A woman fell from a stadium, a man saved her; here's what happened next

The phone fell first. Glenn Israel heard it hit concrete a few feet away from him and crack. He looked up and saw a young woman sitting on a railing 45 feet above him, crying.

Everybody in the vicinity that day was just passing through. A full NFL stadium feels like an enormous party, with thousands celebrating in the same way. But it is also like a small city. On this 2013 day, four days before Thanksgiving, O.co Coliseum was filled with the dreams, job stresses, loves, addictions, plans, undiagnosed diseases, appetites and relationship woes of more than 60,000 people.

The Oakland Raiders had lost to the Tennessee Titans, 23-19. In an indoor batting cage near the Raiders’ locker room, Oakland coach Dennis Allen was beginning his postgame press conference with an injury report.

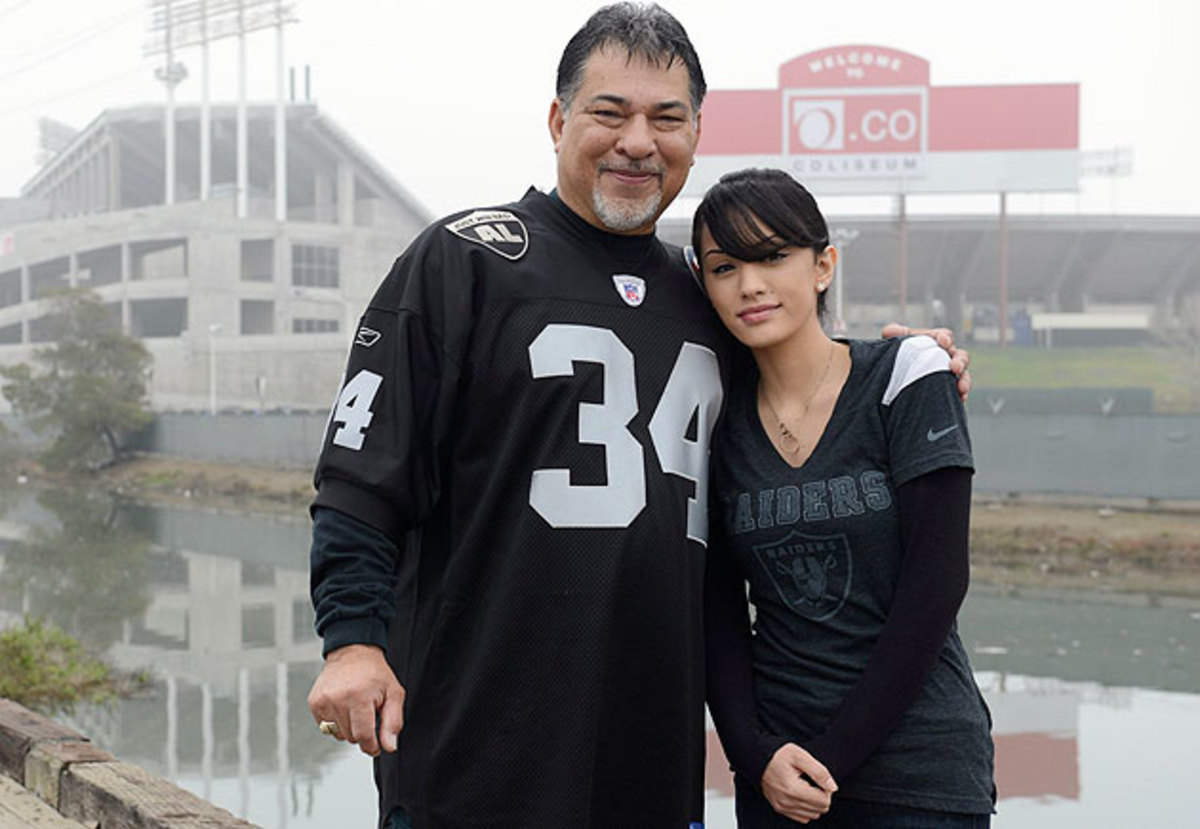

Israel had just posed for a photo with his friend Donnie Navidad by the Al Davis Memorial Flame, named for the late Raiders owner. Former Raiders star Bo Jackson had lit the flame before the game, and Navidad wore his Jackson jersey, hoping to get an autograph. He never got one, so on their way out, he and Israel asked a woman there to take their photo.

