Newton's Law: Criticize him all you want, but the Panthers QB won't change for anyone

This story originally appeared in the Aug. 29–Sept. 5, 2016 issue of Sports Illustrated.Subscribe to the magazine here.

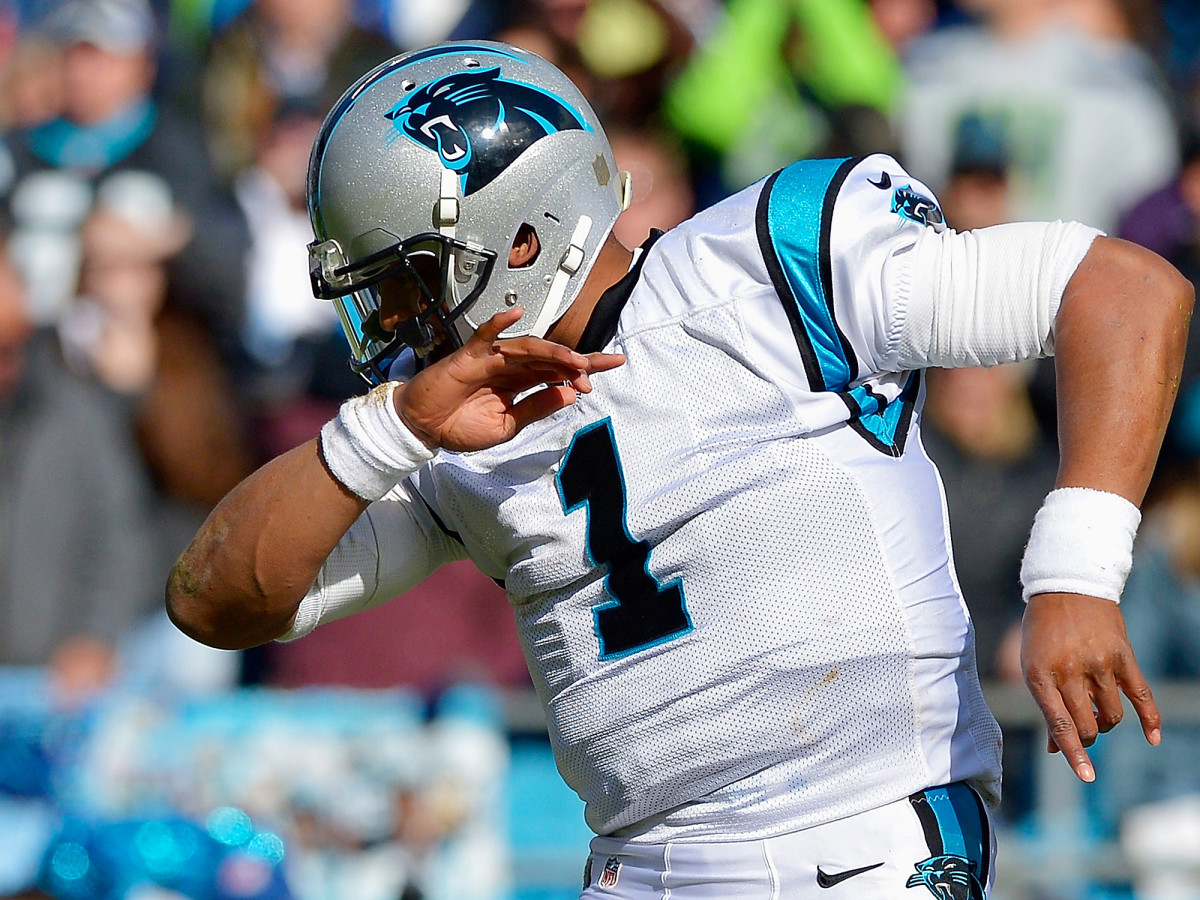

Here's the thing about Panthers quarterback Cam Newton: Even during practice, he performs. There he is in August, white bandana unfurling from his helmet, number 1 jersey rolled up to his chest. He's screaming, darting, chest-tapping, fist-pumping, high-fiving, dancing, smiling, throwing, frowning—and it's only the first week of training camp.

