The Man Who Helped Make Pop... And Me

The list was taped to the wall in a dark corner of an old college gymnasium, the kind with a running track overhanging the corners of the playing surface. The wall was made of ancient, yellowed stones, lacquered for preservation; the paper was a single, unlined white sheet, affixed to the bricks with slices of clear tape. Even nearing midday, there was barely enough light to read the printing on the page, listing the names of those who had earned the right to play on the varsity basketball team at Williams College during the upcoming season.

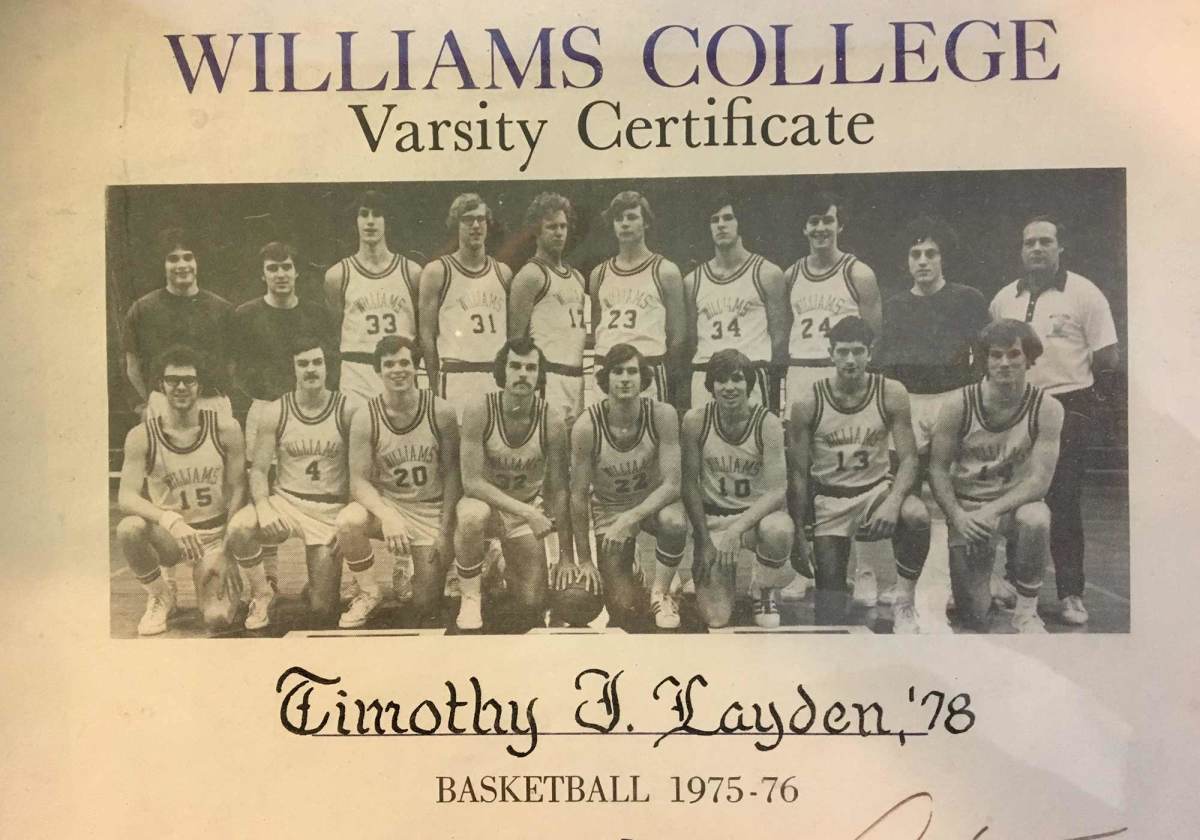

It was late in the fall of 1976. I was a junior at Williams, a small D-III liberal arts school in Massachusetts, and had been a member of the team the previous year. I had played little in games, and never when the outcome was in doubt. I was slow-footed, with a tenuous handle, but I could score if not guarded too closely and I was a good teammate and a hard worker. Without being told so, I was certain that my position on the roster was safe until graduation. This was a miscalculation. On the previous night there had been an intrasquad scrimmage, ostensibly giving players a last opportunity to prove themselves worthy of inclusion, or to cut themselves by exposing their weaknesses. Time has dulled the memory of that night, but I didn’t convince my coach that I was significantly better than the bench player I had been the year before. And in retrospect, I most certainly was not.

