshot Dirk Nowitzki and Gilbert Arenas to win the shootout at All-Star weekend that year and would successfully defend that title in ‘08.. Kapono holds the distinction of blocking the first shot in Bobcats history as a member of Charlotte’s expansion roster.

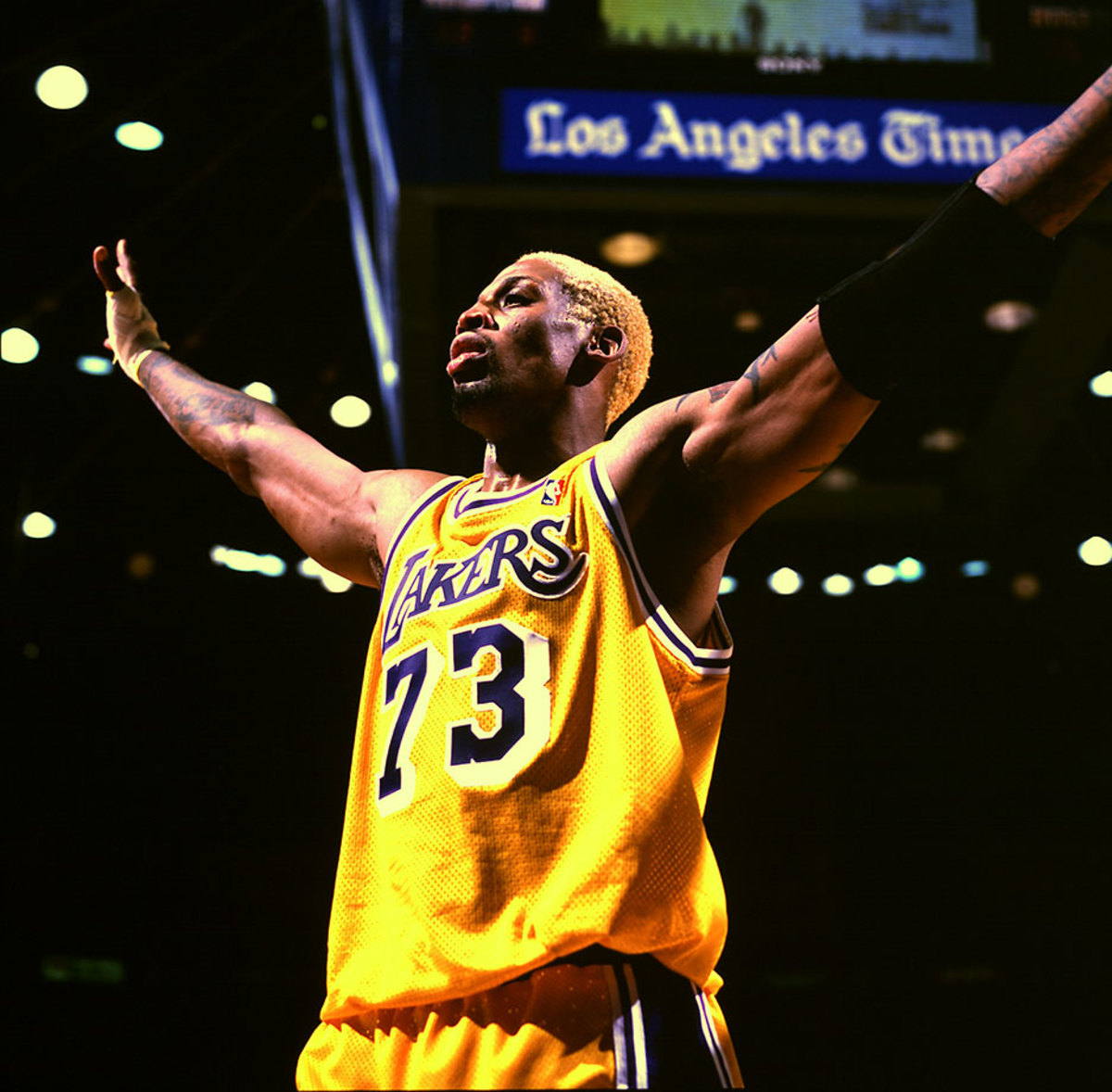

73 — Dennis Rodman

Rodman’s most famous for wearing No. 91, and is the only player to make this list twice, given he became the only player in NBA history to wear No. 73 when he suited up for the Los Angeles Lakers in the 1998-99 season. He’s a five-time NBA champion, winning two as a “Bad Boy” Piston and three with Jordan’s Bulls, and set an NBA record by leading the league in rebounding for seven straight seasons (1991-98).

76 — Shawn Bradley

Standing 7’6”, Bradley’s height made him an NBA commodity and he enjoyed a solid career functioning primarily as one of the league’s best shot-blockers. He averaged three or more blocks per game in each of his first six seasons while also rebounding effectively and scoring when needed. Bradley also took a memorable turn as a supporting character in Space Jam.

77 — Gheorghe Muresan

At 7’7”, Muresan is the tallest player in the NBA history, along with the late, great Manute Bol. Muresan earned the 1995-96 Most Improved Player award after averaging 14.5 points, 9.6 rebounds, 2.2 blocks per game while making a league-leading 58.4% of his field goals. — Runners-up: Vladimir Radmanovic, Jake Voskuhl

83 — Craig Smith

The 36th overall pick in the 2006 NBA draft, Smith is the only player to wear No. 83 in league history. Smith wore the number when he appeared in 47 games for Portland in the 2011-12 season. His best season came in 2008-09, when he averaged 10.1 points and 3.8 rebounds per game for Minnesota.

84 — Chris Webber

