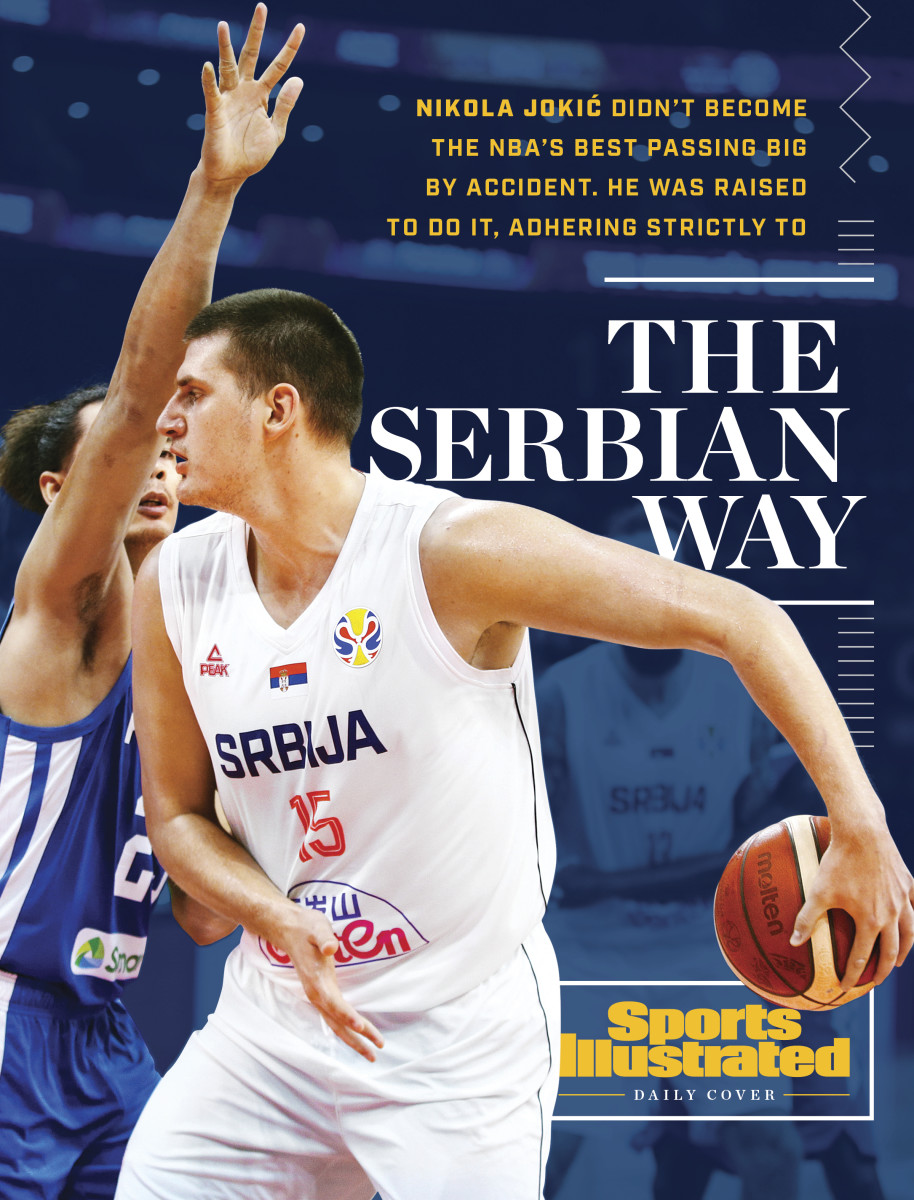

The Making of Nikola Jokić

It was not Nikola Jokić’s most impressive play of the season, or even of the night. He held the ball on the right wing as the Nuggets got situated for a second-quarter possession against the Jazz. The game had the dawdling vibe of February basketball, and, scanning the floor, Jokić seemed almost to be yawning, which would have been of a piece with his popular image. The 7-footer is the NBA’s lethargic genius, with ample arm flab, a summer-camp buzz cut, molasses-slow feet and a clairvoyant understanding of the patterns of the sport. He looped an overhead pass to the center of the lane, unoccupied for the moment by players on either team. All of a sudden Jamal Murray, Denver’s point guard and Jokić’s chief sidekick, burst to the rim. An instant before, Murray had initiated a backdoor cut—one unperceived by everyone but Jokić. The ball landed in Murray’s hands; he pump-faked and finished the layup; the Utah defenders blinked at one another. “He’s seeing everything!” Nuggets broadcaster Scott Hastings said of Jokić, which wasn’t exactly true. Replays showed that when he made the assist, he was looking off into the distance of the backcourt.