Navidad walked back toward her to pick up his camera. Israel did not join him, because he has a bum ankle, and the fewer steps he takes, the better. He was walking toward the parking lot when the phone landed.

Fans saw other fans looking toward the sky, and they looked up too, at the horror unfolding above Section 300. The woman was dangling now, her arms spread back behind her, clinging to the railing. Even if she wanted to pull herself back up, the physics were almost impossible.

"No, no, no!"

"Don’t jump! Don’t jump!"

A fan named Tom Rodriguez heard the screams and looked up. By day, Rodriguez sells spray-on protective coating for the beds of trucks, but when he attends Raider games he is a temporary celebrity because of his outfit: white mask, silver mohawk helmet and full Raiders uniform, including pants and pads. Fans kept stopping him to take his photograph, which is why he was still by the flame instead of in the parking lot when the phone dropped. He ripped off his mask and helmet to prepare to catch the woman.

Navidad was standing next to Rodriguez. He glanced back at Israel and said: "Do you think she’s gonna jump?"

Israel said, "She’s coming down right now."

She plummeted 45 feet in less than two seconds. Rodriguez reached to his right to save her, but he had no chance. He was too far away, and she was falling too quickly.

Navidad was her only hope. Forty-three years earlier, Navidad was in Marine boot camp, crawling under a wire screen as rounds of gunfire exploded over his head, learning to react immediately to the unforeseen, and here it was, in the form of a woman’s body descending toward him at 35 miles per hour. He tried to brace himself and fall backward as she landed on him, to absorb the shock. She ricocheted off him and landed a couple of yards away, where she landed on concrete.

Blood pooled around her head. Rodriguez stood over her and thought she might be dead. Navidad appeared to be knocked out.

Police rushed to the scene. So did Israel, who got Navidad’s attention and asked him simple questions. What’s my name? How many fingers am I holding up? Navidad answered correctly. His left arm was quite bruised, and his ankle would bother him for a month, but those were his only injuries.

The woman had no identification on her. Nobody in the crowd knew who she was. Navidad thought he heard her say a single word, ever so gently, right before she hit him: "Momma."

She was rushed to Highland Hospital in Oakland with major neck, spine and facial injuries and admitted as a Jane Doe. Police picked the pieces of her phone off the concrete, got the number off the SIM card, and ran it through several law-enforcement and public databases and contacted the phone’s service provider, and turned up a name: Brittany Nicole Bryan of San Jose. Twenty years old.

Navidad was a local-news hero, celebrated in that brief window before TV stations move on to the next day’s show. He read a few stories about the incident and was stunned by the reader comments. People wrote that if this woman wanted to die, he should have let her. Or he should have sold movie rights and made money off it.

Or, on an ESPN.com story: "You know your team sucks when your fans can't even wait to get home before they off themselves." And: "The lady should have just finished the job and not exposed kids or other people to her mental illness."

Tom Rodriguez read the comments, too, and the man who attended the game in full costume got so angry that he posted a comment himself:

To all you dumb people who are talking smack about us losing, when I was there trying to help save a young girls life with the man who got hurt, people shouldn't be talking SMACK. This was serious and you wouldn't know or feel the same if you were in the same situation, I was there when she fell on the man next to me.....It was not something to JOKE about because we lost the game. I am just happy that they are both alive. So Keep Your Stupid Comments to your SELF.

They did not Keep Their Stupid Comments to Themselves, because Brittany Bryan was not even a real person to them, just an anonymous character on the Internet, grist for the sarcasm mill. Even her family did not know what happened; her boyfriend, who had been at the game, thought she went home, and her mother and sisters assumed she was with her boyfriend.

Her sister Vicky came home from a Mexican vacation with a gift for Brittany (small turtle and fish figurines) and a more expensive one for herself (a silver and turquoise bracelet), and looked forward to seeing Brittany. Her sister Bernadette saw a headline about a woman jumping off the Coliseum after the Raiders game and clicked on another story. The next day, they learned their sister was in the hospital and might die there.

