Tom Brady faces long odds after NFL wins Deflategate appeal

Get all of Michael McCann’s columns as soon as they’re published. Download the new Sports Illustrated app (iOS or Android) and personalize your experience by following your favorite teams and SI writers.

Tom Brady is legendary for late-game heroics with the odds stacked against him. He better hope his attorneys have that same skill set.

On Monday, two of three federal judges assigned to hear the NFL’s appeal of U.S. District Judge Richard Berman’s ruling in favor of Brady ruled to reverse Judge Berman’s decision. Barring a successful new appeal, petition for a stay or a negotiated settlement between the NFL and NFLPA, Brady will sit out the first four games of the 2016 regular season due to his alleged conduct in the Deflategate controversy.

• KING, BRANDT: Two views on the NFL’s successful appeal

Why the NFL won the appeal

The simplest answer is that Judges Barrington Parker, Jr. and Denny Chin reasoned that NFL commissioner Roger Goodell enjoyed sweeping authority while acting as an arbitrator in Brady’s appeal of a four-game suspension, and that he acted within the far-reaching boundaries of this authority. Federal courts can only disturb arbitration awards in extraordinary circumstances, and two of the three judges did not find that those circumstances existed for Brady. The two judges also stressed how the collective bargaining agreement between the NFLPA and NFL fails to contractually stipulate the procedural safeguards that Brady and the NFLPA believe ought to exist. To be clear, they did not rule that Brady knew or played a role in a plot to deflate footballs or even that such an act took place. They only ruled that Goodell was legally authorized to reach these conclusions.

Despite new Deflategate win over Tom Brady, Roger Goodell remains a loser

Writing for both himself and Judge Chin, Judge Parker’s 33-page opinion consistently stressed that federal courts can review arbitration awards in a very narrow manner and also must maintain a “highly deferential” style of review towards the arbitrator. “Even if an arbitrator makes mistakes of fact or law,” Judge Parker wrote, “we may not disturb an award so long as he acted within the bounds of his bargained-for authority.” Further, Judge Parker reasoned, Goodell only needed to avoid ignoring the plain language of the CBA—which, especially in Article 46, provides Goodell with widespread power—in order to meet this very low bar.

Adopting this very deferential review of Goodell’s authority in the context of a CBA that is itself deferential to Goodell, Judge Parker found the commissioner’s various reasons for upholding Brady’s four-game suspension to be sufficiently logical. For instance, Judge Parker was “not troubled” by Goodell comparing Brady’s possible awareness or involvement in an alleged ball deflation plot to a steroids user since Article 46 of the CBA affords Goodell “generous latitude” in his reasoning. Further, Judge Parker noted, Brady was not contractually “entitled” under Article 46 “to advance notice of the analogies the arbitrator might find persuasive.”

Judge Parker also found it reasonable for Goodell to determine that Brady’s conduct “was more serious than was initially believed,” since—again—the CBA does not bar Goodell from adopting a different viewpoint after hearing Brady’s testimony in his appeal. Along those lines, Judge Parker reasoned, no rule prevents Goodell from making negative assumptions from Brady’s “non-cooperation” (the destruction of his cell phone), particularly since no rule bars Goodell from imposing suspensions for violations of equipment policy.

Judge Parker was also skeptical of Brady and the NFLPA being able to pose questions to NFL general counsel Jeffrey Pash, who was originally tapped by Goodell to be co-lead investigator with Ted Wells. Pash reviewed and presumably edited the Wells Report prior to its release, a development that cast serious doubt on whether Wells was—as Goodell claimed—“independent.” Judge Parker found Wells’s independence and Pash’s role as reviewer and editor to be irrelevant points under the law: “The CBA does not require an independent investigation, and nothing would have prohibited the Commissioner from using an in-house team to conduct the investigation.” Without a CBA rule that requires Pash to testify, Goodell was determined to be within his authority to quash an opportunity for NFLPA attorneys to question Pash.

A timeline of the Deflategate controversy

Similarly, Judge Parker found the CBA to contain no language that required the NFL to turn over investigative notes. The judge also believed the absence of language in the CBA meant there was no need to remand the case back to Judge Berman. As discussed in prior SI.com articles, Judge Berman had explicitly reserved for further review three issues: (1) whether Goodell engaged in an “evidently partial” manner by delegating authority to NFL executive vice president Troy Vincent; (2) whether Goodell violated the law by drawing conclusions from materials other than the Wells Report and Brady’s appeal; and (3) whether Goodell publicly making positive remarks about the Wells Report made it impossible for Brady to obtain a fair appeal.

Time and time again, Judge Parker essentially reasoned that in the absence of a procedural right obtained by the NFLPA in the CBA, he and Judge Chin were unwilling to create one. Perhaps the NFLPA will more aggressively seek such procedural rights in the next CBA.

