An oral history of the 1974 Steelers, the team that launched a dynasty

Like 1776, the year 1974 saw the founding of a nation. Steelers Nation. That season launched the most productive run in the NFL’s Super Bowl era -- four championships in a six-year span -- roughly 40 years after team owner Art Rooney Sr. founded one of the most perennially hapless franchises in league history.

Now, another 40 years have passed, and that first Steelers’ Super Bowl team is remembered and celebrated as the group that finally broke through and turned the tide for what became one of the NFL's most successful and iconic franchises, creating one of the most enduring love affairs between a city and its professional football team. The architect and backbone of that team, head coach Chuck Noll, led the Steelers to those unparalleled heights, and helped Pittsburgh become known as the “City of Champions” in the ‘70s. Noll, who died in June 2014 at 82, remains the NFL’s only four-time Super Bowl-winning head coach, and he and nine of his players from that ground-breaking 1974 club are enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

• NFL Playoff Picture after Week 16 |2015 NFL Mock Draft 2.0

But in 1974, no one knew the NFL’s eventual team of the decade was about to conquer the league and scale football’s mountaintop. That Steelers season started in inauspicious fashion with a three-man quarterback controversy, a halting 1-1-1 record after three weeks and a sense of locker room turmoil. It was anything but a four-month coronation in Pittsburgh, and even the abundant and overflowing depth of the roster -- fortified that year by the greatest infusion of talent in NFL draft annals -- could not completely smooth out the bumpy ride the 10-3-1 Steelers endured.

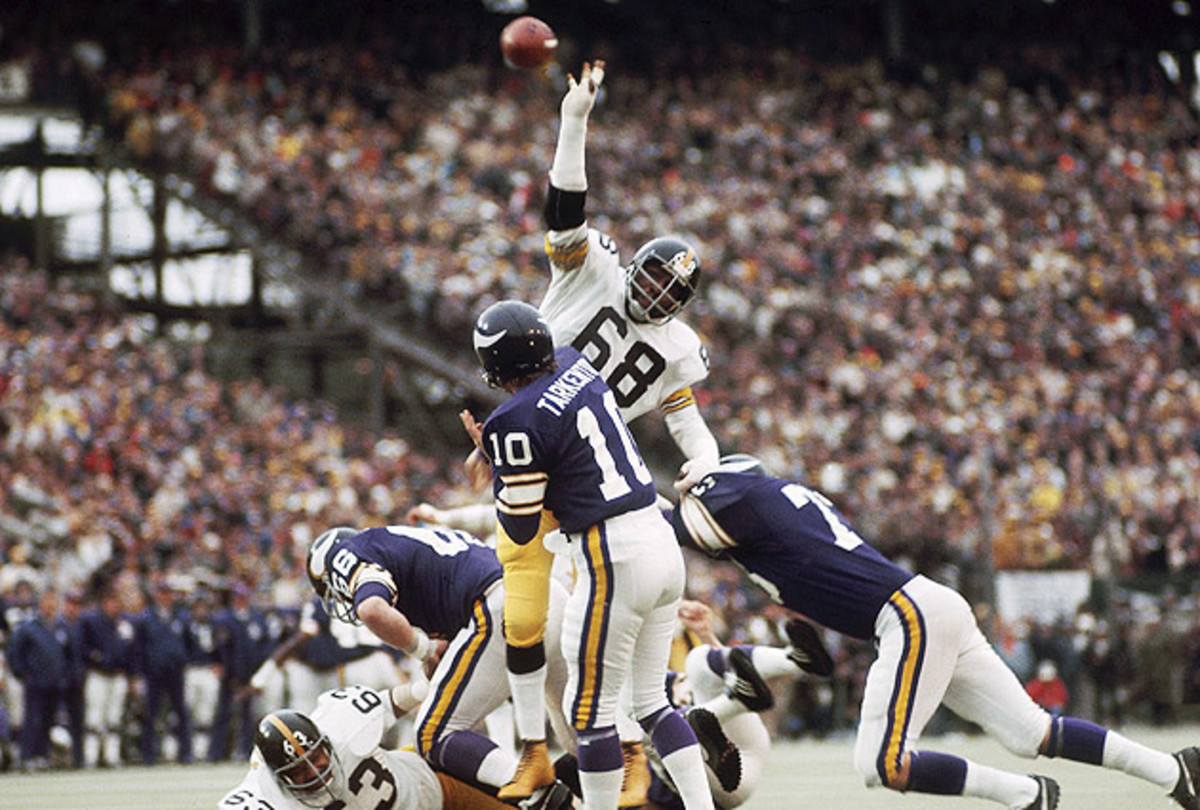

Nothing came easily for the ’74 Steelers, but they persevered, endured and eventually triumphed in Super Bowl IX, outclassing the Minnesota Vikings 16-6 on a damp, cool Sunday afternoon at New Orleans’ Tulane Stadium in January 1975. It was a cathartic victory for the city of Pittsburgh and a success-starved franchise that had been lost in the proverbial desert of losing for almost four decades, and it represented just the beginning for one of the NFL’s all-time legendary teams.

