Playing Through the Whistle: The story of steel, football and American town Aliquippa

The following is excerpted from PLAYING THROUGH THE WHISTLE by S.L. Price. Copyright © 2016 by S.L. Price. Used by permission of Grove Atlantic, a division of Atlantic Monthly Press. All rights reserved.

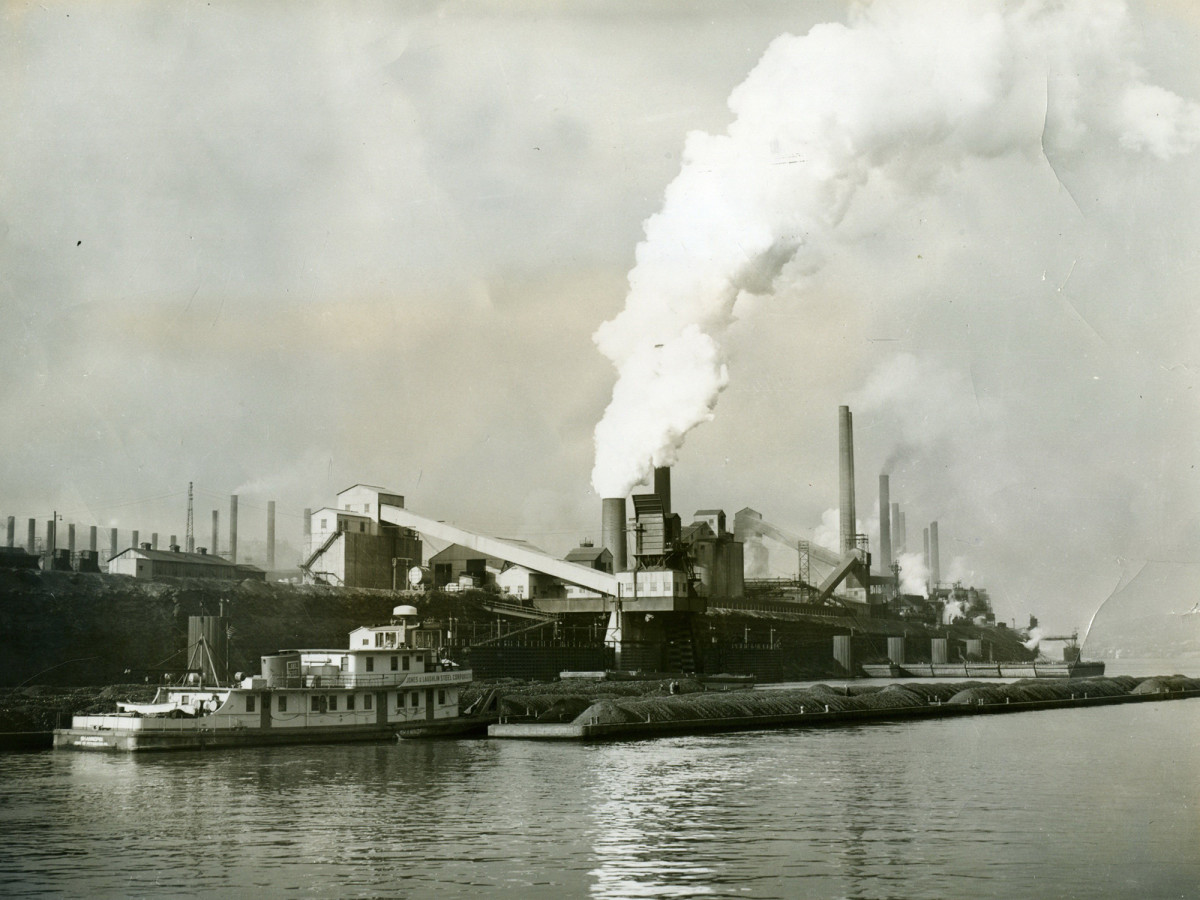

The children being born then, after the Jones & Laughlin steel mill died, would live unburdened by the knowledge that the town had once been anything but sinking. Maybe that was better. Remembering could be a curse. The generation that grew up with dads hauling themselves off to work, that witnessed Aliquippa's meltdown, couldn't help but dwell on the better days. Some got stuck there.