Brittany always thought of herself as Daddy’s girl, and with this father, who wouldn’t? Larry Bryan was 10 kinds of fun, eager to make the kids laugh, desperate to make them feel loved. He treated Brittany’s older sisters, Bernadette and Vicky Fox, like they were his own daughters, even though they have a different father. On Christmas, gifts covered the entire living-room floor, and adventure always seemed just a few minutes away. Larry was the rare gambler with the reputation for winning more than he lost, and he loved taking his family to Las Vegas, or to a hotel in San Jose to swim and play video games. Sometimes he would look them in the eye and wink.

Even his job seemed fun: buying and selling jewelry and other collectibles. Sometimes he would drive the kids to antique stores to sell a necklace or two. They were stunned when he was arrested on New Year’s Eve, 2006, for multiple burglaries. The accusations followed a pattern: Larry broke through windows of million-dollar homes or sliced open screens. He stole jewelry, watches, foreign currency and a few other valuables, and left the electronics. That day, 14-year-old Brittany watched her mother Joy bury a brown bag in the backyard. Joy would be found guilty of being an accessory and concealing stolen property.

The court sentenced Larry to 37 years in prison. Brittany quickly entered a program that would allow her to graduate from high school early so she could get a job. Larry worried about her future. Her sisters tried to take care of her, but Brittany thought they were acting like her parents instead of her sisters. She became an emotional wall, giving one-word answers to innocuous questions.

At 16, she became pregnant, and she waited five months to tell her family, so nobody would try to talk her into an abortion. When Brittany finally shared the news, Bernadette took her to the restaurant where Brittany worked and gave her an informational packet about adoption. Brittany understood the impulse -- adoption might be best for her and the baby -- but decided to keep the baby, a girl named Lyla, born a week before Brittany turned 17. She wanted Larry to meet Lyla. He never did. He died in jail, in his sleep, after battling heart problems. He was 58.

Now here she was, 20 years old with no wallet on her, just another Jane Doe to Internet commenters but Brittany Bryan to her family. Doctors induced a coma to help save her life. A few weeks later, she woke, with no idea how she ended up in the hospital. Bernadette told her she dropped off the top of the Coliseum after the Raiders game. Brittany searched the Internet for local news reports about it, and she heard newscasters talk about a young woman attempting suicide and a heroic ex-Marine saving her life, and she thought: "Why did this happen to me? I was so happy."

Brittany Bryan sits outside a Starbucks in San Jose, Calif. Almost a year has passed. The book she has been reading is on the table: The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong.

She feels better now than she did a few months ago, partly because a piece of her skull is no longer embedded in her abdomen. Doctors put it there as part of a craniotomy, a procedure that allowed them to perform brain surgery while retaining the bone from her skull.

“It looked like I was pregnant on half of my stomach,” she says. “I could feel it and it was really hard. I couldn’t talk because I had a breathing tube in my throat. I was pointing at it, like: 'What’s going on?' They were saying, ‘It’s your head.’ Imagine how I’m feeling. 'What do you mean it’s my head? How did it get down there?'"

Her sisters kept vigil at the hospital, sleeping on a cot in Brittany’s room. The hospital gave her a computer-generated assumed name, Paul 51, in case the media tried to find her. Family members had to show their driver’s licenses to prove they were on an approved visitors list, so they could go in and see a woman who looked like a stranger. Bernadette recognized only her eyelashes, which are distinct. Everything else looked as computer-generated as the name Paul 51.

Brittany’s right hand was broken, her left heel was shattered and bones in her face were fractured. Doctors gave teaspoons of hope surrounded by piles of caveats: We can’t promise this will work. Don’t get your hopes up.

They said even if she survived, she might never seem like herself again. But she does. She emerged from the coma and the surgeries physically whole, or as close to whole as anybody could dream. Oakland’s Highland Hospital is known for treating trauma victims, often because of gunfire and other violent crimes in Oakland, but even at Highland, Brittany’s case stood out. Doctors from other floors of the hospital visited her and called her "the miracle patient." The moment her breathing tube was removed, she looked at the family members in the room and noticed who wasn’t there.

"I miss Lyla," she said, and she started crying.

Her embarrassment was overwhelming. She was reluctant to talk to anybody. How do you explain dropping 45 feet off the top of a stadium? Her friends didn’t know about the incident (the media had not used her name) and they wondered why she was ignoring them. Finally she told a few: "I had a really bad accident." This is how she refers to it, as "my accident."