Therefore, the next day my name wasn’t on the list. I stood frozen at the wall for a long time, repeatedly scanning up and down, trying to blink back the tears that were stinging my eyes and making me feel ashamed. A few of the guys silently patted me on the shoulder, but I waited for all of them to leave before turning to face the daylight. I was 20 years old and my entire self-worth was wrapped up in being an athlete. Now that was gone. I would never again wear a uniform with a genuine name on the front ("Freight Heads," my trucking company-sponsored team in an Albany, New York rec league, is not a genuine name). I was adrift. There is nothing in sports quite like being cut, and nothing quite like the cut that tells an athlete that he has officially bumped up against his own personal ceiling. This is as true of the little boy (or girl) who doesn’t make the high school freshman team as it is of Jimmer Fredette in the NBA. You never forget that cut, even as life piles on more important crises, failures and tragedies, as life will inevitably do, and has. Three decades after I was cut, my daughter enrolled at Williams and we walked through the gym, which was no longer used for varsity games. The wall was still there, the bricks were still a pale, shiny yellow. There was no list, but I could see it just the same. I had to take a minute to gather myself. Again. There is a scene in the movie Miracle, where Kurt Russell, as Herb Brooks, makes Ralph Cox the last cut from the 1980 Olympic hockey team. Kills me.

On that morning in 1976, as players looked at the list on the wall, my coach sat on the windowsill across the gym floor. His office was only a few feet away, but he sat out in the open where anyone with a gripe could visit without being forced to rap his knuckles on the door. That was a professional touch and it couldn’t have been pleasant. The coach’s name was Curtis Whitfield Tong. Curt. Coach Tong. He was 42 years old and had been, at that point, a college basketball coach for 12 years—nine at Otterbein College in Ohio and three at Williams. I walked across the gym and sat next to him. My father had long drilled it into my head to always be a gentleman, and to always take defeat with class, so I told Coach Tong that I understood why he cut me (which was true, but in my immature youth, I didn’t resent him any less for doing it). Coach Tong thanked me for my hard work, told me I was a good player, just not quite good enough. Promised me there would be better days ahead. We shook hands. I walked out of the gym, cried for a few hours and then got drunk for a week.

The purpose of all this musty storytelling, from a very mediocre player, long grown old?

Coach Tong died on January 16 at a nursing home in Massachusetts. He was 82 years old and succumbed to complications of Alzheimer’s disease, which had afflicted him in the latter years of a very rich and full life. He left behind his wife of 58 years, the former Wavalene Kumler, whom everyone knows as Jinx. They met in college and stayed together, a love story. They had three children, accomplished and successful adults who had seven children of their own, and last spring, Curt's and Jinx’s first great-grandchild, a little girl named Martha. They are a close and beautiful family. Curt coached 18 years at Otterbein and Williams, with a combined record of 242 wins and 141 losses. In 1983, at the age of 49, Curt left Williams to become the athletic director at Pomona-Pitzer, two small California liberal arts colleges that share an athletic department. He spent the last 16 years of his career there, before retiring in 1998. In 2010, he published a memoir, Child Of War, describing in harrowing detail the three years he spent as a child in a World War II Japanese internment camp in the Philippines, where his parents were missionaries.