C-Webb only donned No. 84 after his prime, in his lone part of a season with Detroit after being traded in 2007. But Chris Webber was a dominant force before a serious knee injury in the 2003 playoffs, one of the NBA’s best post passers and dynamic power forwards. He was a five-time All-Star, averaging 20.7 points and 9.8 rebounds in 15 seasons. But the hopes of the entertaining Kings teams of the early 2000s went down when Webber did, and he would retire without a title to his name.

85 — Baron Davis

After the Hornets selected him third overall in the 1999 NBA draft, Davis became a two-time All-Star. He most notably led the eight-seeded Warriors to a 4-2 first round upset of the top-seeded Mavericks. He’s the only player in NBA history to wear No. 85, doing so for both the Cavaliers and Knicks.

86 — Semih Erden

Erden, a 7-foot Turkish center, played three NBA seasons and played in just 69 games. He started nine games for the Cavaliers in 2011-12 and headed back overseas the next season, playing in his native country ever since. — Runner-up: Chris Johnson

88 — Nicolas Batum

Batum, a late first-round pick, was traded to Portland from Houston for the rights to Darrell Arthur and Joey Dorsey on draft day 2008. His career’s been solid, with a well-rounded game and good size and ball skills. But 2012-13 was a highlight year for Batum, when he averaged 14.3 points, 5.6 rebounds and 4.9 assists. The Frenchman was traded to Charlotte in the off-season and will start fresh as a Hornet this fall. — Runner-up: Antoine Walker

89 — Clyde Lovellette

The ninth overall pick in the 1952 NBA draft, Lovellette wore No. 89 in his rookie season for the Minneapolis Lakers. A four-time All-Star, Lovellette averaged 17 points and 9.5 rebounds per game during his 11-year career. Lovellette was part of three NBA championship teams. — Runner-up: Louis Amundson

90 — Drew Gooden

A number of NBA stops haven’t kept Gooden from posting decent production, though he has not quite justified his fourth overall selection in 2001. He came into a role with the Wizards last season and averaged double figures in scoring every season up until 2012.