Suicide? Her family was skeptical. It never occurred to her that the woman might be her sister. Vicky wondered if there was "some hidden, severe depression that we had no idea about," but she saw Brittany every day and thought she had never been happier. Her relationship with her new boyfriend seemed strong. She loved being a mom.

Yet there she was at Highland, literally shattered and also drugged and confused. The idea that she attempted suicide was so farfetched in her mind that she wondered if somebody had pushed her. But she didn’t remember what happened, let alone why.

"All these people, not just the news reporters, all these people that were talking about it were just so sure of themselves,” she says. “There are 100 witnesses saying the same thing, and it’s them against me and how I feel."

Somehow, her phone still worked after the fall. But for three weeks, she couldn’t remember the lock-screen code. Then one day it came back to her: 8779. She could use the phone to make calls, but the screen was broken, and eventually she just bought a new one.

The moments before the accident have come back to her, too -- not all of them, certainly, but enough to give her some sense of what happened. She gave her wallet to her boyfriend so she wouldn’t have to hold it in the restroom. She got lost coming out of the restroom, which was not as unusual as it sounds. She is one of those people who is known, within her family, for her almost comically awful sense of direction. She once came out of the restroom at a San Jose Sharks game and couldn’t remember where her seat was, and it happened at a San Francisco Giants game, too, but she found her way back to her seat.

This time, Brittany couldn’t figure out where to go. She had been consuming alcohol all day, starting with Jello shots at a pregame tailgate, and she was drunk and disoriented. She tried calling and texting her boyfriend but couldn’t get through.

As she stood in a concourse area behind section 144, a man named Kimani Crum saw her crying and tried to help. She said she was looking for her boyfriend, her cell phone was dead and she did not know where her seat was. Crum gave her some suggestions on how to find her boyfriend and left.

She tried to call her mom to pick her up. Her phone was dying. She looked for a place to charge her phone as thousands rushed out of the stadium. Somehow she ended up at Section 300, which is half a football field and two levels away from Section 144. Section 300 was also closed, which may have been appealing to her. She has anxiety in crowds sometimes.

Once she got past a rope barrier blocking off the stairway, there was nobody to stop her. Police would find a single set of fresh footprints in the dust along the edge of the tarp covering the seats.

She remembers "climbing some kind of stairs ... it’s kind of a blur." She may have walked upstairs because everybody else was going down, and this was a chance to get away, or maybe she was just hoping to get a better signal in the postgame cellular haze.

Down by the Al Davis Memorial Flame, Crum looked up and saw her climbing over the railing. He realized this was the same woman he had tried to help.

What was she thinking as she sat there? She wishes she knew. She has heard that when people are drunk, they don’t hear words like "don’t," and perhaps her ears filtered that out of the crowd’s pleas: Jump! ... Jump! She may not even have realized she was four stories above concrete. She may have let go of the railing out of frustration, or to feel momentarily free. She will probably never know.

The last thing she remembers was wishing her mother Joy would take her home. This would explain the only word that Navidad heard her say before she landed: "Momma."

Some witnesses said she jumped and others said she fell, but she thinks she was too drunk to know the difference. This is the one thing she knows for sure: Whatever she did, she never would have done it sober. Rodriguez, who watched her fall, insists that if she had pushed herself away from the railing, she would have sailed past him and Navidad.

Brittany’s best friend’s mother is a recovering alcoholic, and before the accident, Brittany would sometimes join her at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. She did not talk much, because she was a drinker, and "I didn’t want to be a hypocrite. It was just nice and refreshing to hear other people’s stories, just to listen."

After her fall, she thought about joining a support group for people with traumatic-brain injuries, but decided that wasn’t right for her. She prefers the AA meetings, and hearing stories there convinced her that alcohol triggered the incident at the Coliseum. She says she is not an alcoholic. She says she did not get drunk often, even before the accident, and never felt compelled to drink every day. But like many 20-year-olds, once in a while she would drink with her friends, especially at a concert or sporting event, with no limit in mind and no worries about consequences.