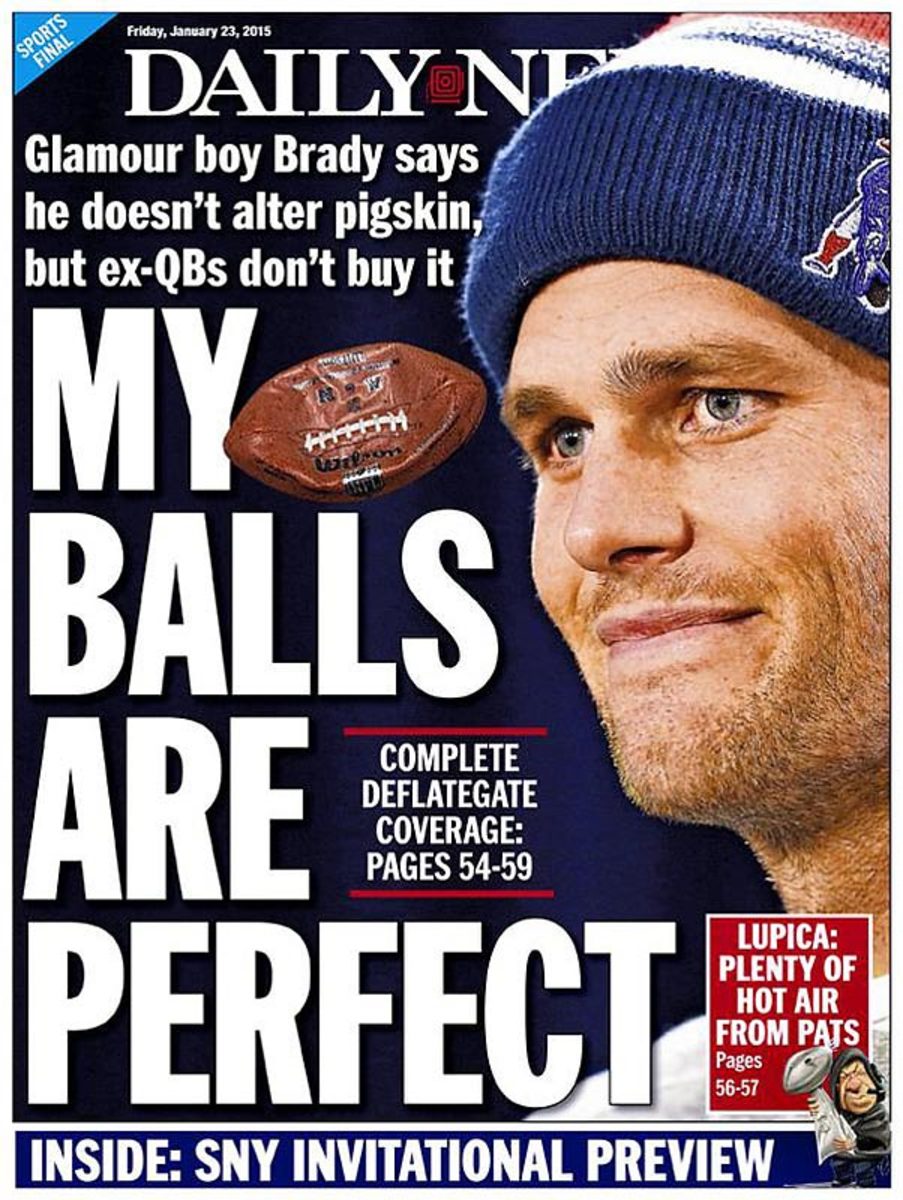

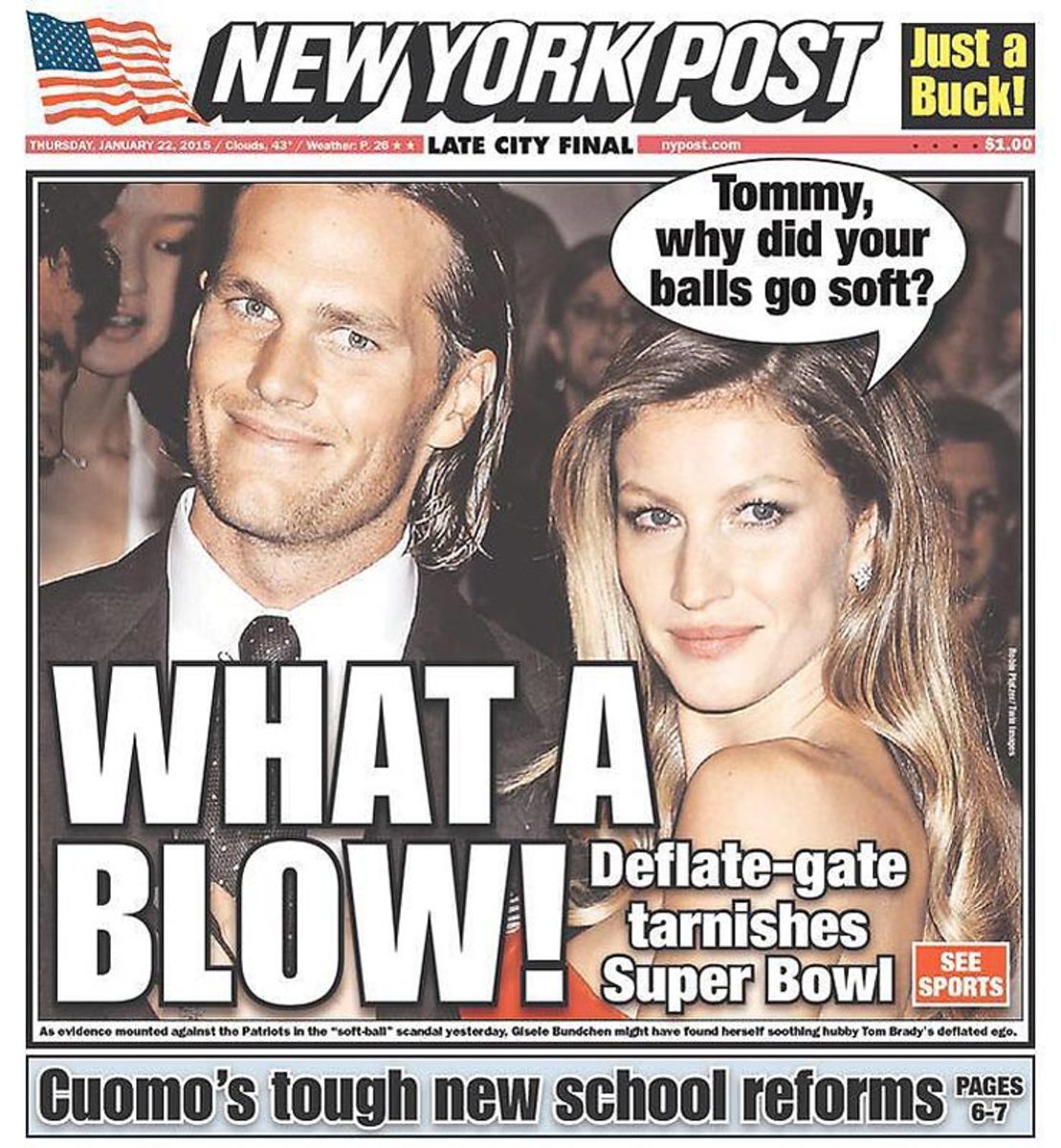

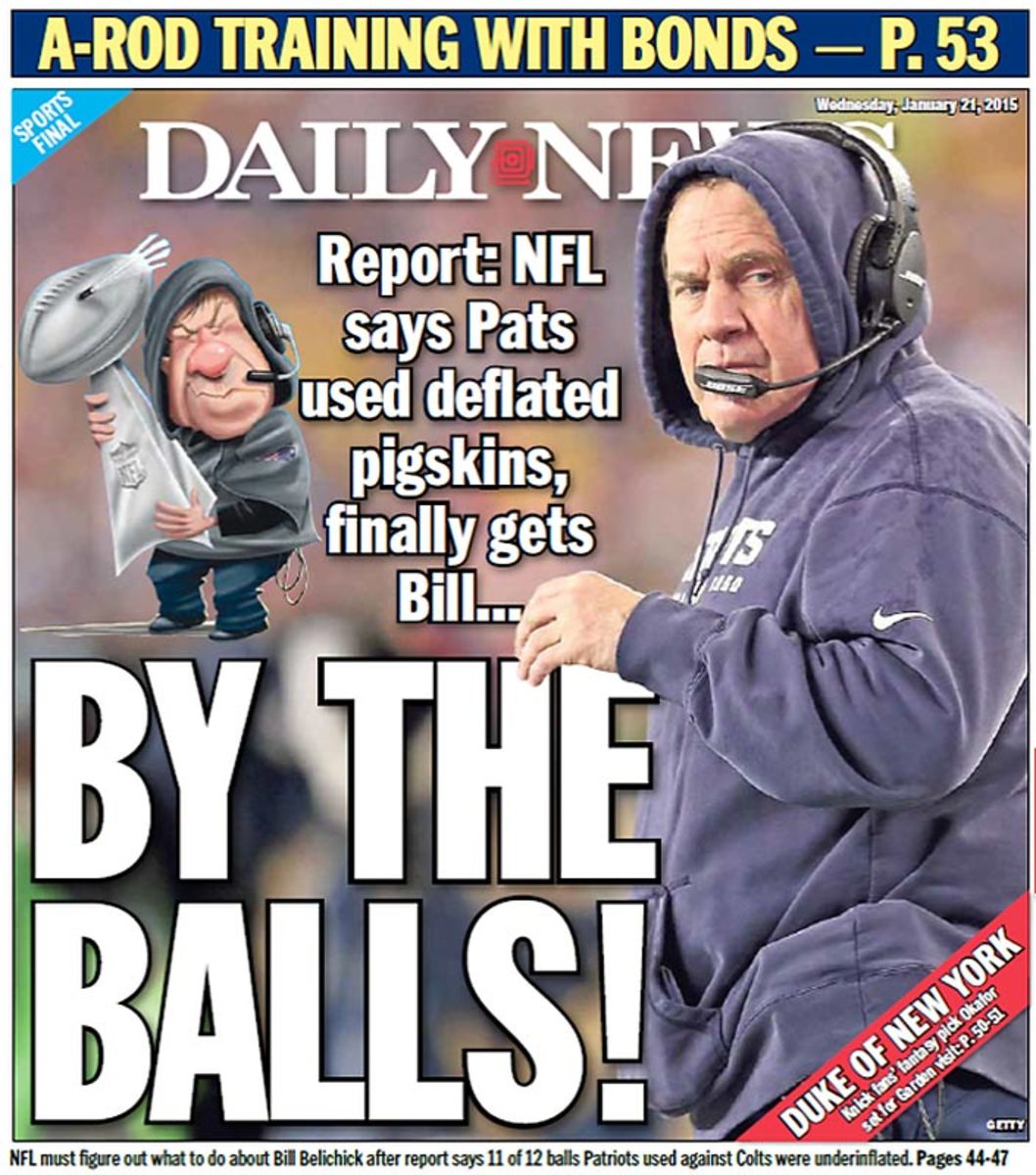

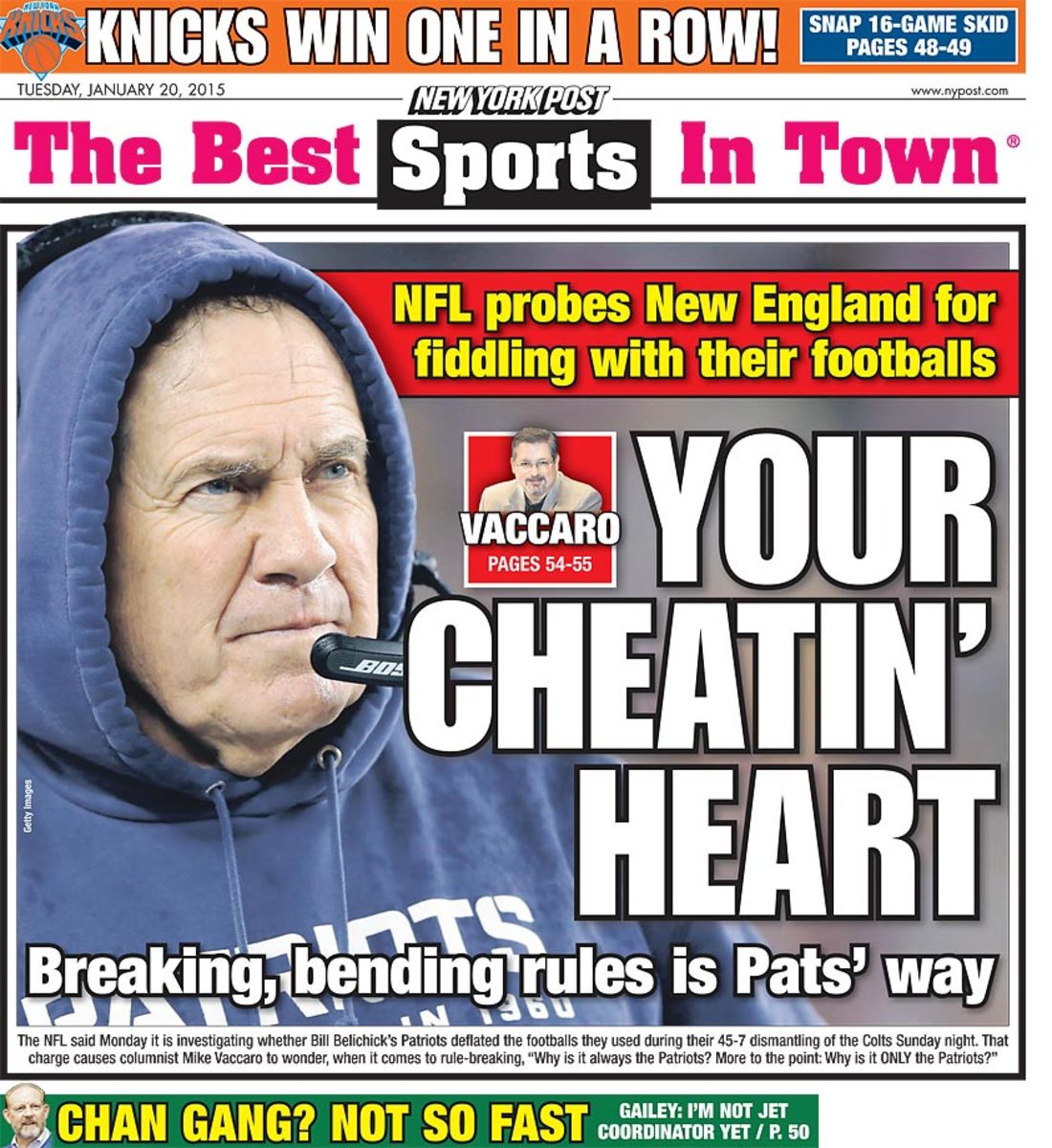

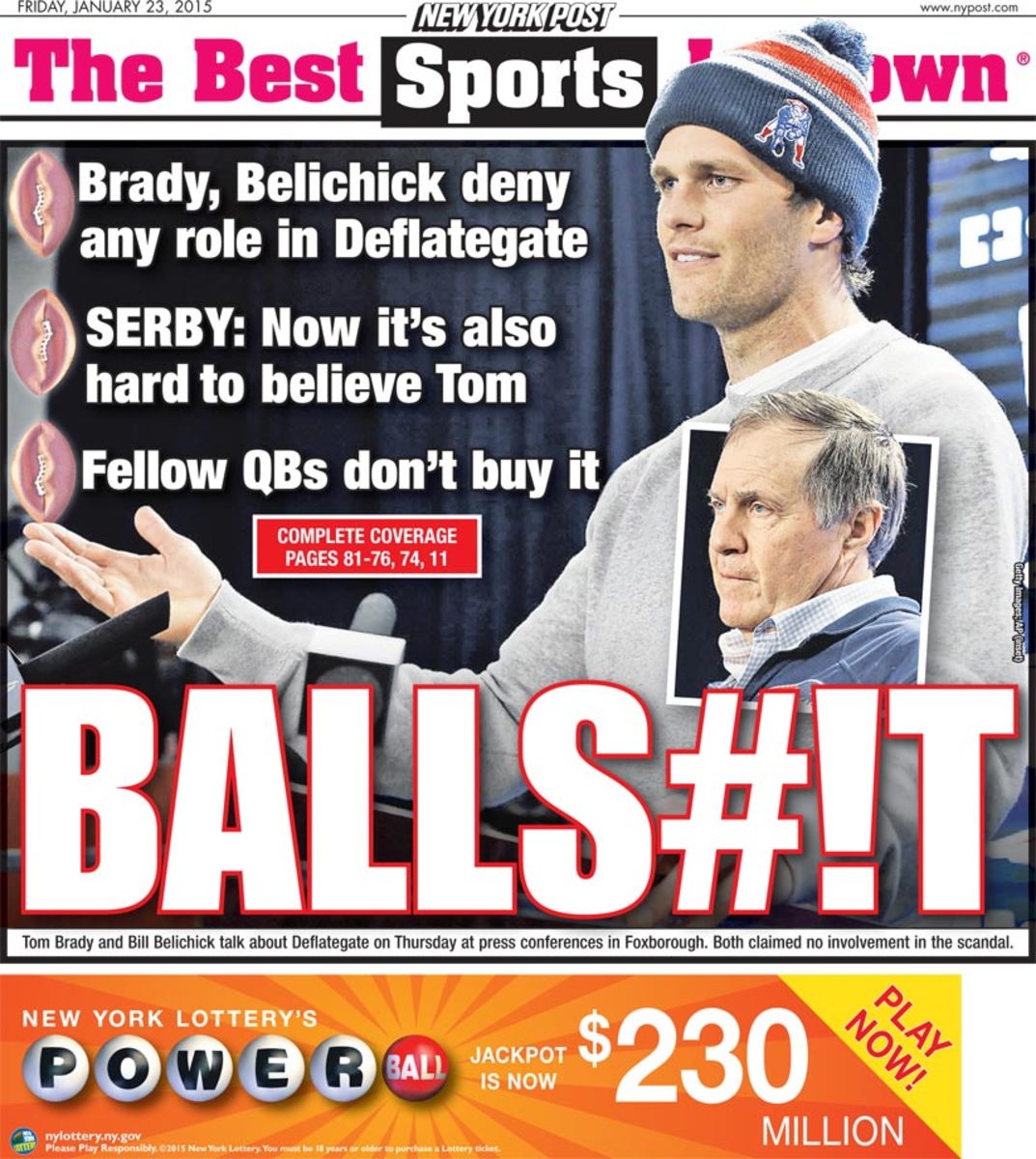

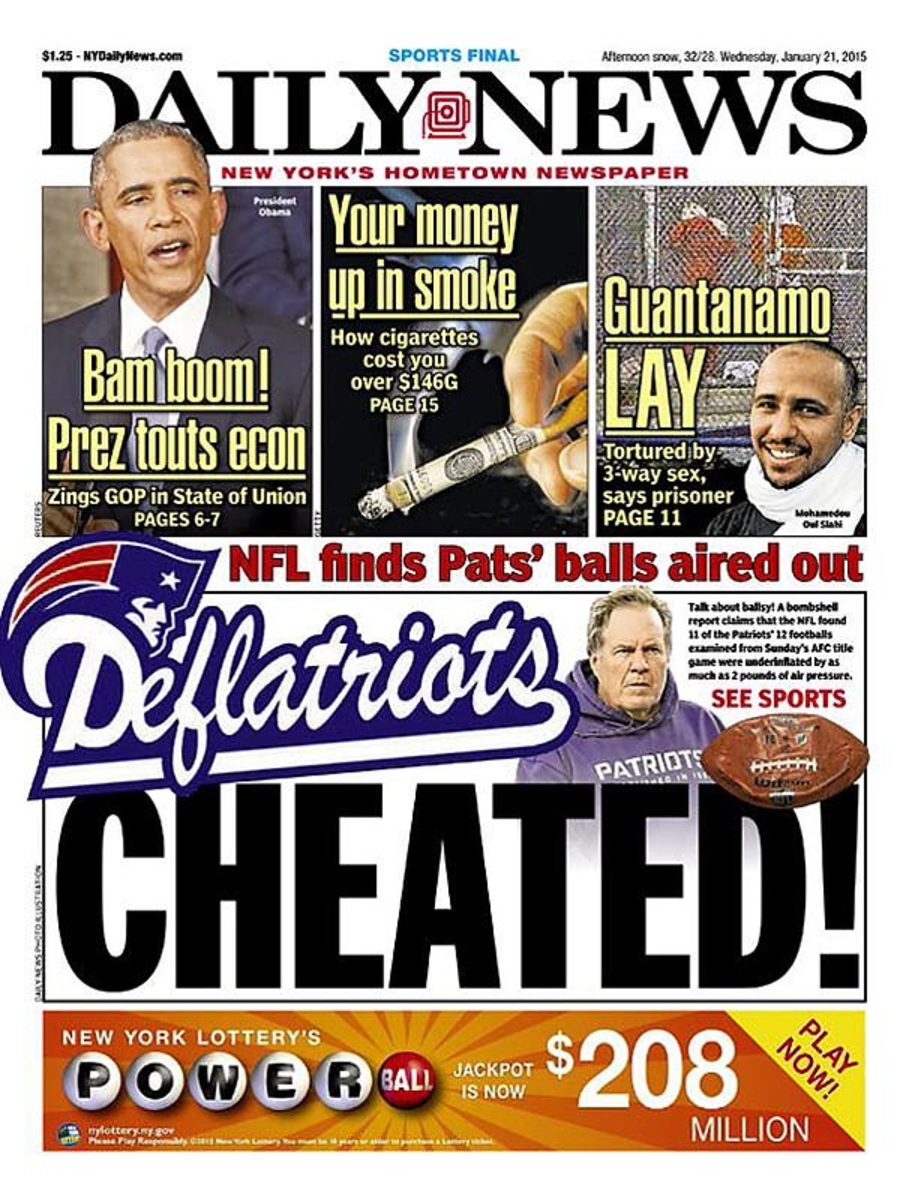

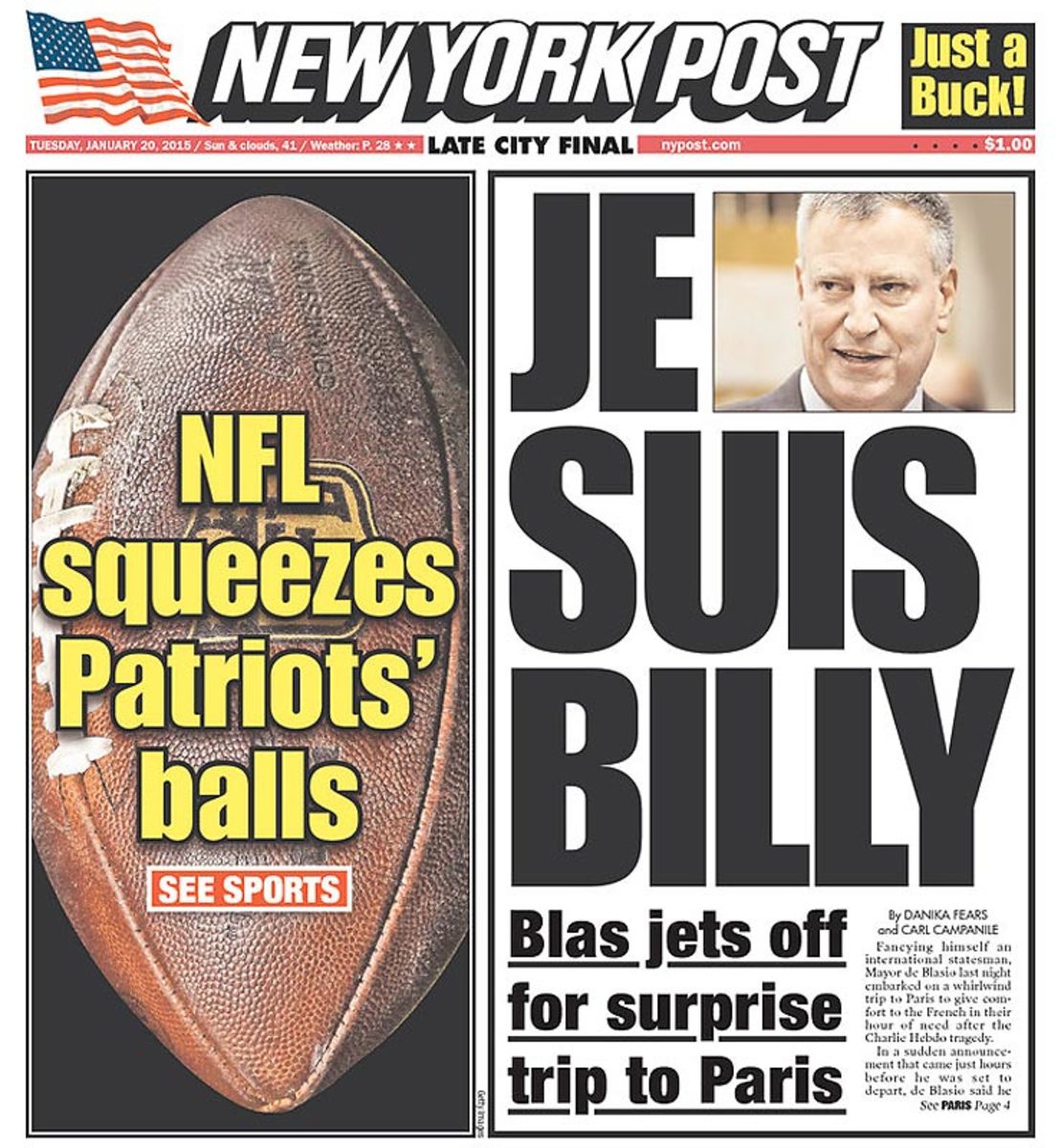