Those are the details, and they are important details. They are a life’s work, in and out of the office. On and off the court. But details never tell the full story of a coach’s life, because a coach—a teacher, by any measure—is more than the sum of his life’s accomplishments. A coach is his own life, and every life he has ever touched, his words and his lessons melting down through generations, outliving him by decades. Coaches expire every day, but they never die. They live forever. When I talked to Coach Tong on that windowsill in 1976, I knew nothing of the man and nothing of his life—or life, period. I knew only that he had taken away my spot and my identity and I was angry at him for that. (Anyone who has ever been cut from a team reviles the coach who dropped the axe, whether for a moment or for a lifetime. The coach knows this best of all). Over the years he would teach me much more. And he would teach many others, too.

One of them was Gregg Popovich.

When Curt Tong arrived at Pomona-Pitzer in the fall of 1983, he inherited a 34-year-old, fifth-year head basketball coach. Popovich has become one of the most respected coaches in the history of the sport, not only for his five NBA titles, but also for his creativity, stubbornness and, most recently, willingness to put voice to his social conscience. The game’s history will someday write his name on a very short list. But at Pomona-Pitzer he was just a relative novice trying to cobble together victories at a college that was awash in brilliant students, but hadn’t cared about winning or losing in sports for a very long time. His first team had gone 2–22 and lost to Cal Tech, ending that school’s 99–game losing streak. (For a good read on Popovich’s time at Pomona-Pitzer, I recommend this from 2015, by Jordan Ritter Conn for Grantland).

