Football, Family and Feminism: Ali Marpet's unprecedented rise to NFL

Like all NFL general managers, Tampa Bay Buccaneers GM Jason Licht prepares hundreds of hours for a process that’s distilled into about 42 minutes. By the time the NFL draft arrives in April, Licht has spent about five months soliciting recommendations from his regional scouts, combing through game film for players that pique his interest, interviewing those players and trimming a draft board of about 350 players to around 120.

Since arriving in Tampa Bay in January 2014, Licht has been adamant that these minutes are the key to building the right franchise and maintains a stringent philosophy that the best teams are bred through the draft. Licht seeks a family, not a collection of prized free agent signings.

As the Bucs limped to their pitiful 2–14 finish in the 2014 season, Licht identified his team’s immediate needs: A franchise quarterback and an offensive line that wasn’t a sieve. Logic indicated that Licht would draft proven, low-risk prospects with his early selections, presumably a hulking SEC or Big Ten lineman. But to think that is to misunderstand Licht, a product of Division II Nebraska Wesleyan. He’s got an affinity for the little guys if he feels they can contribute.

And so Licht considered one recommendation from area scout Andre Ford: Ali Marpet was an athletic left tackle from Hobart College, a small Division III school in upstate New York. He steamrolled opposing defensive linemen like bowling pins on run plays and pancaked defensive ends with flicks of his wrists in pass protection. Licht figured this was due to physically inferior competition but kept him in mind, thinking he may be a good late-round selection.

Off the Grid: Growth of mobile QBs, Q&A with Pettine and Manziel, more

Shortly after Licht viewed Marpet's tape, the left tackle received an invitation to the Senior Bowl, the showcase game reserved for the top collegiate seniors in the nation. “I thought he’d flop around like a fish out of water,” Licht says.

Yet here was Ford’s recommendation, the same guy who had blasted 220-pound defensive ends in Division III, now stifling the nation’s top defensive tackles. And when Marpet took the NFL Combine by storm with his 4.98 40-yard dash, the fastest among the group of O-linemen, Licht knew he wouldn’t last until the later rounds of the draft.

The more Licht researched Marpet, the more he came to like about him. And the more he found that his Division III pedigree may be the least interesting element of his personality.

***

So what did Marpet’s background check, the part teams closely examine for every player they consider drafting, tell Licht?

Think back to Kindergarten. “What does your mother do for a living?” the teacher often asks. “How about your father?”

The Marpet children—Brody, Blaze, Ali and Zena—have the most interesting answers to those questions.

“I think I told people my mom was involved in music,” says Blaze, now pursuing a Ph.D. in Ancient Greek and Roman Philosophy at Northwestern. “And then I’d keep it short by saying my dad was involved in fashion shows.”

Marpet’s mother, Joy Rose, is a former musician who rededicated her life to the emerging academic study of Mother Studies, a field rooted in the feminist philosophies of Betty Friedan, Adrienne Rich and Sarah Ruddick. She now runs the Museum of Motherhood. Joy is of the conviction that there is inadequate scholarship devoted to the history of the mother, and since that role is performed by over 80 percent of the female population, it's a field that should receive significant psychological and cultural study.

“The core of my field of work is the universal bond,” she says. “We are all connected because we all have mothers. We exist because we all maintain a connection of some kind. If we’re aware of this connection, can’t we create a better world?”

Before embarking into motherhood and scholarship, Joy was a radiant 1980s blonde with high cheekbones who hailed from Westport, Conn. and moved to New York City to accept a job working at the costume shop at Juilliard. She would abandon the position to join her friends in a renegade punk rock band called Peter and the Girlfriends, which performed in riot gear and wore pink haircuts (Joy still wears a shade of pink in her blonde hair).

It was the arts scene where Joy met Bill Marpet.

A budding documentarian groomed at NYU film school in the late 70s, Bill Marpet eschewed a life of documenting Pamplona’s Running of the Bulls and European political uprisings to pursue filming the fashion industry, where he latched onto the nascent technology of videotape. He would record shows, hunker down in his SoHo apartment and copy his work on two videotapes at a time, a newly efficient mode of mass production in the early 80s.