If anyone expects the famous Newtonian exuberance to be muted after his lackluster outing in Super Bowl 50, it's not. Think his confidence might be dented by the vitriol that followed that game? It isn't. He's as demonstrative as ever. If he's thinking even a little about last season—the championship he lost, the fumble he didn't chase, his infamous post-title-game poutfest—he hides it well.

Newton's approach wasn't universally adopted by the Panthers. Some did look back to that big game last February, like coach Ron Rivera, who spent part of this spring researching why no team in more than 20 years had returned to the championship game after losing it the year before. (Buffalo did so in the 1991, '92 and '93 seasons.) Rivera made several phone calls to friends who had lost Super Bowls and a culprit emerged: complacency. He wouldn't have to worry about that with Newton.

Unfiltered NFC scouting reports: Each team's most overrated and underrated player

Last season the quarterback was anything but complacent. Newton won over even casual sports fans with a transcendent style best described in terms like joyful and exultant. After touchdowns he handed footballs to children in the stands. He developed a show for Nickelodeon, All in with Cam Newton. Then he stomped away from his Super Bowl presser after two minutes and 29 seconds, and so much of the goodwill he generated in 2015 evaporated.

Publicly, Newton said little about his team's 24–10 loss to the Broncos or how it ended, with the league MVP being branded the sorest loser in sports. But privately Newton received advice from mentors like Hall of Fame quarterback Warren Moon. They've known each other since 2010, Newton's Heisman Trophy-winning season at Auburn.

Moon reached out first, expressing his displeasure in a two-paragraph missive hours after the Super Bowl ended. Moon told Newton his actions threatened to derail a season in which Newton had cemented himself as one of his generation's best players, a quarterback unlike any who had come before, in skill, style and temperament. Moon knew how Newton's behavior would resonate, even though—let's be honest—Newton had every right to be disappointed. Still, it reinforced his reputation as the league's most petulant QB, prone to mood swings, fine with throwing parties for even minor successes but unable to handle a major loss.

“Those were the things we talked about,” Moon says. “How a quarterback should act. Getting rid of the Dab. Being steady. Managing his highs and lows.”

NFL Week 1 Power Rankings: Panthers enter season-openers atop the league

If Newton changed at all, if he listened to Moon and others, it was not immediately obvious. In his first game after the Super Bowl, a preseason scrum against the Ravens, a simple interception return by a teammate overwhelmed Newton with excitement. He ran onto the field, drawing an illegal-substitution penalty and nullifying a touchdown. This was not a quarterback in control of his emotions.

“You live and you learn,” he told reporters.

“We're moving forward.”

“Next question.”

This time last year Newton faced an entirely different line of questioning that focused on his recovery from the car accident that ended his season in December, 2014. He had been driving to the Panthers' facility on an off day to watch film when his 1998 Dodge pickup collided with another car, rolled over at least twice and landed, smashed up, on its side. His parents, Jackie and Cecil Sr., drove straight from Atlanta to the hospital. Their son had two fractures in his lower back. “He could have been paralyzed,” his father says. “He could have been dead.”

Instead, Newton had “the best camp I've seen from him,” says Derek Anderson, his backup. The accident, by all accounts, changed Newton. It freed him. Newton the performer would play and act exactly how he wanted to, caring even less what people outside of his inner circle thought. Those closest to him think he realized how easily his career could come to an end.

Newton played unburdened in '15, and was seemingly in a world removed from a stolen-laptop incident at Florida (charges were dropped after he completed a pretrial intervention program), a college recruiting scandal (Cecil was accused of shopping his son to major colleges for cash but has denied that any money changed hands) and a 13—19 record in his first two NFL seasons. Last year Newton celebrated with elaborate routines, posing with his linemen, shooting imaginary baskets with his backups, handing out footballs like candy bars on Halloween. He turned a little-known dance from a rap video, the Dab, into a national obsession—and then a national annoyance. (No one needed to see Hillary Clinton, Andy Reid or Al Roker Dab.)