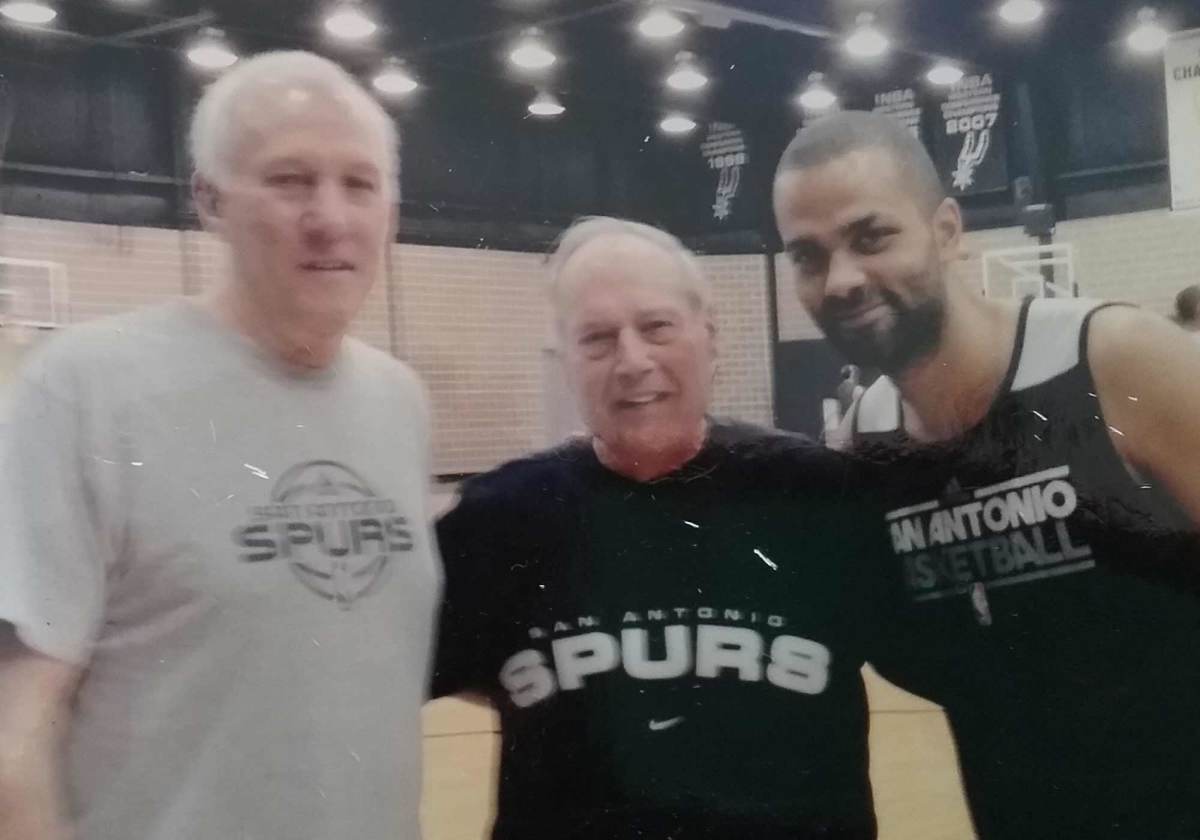

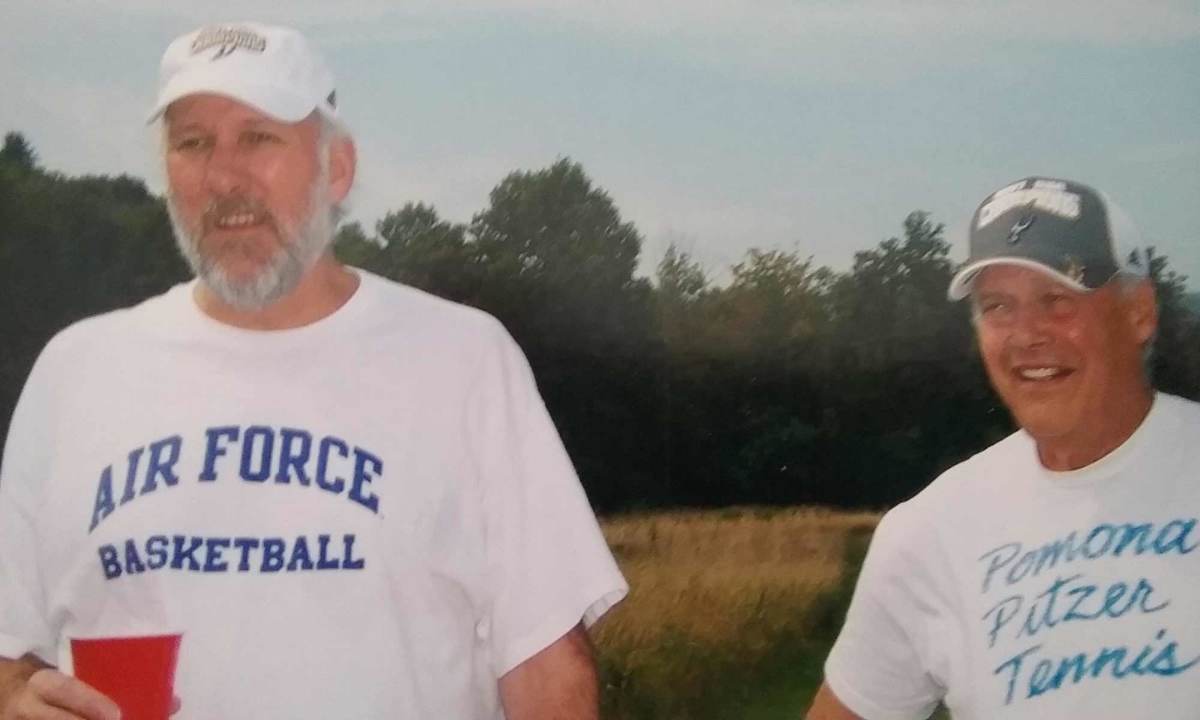

Tong and Popovich were 14 years in age and a generation apart as basketball coaches—Tong was finished and moving on to a new career, Popovich was just getting started. One was the boss and the other was the employee. Their relationship could have been contentious, yet it was very much the opposite. They formed a friendship that lasted the rest of Tong’s life. Curt and Jinx Tong moved back to Massachusetts in retirement and when the Spurs played in Boston, they would spend time with Popovich. (Curt called Popovich "Poppo," his nickname from the Pomona-Pitzer days). In the summer, Popovich would vacation in the Berkshires. Tong attended Spurs’ training camp several times.