Most NBA centers go their entire careers without throwing a pass as prescient as that. But for the 25-year-old Jokić it is standard: not only expected but also relied upon. Maybe no team since the early Stephen Curry Warriors has so depended on one player’s talent for a singular facet of the game. Curry’s shooting had the effect of stretching defenses to the point of snapping, creating angles of attack for himself and everyone else. Jokić’s ball movement achieves similar ends by other means. He flicks skip passes to suddenly wide-open shooters; he steers bounce passes through thickets of interior defense. That night, in a 98–95 Denver win, Jokic had 10 assists to go with 30 points and 21 rebounds. His season averages, impressive as they are—20.2 points, 11.4 boards and 6.9 assists—only partially get at his centrality to the point-piling Nuggets offense. “We feel that we have the most dynamic, best facilitator [and] best young playmaker in the NBA,” Denver coach Mike Malone has said.

Jokic’s peers—the rest of the globetrotting twentysomethings poised to inherit the league from Curry, James and Durant—come from far-flung locales but have traceable hoops lineages. Giannis Antetokounmpo is a lengthier LeBron, collapsing defenses on one end and pinning shots to the backboard on the other. Luka Doncic’s step-backs and lobs are James Harden’s. But even in this hypercomparative era of sports analysis, the consensus is that we’ve never seen anything quite like Jokic. While the NBA takes an indefinite pause for the coronavirus, the question, for fans as well as team-builders looking for a replica, is: How did basketball’s most idiosyncratic superstar come to be?

The Serbian philosophy of basketball development descends from the late Aleksandar Nikolic, a physical fitness instructor at the University of Belgrade who, during the eddy of relative peace between the end of World War II and Yugoslavia’s deadly dissolution in the early 1990s, developed into Eastern Europe’s answer to James Naismith. The Professor, as he came to be known, traveled across the U.S. before the 1964 Olympics and studied under dozens of college coaches, including UCLA’s John Wooden. He returned home with a collection of set plays that featured nearly infinite offshoots and variations, and that therefore required players who could recognize an opportunity and enact, on the fly, a sudden change of plan.

To that end, Nikolic pushed his pupils to excel at each discrete part of the game, traditional requirements be damned. Guards learned to pivot in the low post, big men to dribble upcourt with their off hands. Decades before “positionless basketball” became chic in the NBA, Nikolic’s Yugoslavian national team whirred through European tournaments, a marvel of adaptability. His crowning achievement was a gold medal in the ’78 FIBA World Cup, but his legacy, 20 years after his death, remains the methodology by which he won it, which still serves as the backbone of Serbian basketball.

“It is a system that gives unbelievable results,” says Ognjen Stojakovic, a native of Belgrade and the Nuggets’ director of player development. Stojakovic arrived in Denver as a video coordinator in 2012, two years before Jokic was drafted. He describes an approach, adhered to with religious zeal in a nation of 8.7 million, in which players under the age of 16 follow a strict protocol, regardless of size. “At that age, they don’t have positions,” Stojakovic says. “They need to know how to play face to the basket, side to the basket, back to the basket. You teach them technique and also tactic, which means you need to understand when to use different kinds of moves.” On the one hand, Stojakovic’s description calls to mind dusty instruction manuals containing diagrams of knee-padded figures demonstrating the outlet pass and triple-threat position. On the other, the regimen seems almost calibrated to produce what modern parlance terms unicorns—oversize, no-longer-mythic players capable of doing everything that can be done.

Only three foreign countries have produced more NBA players than Serbia’s 23:

Canada (pop. 37.7 million) with 41, France (65.3 million) with 26 and Germany (83.3 million) with 25—and those who reached the league from the six nations that once made up Yugoslavia (20.9 million) number 73, including Doncic. A high-water mark for Serbia came in the early 2000s, when Vlade Divac dropped mid-post dimes and Peja Stojakovic (no relation to the Nuggets’ staffer) canned three-pointers for Kings teams—beloved in NorCal and Novi Sad—that suffered annual playoff heartbreak at the hands of Shaquille O’Neal, Kobe Bryant and the Lakers. (The low may have come in 2003, when the Pistons used the No. 2 pick on Darko Milicic, a 7-footer whose name became shorthand for the risks associated with spending a high draft spot on a player untested by the rigors of U.S. basketball.) The current crop of Serbian NBA players runs a familiar gamut of complementary specialists. Bogdan Bogdanovic, a shooting guard with Sacramento, knocks down threes. The 7' 4" Boban Marjanovic is a functional backup in Dallas and an icon of NBA Twitter.