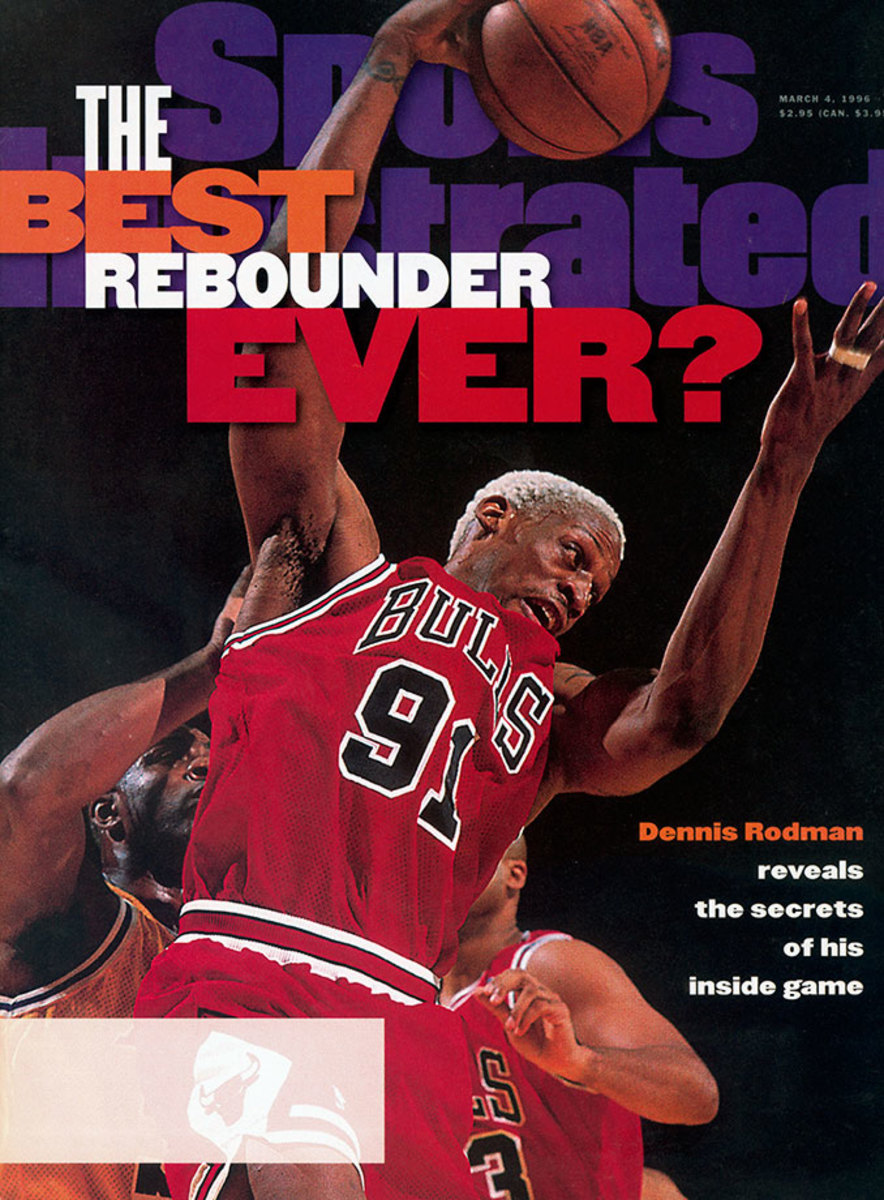

91 — Dennis Rodman

Rodman, appearing for the second time on this list, retired with a reputation as one of the NBA’s greatest rebounders ever, not to mention a strong defender and enormous off-court presence with a penchant for dying his hair on the regular. He won five titles, was Defensive Player of the Year twice, made seven All-Defensive first teams and two All-Star teams, and became one of America’s most polarizing athletes in the process.

92 — DeShawn Stevenson

Stevenson never came close to his prep-star hype, but bounced around supplying average production much of his career. He had a moment for the Mavericks during their 2011 title run, famously proclaiming himself the “LeBron stopper.” And hey, Dallas topped Miami. For all we know, he still holds that title.