When I decided to write about Coach Tong, I hoped that Popovich would participate. Popovich has little use for vacuous banter, but welcomes substantive dialogue. Tong was—and remains—a substantive part of his life. He agreed to talk, which, in itself, speaks volumes. "He’s a great friend, a great mentor,’’ Popovich said in a phone interview last week. "Somebody I love very deeply and miss very, very much.

"I can read people pretty quickly,’’ said Popovich. "Who is full of themselves? Who has gotten over themselves? Who is altruistic and who is not? From the first day I was around Curt, I believed he was a better person than I was. That’s not a humble act or anything, that’s just a fact. His demeanor, his kindness, his love of people, yet at the same time his ability to be disciplined and to have standards, and to demand that standards be kept. That’s a fine line for a lot of people, but Curt did it with grace and intelligence. When you meet a guy like that, you want to be in his presence."

Popovich says it was Tong, with more than a quarter–century as a student and coach at liberal arts colleges, who explained to him the value of immersing himself in the intellectual and social fiber of a vibrant, small campus. "I really enjoyed the campus life," says Popovich. "I enjoyed faculty committees, and I participated in a lot of them. And a lot of the reason is because Curt encouraged me to do it. It made my life so much fuller, and my experience became so much broader than just athletics." Popovich pauses and then broadens the conversational field. "What’s the word? Serendipitous?" he asks. "It’s serendipitous that I wound up in the NBA. But for me, it would have been serendipitous, and just as wonderful, to have stayed at Pomona for the rest of my life. I loved it. I still miss it."

Popovich’s teams rose from hopeless to mediocre, and in the 1985-86 season went 16-12 overall and claimed first place in the Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference, the school’s first title in 68 years of league membership. He took a sabbatical the following year and spent half a season with Larry Brown at Kansas and half with Dean Smith at UNC, and then returned to coach the 1987-88 season at Pomona-Pitzer. In the ensuing offseason, two things happened: First, Popovich was denied a college-sponsored mortgage for which he felt he had qualified. Second, Brown offered him a job with the Spurs. "Sayonara," says Popovich. He talked to Tong before leaving. "He was great," says Popovich. "He said, 'Life is short. This is a great opportunity. Go for it.'"

Popovich took another of Tong’s lessons with him to San Antonio and puts it on display with some frequency. He does not embrace adulation or shrink from criticism and does not allow others to judge his work. He does not suffer fools. "This is what Curt told me," says Popovich. "'Do what you do, do it well and do it with passion. But do not worry about plaudits or condemnation, because both are going to come your way. Whether you’re the manager of the local McDonald’s, the coach at Pomona or Phil Jackson with the Chicago Bulls, you are going to get plaudits and you are going to get condemnation and they’re both false notions. You need to care about how you do your work and how you treat your family and friends. Nothing else matters.

"To this day," says Popovich, "I have never read any articles about any of our championships. I will read an article about Tim Duncan or Kawhi Leonard or Bruce Bowen. My players. But as far as articles that judge 'You’re going to win, you’re going to lose; you’re good, you’re bad.' I have no interest whatsoever. And that’s all Curt Tong."

Back to serendipity, and the curious turns of the road that carry a man from 2–22 at Pomona-Pitzer to five NBA championships. "There are so many who do so well and never get the opportunity to coach D–I or what-have-you,’’ says Popovich. "It’s character that makes people who they are, not the position they hold. Curt Tong has touched just as many people as I have. It’s just that you’ve heard of the ones who I touched."

Tong touched Harry Sheehy, too. Sheehy, 64, is in his seventh year as the athletic director at Dartmouth. He is the best basketball player that Curt Tong ever coached, a spidery, 6'5" guard with leaping ability that belied his physique and a keen sense for finding holes in a defense. He scored 1,449 points in three seasons in the era before freshman eligibility and went on to play for the barnstorming Athletes in Action team.

