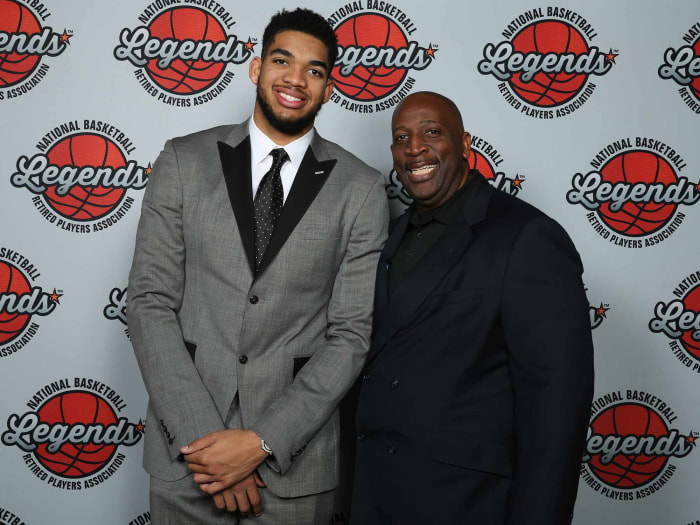

Karl Towns Sr. Considering Lawsuit Against Timberwolves And Their Mascot

The Crossover has learned that Karl Towns Sr.—the 54-year-old father of Timberwolves star center Karl–Anthony Towns Jr.—has been assessing the potential legal ramifications of a significant leg injury he suffered during the Timberwolves home game against the Indiana Pacers on Jan. 26. Towns Sr., who is a retired high school basketball coach, was injured during a timeout with 5:53 to go in the second quarter. The Timberwolves’ prophetically named mascot, Crunch, appeared to lose balance towards the end of a high-speed sledding stunt and hit an empty front row seat next to the aisle. That seat, in turn, crashed into the right knee of Towns Sr., who was sitting next to the empty seat. The elder Towns is now exploring potential legal options, including the possibility of suing his son’s team for negligence.

The use of a sled by Crunch was not something new in the Target Center. It’s also not new for an NBA team mascot, as the Utah Jazz “Bear” has sled down aisles during games in Salt Lake City. Crunch has a routine where, during timeouts, he sleds down stairs in the lower bowl near the court. Crunch isn’t supposed to hit any seats during the slide, but unfortunately for Towns Sr., the mascot did so on Jan. 26.

Towns Sr. suffered considerable pain and was given an ice pack to reduce swelling. The Crossover has learned that while arena attendants encouraged Towns Sr. to leave the game and seek care at a local hospital, he refused to do so. Towns Sr. believed that his son—the NBA’s Rookie of the Year in 2016—would notice his father’s absence. In turn, Towns Sr. reasoned, Towns Jr. might worry about his father’s health and not play as well. Towns Sr. stuck around for the rest of the game, but by the end, his knee had begun to swell considerably and he couldn’t put any weight on it. Arena attendants provided Towns Sr. with crutches. He hobbled out of the arena and was taken to a local hospital for an MRI.

Three weeks later, Towns Sr. was spotted at All-Star Weekend’s Rising Stars Challenge, in which his son played. Towns Sr. was on crutches at the time and appeared to be moving in pain.

The safety and legal risks of NBA game presentation

There is no debate that the injury suffered by Towns Sr. was caused by an accident. Outside of a child or an elderly person, probably the last person Crunch would ever want to injure is a parent of the team’s franchise player. An accident like that could lead to a swift firing of the performer who suits up as Crunch.

Yet just because Crunch didn’t intend to injure Towns Sr. doesn’t mean Crunch complied with the law. When a court determines that an accident was caused by negligence (unreasonable conduct), the negligent person can be ordered to pay the injured person money for any physical damages, pain, suffering and loss of income.

State Of The Process: Should We Still Trust In The 76ers?

Also, if Crunch did act negligently, even though the performer who was playing Crunch would have committed the negligent act, the performer’s employer would likely be on the hook as well. Employers are usually responsible for employees’ negligent acts when those acts are committed within the scope of the employees’ job. While it’s uncertain if the performer who played Crunch was an employee of the Timberwolves, the Target Center or the Target Center’s operators, or whether he or she was an independent contractor retained for a specific performance, either way, more “deep pocketed” defendants than Crunch himself/herself would likely be responsible for the injuries. This is particularly true if the team or arena operators pre-approve stunts and performance choices, and if they facilitate the mascot’s routines.