"We had Sol's Sporting Goods; bought a little football there," said future mayor Dwan Walker, son of Chuckie and Chedda, born in 1975. "Woolworths, the grocery store. Downtown was awesome. On Friday nights you'd go to the drive-in. Softball games, old versus the young; play down at the playground. Used to go blackberry picking and sell them to the older ladies on our streets. Used to go crayfish picking in the creeks. It was fun then."

Dwan, who would one day play receiver for Aliquippa High, and his identical twin, Donald, went everywhere together, looking so much alike that people gave up and took to calling them both Twin. And the twins said "Yessir" and "No, ma'am." They weren't alone: All their friends, when some lady would call out, had been raised by parental belt and glare to stop in their tracks and respond, "Ma'am?" But they were the last of that breed.

Christmas '87: That's when the boys started feeling it. Before that, a spray of toys and sports stuff would roll out from under the big tree, cover two-thirds of their living-room floor; as an electrician, Chuckie Walker had been making $18.75 an hour at J&L, base, with as much overtime as he could handle. In his best years he was pulling in nearly $70,000, enough to buy a good car, a house, drive the family out to Oklahoma each summer and even, once a week, take the whole brood to Long John Silver's.

Then that stopped: The Christmas booty dried up. There was maybe a board game and some small trinkets now, the merciless accounting of two 12-year-old boys: What? This is all we're getting? And their father would drift out of the room, quieter than usual.

Playing Through the Whistle: Steel, Football, and an American Town

by S.L. Price

Once the steel mill closed, the only source of pride in Aliquippa, Pa., was high school football. But could even star players survive the town’s descent into drugs and crime?

Now Ty Law was coming. He was going to be the Next One in Aliquippa High football, the heir to Mike Ditka and Sean Gilbert. Anyone could see that, ever since the wet day he was playing Midgets at Carl Aschman Stadium (aka the Pit), a championship game no less, and his cleats got stuck in the mud and damn if the kid didn't run right out of his shoes and race 65 yards in socks for a touchdown. First year with the Quips, 1989, the swift, tough sophomore showed he could do anything—run, receive, patrol the defensive backfield—and coach Frank Marocco won an AAA Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League (WPIAL) title in his first season.

But there were problems. Crack use was growing, its acrid scent wafting through the Linmar and Valley Terrace neighborhoods, through the Plan 11 quadrant known as the Funky Four Corners and through Wykes and Davis Streets in the Plan 11 extension to the west, where Ty lived with his grandfather Ray. Football and the drug trade had become the town's most thriving concerns, and it took no time for the line between them to blur.

Ty wanted a new pair of Air Jordans. He wanted cash in his pocket, to feel like he was something to see. Being a football star wasn't doing that nearly as much as it used to; the dealers were getting all the play. "That's what got the girls," Ty said. In the summer of 1990 a cousin of Ty's fronted him some product so he could ride around in a car and sell it out the window. He dealt crack for about a month.

Ty wasn't very good at it. The whole exercise made him uneasy. First, there was the fact that his mother had turned their home upside down with her own drug use, and here he was peddling the same poison to other guys' moms. Then there were those disquieting moments when some lady his mom's age would offer sex for the drugs he was selling, which made the 15-year-old Ty queasy. Because then he had no choice but to wonder: Is my mom doing that?

It was also hard for him because in lucid moments Diane Law tried to be a parent. Once that summer she stumbled across his stash of cocaine and screamed at Ty and said she'd flushed it all down the toilet. But deep down Ty knew. Intentionally or not, he'd supplied his mother. "Come on, man," Ty said. "Drug addict ain't going to flush no drugs."

Then there was one hot night on Wykes Street, when a guy Ty was snapping at about something small—a girl, an insult—pulled a gun and jammed the barrel against Ty's head. "Say something!" he demanded. Ty didn't, but the shame of being made into a punk and the cold fear that he'd felt: It made him crazy. He ran home to his grandpa's house, to the closet where Ray kept his hunting rifles and handguns, and grabbed a long-barreled pistol and headed for the door.

His grandfather chased him. Ray Law hollered, Why? and tried to stop him, but how do you stop a 190-pound whirlwind of teenage muscle with a loaded gun? Ty bolted from the house. He fired the gun into the night air as he loped down Wykes, getting two or three shots off before the other guy crouched and fired back, and it sounded like rockets vrooming past. Oh, s---! Ty thought, and he turned tail and got out of there.