Like Popovich, Sheehy’s memories trend away from basketball and toward life lessons. Coach Tong’s office in old Lasell Gymnasium was at the front of the building, with a large window that looked out onto the campus. The joke was that Tong knew who every player was dating, just by looking out his window. He also liked to see his players wearing warm hats in the winter. Gerry Kelly, a 1,000-point scorer who played for Tong from '75 to '79, says, "Whenever I would walk past that window, coach would point at his head."

One day, when Sheehy was a high-scoring senior coming off a big game, he walked past the window and Tong waved him inside. "I was feeling pretty good about myself, and I guess it was showing," says Sheehy. "Coach sat me down and said, 'Harry, it strikes me that if you’re really good, you’ll never have to tell anybody.' Man, I went back to my room and flopped on the bed for a long time. That hit me right in the heart."

Most coaches have sayings. One of Coach Tong’s was, "You play Saturday night’s game on Thursday night's sleep." He would say it every Thursday. "We would roll our eyes," says Sheehy. When Tong left for California in 1983, Sheehy was named his replacement as Williams's basketball coach. (Sheehy went on to post a .757 winning percentage in his 17 seasons, and took six teams to the NCAA tournament). "The week before our first game, I gather the team on the bleachers, and what do I say?" says Sheehy. "I tell them they’re playing Saturday’s game on Thursday night’s sleep."

Two weeks after Curt Tong cut me from the team at Williams, he recommended me for a vacant position coaching the junior varsity basketball team at the local high school. I got the gig and spent two years rushing from afternoon classes to Mount Greylock High to coach 14– and 15–year–olds and then rushing back to grab cold food in the dining hall. (One of my players was Tong’s youngest child, a then–bespectacled, brown–haired little boy named Kurt, who is now an adult with three children and a 27–year career in foreign service, currently posted to Hong Kong). Of course there was a reason the job was vacant: We weren’t very good. My Mounties won three games in my first season, but pieced together five victories in the next. It was the most fulfilling experience of my life at the time. I remember every face. Coach Tong knew that would happen and the experience nearly pushed me into coaching; I chose journalism instead, because... well, who knows why we do anything at 21?

Still, I never fully let go of getting cut from my last real team. Thirteen years would pass. I was on my third job in sports journalism, as a writer with Newsday, covering the NCAA Final Four in Indianapolis. It was 1991, the year Duke upset undefeated UNLV and won the title. College coaches in all divisions, past and present, hold their annual convention at the Final Four and stay together in the same hotel. I went to that hotel Sunday between the semifinals and finals to collect some interviews about the upcoming championship game.

As I scuffled around the lobby I heard a woman’s voice, calling my name. It was Jinx Tong. She gave me a hug and hustled me over to a large circle of coaches immersed in conversation. One of them was Curt Tong. He turned and grabbed my hand, beaming. "Everybody,’’ he said to the group, several of whom I had interviewed in my work, "This is Tim Layden. He’s one of my former players." The words rolled off his tongue so easily, and in that moment, the message finally took hold. To Coach Tong—to any true coach—you were not a star or a reserve, and you were not a player who spent four years on his team or were cut after one season. You were a former player. Period. And then you went on to the more important things in life. (I described my Indianapolis meeting to Popovich. He said, "That’s Curt. Hold that one close. Trust me.").

When the Tongs moved back to Williamstown in retirement, they made a tradition of hosting dinners for the children of Curt’s former players who also wound up attending Williams. The Tongs kept a guest book that dated to Curt’s days at Otterbein. In 2009, my daughter signed the book and flipped back many pages to find her father’s signature from a dinner on New Year’s Eve in 1975.

In that same year I attended a game at Williams with the Tongs. I brought a big coffee table book about the history of college basketball and gave it to Curt as a gift. Jinx brought a photo album with team pictures from the '70s. It was a Saturday afternoon, so the crowd was sparse. You could hear sneakers squeak, referee’s whistles and screens called out as we flipped through pages of the album and identified the faces of boys who had long become men. It was a good day. There were no plaudits and no condemnations. Just a coach’s lesson understood many years after it was taught.