93 — Metta World Peace (Ron Artest)

Before changing his name to Metta World Peace, Ron Artest wore No. 93 from 2006-08 with the Sacramento Kings. Artest donned seven different numbers in his career, and his personality and antics both on and off the court have overshadowed just how good he was in his prime. An elite, versatile defender for many years, Artest was averaging 24.6 points per game in 2005 before being suspended for the “Malice at the Palace” incident and missing the entire season.

94 — Evan Fournier

The French guard took a step forward last year at age 22, averaging 12 points per game for the Magic. He’s become a member of the French national team as well. The best may still be to come.

96 — Metta World Peace (Ron Artest)

Not surpisingly, a player who donned seven different numbers in his career would appear twice on this list. Metta World Peace, then Ron Artest, wore No. 96 in the 2008-09 season with the Houston Rockets. He led the team in three-pointers and steals, finishing second in scoring behind Yao Ming. He won a title with the Los Angeles Lakers the following season.

98 — Jason Collins

Collins never lived up to his first-round selection, but carved out a niche as a defensive-minded reserve center and hung around for 13 seasons. He averaged 3.6 points and 3.7 rebounds for his career. Collins became the first openly gay NBA player in 2014 and chose number 98 to honor Matthew Shepard, who was murdered in a 1998 hate crime.