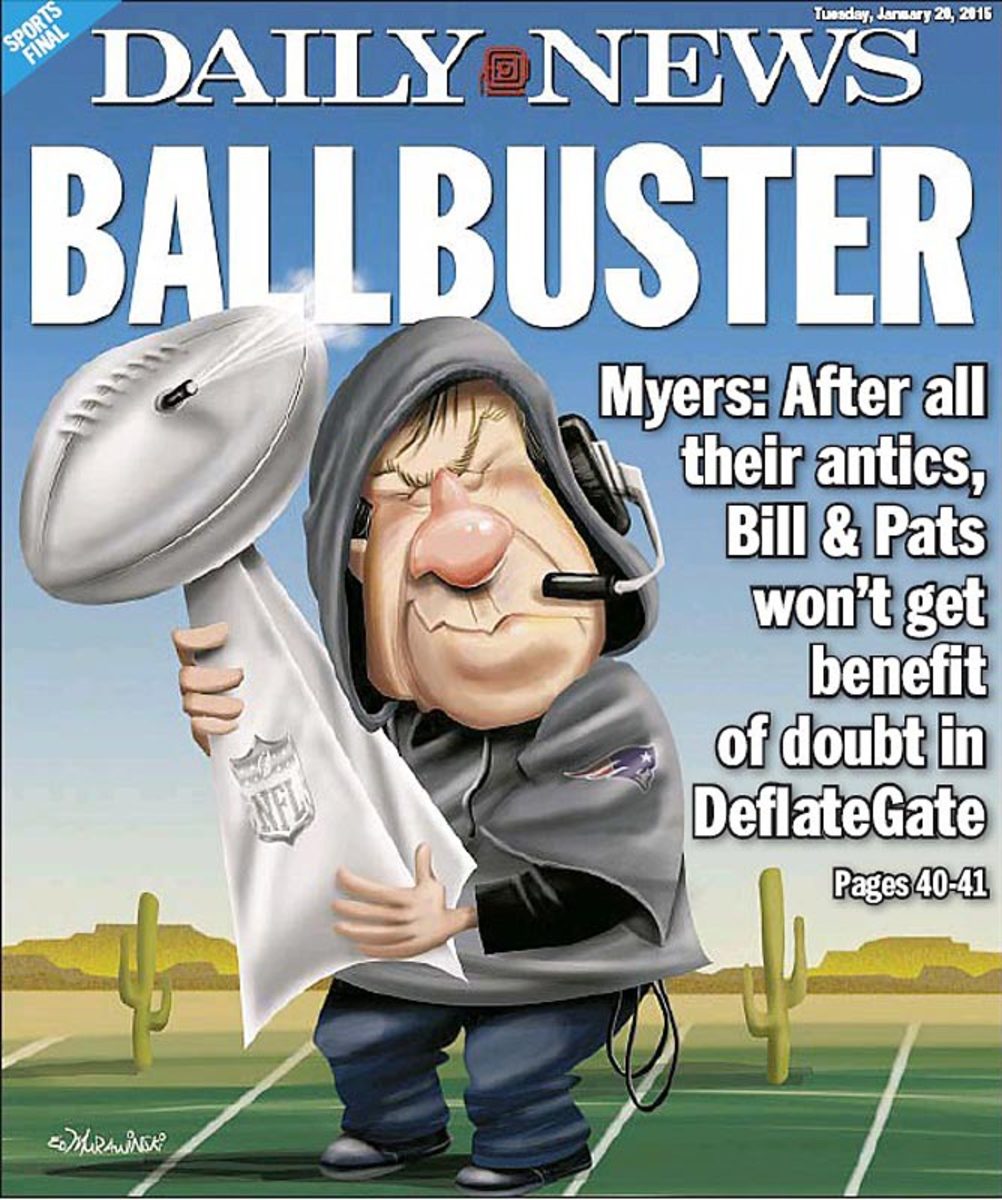

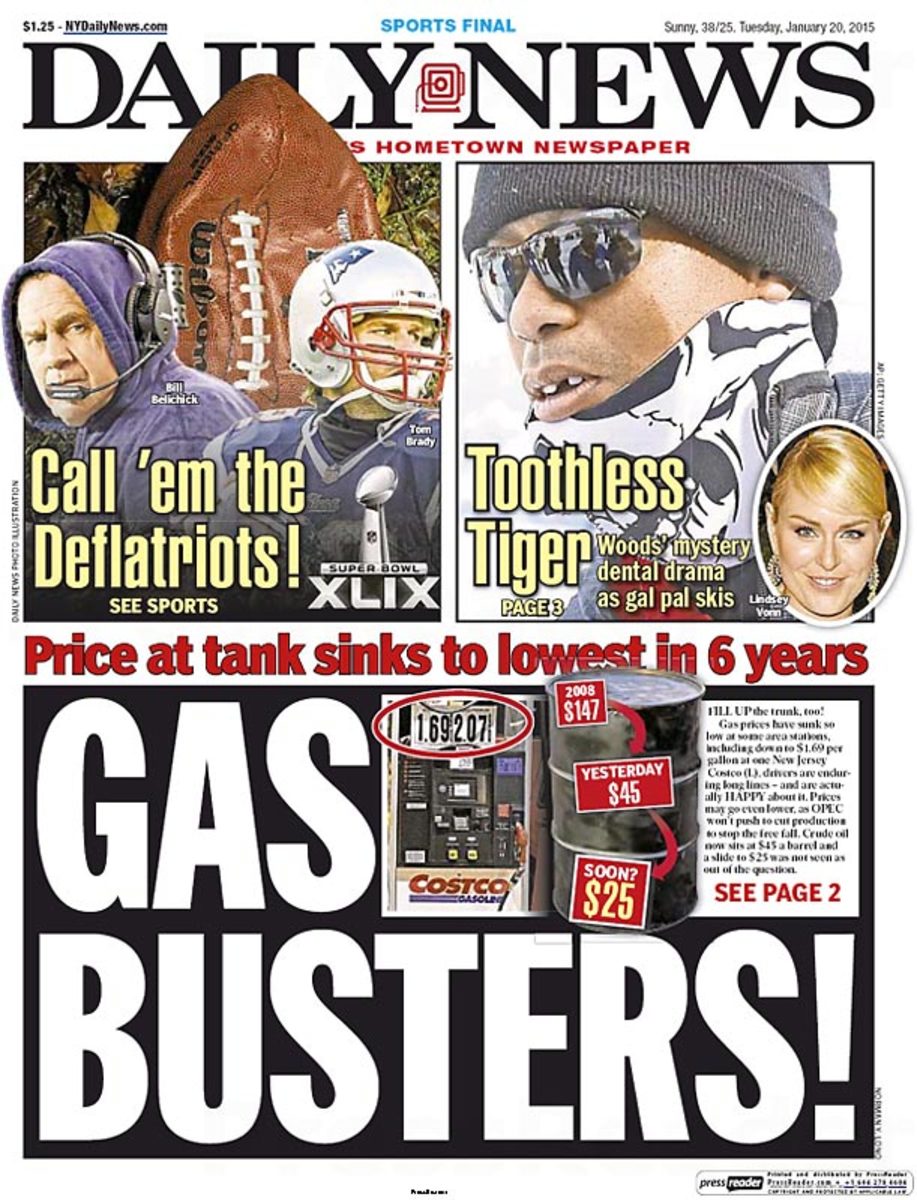

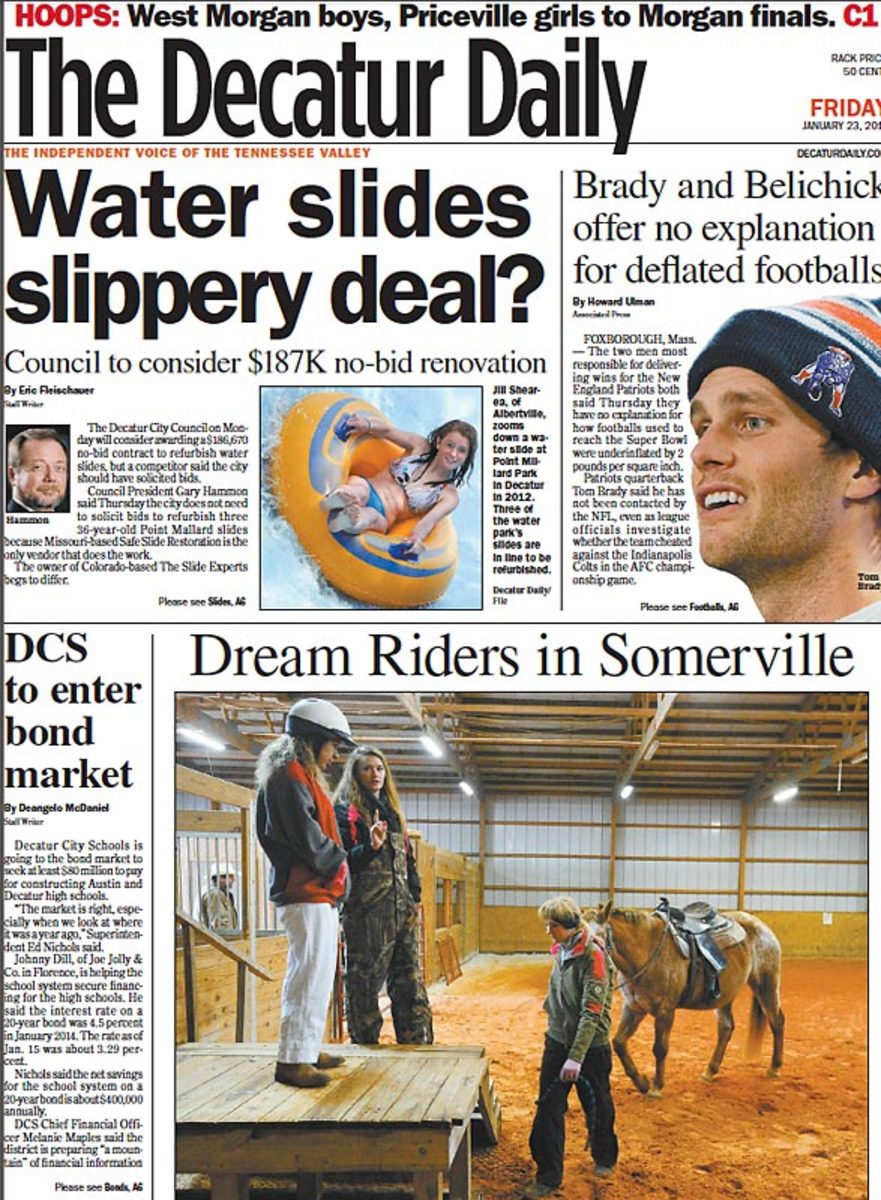

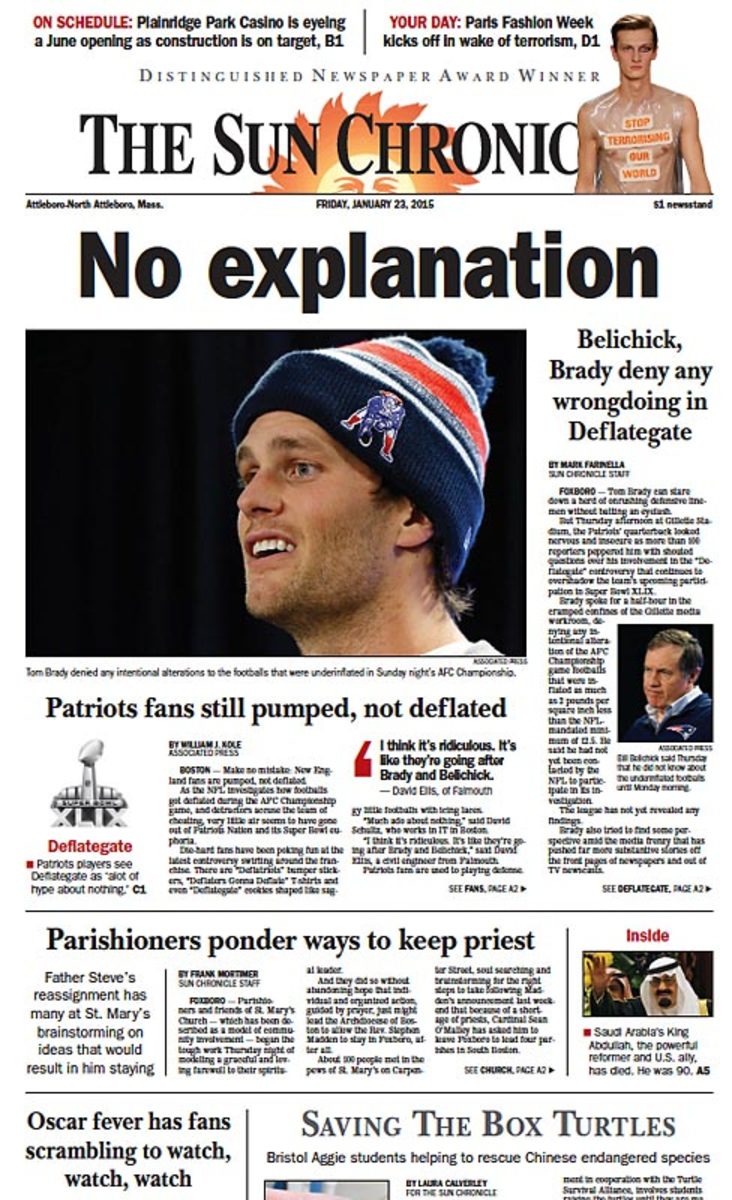

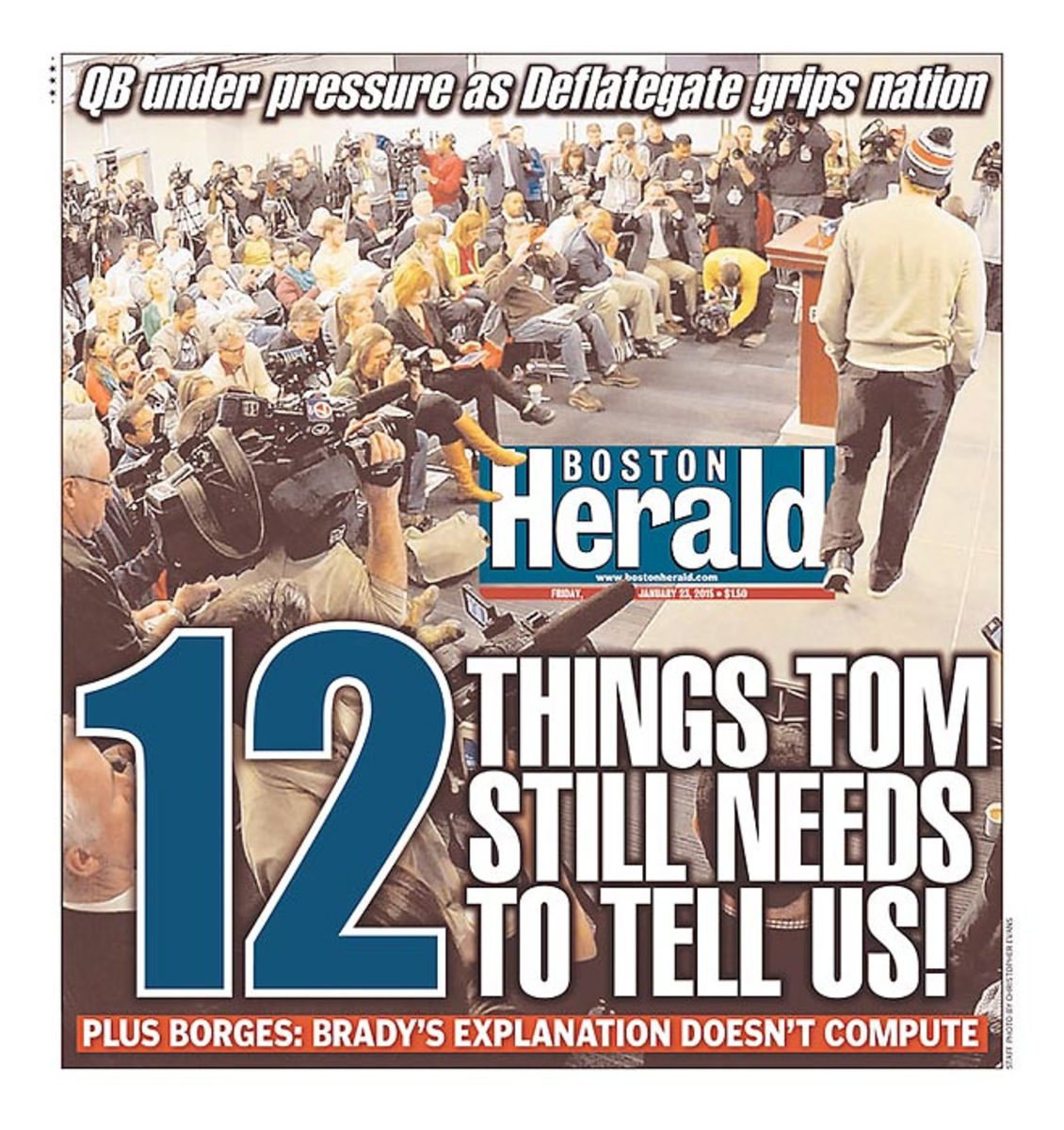

Gallery: Newspaper headlines from the Deflategate saga

Deflategate Newspaper Headlines

Brady’s remaining options and their relationship to the dissenting opinion

It’s not over for Brady, but his legal team faces very long odds. First, the NFLPA has 14 days to petition the three-judge panel for a rehearing. Unfortunately for Brady, this petition will almost certainly be rejected, since two of the three judges just ruled decisively against Brady.

Second, the NFLPA can petition for a rehearing en banc, in which all 13 of the active judges on the Second Circuit court of appeals plus Judge Parker (who is a senior status judge but eligible under court rules to participate in a rehearing because he was on the three-judge panel) would hear a new appeal. The 13 active judges would be eligible to vote on whether to grant a rehearing en banc. A decision on whether to grant a rehearing en banc would likely be issued long before the 2016 regular kicks off in September, but if not, Brady’s suspension would be stayed (postponed) until that vote occurs. If a majority of the 13 judges agree to grant a rehearing, the rehearing would be heard months from that point. Presumably, Brady’s pending suspension would be postponed until an accompanying ruling, which would most likely be issued in 2017.