Word circulated to fashion titans Calvin Klein and Bill Blass that this was the new way to spread their showcases, and Bill became their point man. Whether it was a high fashion show at Bryant Park or a Talking Heads show at the famed CBGB club, Bill captured both the post-punk grime and ostentatious stylings of 1980s Manhattan because he’d mastered a new recording platform. An Emmy and several other awards later, Bill’s company, B Productions, remains essential to the fashion show industry.

“My co-workers were spoofing me the other day saying I was going deaf,” says Bill, a man with a friendly demeanor and luxuriant ponytail. “I told them the only time I went deaf was when I filmed New Order at the Ukranian National Home on the Lower East Side because they didn’t sound check. My ears were ringing for three days.”

Week 15 NFL Power Rankings: Injuries, upsets shake up AFC’s best

The two paired up to film In and Out of Love Affairs—a cheeky, delightfully 80s pop ballad that was an MTV Basement Tapes winner in 1984. They would eventually marry and, three kids later, move to Hastings on Hudson, a Manhattan suburb dubbed by many as the "Brooklyn of Westchester County."

“Four kids in five years,” Joy says. “I’m a goal-oriented person. With three boys to start, it was like raising horses at times.”

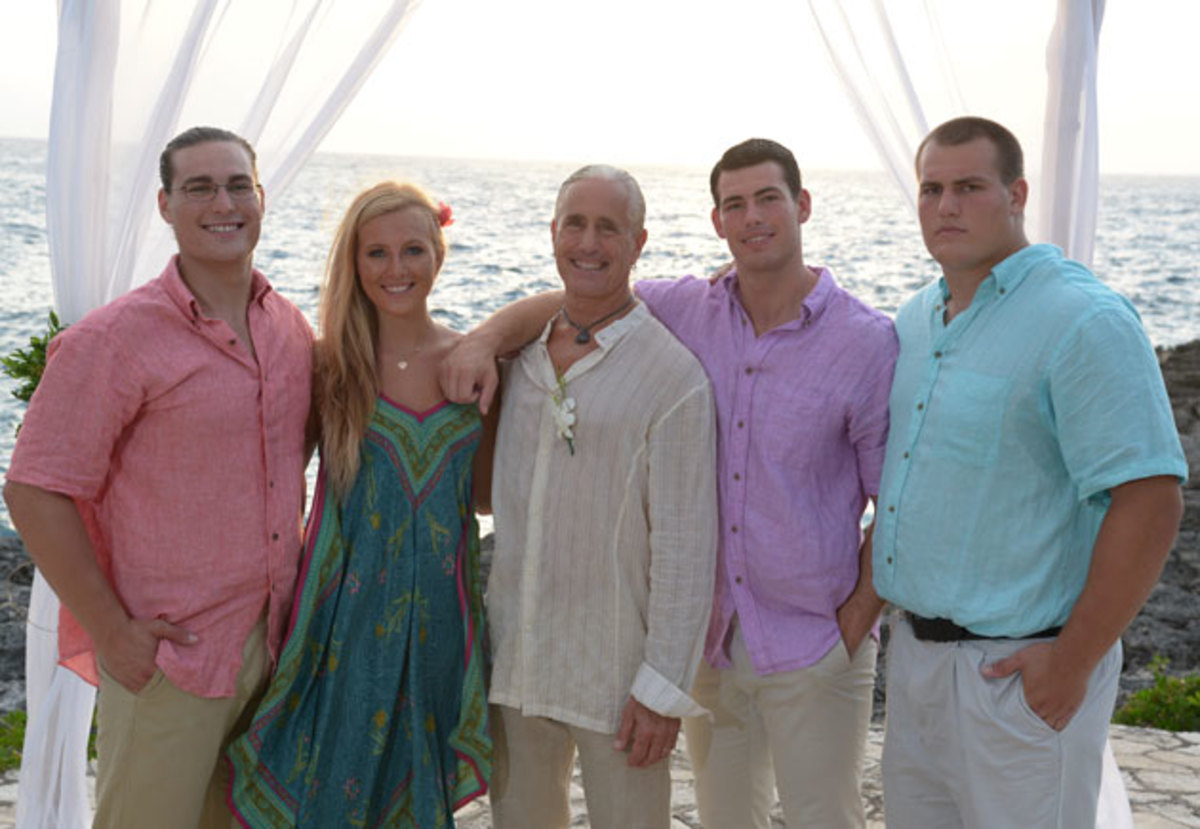

Bill and Joy hardly seem like the personalities to produce athletic children, until you meet them. Bill stands a solid six feet with strong shoulders, a sturdy handshake and admirable posture. Joy’s strong features and impressive height remain as present as they were in a music video filmed over 30 years ago. Ali was the quietest of the bunch and, ironically, the last to see sustained athletic success. Brody was the entrepreneurial, social spirit who starred in basketball and played collegiate rugby. Blaze was intellectually driven (“Mr. Facts” says Joy), but set a high school shot put record and thrived in lacrosse. Zena played sports until middle school but then cultivated a love for the medical profession. She graduates from Eckerd College this spring and then plans to apply to graduate school to become a nurse practitioner.

Bill and Joy divorced when Ali was in middle school, but both remained in Hastings and maintained joint custody of their children. They tried to hone both spirituality and celebrate other cultures when their children were young. Bill was raised Jewish, so they’d light Shabbat candles on Friday. They both enjoyed Buddhist ethics and teachings, so they’d meditate on Saturday and since Joy was raised Christian, they’d attend church services on Sunday, “thus covering all their bases,” according to Joy.

It was just one of the efforts made by Joy, who leveraged her success with the rock band Housewives on Prozac into an international festival called Mamapalooza. The festival, which is currently administrated through the New York Parks Department, celebrates families and aims to amplify the voices of women in the arts. After spending her youth in the city among artists, Joy noticed a host of women trapped in suburbia, surrendering their passions and forgetting themselves.