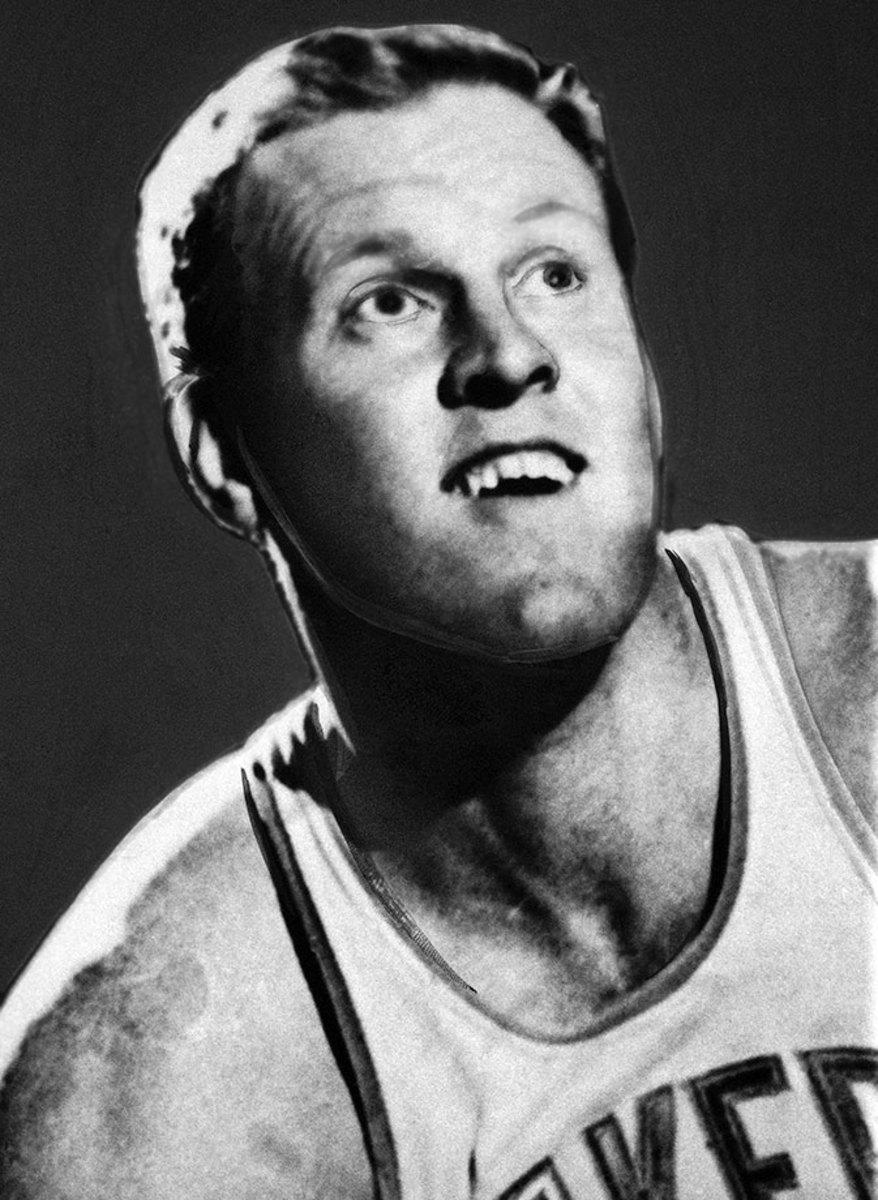

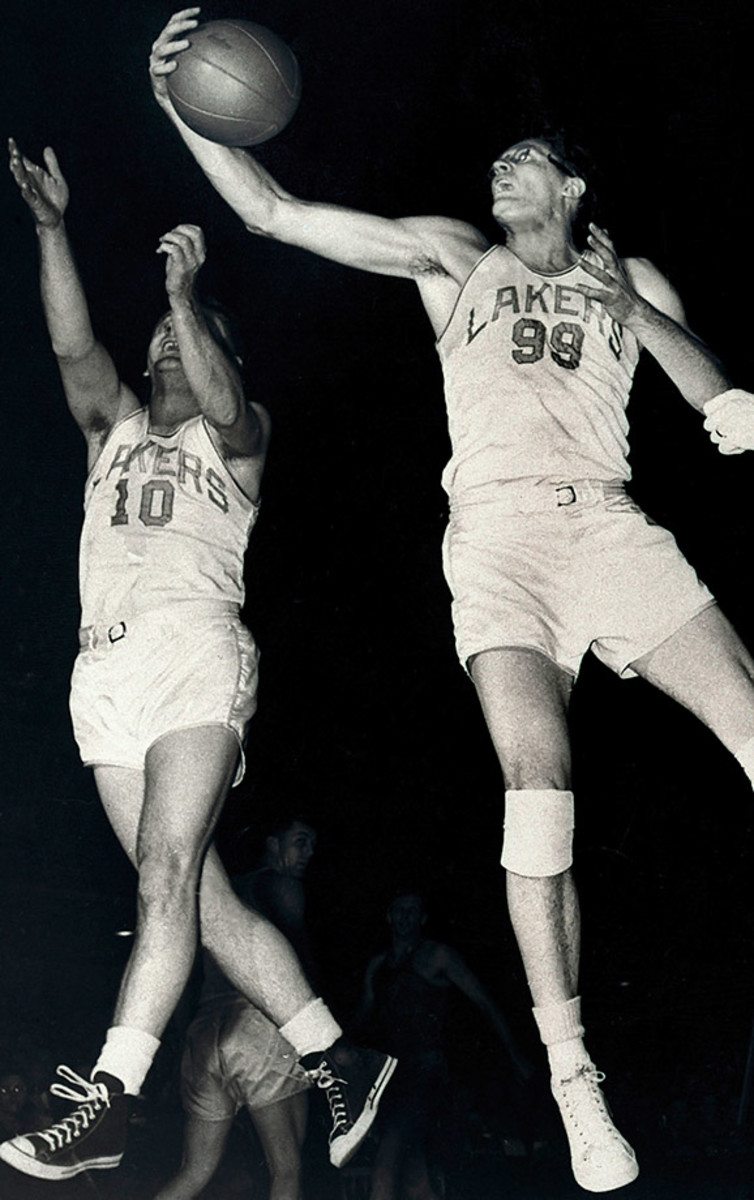

99 — George Mikan

One of the game’s original superstars, Mikan was quite literally a giant among men at 6’10” in the 1940s and 1950s. He led the Lakers to four NBA championships and one BAA title before becoming an NBA franchise. Mikan was a four-time All-Star and was named one of the 50 greatest players in NBA history in 1996.