But it wasn't the flying bullets, the nearness of death, that made Ty quit dealing. It was his grandfather's shocked and fallen face, first when Ty pushed past him and then when he came home. Ray had always been Ty's ally against Diane's addiction, but now the boy saw a new heartbreak in the old man's eyes. Ray did everything for Ty: spoiling him, talking him up in the neighborhood, even taking real ketchup to school for Ty to put on his lunch hot dogs. Because the boy was good—Ray just knew it—and was going to make good too. Ray had had no idea that his grandson was dealing, no idea that he'd bottled up that kind of rage. But now he could see it: One daughter down, and my grandson hitting the same path.

"My grandfather was scared to death," Ty said. "He'd never seen that. It did something to him."

Is it any wonder, then, that in Aliquippa, late in the '80s, the game got bigger? Once merely the vessel of local pride, football now assumed even greater import. It was as if those who remained sensed the worst: This is what is left. Football is the endgame, the gritty final distillation of the dream that our great-grandfathers came here to dream, the one proven process that can still result in a scholarship, a way out, maybe big money.

There were a few dissenting voices. Melvin Steals, an English teacher at Aliquippa High, was named the city's Teacher of the Year in 1984. He spent most of the decade working on postgraduate studies in education. While researching a support system for high school student-athletes, Steals said, "I solved the major mystery: I began to realize the true meaning of a student-athlete.

"Aliquippa was a plantation system. People said, '[Former coach Don Yannessa] could get a rock into college'—and he did. There was a kid whose nickname was Killer Rock—and he got Killer Rock into college. But by the second or third game of the following season, they began filtering back into the crowds at the [Quips games]. Because they were not academically prepared to meet the rigor of postsecondary learning."

In his 1989 doctoral dissertation at Pitt, Steals appended the Aliquippa school system's '88 results on the California Achievement Test. "By the time the kids had reached 10th grade, 60% of the students, white and black, were reading below grade level—and 62% were performing below grade level in math," said Steals, who departed Aliquippa High in 1989.

But such bad academic news provoked little outrage at football or Yannessa. If anything, it reinforced the belief that athletics was the prime ticket out, an all-or-nothing proposition that, incidentally, announced its winners and losers each week in newspapers and on TV. And with such an atmosphere settling in, the town assumed an all-in tone about the team, darker and meaner and more urgent than ever before. When a season ended without a title, players were told by brothers and friends and mouthy fools, Y'all suck!, but now it was harsher, less joshing.

Ty Law would go on to play at Michigan, then become the best cornerback in the NFL after breaking in with Bill Parcells's Patriots in 1995. He would lose pro playoff games that cost him hundreds of thousands of dollars, but nothing hurt worse than the seven obscure defeats that he experienced as a Quip.

"It's like you've lost everything," Law said. "Nobody in the damn neighborhood wants to talk to you. It's rough: 'You lost to them? What the hell? You all suck!' And they ain't just fans. We used to go down to a friend's house, go hang out after, drink a couple beers ... and boy, if you lose? That's not happening.

"Even in the pros, there was nothing they could say or do that I hadn't already seen or wasn't prepared for. Coach Parcells is known for always messing with the first-round guys; he tried to give it to me every day, and I'm like, I've seen way worse than this. I looked at Parcells, like, Who are you?"

Still, during Ty's senior year at Aliquippa, the world became all kindness and light. He was named a Parade All-America while leading the Quips to their first state title. That was in 1991, a year after the Quips dropped to AA, but what of it? Aliquippa avenged an early season loss by edging Riverside and won the WPIAL, then rolled over Forest Hills 20–6 to set up a state-title showdown with defending champion Hanover, winner of 30 straight, in Pittsburgh's South Stadium. But that challenge was nothing compared with the gut-wrencher Ty had faced right before.

Because on that December Saturday morning, along with two teammates, Ty had to take the ACT at Moon Area High. And he had to pass if he wanted to play Division I-A college ball. Georgia Tech, Pitt, every school with an eye on a national championship wanted him, but this was Ty's second try at the ACT. "I had to make it on this one," he said. And then, right after the test, there was a state title game to get to, fast.

Ty finished the ACT after noon and felt pretty good. (He passed. His two teammates didn't.) A police escort led them on the 20-mile sprint into Pittsburgh, where the teams were already warming up. Ty never had a chance to stretch; he was still tucking in his shirt while waiting for the opening kickoff.