Here’s a retrospective of that initial Steelers’ Super Bowl championship through the eyes and words of 10 members of that club. Sports Illustrated Senior NFL writer Don Banks interviewed the former Steelers one weekend in November at both the team complex and Heinz Field in Pittsburgh, where a 40th anniversary celebration of the 1974 Steelers was held.

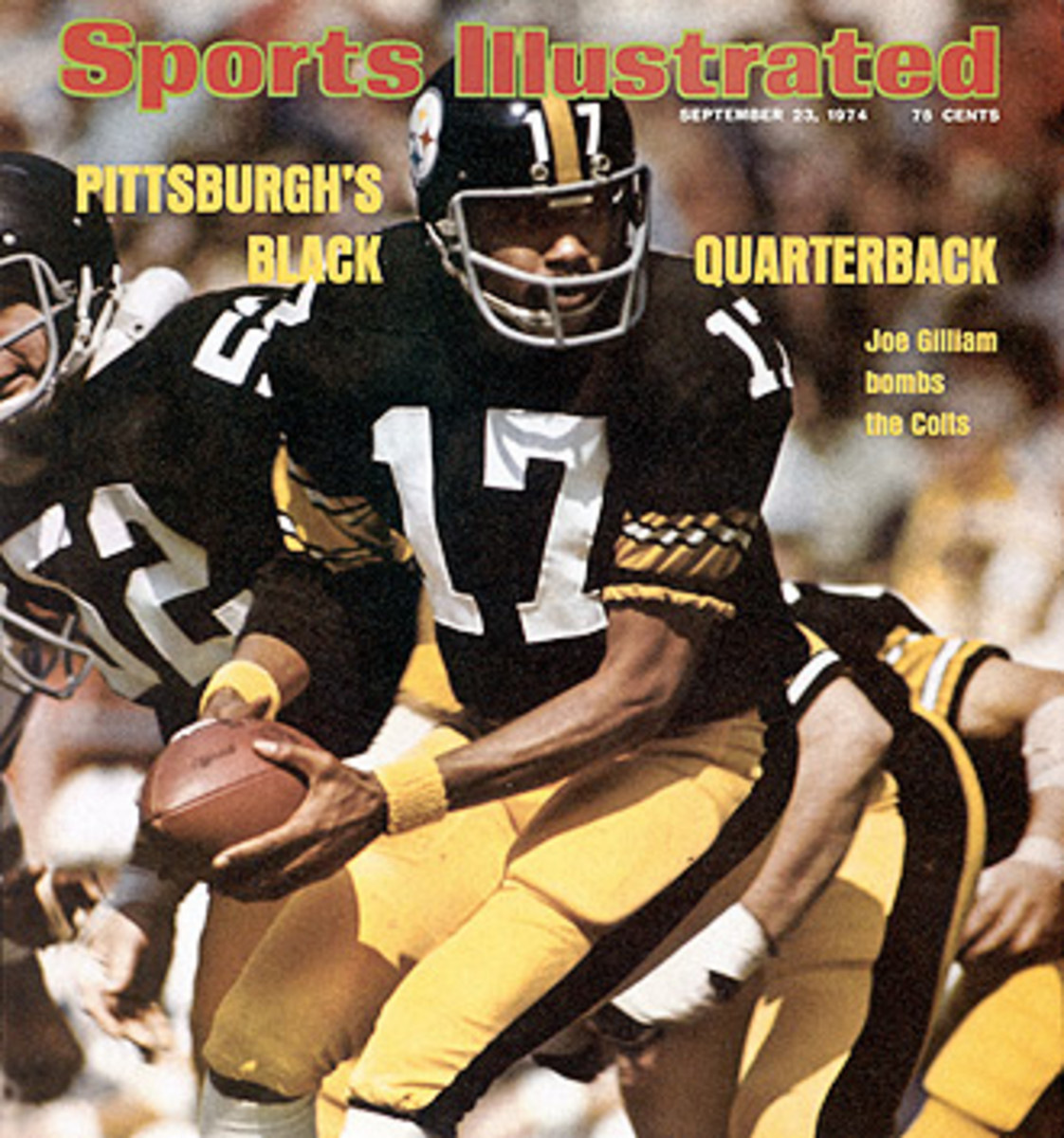

• In July and August of 1974, a veterans-only players’ strike marred the start of training camp and the six-game preseason, with teams playing the first two weeks of the exhibition schedule with almost all-rookie rosters. Not every veteran honored the picket line, however, and among those was third-year, third-string Steelers quarterback Joe Gilliam, who reported to Pittsburgh’s Latrobe, Pa., training camp site and proceeded to impress Noll with his arm and athleticism. The strike ended on Aug. 10 without a new collective bargaining agreement between the NFLPA and the league, and when Pittsburgh starting quarterback Terry Bradshaw suffered a late preseason injury, it opened the door for Noll to turn