Why Tom Brady walked away from Deflategate, and what might be next

One of history’s most newsworthy sports legal controversies likely ended on Friday. Patriots quarterback Tom Brady announced on Facebook that he will not continue his federal appeal against the NFL over his four-game suspension. Put bluntly, Deflategate is likely dead.

Brady’s litigation has centered on whether NFL commissioner Roger Goodell lawfully upheld Brady’s suspension pursuant to Article 46 of the collective bargaining agreement. Four federal judges—Richard Berman, Robert Katzmann, Barrington Parker, Jr. and Denny Chin—heard oral arguments over the case. Two ruled for Brady and two for the NFL. But three of those judges are federal appeals judges, rather than district court judges like Judge Berman, and two of those federal appeals judges—Judges Parker and Chin—ruled for the NFL. Brady thus lost 2–1 at the highest judicial level that has reviewed his case.

Further, Brady was unable to convince other judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit to reconsider his arguments. On Wednesday, the Second Circuit’s 13 active judges denied Brady’s petition for a rehearing, thereby leaving the three-time Super Bowl MVP with only one option: take his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. It was an option that Brady decided to turn down.

• A complete timeline of Deflategate, from scandal to suspension to circus

Why Brady walked away from the case

Brady’s decision is both surprising and unsurprising.

Brady has steadfastly maintained his innocence from the very beginning. He even gave sworn testimony—thereby risking potential perjury criminal charges—in which he categorically rejected the NFL’s accusations that he had knowledge of a scheme to illegally take the air out of the Patriots’ footballs, a plot that many scientists believe did not occur and in fact is incompatible with the basic laws of physics. To be sure, Brady’s litigation has centered not on whether Brady did anything, but on the appropriate boundaries of how an arbitrator interprets a collectively bargained provision. Nonetheless, it has served as a public vehicle for Brady to challenge the NFL’s assertions and potentially win over skeptics. Brady now walks away from all of that.

The decision is also surprising in that Brady had retained one of the best legal teams ever assembled, and his lawyers were surely ready to petition the Supreme Court. In particular, Brady’s hiring of former U.S. Solicitor General Ted Olson, who has argued numerous times before the Supreme Court, hinted at his desire to exhaust every option. There is no doubt Olson was ready to take the case to the Supreme Court. If he does so, it will only be on behalf of the NFLPA and not Brady.

But Brady’s decision is less surprising when considering other important factors. For starters, a petition to the Supreme Court faced very long odds. Brady would have been asking U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to grant a stay on his suspension that, as I explained more fully on Wednesday, would have prevented the NFL from holding Brady out of action until the other justices had considered Brady’s petition. As a practical matter, a stay would have likely enabled Brady to play in Week 1 against the Cardinals and possibly throughout the 2016 season—depending on when the other justices considered his petition.

Odds matter, however, for any litigant. Not only was Justice Ginsburg unlikely to grant a stay, but even if she did grant one, the other justices were poised to reject Brady’s writ of certiorari sometime in the fall. Keep in mind, the Supreme Court only accepts about 1% of writs—Justice Ginsburg granting a stay by no means ensured Brady would get a full hearing.

If the Supreme Court had rejected Brady’s petition after being granted a stay, the NFL would immediately enforce its suspension of Brady, and perhaps that moment would have occurred at a point in the season particularly detrimental to the Patriots. While Patriots coach Bill Belichick now has weeks to prepare Jimmy Garoppolo to start in Brady’s absence in Weeks 1 through 4, he would have at most days to prepare Garoppolo had the Supreme Court rejected Brady’s petition in the middle of the season.

Brady’s decision is also understandable because, frankly, he is probably tired of the litigation. I am sure he wants to return his focus to football. Patriots training camp opens on July 27, and preseason games will soon follow. While Brady would not have had to appear in any forthcoming court hearings, he would have been kept updated on the case by his attorneys. And no doubt, journalists would have kept asking him about the case.