Brady’s odds for obtaining a rehearing en banc are not good. Available data indicates the Second Circuit grants rehearings en banc less than 1% of the time. But the odds might be higher for Brady since the decision was split 2–1, and since it was the Second Circuit’s Chief Judge, Robert Katzmann, who dissented in Brady’s favor. It’s possible other judges on the Second Circuit will accord extra deference to the chief judge and perhaps find his reasoning to be persuasive.

In his nine-page dissent, Judge Katzmann expressed being “troubled” by Goodell’s conduct as the arbitrator. Judge Katzmann stressed that the four-game suspension was “unprecedented” and he chided Goodell for adopting a “shifting rationale for Brady’s discipline.” Like Judge Berman, Judge Katzman found that Goodell’s decision embodied “his own brand of industrial justice.”

In building his dissenting opinion, Judge Katzmann reasoned that Goodell clearly violated the law in basing his decision “on misconduct different from that originally charged.” Judge Katzmann highlighted how Brady was initially accused by Goodell of being “generally aware” of Jim McNally and John Jastremski allegedly deflating footballs, whereas Goodell—for reasons that were never made clear—later reasoned that Brady was something of a conspiratorial ring leader whereby he “knew about, approved of, consented to, and provided inducements.” Judge Katzmann found this change to be material and grounds for vacating the suspension.

Judge Katzmann also found the NFL’s portrayal of Brady’s alleged gift-giving to McNally and Jastremski to be prejudicial to Brady. As Judge Katzmann writes, Brady did not know prior to the appeal that Goodell would make Brady’s alleged gifts to locker room attendants a central part of his analysis. “Had the Commissioner confined himself to the misconduct originally charged,” Judge Katzmann writes, “he may have been persuaded to decrease the punishment initially handed down.”

Media Circus: How ESPN and NFL Network will cover NFL draft

Judge Katzmann also took issue with Goodell failing to mention, let alone explain, “a highly analogous penalty”: the fact that the league has only punished players who are caught using stickum on their gloves with fines. Judge Katzmann was particularly bothered by the fact that Goodell would inexplicably omit any reference to stickum penalties when, “the League’s justification for prohibiting stickum—that it ‘affects the integrity of the competition and can give a team an unfair advantage,’ —is nearly identical to the Commissioner’s explanation for what he found problematic about the deflation—that it ‘reflects an improper effort to secure a competitive advantage in, and threatens the integrity of, the game.’ ”

Brady and NFLPA attorneys Jeffrey Kessler and David Greenspan must hope that other judges on the Second Circuit concur with Judge Katzmann’s points. If, however, Brady fails to obtain a rehearing or a rehearing en banc, he would likely petition for a stay of his suspension while he appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court. As I wrote earlier in this process, a stay reflects a court order preventing the NFL from carrying out its punishment—a four-game suspension—until the appeals process is complete. Brady would argue that he would suffer irreparable harm in the absence of a stay. He would insist that once he serves a four-game suspension, he could never play those games again. For all practical purposes, Brady’s case becomes moot once he serves the suspension.

It is very unlikely the Supreme Court would review this case. The Court normally reviews only about 1% of petitions, and the cases the Court selects tend to be of paramount importance—not whether a football player sits out four games due to the extremely unusual system of dispute resolution. The justices will likely reason that the Brady case is too fact-specific, involving a scenario unlikely to arise in other labor-management disputes.

That said, Brady could benefit if the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eight Circuit were to rule in favor of Adrian Peterson. A decision in the Peterson case is expected any day now. In February 2015, U.S. District Judge David Doty ruled in favor of Peterson, who was punished under a new domestic violence policy for conduct that took place during a previous policy. If the Eighth Circuit affirms Judge Doty’s ruling in the face of the NFL’s appeal, it could present a conflict between the Eighth Circuit and the Second Circuit on how the NFL interprets Article 46 in resolving disciplinary matters and more specifically how issues of notice and consistency are evaluated. So-called “circuit splits” increase the likelihood that the Supreme Court will agree to hear a case. While the Brady and Peterson cases are different in many ways, Peterson winning would clearly be good news for Brady’s team if it were to seek review by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Brady and the NFL could still reach a settlement, but don’t count on it

It is also possible that the NFL and NFLPA could negotiate an end to the case through a settlement. A settlement might call for a reduced suspension—say, two games. In return, the NFLPA and Brady would agree to drop any subsequent court appeals. Both sides would gain closure, with the NFL maintaining its “win” against Brady and Brady obtaining a reduced punishment. The New England Patriots might find such an outcome appealing given that Brady would only miss Week 1 (against the Cardinals) and Week 2 (against the Dolphins) and would return for Week 3 (against the Texans). During Brady’s absence, Jimmy Garoppolo would presumably start at quarterback.

• From the SI Vault: Why the Patriots trust backup QB Jimmy Garoppolo

I have a hard time seeing Brady agreeing to any settlement. If he accepts a settlement, his critics would insist he is a “cheater” (even though no court has ruled on what Brady did or didn’t do—the courts have only ruled on whether Goodell was acting within his legal authority to suspend Brady). At age 38, Brady is surely appreciative of how he will be remembered when his playing days are over. He might be better off maintaining his innocence, even if that probably means sitting out four games.

Brady could still file a defamation lawsuit

Under Massachusetts law, Brady has three years from the date of alleged defamatory statements to file a defamation lawsuit against the NFL and Goodell. While a successful defamation lawsuit would only lead to monetary damages awarded to Brady—who is reportedly worth in the ballpark of $130 million—and would have no impact on whether the NFL can suspend him, Brady could (as suggested by MIT professor John Leonard) donate any monetary damages awarded to charity. Brady may see a successful defamation lawsuit as a way to restore his image and perhaps get the “last laugh” against the NFL.

Nevertheless, defamation lawsuit is unlikely. As a public figure, Brady face a higher legal bar in a defamation lawsuit than would an ordinary person. He would need to show “actual malice,” meaning the league intentionally or knowingly made untrue and damaging statements about him. This is often a high bar. The NFL would also argue, as it argued in Jonathan Vilma’s defamation lawsuit against Goodell over Bountygate, that a defamation lawsuit is “preempted” by the CBA’s language expressing that player-league disputes must be resolved through internal league procedures and that players thus cannot obtain alternative relief through courts. A federal judge agreed with the NFL about preemption in the Vilma case and it’s possible the same result could occur for Brady.

In sum, while the odds are decisively stacked against Brady’s in prevailing in Deflategate litigation, they are not insurmountable. We await his next move.

Michael McCann is a legal analyst and writer for Sports Illustrated. He is also a Massachusetts attorney and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire School of Law. He also created and teaches the Deflategate undergraduate course at UNH, serves as the distinguished visiting Hall of Fame Professor of Law at Mississippi College School of Law and is on the faculty of the Oregon Law Summer Sports Institute.