to Gilliam for the mid-September season-opener at home against the Baltimore Colts. He was the first African-American quarterback to open a season as an NFL team’s starting signal-caller. (Gilliam’s first game, a 30-0 home rout of the Colts, landed him on the cover of Sports Illustrated: ‘Pittsburgh’s Black Quarterback’ reads the unarguable headline. He was benched in favor of Bradshaw in Week 7 and wouldn’t return to the starting role again.)

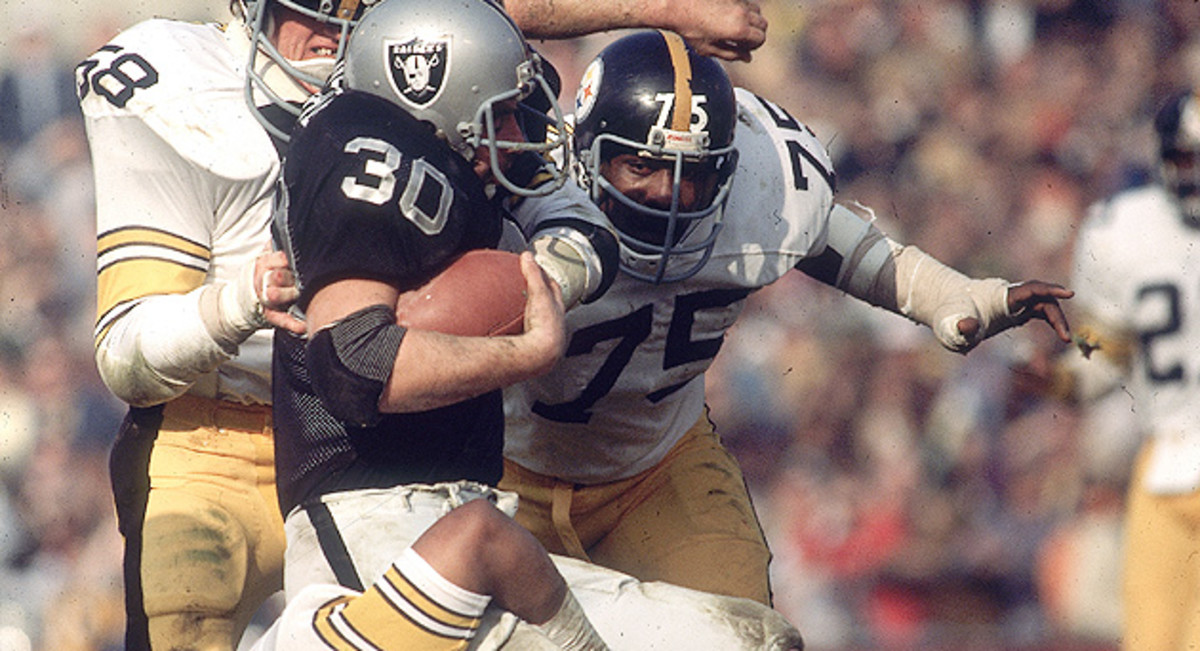

And that wasn’t the only controversy the Steelers had to endure. Defensive tackle Joe Greene, the team’s biggest star and the cornerstone of the emerging Pittsburgh Steel Curtain defense, actually walked out on the team in early December, frustrated by the state of the Steelers '74 season in the days following a 13-10 home loss to Houston in Week 12. Even with Pittsburgh in first place at 8-3-1 after that defeat, Greene seethed about the slow pace of the Steelers’ development as a Super Bowl contender. To prove his point, he went so far as to pack up the contents of his locker and announce he was leaving.