While her pursuit of mom rock may have occasionally embarrassed her children, she and Bill worked to maintain the family dynamic that could have easily splintered after their divorce.

“Even when I had my car covered in a big HOUSEWIVES ON PROZAC sticker in the driveway, my kids would still say “Go Mom! Go feminism! Rock on!” as they’d leave for school,” Joy says with a laugh. “I thought it was crucial to love my kids with my whole heart while caring deeply about my personal life and well-being.”

While both parents were intent on exposing their children to a host of different cultures and lifestyles, they also enjoyed athletics even if neither parent pursued them at a high level in their youth. Still, they never anticipated that Ali, whose build was strong but not overwhelming, would play collegiately, much less at the professional level.

His first interest was basketball, where he was a bulky post player with quick feet and surprising agility. Entering high school at 5'11" and 170 pounds, he didn’t envision football his primary sport.

“It was the first sport where I could compete at a very high level,” Ali says. “We were playing small local schools in football while I was able to play nationally competitive teams through AAU. Not a whole lot of it translates, but I really learned how to use my feet in the post.”

In football, Ali was generally overlooked. Division I programs didn’t look at him because they felt he was undersized—he weighed about 205 as a high school junior, about 225 as a senior and 248 after his first fall camp at Hobart—and even Patriot League teams (Bucknell, Colgate etc.) weren’t sure if he’d play offense or defense. But Hobart coach Mike Cragg and offensive coordinator Kevin DeWall noticed how seamlessly he moved along the line and how he overwhelmed defensive tackles despite his relative lack of size for the position.

“I remember Ali coming up to me after a game after the section’s top defensive end just crushed our quarterback in a high school playoff game,” Bill says. “And he told me with a laugh that it’d probably be easier to get fatter than to get faster.”

It was under the tutelage of Cragg and DeWall that Ali began making the jump that few, if any could have predicted.

The Disappearing Man: The Raider who went missing before Super Bowl

“By his sophomore season it was clear we had a special case, but I’ve been here 30 years, a head coach for 20, and the best we had was one player making it to the final roster cuts with the New York Giants,” says Cragg. “I didn’t think we’d host a Pro Day with most NFL teams showing up.”

Once Ali earned the Senior Bowl invitation, he was viewed as a project who would be exposed by the stronger competition. No longer was he in the comfortable confines of Hobart, but the nation’s premiere showcase game in Mobile, Alabama scoured by NFL scouts. Bill made the trip and was introduced to a new world.