Her story is not one of addiction. It’s about impairment, and it is an uncommon variation of a common theme. Two nights after Brittany sat for her SI interview, St. Louis Cardinals outfielder Oscar Taveras climbed in his car in the Dominican Republic with a blood-alcohol level of .287, more than five times the National Transportation Safety Board-recommended limit of .05. Taveras drove into a tree, killing himself and his girlfriend, Edilia Arvelo. And last summer, after former Auburn tight end Philip Lutzenkirchen died in a one-car accident, tests showed his blood-alcohol level was 0.377, which may explain why he decided to get in a car with a driver whose blood-alcohol level was 0.17. The driver also died.

It is harder to understand a woman dropping off the top of a football stadium, unprompted by anyone else. But alcohol-related deaths occur every day to people who are not driving and are not alcoholics. According to a 2012 study by the Center for Disease Control in the United States, four drunk pedestrians a day are killed by cars.

"It could be your first time drinking," Brittany says. "Anything can happen."

Her story may be hard to believe, but at least one man understands how alcohol can push a person outside the bounds of normal behavior. In the 1980s, Donnie Navidad was a Marine reserve, training at the Pohakuloa Training Area in Hawaii, drinking boilermakers with his Marine pals: A shot of Wild Turkey with Schlitz malt liquor, and why stop at one or two?

"I’d try to outdrink the rest of my partners," he said. "Some of the craziest ----. You’re drunk, but you just keep drinking."

Navidad would climb palm trees on the Big Island until he was 30 or 40 feet above the ground. He easily could have fallen, broken his back or his neck, and been a different character in one of these stories.

"You know, you do crazy stuff when you’re drinking," he says. "It kind of dares you. It gives you that feeling, to dare you to do it no matter what the outcome is."

Glenn Israel injured his ankle in the Navy, moving 500-pound bombs around flight decks during a 10-year stint. He served in Vietnam, which is precisely what Donnie Navidad envisioned doing when he tried to enlist in the Navy out of high school in 1970. Donnie’s dad had been a Navy man. But the Naval recruiter asked him to wait a week, and so he joined the Marines instead after taking a one-page test that would change his life, and eventually save Brittany Bryan’s.

His wife Lora says he "thinks like a Marine and acts like a Marine," from his serious nature to his ability to always make her feel safe. Sometimes it’s like he just walked out of boot camp last week. He can still make a Swiss harness seat out of rope, a skill you don’t need in daily American life, because "[t]here are things that are in you that will never leave you." But there is one thing this Marine never did.

Ask Navidad if he served in Vietnam, and his choice of words is telling: "I didn’t get to go." Lora thinks that bothered him; he was a Marine, but he never really did what Marines were trained to do. Then one day he posed for that photo by the Al Davis Memorial Flame, and the Navy vet told the Marine: She’s coming down right now.

"You are trained to react under those kinds of conditions," Navidad says. “It’s just a reaction. You are in a civilian mode, you are enjoying life, and you see this body falling ... are you going to let this human life splatter in front of you? Come on. Had I let that happen, I’m a wreck."