Mike Wagner, safety: It was a mess in 1974. You go back and think about all that was happening, it was really a mess.

Rocky Bleier, running back: All of it started with the strike. You have a players’ strike and we’ve got people crossing the line, and it was an unknown thing and not a popular strike, either. Because some people didn’t really agree with going on strike, and it caused some tension. Gilliam crossed and ultimately Bradshaw and Hanratty and all of us went into camp.

Cowboys avoid drama in locking up NFC East title; more Week 16 Snaps

: Has there ever been another Super Bowl champion that started three different quarterbacks like we did that year? We went from Gilliam to Bradshaw to Terry Hanratty and then back to Bradshaw, and all that happened in the first [11] games of the season.

Bleier: It wasn’t a blueprint for a Super Bowl championship season at all. You think back and you gloss over it, “Oh, it was a great season. We were 10-3-1 and made the playoffs.” But it just doesn’t jell. It doesn’t jell. And we’ve got some dissension in the locker room and all this controversy that’s going on. Later in the year, Joe [Greene] quit, or threatened to quit, and that upset things again.

Joe Greene, defensive tackle: I wanted us to be further along than I thought we were. At some point in time over that season, I became very frustrated, really right at the end of the season, after that Houston game.

[pagebreak]

Receivers coach Lionel Taylor saw that Greene was determined to quit and caught up with him outside, and the two sat in Greene’s car for a while, letting the emotional sixth-year veteran vent about his impatience with the team’s inability to join the ranks of the AFC’s elite championship contenders like Miami and Oakland. Thanks to Taylor’s timely intervention, Greene eventually returned to the locker room and the team.

Greene: But after that, once I got past that, all signals were go.

Bleier: Joe obviously thought the New England game was what turned it, because that was the game after he got talked into coming back. He felt it started to finally click for us when we won that game, and then beat Cincinnati at home [27-3] the next week.

Forty-five years after last AFL season, rivalry with NFL still resonates

Wagner:

Glen Edwards, safety: When you talk about those Steelers defenses, everybody talks about Joe Greene, Joe Greene, Joe Greene. But that ain’t all it was. You know who the man was in the [defensive] huddle? I was. [Edwards was voted team MVP in ’74 even though Greene won NFL Defensive Player of the Year.] I was constantly getting on guys, pumping them up, that was my thing. Everybody got competitive on that defense. Guys would be fighting over interceptions. They made Joe out to be the team leader, but as players, we said, “Hell, who made Joe our spokesman?”

John “Frenchy’’ Fuqua, running back: You guys. I’m going to tell Joe you said that.

Bleier: Those last two wins [New England, Cincinnati] were very important, just from a belief system. Because there’s a time, whether it’s collective as a team or as an individual, where you decide whether you’re buying into what Chuck is preaching. You either say, “OK, we’re on the right track and I believe in where he’s taking us,” or you start to lose faith in his leadership. At some point, we bought in.

• The ’74 Steelers largely are remembered for producing the most ridiculously successful draft class in history. Four future Hall of Famers were selected in Pittsburgh’s first five selections: Swann out of Southern Cal in the first round, middle linebacker Jack Lambert from Kent State in the second round, Stallworth out of Alabama A&M in the fourth round, and center Mike Webster out of Wisconsin in the fifth round. And often forgotten is safety Donnie Shell, who arrived that summer as an undrafted collegiate free agent and went on to be a Steelers' standout for years. Greatness, however, was not immediately apparent on any front.

Lynn Swann, wide receiver: We came to a team that had been in the playoffs two years in a row and one of those years they were one game away from the Super Bowl. So I don’t think they looked at us and said, “OK, here are the missing pieces.”

John Stallworth, wide receiver: As rookies, we expected at some point the veterans are going to come in, and we’d see what happened then. I’ve got a receivers coach, Lionel Taylor, telling me, “Those moves you’re making right now, when [fifth-year cornerback] Mel [Blount] gets here, you won’t be able to do that. Those won’t work on Mel.”

I can remember us going down to New Orleans for a preseason game during the strike, and Mel’s from that state and he went to school down there, and Mel comes to the sideline during that game. I’m looking at him and he’s the biggest defensive back I ever saw. And I thought to myself, “You know, I might not be able to do those moves.”

Swann: I think people forget how important that time was for us during the strike, getting all the reps. We were able to get way over the learning curve in terms of the system and our assignments.