Teammate Dorian Jackson fumbled, and the ball landed in Ty's hands. He ran 61 yards for the touchdown. This time he kept his shoes on. Aliquippa crushed Hanover 27–0. "Crazy, crazy day," Ty said. It was, but that was only appropriate. "When we went to football games, we were going to wars," said Donald Walker, who played for Coach Marocco three years later. "We'd close the doors, and he'd say, 'If you don't like what I've got to say? Get the f--- out. These mother------- are coming up here to our house and we're going to f--- them up! Italian and blacks! Go kick their ass!' That's how he talked. You wanted to kill for that man."

Later that month one of Marocco's assistant coaches, Peep Short, rolled late at night through the Plan 11 district in a Beaver County Sheriff's cruiser. He recognized a tall figure walking alone. Short didn't coach Mike Warfield when he was the Quips' quarterback in '86, and he hadn't known that Warfield was back, home for good after graduating from little Catawba College in Salisbury, N.C., having passed for nearly 7,000 yards there. In a flash Short toted it up: ex-baller, no father, bored and at loose ends. The next step was usually trouble.

"Get in," Short said. Warfield opened the cruiser door, and they sat talking.

"What are you doing?" Short said.

Warfield didn't know. There wasn't a plan. He hadn't been drafted by the NFL.

"You want a job?" Short said. "Come down and put in an application."

Warfield had always wanted to be a cop, and he did need a job. For the next 18 months he worked at the Beaver County Sheriff's Office. On many shifts he would ride with Short, serving search warrants, talking football. Short knew nearly every dealer, thief and gangbanger; some colleagues muttered that he knew them too well. But even those who would later decide that Peep Short was all kinds of dirty will tell you: He had guts. "A lot of people would say, 'Short, man, you know me, you're my boy, we grew up together,'" he said. "I said, 'If you're doing something wrong, and you see me come through your door? Then duck.' Because I'm coming through there for business."

In September 1987, Della Rae Campbell gave birth to a son, Tommie, who one day would become yet another Quip to make the NFL. Peep Short wasn't a factor in Tommie's early life, but rumors flew and Della wasn't shy about feeding them; after Tommie graduated from high school, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette called Short "Campbell's father." At the same time many locals, including Della's longtime boyfriend, Rick Hill, remained sure that Tommie's dad was the man for whom the boy was named: Della's former husband, Tommie Campbell Sr.

Tommie's patrimony remained a mystery for a simple reason. "I don't know," she said. "When I had married Tommie Campbell Sr., I was dating Peep Short. I only married Tommie Campbell Sr. because my mother was telling me that I wasn't grown, that I don't need to be going out every weekend. I'm, like, I'm 19 years old! I just went and got somebody and got married."

Later, while moonlighting as a security guard at Valley Terrace, A Building, Short would watch little Tommie compete with the other kids, "and if he wasn't crying, he was fighting," he said. Yes, Short admits, the boy reminded him of himself.

But when asked, he won't confirm or deny that he's Tommie's dad. His discomfort, it seems, lies more in taking credit than ownership. "Any man would be proud to be his father—and I told him that," Short said. "That's all I'm going to say. Because I don't like this Johnny-come-lately s--- where all of a sudden he's in the pros and I'm his dad."

Ty Law began noticing it his senior year at Aliquippa: His things were disappearing. One trophy gone, then another. Then a letterman jacket. It took a while for it to sink in: Oh, damn. She's selling 'em off. His mother was peddling his valuables to buy crack. How could you? I'm your son. You love this drug more than you love me.

Worse yet, Ty would find that Diane was selling the totems of his growing name to a local doctor, a white man to whom Ty had long looked up. The man was buying stock, getting in at crack-rock-bottom prices. "He thought I was going to do something with myself and he'd have some Ty Law memorabilia," Ty said. "And it went on through when I was in college."

The only respite from Diane's problems came two weeks each summer, when Ty flew down to Dallas to visit his distant uncle Tony Dorsett. He and Dorsett's son, Anthony Jr., would work out with Tony and Cowboys stars such as Everson Walls and Ken Norton Jr. and listen to Tony's tales, all the little backstories behind the nearly 13,000 NFL rushing yards and that surefire induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. More than once Tony caught Ty staring at his Heisman Trophy. "Man," Tony jabbed, "you got to be a bad boy to get one of them."