The Timberwolves’ use of a mascot who interacts with fans is one example of “game presentation.” This refers to the marketing concept that fans should be entertained at all times during games—including during timeouts, halftime and other stoppages of play. Game presentation can create lucrative sponsorship opportunities for teams. It can also enable teams to more effectively capture and maintain the attention of modern-day fans, many of whom are prone to look at their smartphones during breaks in play. Game presentation also makes games more appealing to young children, some of whom find contests and mini-games during timeouts more entertaining than the games themselves.

Game presentation also, unfortunately, creates all sorts of safety hazards for fans. At many NBA games, for example, the mascot and members of the dance team use air cannons to propel t-shirts far into the seats. When that happens, ticketholders jockey for the best position to make a catch. Sometimes such jockeying can lead to aggressive behavior by fans who suddenly become obsessed with catching a $5 t-shirt. This is problematic because there’s no opportunity for a ticketholder to “opt out” of the jostling if a flying t-shirt happens to be directed at him or her. Mascots launching items has led to litigation in other leagues. Most notably, the Kansas Royals spent six years litigating against a man who suffered a serious eye injury when hit by a hot dog that had been launched by Sluggerrr, the Royals’ mascot (the Royals ultimately won the case).

Teams and facility operators can defend themselves in injured fan litigation by arguing that fans assume the risk of injury while attending a sporting event. The risk of fan injury is often expressed as a disclaimer on a game ticket. Also, public address announcers frequently warn fans to pay attention at all times. Assumption of risk has often, though not always, proven to be successful defense for baseball teams against foul ball injuries. It is usually less effective in other types of fan injury litigation. Still, when teams and facilities can establish that they met basic duties of fan safety, such as by showing they adhered to industry standards, teams and facilities are normally found not liable for fan injuries.

Forecasting the possible lawsuit Towns Sr. v. Crunch and Timberwolves

Back to Towns Sr. and Crunch. Fans attending NBA games are usually not exposed to a substantial risk of injury. While occasionally an NBA player might go tumbling into the front row for a loose ball—such as LeBron James did to Celtics ticketholder Bill Belichick on Wednesday night in Boston—fans at NBA games typically aren’t worried about a basketball or other piece equipment violently flying into the stands. This suggests that an NBA fan might not be expected to be as attentive to environmental dangers as would a fan at an MLB game.

For that reason, perhaps Towns Sr. could effectively assert that he did not assume the risk of injury caused by a haphazard mascot routine. He arguably wasn’t exposed to a common risk at a particular sporting event, like a foul ball at a baseball game or even an errant puck at a hockey game. He was injured by a mascot performing a high-speed slide. If Towns Sr. sues, a court would want to know whether the performer who was playing Crunch has injured other fans, whether fans have complained about the safety hazards posed by Crunch and whether Timberwolves and Target Center officials had internally expressed concern about Crunch’s acts. Similarly, whether officials knew or should have known about the dangers posed by this performer would become key factors in any pretrial discovery.

The Craft: The Invisible Superpowers Of Steven Adams

The Timberwolves and Target Center would likely offer a number of defenses. They would portray the incident as a fluke accident that was unforeseeable. Along those lines, if the performer who was playing Crunch has done many slides without incident, the defendants would have a stronger argument that this was simply a freak occurrence and not the result of unreasonable conduct. The performer having extensive safety training and impressive performance credentials would also enhance the defendants’ chances. Further, if Towns Sr. has attended many Timberwolves games, he was likely aware of Crunch’s routine, at least to some degree. The team and arena might assert that Towns Sr.’s familiarity with the routine means he might have done more to safeguard against it.

The most likely scenario is that Towns Sr. and interested parties, most notably the Timberwolves, resolve the matter out of court. They could do so through mediation, where a neutral mediator would review the dispute and proposes a settlement that, if all parties accept, would end the matter. The reality is that the Timberwolves do not want to litigate against the father of the team’s franchise player—such a move would obviously damage the team’s chances at keeping Towns Jr. for the long haul. It stands to reason that a deal could be had long before anyone appears in court.

Michael McCann, SI's legal analyst, provides legal and business analysis for The Crossover. He is also an attorney and a tenured law professor at the University of New Hampshire School of Law.