“One agent asked me how I was enjoying Mobile. I told him that my job meant hanging around a lot of gay men and models,” Bill says. “He told me that I wasn’t in Manhattan anymore, Toto.”

The first day of practice required Ali go one-on-one with some of the nation’s foremost defensive linemen.

“I was clutching his agent’s arm so hard I thought his arm was going to break,” Bill says. “Here he is going up against these big m-----f----- from the SEC and he’s just going to get creamed!

“Then when I saw that first one-on-one, I said ‘Wow’ … maybe he does have it.”

“In the game, he looked like a top prospect from Ohio State,” Licht says.

The Buccaneers joined a host of other teams at bucolic Hobart for the school’s first-ever pro day to run him through drills. The Bills even worked him out at tight end for an hour. “The Bills guys are asking me how good his hands are,” Cragg says. “I said how the hell should I know? He’s my left tackle.”

As draft day inched closer, the relative unknown from Hobart was now plastered all over ESPN and the NFL Network as the draft’s most unique revelation. The only question left was who would select him.

***

When the draft arrived, Licht and the Bucs knew they’d be selecting Florida State’s Jameis Winston, who they considered the draft’s best pro-style quarterback, with the first pick. After that, they tabbed Penn State’s Donovan Smith at No. 34, who they envisioned as their left tackle of the future. Licht wanted another offensive lineman, preferably a guard, but was wary of waiting until pick No. 65.

“I was taught that if you want something in this business, you need to go and get it,” Licht says. He traded up four slots from No. 65 to No. 61 to pass up both Seattle and New England, both rumored to be considering Ali. When commissioner Roger Goodell stepped to the podium to announce the pick, Ali was already celebrating with family and friends. His agent informed him that he would head to Tampa Bay.

Roundtable: What will media coverage of Super Bowl look like in 50 years?

Virtually unknown before the beginning of 2015, Ali became the highest Division III player ever selected in the NFL draft. Five months later, he’d start at left guard for the Buccaneers, an unprecedented ascent for a player of his pedigree. Some Division III players reach the NFL at skill positions (Washington’s Pierre Garçon and Houston’s Cecil Shorts are two examples), but seldom appear in the trench positions. The physical demands and adjustments are usually too overwhelming.

“He went up with Gerald McCoy (Tampa Bay’s all-pro defensive tackle) in training camp and we kept saying all throughout training camp that Gerald is going to make this guy better,” Licht says. “And Gerald did make him better, but about the third week of camp we kind of looked at each other and thought ‘maybe Ali is making Gerald better too.’”

Pro Football Focus has graded him as one of the best run-blocking offensive linemen in multiple weeks, even after he missed three games with a high ankle sprain. They also ranked him the best at pass blocking efficiency of any rookie guard. When asked about the tandem of Winston, Smith and Marpet, Buccaneers offensive coordinator Dirk Koetter said “we hit the jackpot there.”

With the unshakeable confidence of a mother, Joy doesn’t express much surprise about her son’s success. “Ali is a seriously competitive guy and a deep and powerful thinker,” she says. “He’s committed and contemplates things very rigorously. He was just born that way.”

Shortly after concluding a conversation about the core tenants of maternal theory and showing me a 1,500-page book with its most important readings, Joy asks if I saw the Bucs’ game-winning drive against the Falcons in Week 13. I nod.

“First Jameis’s scramble and then scoring with a minute and a half left?!” Joy chirps. She gives me a high-five as if the play just happened. “Sometimes I wish feminism were more like football,” she says. “At least on that field there’s less room for interpretation and more of a focus on competition.”

As she discusses the "universal bond" tenant of Mother Studies, I consider Licht’s emphasis on the importance of the draft and fostering a familial unit. Perhaps this is where feminism and NFL draft strategy coalesce.

Without a familial bond, success is more difficult to achieve.Licht seeks a family, Joy wants to educate the world about its importance. Licht is trying to instill a connected unit in Tampa Bay, and one of his key pieces for the future is formerly one of the little guys, his starting guard from Hobart, Ali Marpet.