Though often overlooked, Broncos' Harris is now one of NFL's top CBs

DENVER—It was supposed to be the game of Chris Harris’s career. Almost a year removed from ACL surgery, the Broncos cornerback was healthy, ready for the postseason and perfectly suited to defend his likely assignment against the Colts. “I’m made to cover a guy like T.Y. Hilton,” Harris said before Denver’s Jan. 11, 2015 divisional round game—and he wasn’t exaggerating. Hilton is small, quick, shifty, tenacious, the perfect complement to the Broncos’ speedy, relentless corner.

But even as the words came out of Harris’s mouth, he knew Hilton wouldn’t be his man. The Broncos had installed their game plan, and then-defensive coordinator Jack Del Rio had assigned Aqib Talib to the Colts’ no. 1 receiver. There was nothing to do or say. Talib is one of the better cornerbacks in the game, so Harris couldn’t question Del Rio, and he certainly wasn’t going to leak his team’s game plan, however harebrained it seemed.

• NFL division previews: NFC East | NFC North | NFC South | NFC West

During the Broncos’ 24–13 loss, Hilton finished with a team-high 72 yards, and Harris, covering Reggie Wayne and Donte Moncrief, didn’t allow a touchdown. That capped his perfect season—Harris was one of three corners to play more than 500 snaps in coverage and not allow a score—but it mattered little. After the game, the cornerback told the Denver Post that he felt like the Broncos’ season had been “a waste of time.”

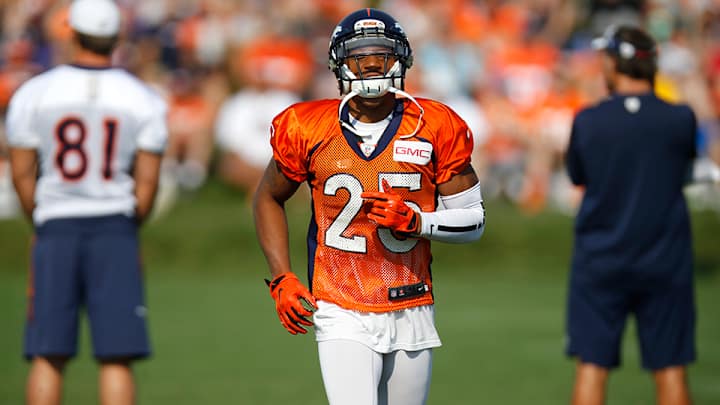

In the months since, Harris’s anger has dulled, and excitement overshadows whatever disappointment lingers. Under new coach Gary Kubiak and coordinator Wade Phillips, Denver’s defense returns the bulk of its talented roster but will switch to a 3–4 scheme heavy on physicality, pressure and blitzing. That will in turn leave the Broncos’ corners on an island in man coverage, where Harris excels. He’s undersized and scrappy, fiery and competitive, the nicest guy in the locker room and the cockiest on the field—and he’s come out of nowhere to become one of the top cornerbacks in the NFL.

--

Four and a half years ago, Kansas’s best cornerback didn’t get an invitation to the NFL Combine. Or to the Senior Bowl, or the East-West Shrine Game. Four years before that, the best player on Bixby (Oklahoma) High School’s 2006 team had exactly one offer to play in college, at a school that at the time had enjoyed a single winning season since joining the Big 12 in 1996. And two years before that, Chris Harris was a basketball player, plain and simple.

On Dec. 15, 2005, Harris and his teammates held their walkthrough before the Oklahoma Class 5A football championship. The cornerback had just had a breakout season, but he seemed distracted. “I can’t wait for tomorrow night to be over,” Bixby’s defensive coordinator at the time, D.J. Howell, recalls Harris telling him. “Because then I can get back to basketball.”

Nonsense, insight out of balance in latest set of talking points around NFL

The coach was accustomed to such comments from Harris, who quit football once in middle school and pondered doing so again before his junior year of high school. The game had always come second, until the spring of 2006. By that time, Harris had offers to play basketball at Texas A&M Corpus Christi and Tulsa, but Howell thought he could drum up interest from football programs, especially those visiting to take a look at Bixby’s standout defensive end, Jared Glover. Howell wouldn’t let up, telling Harris he had a chance to be something special. One day, it clicked. “I’m a football player, aren’t I?” Harris asked his coach, and Howell sighed with relief. “Yes, you are.”

From that moment, Harris honed in on football, developing the kind of technique only year-round attention to the game can grow. He’d always been the smartest player on the field, but in his senior year, he learned the little things: the footwork, the field placement, what to look for at the snap. Meanwhile, Howell lobbied to visiting recruiters, but only Kansas’s Bill Young bit. The Jayhawks would be Harris’s only offer, and off to Lawrence he went.

Unbeknownst to Harris, Kansas was desperately seeking a second cornerback to play alongside Talib, then a hotshot senior. The school had brought in a junior college player it though could fill that role, but Kendrick Harper sustained an injury in fall camp, and soon enough, Harris, a virtual unknown, was getting his reps. “Chris was just the most competitive guy out there, basically,” Talib said. “He had quick feet, and he was just so competitive, man, that was the guy I wanted to play with. I immediately started vouching for him with [coach Mark] Mangino.”

• Fantasy football draft kit | POSITION PRIMERS: QB | RB | WR | TE | K | D/ST

That year, Harris started 10 games en route to the Jayhawks’ Orange Bowl berth and win over Virginia Tech. “I thought we’d go to a bowl every year,” Harris said, “but everything kind of went downhill. That was definitely tough. I would say my last two years there were probably my hardest years, because you’re in school, and you’re losing, and it’s just not fun.”