Into this history steps Jokic, who plays like a Professor Nikolic fever dream. It is not just the collection of attributes and skills: the sternum-bruising shoulders, the pillowy midrange jumper and three-point set shot, the functional ambidexterity and probing pivot foot. It is the ease with which he calls upon them. Every MVP candidate now plays multiple positions over the course of a game; in the age of LeBron, it’s part of the gig. But Jokic—jab-stepping a 7-footer out of his shorts then ramming to the rim, or faking a drop-off and flinging some blind absurdity to an I-swear-he-just-materialized-there cutter—seems to play them all at once. Technique and tactic, the manual made mind-blowing.

The freedom was born of restriction. Jokic has a knack for the pick-and-roll, which he runs interchangeably with Murray; according to PBP Stats, they are the only two teammates to tally more than 100 assists to each other this season. But players in Serbia’s development system were forbidden to run the bedrock set: It was seen as a shortcut that locked trainees into roles instead of encouraging all-around acumen. “If you know how to read situations, set plays are easier,” Stojakovic says. “That’s a short version of Serbian basketball.”

The training catalyzed Jokic’s innate playmaking skills, guiding him away from patterned thinking and toward a more interrogative style. He developed a knack for seeing plays not as series of prioritized options—a) roll and finish, b) kick out to a shooter, c) settle in for a post-up—but as sets of interrelated possibilities, of bodies manipulating and reconfiguring space. Nikola Nesterovic, a Serbian chess grandmaster and Jokic admirer, sees a predictive imagination at work in his countryman’s game. “We can see something, we’re planning our moves a couple of moves ahead,” Nesterovic says. “When Jokic sends the ball where there is no player”—lofting that pass behind Utah’s defense—“that’s kind of a chess move. He knows someone will be there.”

If the young Jokic was in some ways an ideal student, the embodiment of the Nikolician basketball worldview, he could also be a frustrating one. In 2012, he left his youth team in Novi Sad, near his hometown of Sombor, to join Mega Basket of the Adriatic League. Dejan Milojevic, Mega’s coach, remembers his first impression of the 17-year-old. “I knew immediately that this guy’s incredibly talented,” Milojevic says, “but his body’s in terrible shape.” Jokic’s doughy physique has endeared him to Stateside fans, but early on his couch-potato tendencies—as a teenager he had a three-liter-a-day Coca-Cola habit—presented serious concerns. Worried that Jokic would injure himself going through full Mega practices, Milojevic assigned him to work with only a trainer for a month to improve his conditioning. Afterward, Milojevic stashed Jokic on the club’s junior team.

“He wasn’t in the greatest physical condition, but he was very coachable,” says Branislav Vicentic, Jokic’s junior coach. “He liked to work on his game.” It is the type of compliment generally attached to gym-rat types, but with Jokic it suggests something else: the prodigy’s fascination with the object of his talent. One day, Vicentic assigned a dribbling routine involving complex maneuvers with two balls, one that even seasoned point guards might have trouble picking up. But Jokic happily executed everything asked of him, without any mistakes. “So I said, ‘Come on, you’ve practiced this, you’ve done this,’ ” Vicentic recalls. “He said, ‘No, this is the first time.’ ”

Jokic won the junior circuit MVP award that season. The next, it was on to the big club, where his practice-floor accomplishments stood out just as starkly. Milojevic remembers a drill Mega ran designed to speed up decision-making. The team’s big men would catch the ball on a pick-and-roll and base what came next on signals from a courtside coach. If an assistant held up an odd number of fingers—one, three or five—the player was to pass; an even number meant finish. Jokic did so well that he necessitated a ratcheting-up of the arithmetic. First the assistant used two hands, then Milojevic stationed another coach on the opposite side of the court, requiring Jokic to look in both directions and calculate the total fingers before making his move. When this failed to prove any more difficult, Milojevic moved the session along.

“With this drill, every player could become a decent passer,” Milojevic says. “But Nikola’s passing isn’t decent—it’s extraordinary.”