That was the carrot, leading Law on every day. Not that he thought he'd win the Heisman—he knew his future was as a cornerback, and corners don't win Heismans—but Dorsett was an Aliquippa guy, one who knew what it meant to have an old man working the mill and a family with drug problems, and he had made it out. Gorgeous house, nice cars: It could be done. "Tony Dorsett saved me as well," Ty said. "Because after my grandfather, I was looking at him. I was like, This is where I want to be."

But it wasn't just want: Ty needed more. By the time he enrolled at Michigan, he had seen enough of Aliquippa. He was convinced that only money could end his grandpa's worry, solve his mom's drug addiction. Going to Ann Arbor, Ty wasn't worried about getting a degree. He needed to get to the league. He needed to get paid. "I'm thinking you can buy your way off of drugs," he said. "Come to find out that ain't the damn case...."

But that understanding wouldn't land for more than a decade. No, even as he put off older teammates by refusing to redshirt and bragging that he wouldn't be there long—and then by becoming the first true freshman ever to start for the Wolverines—even as he disappeared from campus and raced the four hours home to shield Ray from some episode of Diane's drug use and then drove all night back to make it to morning class, Law had no doubt. The money would fix everything.

All kinds of people tried to persuade Law to stay for his senior year. His name was only then becoming widely known; yes, he was a newly minted All-America, but NFL "experts" projected him as a fourth-to-seventh-round draft pick. A Wolverines strength coach told him, "What are you going to make? Two hundred thousand? Three hundred thousand?"

But none of them knew. In his junior year Law had learned that Ray had filed for bankruptcy and lost the Wykes Street house after taking out a $5,000 loan. For Ty. To buy him that used Chrysler LeBaron for those journeys to and from Ann Arbor. The old man tried to assure him that things would be fine, but Ty was scared. Two to three hundred thousand? he thought. Sounds good to me! Besides, he'd seen the other so-called top college defensive backs. He knew he was better.

"I knew that if I worked out I would go higher than projected," Law said. "I was, like, I'm going to get my granddad's house back and get my mom up off these drugs."

On April 22, 1995, the Patriots made Law the 23rd pick. "I bet on myself—and I won," he said. His mother was with him at Champs Sports Bar in Aliquippa when he took in the news, and a newspaper's camera captured him squeezing her tight. The experts were all wrong. The contract would be for five years and $5.5 million—worlds more than he'd ever dreamed. But what Law remembers most is grabbing his granddad, who'd raised him like a son and never let him down. The two hugged hard.

That was a great story—for a day. But once the local writers filed their copy and the television news aired the footage, reality settled back in. Ty Law? A once-in-a-generation talent hitting the lottery. The rest of Aliquippa? Minimally skilled, and realizing at last that the mill was never coming back. The slow exodus continued. Families tapped connections in Phoenix, the Bay Area, New Jersey, and soon their cars were packed, their houses were empty, and they were gone.

Western Pennsylvania, by the 21st century, had become legendary among football cognoscenti for producing greatness: quarterbacks Johnny Unitas and Dan Marino from Pittsburgh, Joe Namath from Beaver Falls, Jim Kelly out of East Brady, Joe Montana from Monongahela. Everyone credited the area's steely backbone and coal-dusted lungs, the dead or dying industries that made kids hungrier, tougher, more desperate. But few places in the state, much less the U.S., kept spitting out talent like Aliquippa.

Just in 2003, Aliquippa had Ty Law starring for New England's record-setting defense, intercepting Colts QB Peyton Manning three times in the AFC championship game and winning his second Super Bowl. Aliquippa had Sean Gilbert finishing up his solid 12-year NFL career at defensive tackle, and so what if his Raiders teammate, eight-year NFL vet Anthony Dorsett Jr., went to school in Texas? He was born in Aliquippa too, when his dad, Tony, was a high school freshman. "All those examples helped me, because you see that you can make it," said Darrelle Revis, the Jets' star cornerback. "It seems like you're attached to it when you see them play on Sundays, or you see Mike Ditka on TV. You're proud: He's one of us. He's a Quip. That's the best of the best."