Sure, all that emoting led a parent or two to write critical letters to local newspapers and a handful of older (and mostly white) coaches to complain that Newton's antics violated some unwritten ethical code. But mostly the elation Newton exhibited won over those who had been critical of his past transgressions. They wanted to enjoy something, anything, as much as Newton seemed to revel in each play. His attitude became the season's dominant story line. The Panthers finished 15—1, and the football cognoscenti noticed. Joe Namath, a quarterback famous for his swagger, says, "Cam's style, that joy, speaks to his generation." Don Shula, who railed against excessive celebration when he coached the Dolphins and whose son, Mike, is the Panthers' offense coordinator, says, “It all seems positive to me.” Even Moon, a QB so stoic that teammates called him Daddy Warren, says “I learned from Cam last season. My biggest regret is I didn't have as much fun as I should have. I felt like I was playing for an entire race.”

It frustrates Moon that 15 seasons have passed since he retired from a career built on broken barriers, and African-American quarterbacks are still viewed through a racial lens. He says the criticism of Newton is at least partially motivated by his skin color, even though Newton told GQ this month he didn't feel he was being judged that way. Newton, Moon says, is unlike any previous black quarterback, from his flamboyant outfits (zebra-print pants, anyone?) to his refusal to conform to any idea of how quarterbacks are supposed to act. He is held to a higher standard than, say, Tom Brady or Aaron Rodgers, with every action dissected, every lapse blown up into national news. “That's the thing I don't understand,” Moon says. “The way people react to Cam, you'd think he robbed a couple banks or raped a couple women. All he does is a little dance.”

Season of change: An NFL rookie mom stays calm through life's one constant

When asked about being a lightning rod for criticism in a pre-Super Bowl news conference, Newton said that was a “trick question,” reasoning that he makes some people uncomfortable simply because he defies comparison. At 6' 6" and 260 pounds, he's built like a linebacker, only more athletic, faster and sturdier—a skill set so rare, his coaches at Auburn called him “the dinosaur.” He's just as distinctive off the field, with the foxtails, the funky hats, the Superman swag. He doesn't look or act like a typical quarterback, and he's not about to apologize for what he calls “being true to myself.”

Many in football find his approach refreshing—even Von Miller, the Broncos pass rusher who was last seen trolling Newton after ruining his Super Bowl. “Look at his stats,” Miller says, meaning how good they are, and he is right. Newton is the first player in NFL history with at least 30 passing and eight rushing touchdowns in one season. (He had 35 and 10 last year.) He has the most combined passing and rushing yards in the first five seasons (21,470) of an NFL career.

“If you don't like him, you don't care about none of that,” says Luther Campbell, a youth football coach and organizer, as well as an outspoken record executive who generated plenty of controversy as the front man of the hip-hop group 2 Live Crew in the 1980s and '90s. “I love him because he's not running away from his blackness, like a lot of other guys. They get successful, and they don't want to be black anymore. They want to be like Tiger Woods.”

“People started to come around last year,” Campbell continues. “You know why? Cam is real.”

Driven by his own expectations, Trai Turner has the Hall of Fame on his mind

The Newton who showed up for the Super Bowl did not resemble his true self or any other version. He didn't score, so he didn't Dab, and he had no footballs to give away. The Broncos took a 10–0 lead in the first quarter behind a field goal and Miller's strip-sack of Newton, which teammate Malik Jackson recovered in the end zone.

Anderson stressed the positives to Newton on the sideline, reminding him of the “lulls” Carolina had overcome in previous games. There was the comeback victory at Seattle, Newton's pivotal moment in '15, where he led two scoring drives in the final 8:08 to seal a 27–23 win.

Against Denver, there was no rally. The Broncos stalked Newton, harassing him into 23 incompletions and three turnovers. At halftime Newton told Anderson he was seeing the field well and felt confident about the game plan. But nothing changed in the second half. The image that endured was Newton, late in the fourth quarter, choosing not to dive on a fumble, as if the Broncos' dominance had forced him to second-guess himself.