Wagner: After the strike we [the veterans] came into camp with only a few weeks left, so the rookies had been playing a lot and had been coached up and had been there for a while. And guess what? They were pretty cocky and rightfully so. The veterans kind of came in here like, “OK, it’s time to take care of business.”

Swann: There were probably some questions: Why’d the Steelers draft these guys? Look at Jack Lambert. He doesn’t fit the mold [at 6-foot-5, 218 pounds]. But all of a sudden, Jack Lambert ends up being a starting linebacker.

Dave Reavis, offensive tackle: It took [1973 Pro Bowl middle linebacker] Henry Davis getting hurt [in the preseason] to get him [Lambert] in the lineup. He stepped in and the rest is history. Who know what happens if Davis doesn’t get hurt?

Wagner: Those guys [the rookies apart from Lambert] didn’t play much. They played enough, but not a lot. So the team, the core was there, but what you really saw right away was the depth.

Fuqua: My god, to a great extent, if you went down, you might not get your job back. We had guys who came off our bench who could have started almost anywhere else.

Stallworth: Nobody for certain could tell our draft class was going to be as talented as it was.

Edwards: I’ve got a different opinion. I think ’71 was the best draft they had. Period. Me, Mike Wagner, Jack Ham, Dwight White, Larry Brown, Ernie Holmes. The ’74 draft, those guys put the final pieces in place. But all of us guys from ’71 were early starters. That ’74 draft, those guys had to wait their time and just played in spots at first.

Reavis: Not a bad argument there.

Edwards: I’ve got a legitimate argument. The ’74 class came to a better team than the one we did. Yes they did.

[pagebreak]

• To a man, the Steelers said Noll was the team’s real leader, the unquestioned authority figure for a group that grew into one of the game’s greatest, most doggedly determined teams over the course of the ‘70s. Noll was almost always stoic in demeanor, and was cold and distant in the eyes of some players. But he didn’t rule his team by fear or intimidation. Once the nucleus of Pittsburgh’s dynasty was in place, he was superb at knowing how to keep his players focused on the task at hand, believing you won with self-starters. Between 1972-79, the Steelers won the old AFC Central seven times in eight years, winning 10 or more games all but one of those years, and going to the playoffs eight years in a row. Noll coached the Steelers for 23 seasons (1969-91), but never got the team back to the Super Bowl after earning those four rings in six seasons.

Wagner: I did not fear Chuck. I respected him. But I was probably wary.

Reavis: That’s a good word for it, wary. He kept you wary.

Wagner: I just think it’s like you’re wary of your parents. You know you love your parents but you just don’t know what you don’t know.

Bleier: I think the father figure thing was very strong, but did you fear Chuck? No, you didn’t fear Chuck. He wasn’t that type of guy you feared. But you didn’t want to let him down. The fear was he’d get rid of you. He wouldn’t have a knee-jerk reaction. He’d give you enough rope to hang yourself. But if you were a special teams kind of guy and you weren’t making curfew, or you were late, you were screwing up. He wouldn’t hesitate to give you the boot. That was the fear.

Swann: I think the worst part of the job for Chuck was probably having to cut players. Though he did it and knew he was going to cut most of the guys when they first came to Pittsburgh. But I don’t think it was ever something he felt really comfortable with, so he tried to protect himself. Chuck wasn’t a guy who got close to the players, but he was close to all his assistants.

Stallworth: As a rookie, I don’t think I ever understood Chuck Noll the whole season in ’74.

Fuqua: Did we ever really know him? We never really got a chance. I don’t think he ever really opened up and let us understand what his thoughts were. He was a perfect CEO. He made our coaches, our position coaches, the authority with us.

Edwards: I do remember [longtime Steelers defensive coordinator] Bud [Carson] used to worry us to death, aggravate us to death. Because he was scared of Chuck. Bud would always nag you, “You’ve got to do this, you’ve got to do that.” You’d say, “Bud, just chill out. Everything is all right.”

Fuqua: Well, he had the man on his ass. That’s what I’m saying. And that’s what a good CEO does.

Swann: From what I gather from some of the assistants, there was probably nothing Chuck wouldn’t have done for them to help them, both professionally and personally in terms of being better people, better coaches, better husbands, better fathers, better Christians. Chuck was there for them. But with us, Chuck was more about “We drafted you, we think you have talent, we’re paying you to do a job, you’re adults, and I’m going to treat you like adults. Get it done.” And we did.