Over his final three seasons, Kansas went 16–21. Mark Mangino was fired after 2009, and when Turner Gill took over, Harris moved to safety. With an eye already on the NFL, the senior thought the switch couldn’t hurt; instead, he figured, it would show teams his versatility. However, February 2011 came and went without a combine invite, and Harris put all his stock in Pro Day, which about 10 scouts attended. He got good feedback, but even then, he suspected he’d go undrafted.

How the top rookie offensive linemen are developing in new NFL roles

He figured right. Thirty-nine cornerbacks heard their names called on the final weekend of April, but not Harris. To make matters worse, the NFL lockout resumed after the draft, so he had no chance to latch on as an undrafted free agent. Instead, he headed back to Oklahoma, but only temporarily. His plan was clear: He’d train at his high school until the lockout lifted, and if no team called, he’d go back to school, get a master’s degree and start coaching.

The months of working out in the sticky Oklahoma summer became monotonous. Weights, conditioning, run stadiums on Fridays. Every night, Harris would return to his mother’s house, a college graduate with his life on hold. “I never wanted to go back to Oklahoma and get stuck there,” Harris said. “That was a lot of motivation to me.”

Throughout the summer, Harris kept in touch with Howell, who, on July 26, 2011, received a text that read, “I’m going to work.” Howell worried Harris had given up on football, that he meant a job away from the game. “Where?” the coach replied. “The Denver Broncos,” Harris typed back.

--

Harris arrived in Denver an undrafted nobody with a chance at the Broncos’ practice squad. Within weeks, he’d made the 53-man roster as the team’s nickel corner. As a rookie, he started four games, then 12 for the 2012 squad that lost in an upset in the AFC Championship game to Baltimore and boasted one of the NFL’s best defenses. Harris’s real breakthrough, though, came in 2013, when he allowed just one touchdown, started 15 games and was Pro Football Focus’s eighth highest rated cornerback.

Still, the way Harris’s season ended that year in some ways negated his step into the spotlight. It was the Broncos’ first playoff game, against San Diego, and in the third quarter, he tore his ACL. Denver survived without its most reliable cornerback in the AFC Championship—thanks in part to Champ Bailey’s return from injury—but in the Super Bowl, it was eviscerated. Harris watched from the sidelines, and that night in New York, he vowed he’d be back for Week 1.

Gary Kubiak on his return to Denver and working with Peyton Manning

Against all odds, he was. In 2014, Harris was limited for exactly one game—he played just 39 defensive snaps in the team’s season opener—and by Week 2, he was at full strength. Harris finished the season as Pro Football Focus’s highest-rated corner, with 49 tackles, one sack, five quarterback hurries, three interceptions and 10 passes defensed. In December, he signed a five-year, $42.5 million extension with the Broncos, making him the highest paid undrafted corner in NFL history, and later that month, he received the team’s Ed Block Courage Award. In conjunction with the honor, coaches played a tribute video, which is when it struck many of Harris’s teammates: Their Pro Bowl cornerback had just finished the best season of his career, and he’d barely participated in the preseason while finishing his rehab.

“(The video showed) what he had to go through, what he had to come back from, the way he went after it, the tenacity that he approached it with, and the performance he’s had,” Del Rio said last winter. “It’s been a special year for him in a lot of different ways.”

Even so, Harris’s Pro Bowl berth was by virtue of player and coach nominations after he was snubbed in the fan vote. When 2014’s All-Pro teams was revealed, he was again disappointed; though he made second team, he trailed Darrelle Revis and Richard Sherman by 33 and 32 votes, respectively, marking one of the biggest gaps from first to second team at any position. And last summer, when the NFL Network revealed its Top 100 Players list, Harris wasn’t included. “That’s just the story of my life,” he said with a smile. It’s also the source of his motivation.

--

Harris is the nicest guy in any locker room. He’s always laughing, and his shrill voice cuts through the noise. He’s religious, a family man. But on the field, Harris is a terror. He talks trash. He dogs opponents. He’s pesky personified, and the worst part about it is he’s always smiling. Talib recalls a late-August afternoon at Von Miller’s house. Members of the Broncos defense were relaxing and playing an NBA 2K video game, most without much thought to lineups or matchups. Not Harris. “Chris, he set up his defense,” Talib said. “He made subs. He had double-teams going to LeBron. He set up the whole game plan. He wasn’t going to lose.”

Time for redemption: Shane Ray out to prove his worth to Broncos

How did he get that competitive? Harris doesn’t know. Always been that way, he said, and relentlessness is his calling card. “The path that Chris had to take has made him the player and the guy he is today,” Howell said. “He’s always been a little underrated, below the radar, and he’s had to earn it. He was better in high school than he was in youth football. He was better in college than he was a high school player, and he’s better as a pro player than he was in college.”

That’s solely a product of Harris’s work ethic. It’s funny; talk to anyone—teammate, coach, opponent—about the cornerback, and the word “talent” rarely, if ever, comes up. It’s not that Harris doesn’t have it, but rather that he goes so far beyond it. “He’s got tremendous quickness, which you have to have to be as great as he is,” Phillips said. “And he’s got speed. But he’s such a great competitor. He doesn’t want anybody to catch anything on him, even in walk-through. … It didn’t take very long to see. You toss a ball to somebody else, and he’ll knock it down.”

With one of the most stacked secondaries in football—Denver sent Harris, Talib and safety T.J. Ward to the Pro Bowl a year ago, and second-year cornerback Bradley Roby is one of the team’s most promising young players—the Broncos will make their name this season on defense as much as they will on Manning’s modified offense. And a full 18 months removed from his injury in a defense even better suited to his strengths than the Broncos’ scheme a year ago, Harris has a chance to be better than ever before, just as he’s been every year of his football career.

Maybe the football world will take notice. Or maybe not. Harris laughs. Doesn’t matter. Being the underdog doesn’t mean he can’t be the best.