By 2003, his senior year at Aliquippa High, Revis owned the game. Running back, defensive back, kick returns: He did it all. In the state championship final, against Northern Lehigh—a team that had allowed just 47 points all season—he scored five touchdowns, intercepted a pass and even completed a pass in Aliquippa's 32–27 win. Oh, and he had five solo tackles.

Tommie Campbell emerged in Revis's wake as Aliquippa's Next One, an all-state wide receiver–safety who won a WPIAL track title in the 4 × 100 relay in '04 and WPIAL gold in both the 100 and 200 meters in '05. The Quips were in contention for the '05 state team title too, but Tommie had been so ill the night before that Sherman McBride, the offensive coordinator who doubled as the track coach, drove him to a Walmart for NyQuil, and when he woke that morning Tommie nearly emptied the bottle trying to calm his nerves. He had five races to run. He almost quit.

Instead, 75 minutes later he survived the 100 and then the 200 semis. At 12:15 p.m. he ran 10.65 seconds to win the 100 final. Then, with Tommie anchoring, the Quips won the 4 × 100 relay. Now Tommie's gut was heaving. And he had to finish at least second in the 200 for Aliquippa to earn the championship.

At 2:13 p.m., as he was setting his feet in the blocks, Campbell dropped his head and vomited. The gun sounded, and he staggered through the first turn. It looked as if he might finish last, but then, with the words Come in second, we're going to win pounding in his head, Tommie summoned one last burst. He finished second, a quarter-step behind the winner, in 22.42. That gave Aliquippa the AA state title 43–41 over Westmont Hilltop. Ill and spent, Tommie had accounted for more than half of the Quips' points.

Now what? More than ever, that is the Aliquippa question. A company town without a company, down to a population of 9,317, is like a man past his prime; both become hollowed, age faster, without the regenerating charge of daily purpose. "Aliquippa's in a weird place: It's not the center of the region, it's not the city, it's not quite rural," said University of Pittsburgh labor professor Chris Briem. "What is the competitiveness of a lot of towns that used to have a reason for being and don't anymore?"

Ditka's heirs, meanwhile, have scattered. Unlike Iron Mike, they left Aliquippa unburdened by golden-age memories; the town gave them toughness and fuel, they know, but ultimately it was a place to escape. Sean Gilbert lives in North Carolina, Darrelle Revis in New Jersey during the NFL season and Florida in the off-season. They return to Aliquippa on the odd weekend to see family, to show that they haven't forgotten their roots, to give kids a chance to see a local boy who made good.

All have tried giving back. Gilbert started a nonprofit counseling program and the construction of a Plan 11 church, which was never finished; Ty Law funded a Head Start program in Plan 12 and ran a charity golf tournament and basketball game to raise cash for school supplies and computers; Revis holds an occasional football camp and has funneled NFL-style Nike uniforms to the Quips program. But all are wary of pleas to refurbish the Pit or simply drop masses of money on the town because no one knows whether Aliquippa High will even exist in five years. And then there is the largest unspoken question: How much, really, do I owe this place?

Years ago Law was stopped by an elderly lady. "What are you going to do for us here in Aliquippa, Mr. Law?" she said.

If he had known the woman, he might have lit into her. "You look at it," Law said later. "There wasn't nobody out there running with me at midnight, there wasn't nobody dealing with what I was dealing with at home. So I don't owe you anything. I owe my grandfather. I owe my mom. Because if I was out there selling drugs and end up going to jail, what are you going to do? You going to come bail me out?

"Unfortunately that's the mentality for some because a select few of us made it. Even if we put all our money together, we cannot change the facts. We can probably fix up a hundred homes to where they look real nice and pristine. But that's not going to change the environment with the drugs and the fact that there ain't no jobs. How you going to maintain it? It's going to get right back like it was before we fixed it up."

They always speak of the Next One in Aliquippa, but the position also casts a shadow. Because for every Quips alum like Law there's a gun-toting wraith, like Monroe Weekley, whose talent isn't enough to stop him from killing or being killed, fast or slow: the Next Waste. Weekley, the star linebacker of the class of 2001, is now in jail for murder. And by '08, Tommie Campbell had just about completed his jump from One to the other.