Edwards: Chuck was a no-nonsense guy. When you were on that field it was strictly business. After practice sometimes he’d josh and play with you, and try to run the ball like he could still play or something. But he was a no-nonsense guy. In my mind I think all of us learned to play that way for him.

Stallworth: Chuck Noll was stoic. He talked in truths. He’d talk about finding your life’s work. He’d talk about let’s go out and have fun, and there’s fun in winning, and I was just trying to understand that [during my rookie year].

Wagner: Chuck, throughout his career, at least when I played for him, he wanted everything even keel. So when we won, he didn’t want us too high. He’d say, “OK, enjoy the victory but tomorrow we have to get back to work.” And if we lost a game, particularly if it was one we thought we should have won, it was like, “Hey, we’ll take a look at film, everybody tend to your wounds and we’ll take care of business when we get back.”

Stallworth: In my rookie year he told me, Let’s go out and have fun. So I catch a pass and I use a move I used when I was like in the sixth grade. I thought it was hilarious because it worked, and I’m laughing on the field, and I come to the sideline and he said, “What are you laughing about?” And I’m thinking, “You just told me to have fun. I’m having fun.”

Bleier: If Chuck had a dog house, it was in his own world, his own mind, as to who might be in it. There were certain expectations he had of his people, things he wanted from you. I don’t think they were big expectations, but he wanted a certain performance and he wanted you to do your job.

Fuqua: To a great extent, at least on my behalf, when we lost, I just tried to stay out of his way. Out of sight, out of mind. Noll wasn’t one to holler at you or anything like that. But perhaps his biggest weapon was his silence.

Reavis: And his look. His eyes, he could look right through you.

Franco Harris, running back: I’m sure I was in his dog house plenty of times, but that doesn’t take away from how you look back at things later in life and how you viewed him as a player. We were players and they were coaches, but it was very important to have our leaders who got us ready and made a difference.

Edwards: I tell guys all the time, we won because we wanted to win for the coach.

Fuqua: The reality of it is, we were a football team full of players that were out of their f------ minds. You look at the personalities throughout the team, and all of us, we all had a problem in life. And what I think was done well by Noll and the coaching staff, they dealt with those problems.

Harris: In time you get to appreciate more than you do as you live in the moment, and even though it didn’t seem that way then, Chuck really did care about his players and what they did and about their contribution to the team. Everything was about the team and he really did relay that sort of feeling.

Fuqua: I’ve got a great Chuck story. In 1970, it’s the opening of Three Rivers Stadium. It’s the last exhibition game of the preseason and it’s Friday night, bed-check, 11 o’clock. I’ve got my eventual wife-to-be in the room with me and [a bottle of] Jack Daniels. Usually the assistant coaches did bed check. Not this night. Knock-knock. “Who is it?” “It’s Coach, John. Just want to check on you.” So I grab her and put her in the bathroom, then I go open the door and run back in the bed because I’ve got nothing but my briefs on.

Coach comes in and he’s got a damn album and headphones with him. He knows the stereo equipment I used to have and he comes in and says, “You mind if I listen to this song while I’m here?” And I’m saying, “Oh, s---.” He puts it on and puts the headphones on and I swear it was the longest four-and-a-half, five minutes of my life. He’s standing there and he’s listening to it, taking his time.

We had an exhibition game against the New York Giants the next day, and he said, “Well, you know we’ve got your former team, tomorrow.” And I said, “Yeah, I’m ready, Coach.” And he’s walking to the door, and man I’m sweating because the bathroom’s right next to the door. He passes by the bathroom door and he just stops, and I said, “Oh, s---.” He gets in the bathroom and I hear him pulling the curtain open and all he says is, “Young lady, you have to leave. The man has a ballgame.”

[pagebreak]

• Noll’s approach to the team’s quarterback situation, hopscotching between Gilliam, Bradshaw and Hanratty, drove some players a little nuts early in the year, given they saw the talented but erratic Bradshaw, the first overall pick in 1970, as the team’s long-term starter. But the Steelers’ coach won major points with his players with the way he handled Super Bowl week in New Orleans.

And his deft touch in the “Big Easy” wasn’t even his best move of the postseason run. That actually occurred a few weeks earlier, when he put his rarely-used motivational skills to work. The Steelers won their playoff-opener at home in convincing fashion against visiting Buffalo, routing the Bills 32-14 and holding Bills star running back O.J. Simpson to just 49 yards in his only career playoff game. The other AFC playoff game that weekend pitted the two-time Super Bowl defending champion Dolphins (11-3) at Oakland (12-2), the teams with the best two records in the NFL that season. It was an epic game, won dramatically by the Raiders 28-26 on a play that memorably became known as “The Sea of Hands’’ catch. Oakland head coach John Madden, in a moment of candor he probably later regretted, said after the game that the two best teams in football had just met -- a full week before Oakland’s date against the visiting Steelers in the AFC Championship Game.