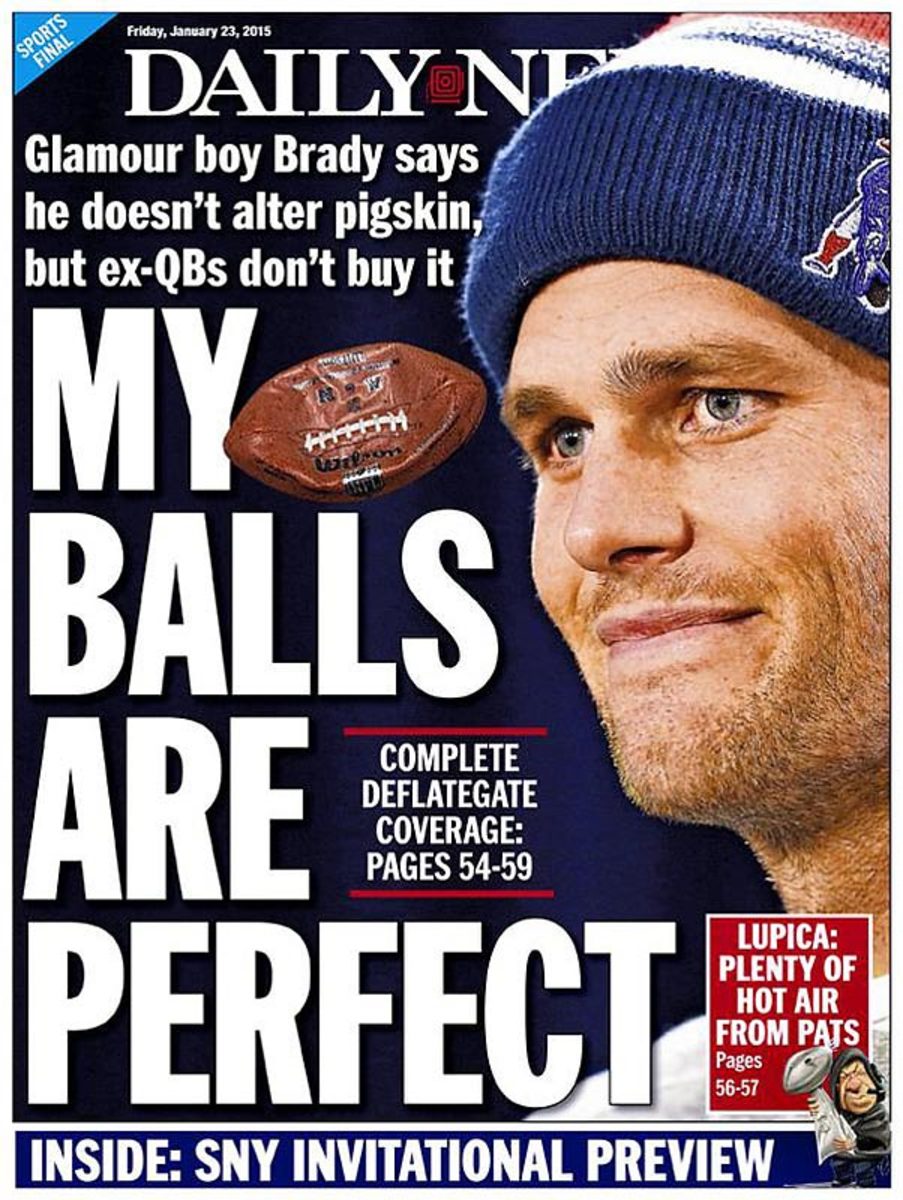

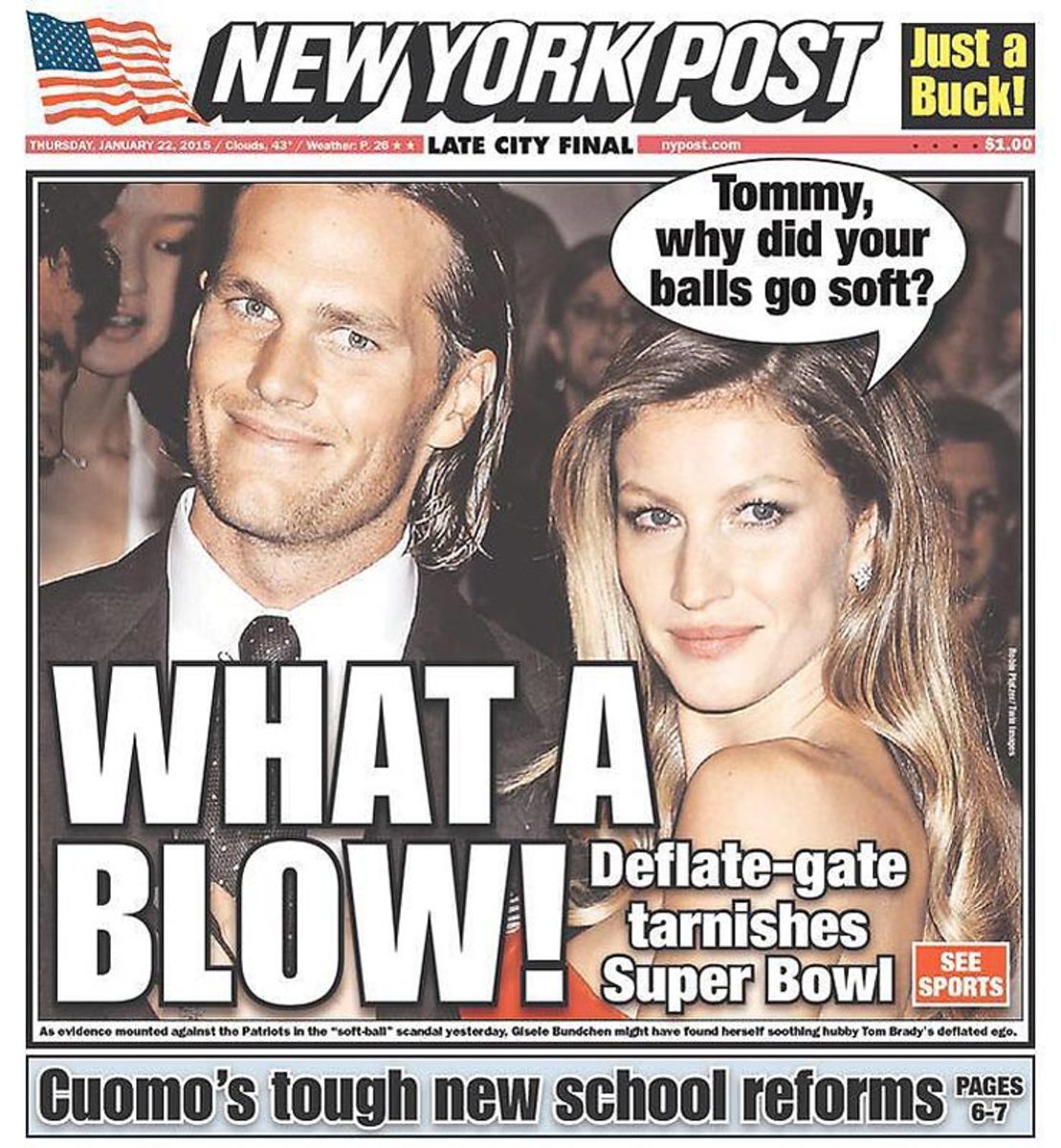

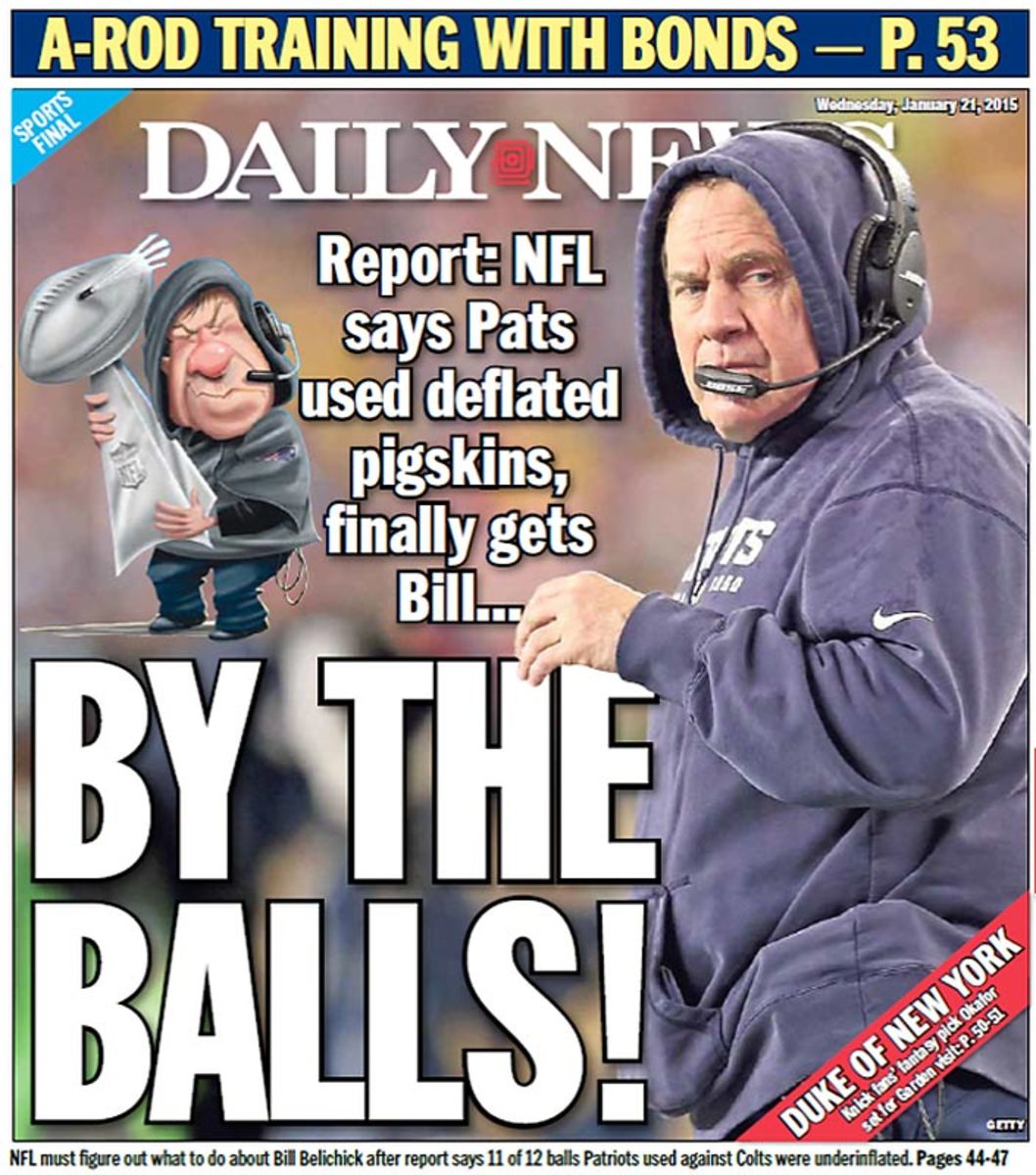

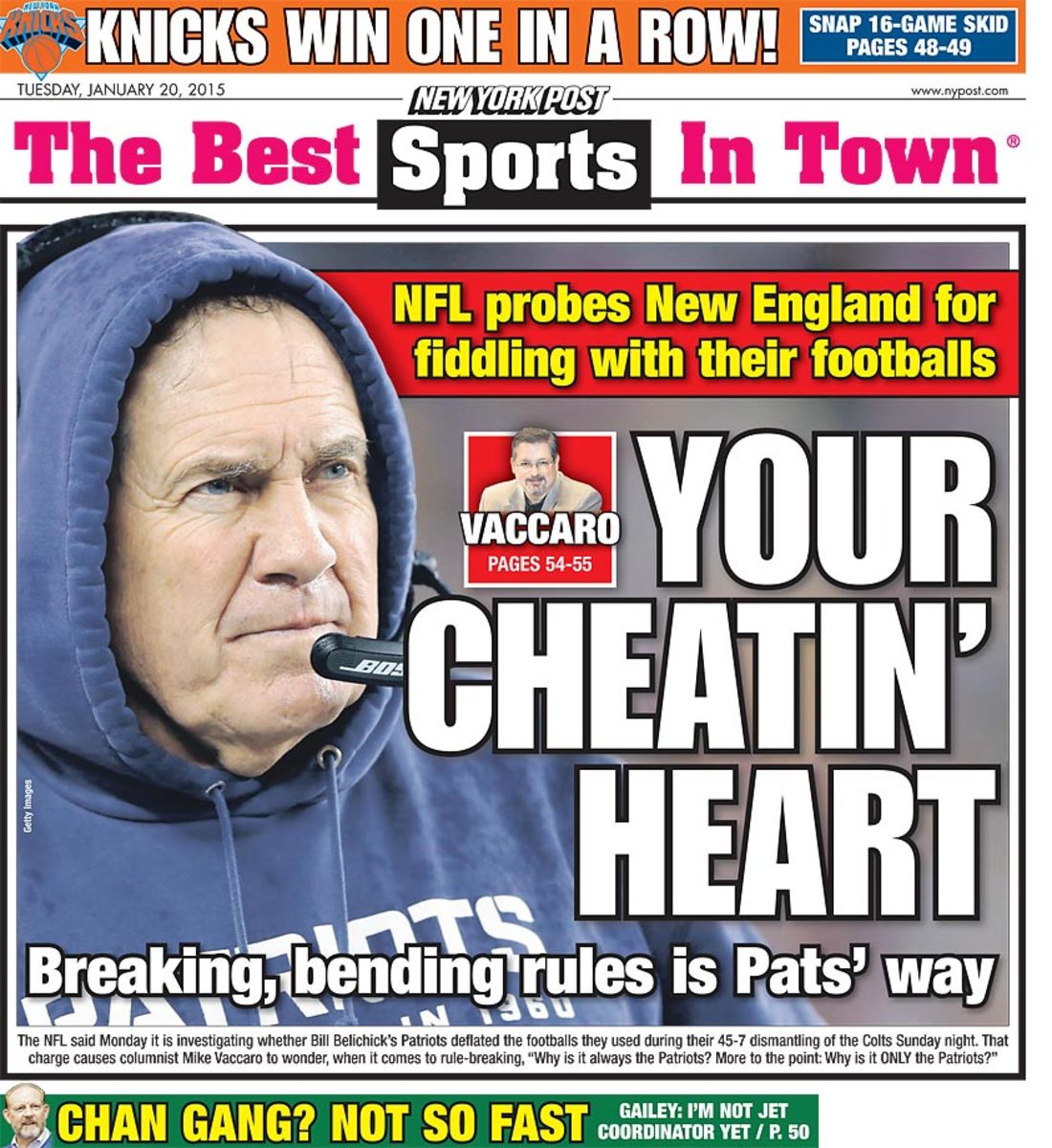

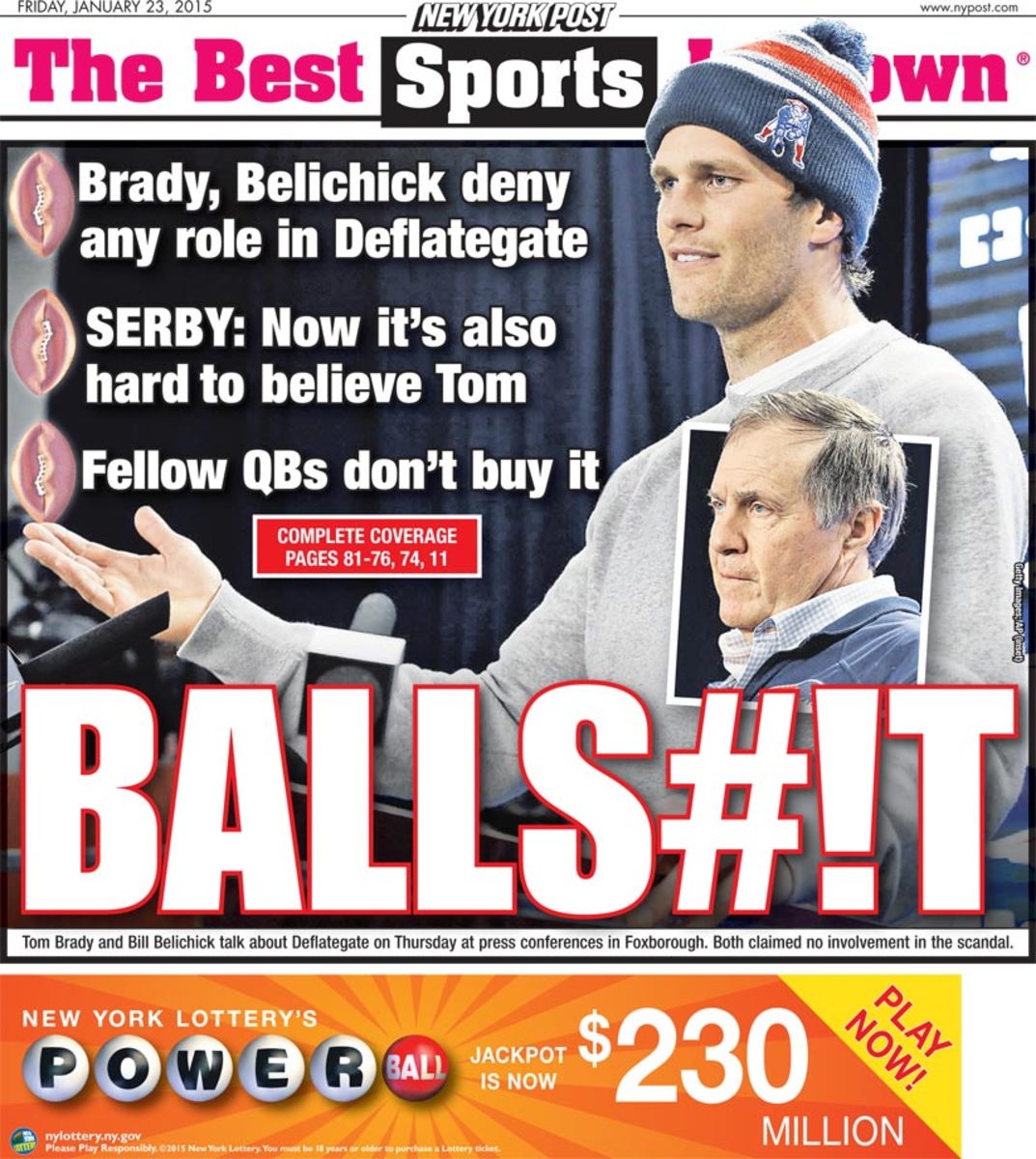

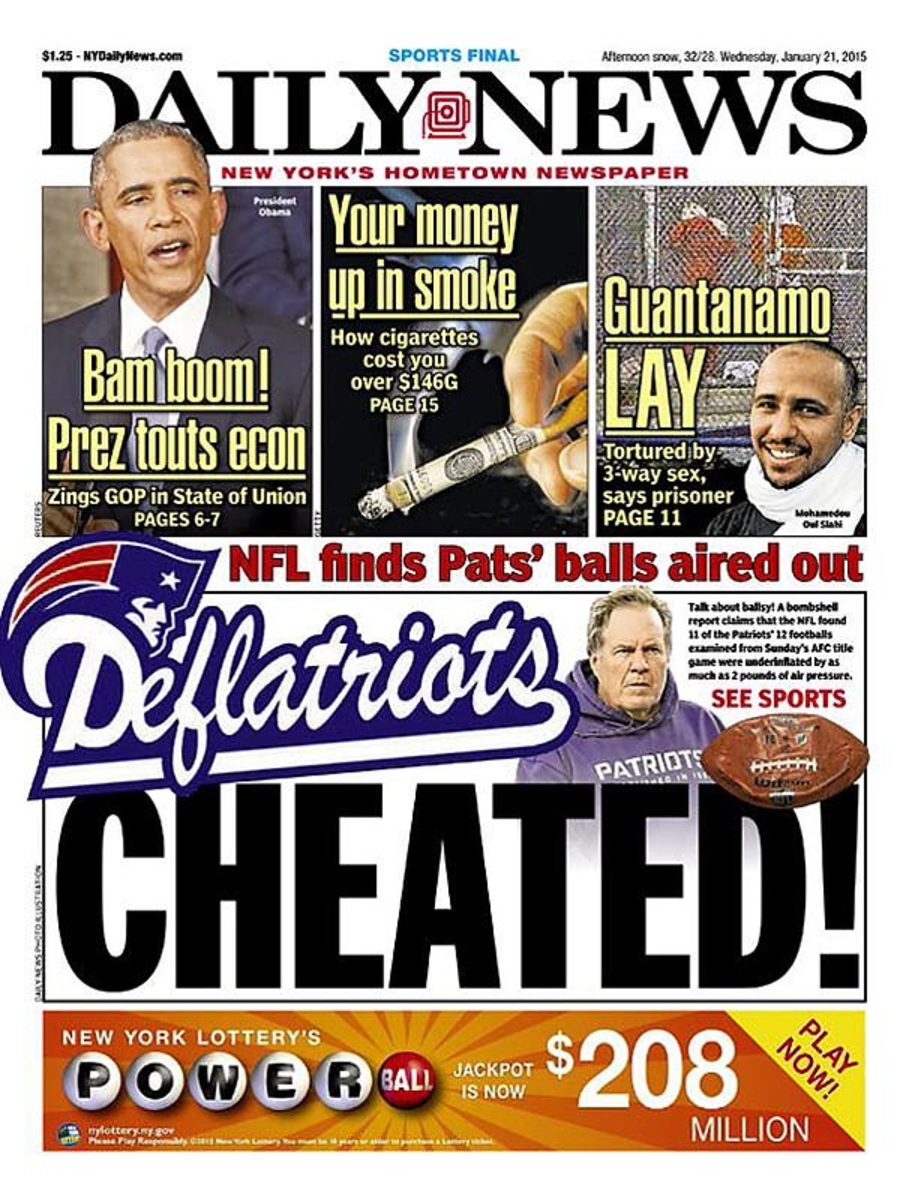

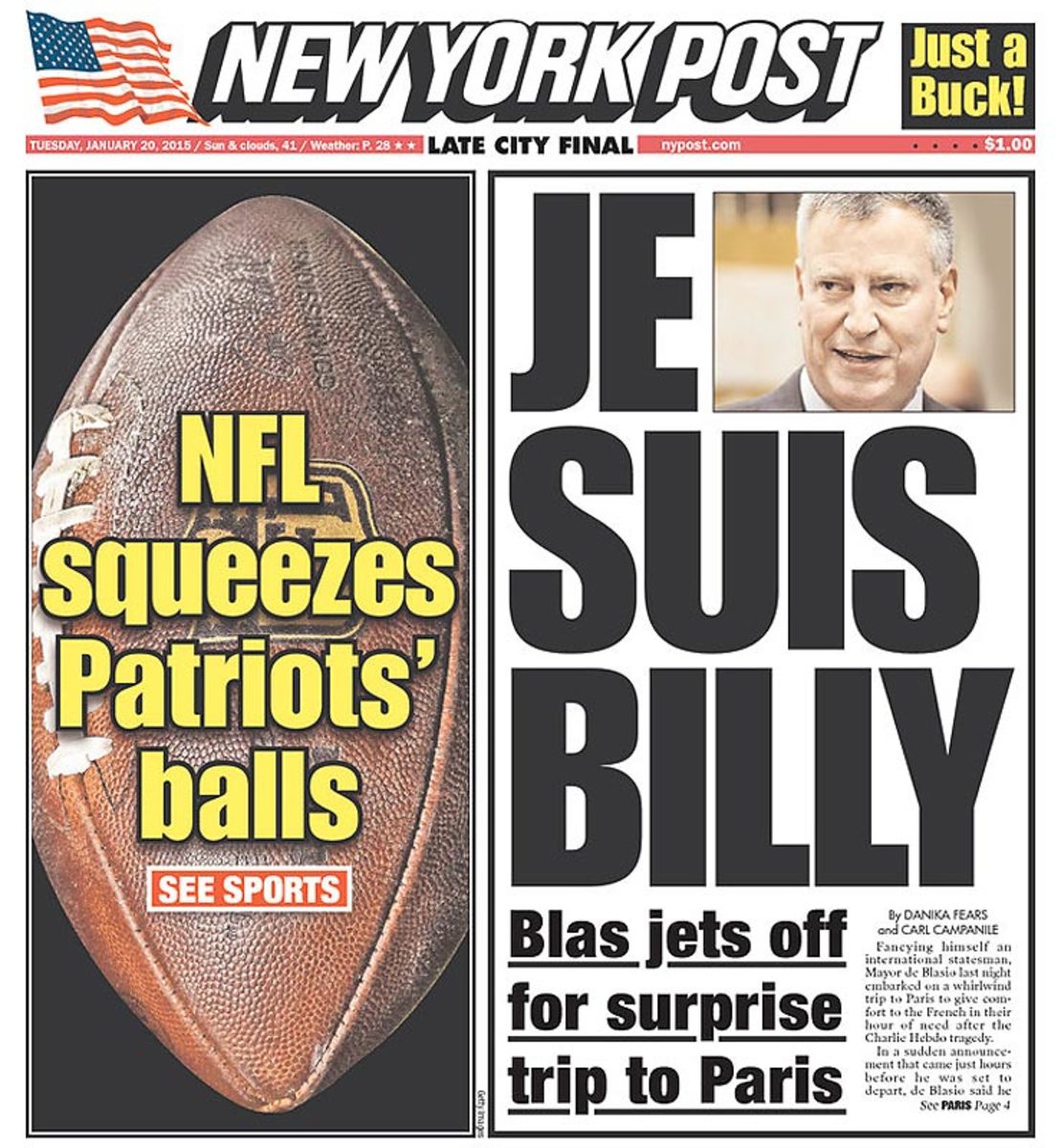

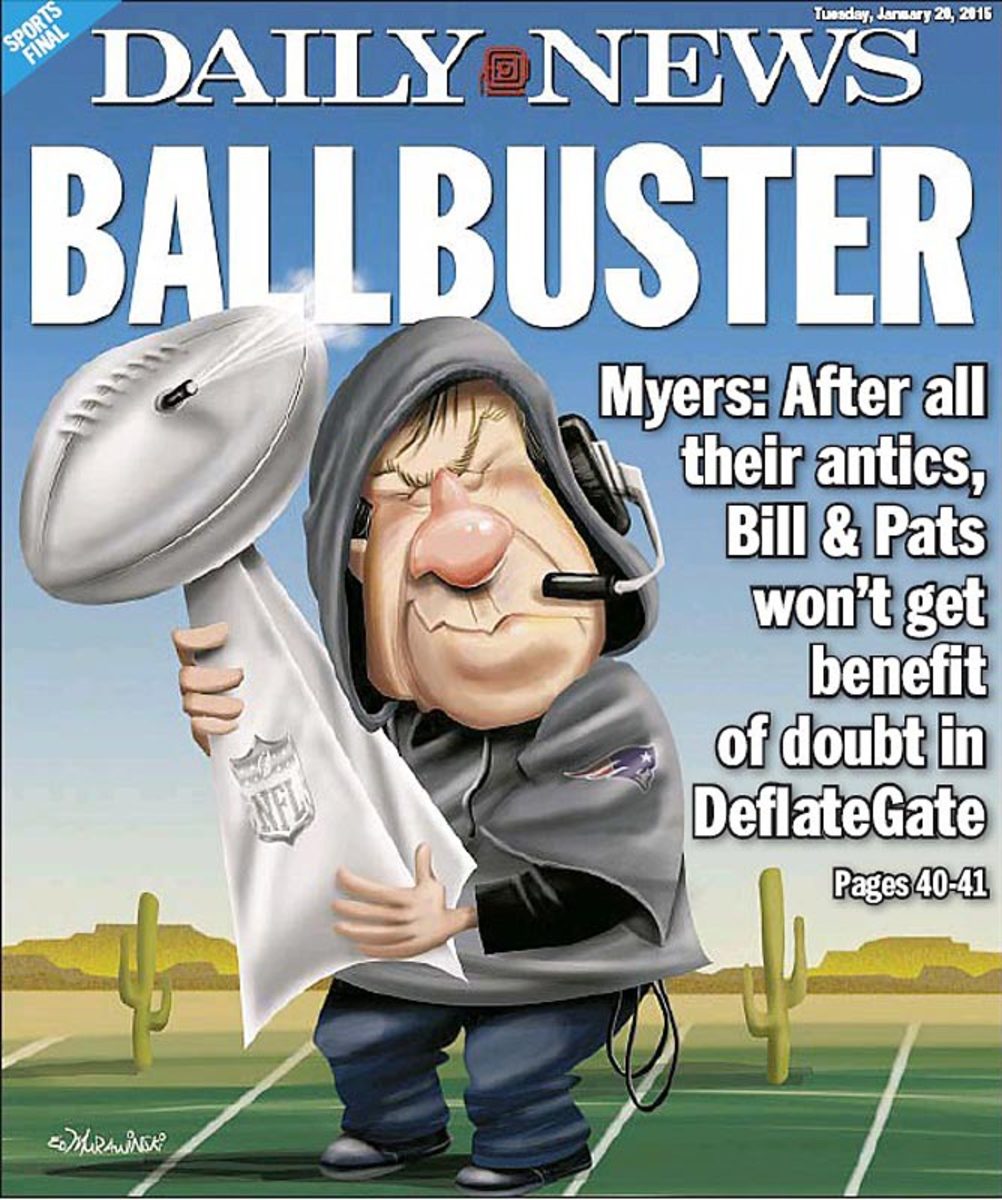

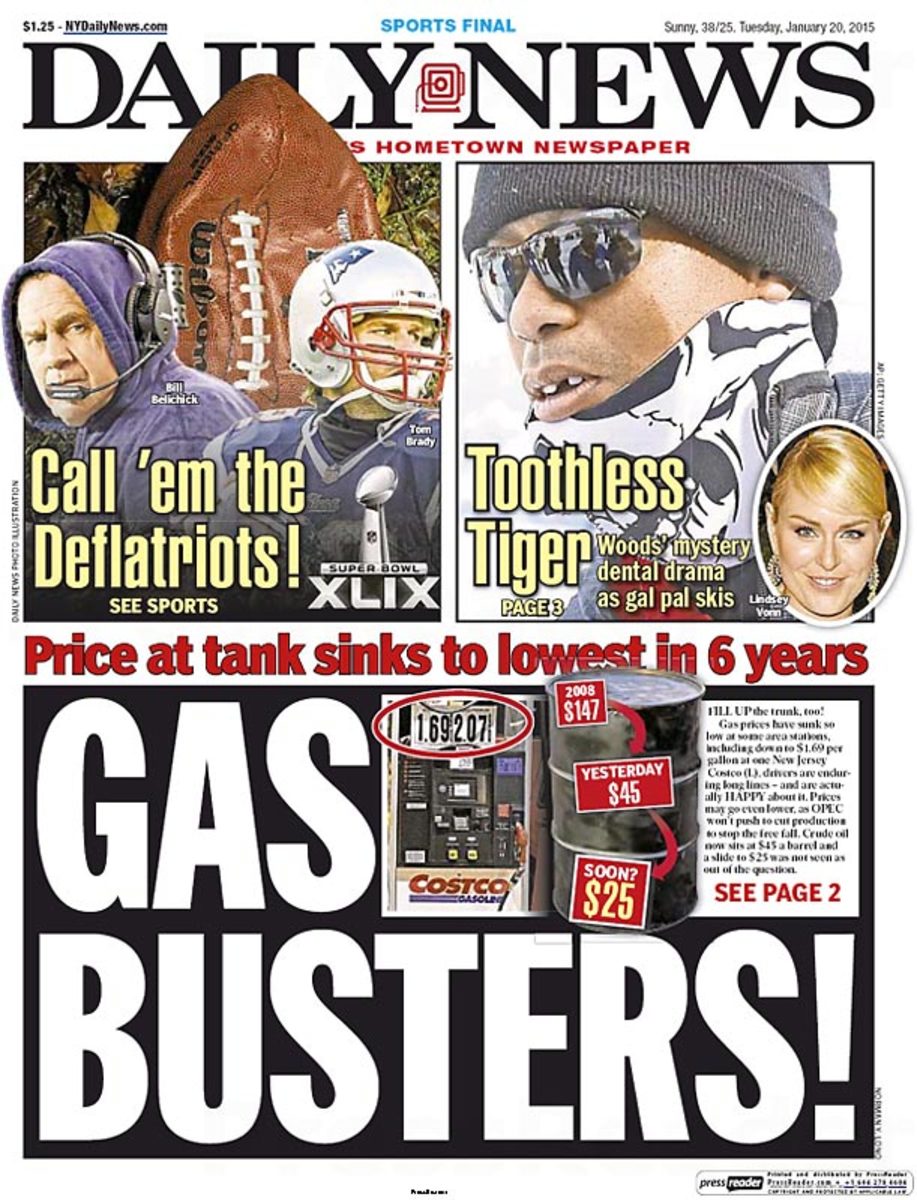

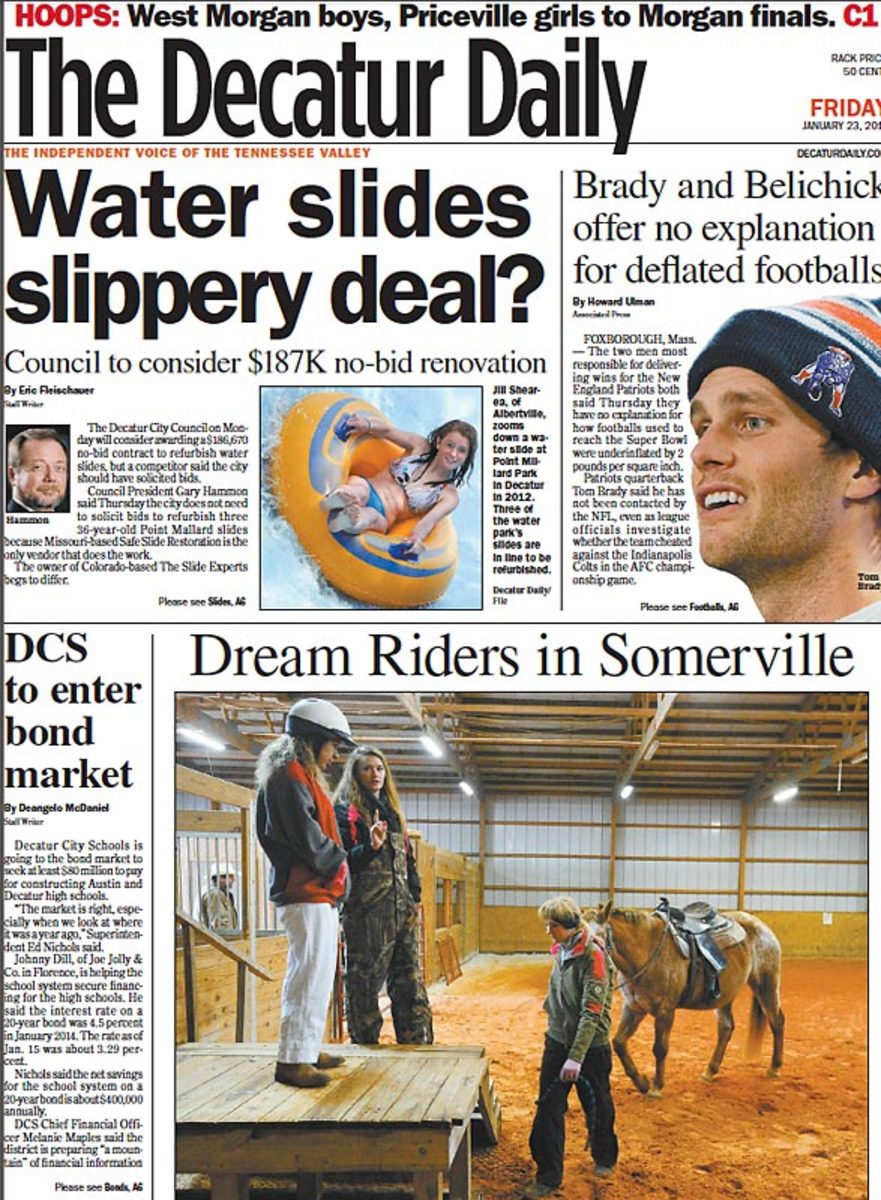

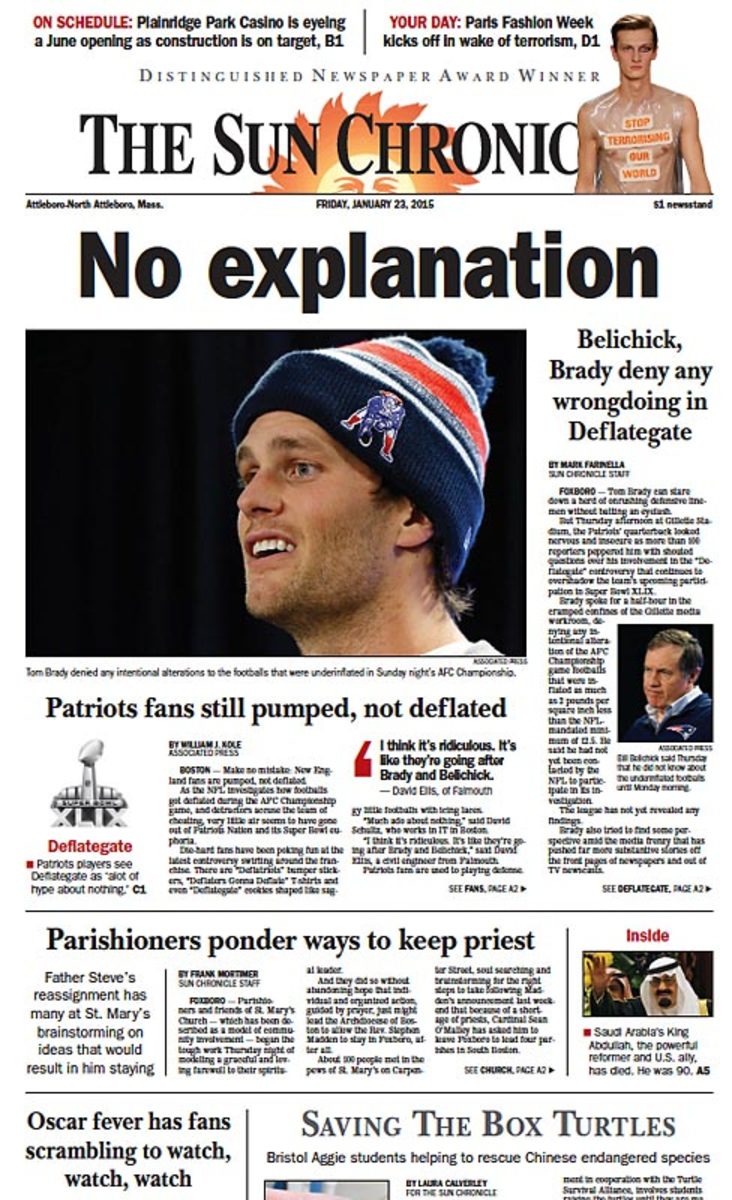

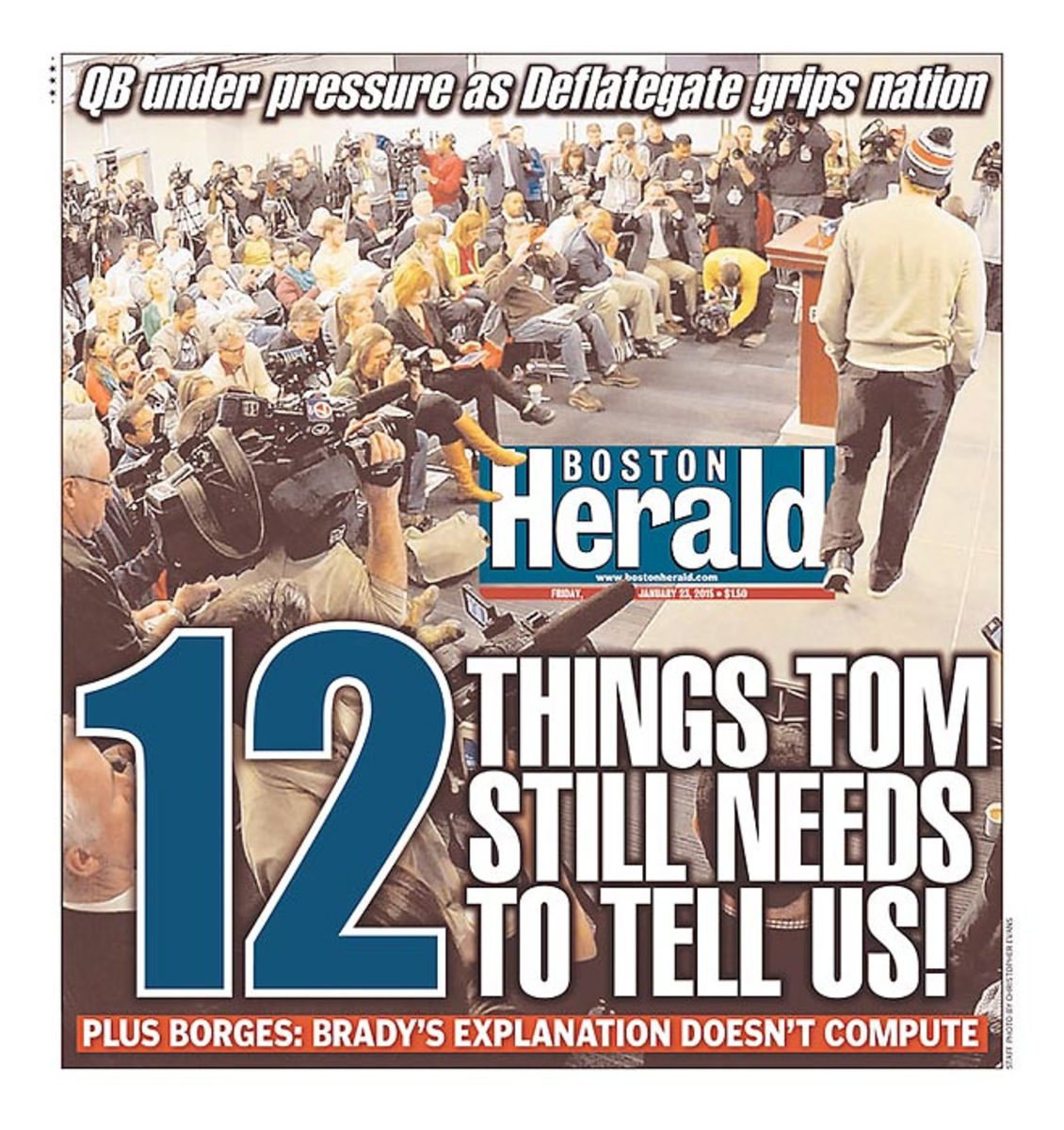

The newspaper headlines of Deflategate

Deflategate Newspaper Headlines

Brady’s decision does not prove the validity of Deflategate