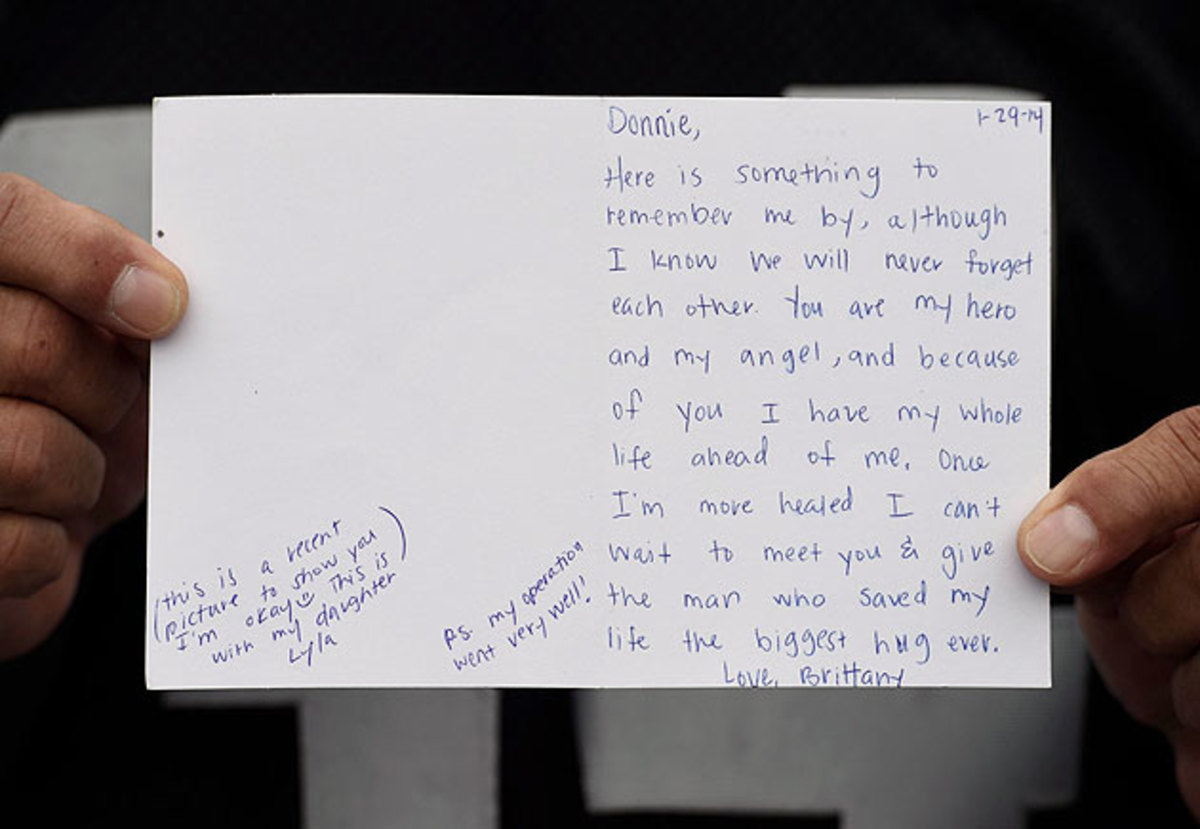

When Brittany left the hospital, she sent Donnie a thank-you note and a picture of her and Lyla. The picture sits on a shelf in the Navidads’ house alongside family photos. Lora says the placement was intentional.

"When you save somebody’s life, you are kind of bonded to that person," she says. "To him she is, and will be, a very important part of his life forever."

After a Raiders-Chargers game in October, Donnie pointed up to where Brittany had dangled. His brother could not believe anybody survived. He is right to be amazed. Brittany probably hit Donnie with at least 1,500 pounds of force.

Lora has seen a different Donnie since the accident. He is more outwardly compassionate, more conscious of the people around him, more outgoing because of the attention. The decision that could have killed him brought him peace. "He is much better for it," she says. Israel agrees: "He’s mellowed out a lot since that happened."

Donnie is proud he saved Brittany’s life, but he still wishes he could have saved it better, more cleanly: "The only thing that really bothers me out of this whole ordeal is I didn’t get to block her into my body. She bounced." In the first moments afterward, he wondered if he had failed. He saw the blood around her head and asked his friend Israel, "Is she going to be OK?"

She is OK. More than OK. She says she truly was happy before, but she was also coasting, finding excuses not to go back to school or pursue a more ambitious career.

"Honestly, I feel a little bit better than I did," she says. "I’m just happier. I feel like it taught me a lot."

The girl who wouldn’t share anything with her sisters just opened her life to Sports Illustrated. Bernadette and Vicky say they are closer than ever, they talk about everything, and they all dote on Lyla, who is 4 years old now and has a sense of humor that reminds them all of Larry, especially when she looks adults in the eye and winks.

In September, Brittany celebrated her 21st birthday in San Francisco with her sisters and a few friends. She wore the silver and turquoise bracelet that Vicky bought in Mexico; Vicky decided, after the accident, that she would rather give it to Brittany than keep it for herself. They went to the Tonga Room and Hurricane Bar, where Brittany drank her ceremonial first legal drink. Then they went back to their room at the Omni, where they danced and sang. Brittany drank a single glass of champagne, resisted any more, and felt lucky.

Brittany just started classes at San Jose City College. She is thinking about becoming a nurse. She would not have considered that career before the accident because she was scared of administering shots. But some of the nurses at Highland brought her such comfort and joy, and she wants to bring that to others. The nurses told her she can get accustomed to needles. One of them showed her proper technique: Pinch the skin a little harder than you think is necessary, then insert the needle, and the patient barely feels any pain at all.