Wagner: He [Noll] wasn’t a rah-rah coach. The biggest motivational pregame speech he might give us was, “Hey, today’s fun day. Let’s go out there and have fun. That’s what we work hard all week for.” So if you were looking for a rah-rah type environment or one where if we’d lost a coach was pointing the finger or challenging our manhood and our effort, Chuck Noll wasn’t that kind of coach.

Greene: Coach Madden made that comment about the two best teams in football already playing, meaning the Raiders and Miami, and Chuck took offense to that. He said the people in Oakland think the best teams played yesterday. But the Super Bowl is not played for another two to three weeks, and the best team in football is still in this room.

Andy Russell, linebacker: And he’s yelling it, and that wasn’t Chuck at all. That was so out of character.

Joe Greene was sitting right next to me in one of those desk chairs, and he stood up and started walking like he was going out to the field, with the desk chair still wrapped around him. He was ready to play right then. He wanted to go out and kick somebody’s ass right then. And I was like, “Gee, I wonder if Chuck’s getting us ready too early?”

Greene: Case closed. Nobody had a chance after that.

The Steelers defeated the Raiders 24-13 in the AFC Championship Game, scoring 21 points in the fourth quarter.

Russell: When we got to New Orleans [for Super Bowl IX], Chuck said, “OK, I want you go out the first couple nights, no bed check, and get this city out of your system.” Which the Vikings didn’t do.

Harris: It was brilliant on Chuck’s part to say, “Hey, we’re here, so you guys go out for a few days and enjoy yourself. But then it’s time to go to work.” That was great. We were able to go to restaurants and enjoy the city, try new things, new food.

Russell: By Wednesday, we were begging for a bed-check. We were ready to get down to business and get that game played.

Harris: Nobody was beating us that day. Even though Minnesota had been there before and they talked about how they were favored, it didn’t matter.

• There was one more seminal moment for those Steelers in the pre-Super Bowl build-up, and it occurred in the tunnel that the two teams were sharing before the start of pregame introductions. The talkative Edwards spotted a former Florida A&M teammate -- rookie reserve offensive tackle Charlie Goodrum -- in the tunnel and tried to say hello and make small talk with his opponent. But Goodrum ignored him completely.

Edwards: We were ready. We were real cocky, matter of fact.

Wagner: [You] were in particular.

Edwards: We’re down in the tunnel waiting to come out, and this guy I played with in college was there with the Vikings. I tried to go over and say, “What’s up, Home?” He wouldn’t acknowledge me. So I said, “OK, y’all better buckle up, because we’re going to bring it.” And soon enough, we brought it.

Reavis: I think you said, “We’re going to kick your ass.” That’s what you said. “We’re going to kick your ass.”

Greene: I remember Glen saying, “Buckle up, big fella. This is going to be a hard day for you guys.”

• And it was. The Vikings never scored on offense and gained all of 17 yards rushing in the game, won by the Steelers 16-6. Pittsburgh led 2-0 at the half after L.C. Greenwood was credited with a safety, and the Steelers' defense forced three Fran Tarkenton interceptions, including one each by Wagner and Greene. Harris rumbled to the game’s MVP honor, with 158 yards rushing and a nine-yard touchdown on 34 carries, and defensive end Dwight White played heroically after being hospitalized for much of the week, and losing 17 pounds, due to what has been reported as either pneumonia or food poisoning. The Steelers, the NFL’s long-time doormat, had become champions, and a dynasty had begun.

Today, the Steelers’ six Super Bowl victories lead all NFL teams, and their eight Super Bowl appearances are tied with Dallas for the most all time. But in the almost 40 years that have passed since that January day in New Orleans, the appreciation for what the 1974 Steelers accomplished has grown exponentially among the men who comprised that rather unlikely championship club.

Wagner: My recollection of the game was that, particularly on defense, we were a perfect match against that offense in Minnesota. It was going to be strength against strength. And we knew we could probably overcome their weaknesses.

Fuqua: You guys had built up a reputation of being so dominant on defense. I very seldom ever worried because of our defense. It was like, what, it wasn’t three-and-out? When a team got a first down it was a shock. We had the best defense in the league. And you guys only got better as you went along. We had complete confidence in you. And championships are won with the defense.