As stressed throughout the litigation, whether Brady did it was not part of the deliberation. In fact, Brady could not introduce scientific evidence that might have fully cleared him and the Patriots; only amicus briefs authored by scientists and others outside of the litigation were permitted to raise such arguments, and judges weren’t obligated to consider those briefs.

Without the ability to challenge the purported facts, Brady had to overcome the extensive deference federal courts are obligated to extend to the decision-making of arbitrators, even arbitrators who also serve as the commissioner of the league handing out discipline. Brady stressed how Goodell failed to explain why Brady could receive a four-game suspension for “general awareness” of an alleged football deflation conspiracy when players who had heated footballs and placed stickum on their hands received, at most, fines.

Brady’s arguments resonated with some of the judges, but not with enough of them. At the end of the day, Brady could not overcome the nearly limitless leeway his union gave to Goodell in Article 46 of the CBA. Further, most of the judges who heard Brady’s case were unwilling to consider rights related to Article 46 that the union failed to negotiate.

Brady can still bring a defamation lawsuit, but don’t count on it

Massachusetts law provides Brady with three years from the date of any alleged defamatory statements to file a lawsuit over them. Brady could sue the NFL, Goodell or NFL executive vice president Troy Vincent, among others. As I explained on Wednesday, however, Brady has many reasons not to pursue such a case. He is a public figure, meaning he would have to prove actual malice (that is, the NFL knowingly lied about him). Brady would also have to overcome language in the CBA that arguably preempts such a lawsuit. Brady would also be working against the judicial proceedings privilege, which makes statements made during legal proceedings exempt from defamation claims.

• From the Vault (2015): Why the Patriots trust Garoppolo to take the reins

The NFLPA could continue the case without Brady

Tom Brady is not the only party in his case. In fact, it was never really “his” case: The official name is NFL Management Council et al. v. NFL Players Association et al. The NFLPA is a party on Brady’s behalf, but also on its own behalf.