After the game, reporters asked Newton at least 13 questions, which he answered with a hoodie pulled over his head, eyes narrowed. Eleven of his answers were delivered in three words or fewer. He bounced after that, leaving his teammates behind, and that changed the tenor of his season.

Meanwhile, Anderson says, “I don't think everyone understands what's going on there. He's sitting right next to the Broncos, separated by a curtain, and he can hear them celebrating. He was frustrated. People don't understand the sacrifice, everything you go through to get to that point and come up short. It's hard.”

Newton left the stadium and spent most of the next six months underground. Miller, Newton's Super Bowl foil who made what seemed like a million public appearances in the off-season, says he understands. “I don't get why people gave him such a hard time,” Miller says. “How do you gracefully lose the Super Bowl? You shouldn't expect grace then.”

Moon cringed when he saw the postgame episode on television. He thought back to his most difficult press conference, after Buffalo erased a 32-point deficit against Moon's Houston Oilers in a playoff game to complete the biggest comeback in NFL history, and how he had stood there, crushed but available, emphasizing that his statistics didn't matter, that they had lost as a team. He had acted, Moon says, like a quarterback.

“With Cam it goes all the way back to Auburn, back to Florida,” Moon says. “He's not shy. He's not quiet about promoting himself. The thing I told him is, I don't mind the highs. But quarterbacks can't get that low. They represent too much.”

Upon review, Newton's position coach, Ken Dorsey, says his quarterback's actions after the game graded worse than his performance during it. Newton had not executed poorly, Dorsey said, except for the turnovers, “critical errors” that played a major role. “I don't think what happened there diminishes anything he did last season,” Dorsey says, perhaps wishfully.

It's May, and Newton resumes work in the shadow of downtown Charlotte. He's still animated, still screaming, still dancing, running 50 yards across the field to celebrate one score. He meets with the Panthers' beat reporters, who have not spoken to him as a group since the Super Bowl. Moving forward, Newton says. Focusing on 2016. His answers are different now, more guarded, as if he's channeling Bill Belichick.

Newton made just a handful of public appearances during the off-season. He hosted a charity kickball game while wearing UGG boots. He sang “Nice and Slow” by Usher during a radio appearance. He penned a short tribute about Muhammad Ali for The Players' Tribune. He filmed the Nickelodeon show at an animal hospital, a basketball court, a BMX track and the White House, where he interviewed Michelle Obama. For Father's Day—the first he was celebrating with his son, Chosen, who was born last Christmas Eve—he went to a Target store in Charlotte and bought gifts for kids who came to get something for their dads.

The Newton the public didn't see was at the team facility more this off-season, after spending previous springs at Auburn to finish his undergraduate degree in sociology. He graduated in May 2015. “Cam has been pushing guys,” says receiver Kelvin Benjamin. “Talking to guys, telling them to forget about last year.”

Newton, his father says, will not change for those who want him to be less visible, less flashy. In sixth grade a teacher criticized Newton for talking too much in class, so Cecil made him wear dress slacks and a tie to school on Fridays. He didn't stop dressing that way when the punishment ended. He woke up early and ironed his shirts, and his classmates started coming to school in the same clothes. "He's always had a strong will to self-identify," Cecil says.

Those who spend any extended time around Newton say he cares little about celebrity, that it isn't fame that drives him. They weren't surprised by his quiet off-season and felt he would have been criticized regardless of whether he is outspoken or not. “Famous people get caught up in being famous,” says Ice Cube, the rapper-actor who befriended Newton a few years ago. “Cam's not like that. He's himself, and he can't win. People hate that he's outspoken. But they hate the humble guy just as much.”

General manager Dave Gettleman says critics overanalyze Newton, forgetting that he started just one year in college, in Auburn's simplistic spread offense. He arrived at an MVP season through four years of gradual improvement. “I don't think he's peaked yet,” Gettleman says.

Moon says the Panthers have tailored their offense to Newton's strengths in recent seasons, calling for more deep passes and designed QB runs. As training camp approached, the text messages between Moon and his mentee continued. Moon emphasized balance, Zen. “He doesn't have to be perfect,” Moon says, “but he has to decide how much of his emotion is productive.”