Wagner: I don’t think anybody was worried about not being able to handle them, which is kind of strange in the Super Bowl. But the defense was just so confident. We weren’t even worried. The biggest concern I had was the stupid football field was so slippery that I [thought I] was going to slip and fall on some big plays.

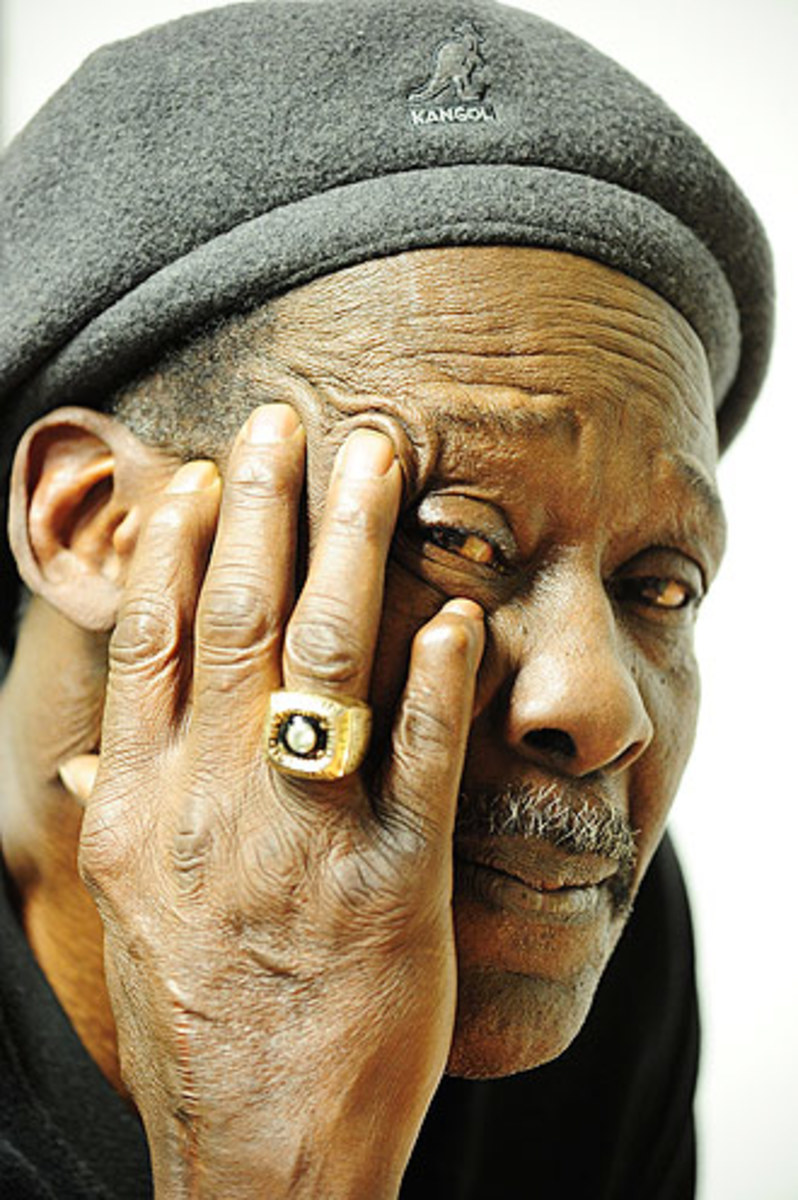

Greene: For me, the first one will always be the sweetest. Having been 1-13, having to digest a lot of that SOS stuff -- Same Old Steelers -- with the franchise’s losing history, that was very, very special for the Pittsburgh Steelers to win the Super Bowl. Because the football world was kind of surprised. So it was nice to surprise people.

Stallworth: My first two years, all I knew was going to the Super Bowl. Hindsight being what it is, you can look back on it and you can see how awesome that defense and that team was. But sometimes in the middle of it, at the moment, you don’t always know what you have.

Greene: To do it again [in 1975] was great. Then to do a third time was greater [in 1978], and the fourth [in 1979] was our legacy.

Harris: It wasn’t an easy season at all, but we were able to pull it together. To me that was the year that really set the stage for the true character of our team. What we were going to stand for. What we were about. We overcame the early season issues, and then we got focused. The main thing is it really showed the character of our team and the character that we needed for what was to come. And to me, that year really showed who we were.