The NFLPA’s interests in the case go far beyond Brady, as the union is entrusted with looking out for the best interests of all of its members. The NFLPA is convinced that the NFL, and particularly Goodell, acted outside the scope of Article 46. The union is surely concerned that, unless reversed by the Supreme Court, the Brady case creates a troubling precedent for other players who might be suspended for alleged equipment violations of uncertain scientific merit.

The NFLPA reserves the right to petition the Supreme Court, and it has 90 days to do so. If the NFLPA exercises this right and ultimately wins before the Supreme Court, Brady would be reimbursed the money he will lose as part of his forthcoming four-game suspension (approximately $235,294, thanks to a contract restructuring earlier this year). Brady would also be vindicated in a reputational sense—but only to a certain degree. A victory at the Supreme Court by the NFLPA would not formally clear Brady of the underlying accusations. Brady’s case (or, perhaps more accurately, “the case formerly known as Brady’s case”) is not about whether he did or didn’t do it, but rather whether Goodell lawfully applied the CBA.

The NFLPA’s best remedy to prevent another Brady-like suspension is not through litigation. Instead, it needs to collectively bargain stronger procedural protections for players who are accused of misconduct. Although the current CBA runs through the 2021 draft, the NFL and NFLPA might jointly explore changes to player conduct matters prior to then.

In summary: Deflategate might not be over, but it’s a controversy that is clearly running low on air.

Michael McCann is a legal analyst and writer for Sports Illustrated. He is also a Massachusetts attorney and the founding director of the Sports and Entertainment Law Institute at the University of New Hampshire School of Law. McCann also created and teaches the Deflategate undergraduate course at UNH. He serves on the Board of Advisors to the Harvard Law School Systemic Justice Project and is the distinguished visiting Hall of Fame Professor of Law at Mississippi College School of Law. He is also on the faculty of the Oregon Law Summer Sports Institute.