That has not stopped coaches on other teams from being intrigued at the thought of coaching Dawkins at some point in his career. Nelson says there was a period of four or five years when probably every NBA coach "felt he could be the guy to really reach him, the guy who could tap into his potential and make him a perennial All-Star. But those expectations are gone now."

Not quite, but they are fainter. Pistons coach Chuck Daly believes Dawkins may play again—not necessarily with Detroit. A few other coaches say they have not written off the possibility of obtaining Dawkins—if he is in shape, if he wants to play, if his head is on straight. If, if, if, if.

Go back to last November: Dawkins weighs close to 300 pounds but is telling anyone who will listen that this season he is going to be like "Agent 0014—twice as bad as 007!"

He has not played much for almost two years. In that time he has had back surgery twice and his wife of one year has committed suicide. His father has been diagnosed as having stomach cancer. There are rumors of financial trouble. He rarely answers his phone or his doorbell. There are no more names for his dunks, because there have been no more dunks. He was traded twice within two months, first on Oct. 8 to Utah and then on Thanksgiving Day from Utah to Detroit, where after only two games he was placed at his own request on the suspended list because of his personal problems.

He wishes he could stop en route to Lovetron, his imaginary planet, and sort out all of these puzzling and upsetting developments. He has not heard the word potential for almost two years.

Dawkins and I are sitting in a Mexican restaurant in the North Jersey suburbs. He is eating a tortilla after having unscrewed the top of the pepper shaker and poured half its contents onto his food. I laugh when I see him do it because it reminds me of the first time I ate with him after becoming the coach of the Nets. He had produced his own bottle of Tabasco sauce that day to add a little spice to the meal.

He says the events of the past three seasons—the operations, the death of his wife, the trades—are finally fading from his thoughts. He has started to work out. He wants to play again. "If not here, maybe in Europe." He's not concerned about finding a new team. "Someone always needs a big body," he says.

Would he change anything if he could do it all over again? Dawkins doesn't even pause to reflect on the question. He has answered it to himself many times. "No," he says, shaking his head. "I wouldn't change a damn thing. I always liked being Darryl Dawkins."

I'm tempted to say that this is tragic. I think of the words of the philosopher Santayana, who once said, "Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it."

Yet I realize that I am still subjecting Dawkins to the parameters of my own standards. I want him to live up to my expectations regardless of his own hopes. Perhaps I am the one who has not learned from the past. After all, whose expectations should we live up to? Our own or everyone else's?

Dawkins is 31 and believes he can play four or five more years. He says he has nothing to prove to anyone. And don't expect him to change Just because he plays in a new location. He will play as he always has, smiling and joking and conserving energy as the veterans told him to a long time ago.

Though he has never reached his potential, he has, curiously, outlasted it. He has evolved from the next coming of Chamberlain into simply another big body that somebody, somewhere, will need. He has wrestled with the monster called Potential, and he has won because he has not let it destroy him.

Most of us will judge him solely on what he could have been in the beginning or what he was when his career ended. Too many will be blinded by the flashes of brilliance that never materialized into consistent greatness. They will overlook much of Dawkins's career. No, it was not great. But it was solid. Perhaps he could have been more if he had had the inclination. There were times when he teased us with a hint of how he could dominate a game. And we went home in awe and yet sad because we knew of no spell to make it happen more frequently. But few players could make us feel that way even once.

Darryl Dawkins is content with his career and with himself. He has endured the burdens heaped on him when he was 18 years old. He has carried the weight of others' dreams and desires and expectations and is still able to get up in the morning and smile at the reflection in the mirror.

We should all be so lucky.