The difficulty lay not in building Jokic’s skills but in persuading him to deploy them fully. The basketball culture that shaped Jokic, founded on selflessness and team play, kept him from exerting an influence commensurate with his talent. “This is part of the ethos of the former Iron Curtain countries,” says Fran Fraschilla, a FIBA analyst for ESPN. “There’s a certain amount of socialism in the game of basketball. It’s taught that, ‘We share everything.’ ” In the 2013–14 season, coming off the bench for Mega’s senior team, Jokic played well but with a teenager’s reluctance; he would dance past his defender on one possession and spend the rest of the quarter shuttling the ball from teammate to teammate. Milojevic prodded him, seeing glimpses not just of an occasionally creative post player but of a 7-foot point guard who could also wreak havoc on the block. “Whenever he grabbed a rebound, I encouraged him to put the ball on the floor,” Milojevic says. “I don’t know how many times he made mistakes, but I knew that I had to swallow [them], because you could see that it was going to eventually pay off.”

Mega struggled the next season, going 11–15, but Jokic emerged, averaging 15.4 points, 9.2 rebounds and 3.5 assists, directing the offense from whichever spot on the court he preferred. “He became aware of what he’s capable of,” Milojevic says. Despite his team’s losing record Jokic won honors as both Adriatic League MVP and Top Prospect. If it wasn’t the outcome he would have preferred—Jokic’s Mega coaches, like those in Denver, remark on his absolute lack of interest in personal statistics or accolades—it resonated in some way with the Professor’s tenets. Everything can be taught, even a needed dose of selfishness. “At Mega,” Milojevic says with a true believer’s conviction, “we do what is best for the player.”

It is true that at a certain point talent is its own fuel. Jokic isn’t only a product of instruction; Vicentic and Milojevic both use the word natural, liberally and egolessly, in describing their former pupil. His 253-pound physique, still the butt of jokes on Twitter and Inside the NBA, is stealthily useful. “His body frame is great,” Milojevic says, ample enough to move opponents where he needs them to go. His leisurely pace, too, has its perks. “He’s so slow that his basketball mind slows down and he sees the game in slow motion,” Fraschilla says. “He’s able to make plays because he’s not sped up like a lot of young players are.”

Still, even given his inborn gifts, it is hard to envision this version of Jokic coming from another basketball tradition, especially America’s. Organized youth basketball in the U.S.—specialized, hierarchical, gleefully capitalist—is in many ways the inverse of the Serbian system. Players go to point guard or big man camps and find themselves categorized and ranked against their peers at an early age. The national sporting temperament tends to favor reliability over curiosity, repetition over experimentation. What would it do with someone who sees the court with fresh eyes every trip down?

When the Nuggets brought Jokic to the States after his breakthrough season with Mega—they had drafted him the year before with the 41st pick—his former coaches wondered how he would adapt to the NBA. “I would be lying if I said that I expected he was going to be this good,” Milojevic says. The concern centered not on Jokic himself but on his potential surroundings, on what would happen if he found himself on a team with a less flexible view of the sport. But Denver proved an ideal landing spot, with a young roster to grow alongside Jokic and a coach, in Malone, as willing as Milojevic had been to put the ball in his hands.

In short order Jokic has progressed from League Pass curio to ascendant star to, over last season and this one, a borderline MVP candidate leading a fringe contender.

(At 43–22, the Nuggets ranked third in the Western Conference when play was suspended.) His two-man game with Murray has become one of the league’s toughest covers. Jokic is one player on highlight reels—all those full-court touchdown passes and pratfall fadeaways—and another over 48 minutes. Watch him play long enough and you’ll see the tricks for what they are: not bursts of stand-alone inspiration but extensions of a consistent and deeply ingrained approach. In some situations, a jump hook or kick-out is all that’s needed. In others, the ball has to go between the defender’s legs.

These days Stojakovic’s work with Jokic amounts to maintaining the Serbian syllabus. They go through daily guard-like dribbling routines and rehearse nearly every type of field goal that can be attempted. One-footed shots get special attention; lacking the liftoff of almost everyone else in the NBA, Jokic needs to be able to surprise his opponents with a quick release from anywhere. Asked if they run passing drills, Stojakovic laughs, saying, “That’s his own thing.” Jokic’s success may not prove much of a template. Kids everywhere throw up 25-footers to copy Curry; true improvisation is a taller order. But neither is Jokic the pure anomaly his reputation and YouTube catalog suggest. “Back home, we used to say, “If you want to build a house, your base needs to be big. If you have a big base, you can build a high house,’ ” Stojakovic says. “That’s the philosophy of basketball. You need to have a good foundation in order for them to reach the sky.”