Of all of the great athletes on that '03 state championship team, Tommie might have been the most gifted. But he flunked out of Pitt, lost a full scholarship after two years of missed classes, practices and football meetings. His last-chance meeting with coach Dave Wannstedt? Campbell didn't show; didn't even call. He had narcolepsy, tended to skip his medication and never saw why the world couldn't soften up its pesky rules, schedules, commitments. "Like a lost little boy," he said. "I never had a plan. I just thought things were going to be handed to me."

Such entitlement was rarely discussed on the Next One side of the divide. If football presented Aliquippa's flashiest alternative to drug dealing and led to scholarships, too often its players went off ill-prepared and returned without a diploma—never mind a pro contract. And, paradoxically, successes like Ty Law's could discourage those bumping up against the limits of their own skill or desire. Once a means to escape the steelworker's fate, a bargaining chip for that so-coveted college diploma, football had evolved into an end in itself, a promise of riches and fame that made a mere bachelor's degree seem shabby.

"Some of our guys have been struggling," former school district superintendent Dave Wytiaz said. "Everybody can't play at Pitt, Penn State, Notre Dame, but you may be able to play at Grove City or Westminster. But they go to these places, and it's a step down athletically—and they can't handle it. The kids are bright enough. There's nothing wrong with going to Slippery Rock or Indiana University of Pennsylvania. Get your education."

Still, if it doesn't work out, Aliquippa and its troubles always welcome them home. After sleepwalking his way out of Pitt, Tommie Campbell played the '07 season at Division II Edinboro (Pa.) University and then washed out of there too, all the way back to his mother's couch in Aliquippa. He started smoking, drinking, dropped 25 pounds, frittered away a year on PlayStation. One night he rushed in, shaken from a run up to Valley Terrace. "He was over some girl's house," said his mother, Della Rae. "They thought Tommie had money and wanted to stick him up because he was delivering. They put the gun to his head and it jammed. Tommie had tears coming down his face. He just knew that was going to be his last thing, right there."

Campbell won't confirm those details, but he admitted, "It was a real scary moment, man. If that had never happened to me, I probably wouldn't be where I am today. I got scared straight."

No. Fear was only half the antidote. Next came shame: Tommie was 22, with two sons, no future, no job. He tried to enlist in the Marines, but $2,000 worth of unpaid speeding tickets ended that. He stayed on the couch, scared to go out and face people asking what the hell he was doing with his life. A girlfriend's connection finally landed Campbell one of the few positions for which he was qualified: janitor, at Pittsburgh International Airport's USAir terminal. For six months he worked the graveyard shift, changing can liners, scraping gum off the floors, spraying blue chemicals into filthy toilets. Every two weeks he took home about $460.

Every day men and women hurried past him without a second look, on their way to homes, careers, respect. You'd think Campbell's worst nightmare would be the sight of a pro football player walking past. "I saw something worse: one of my ex-teammates from the University of Pittsburgh," Campbell said. He was pushing his cleaning cart in the terminal when he saw defensive back Elijah Fields approaching in his team-issued sweats. Campbell wanted to disappear. Fields saw him.

"It made me feel little," Campbell said. "I told him I was proud for him because he was doing the right thing at the time. I told him, 'Listen, if you don't take care of what you need to take care of, you're going to be right here too.'"

Fields didn't listen. By 2010 he had been kicked out of Pitt in a haze of indolence and pot smoke. But the chance meeting lingered with Campbell. "There's a lot of time to think while you're mopping that floor," he said. "Lot of time to think about what you could've done better—and if you ever get a chance again, what're you going to do?"

Finally Campbell reached out to Larry Dorsch, a white real estate developer living in whiter, quieter Cranberry Township, whom he'd met just before going to Pitt. Dorsch put him to work on one of his job sites, gave him money to eat. But Dorsch also invited Campbell to move in with him, his wife and her 83-year-old mother. Della didn't like it; she wanted her son to stay home. But Tommie knew this was his last chance.

He stayed there a year and a half. The Dorsches laughed when their neighbors did double takes at seeing a young black man come and go. They started calling Tommie the Fresh Prince of Cranberry. He called Dorsch Pops. "He helped me in every aspect possible," Tommie said.

The cigarettes disappeared. The first time Campbell tried a timed 40-yard dash he ran a 4.70—good for bragging at the Hollywood Lounge and little else. Then the meals and sleep and work kicked in, and the pounds began to stick. Campbell paid off the speeding tickets. He persuaded a skeptical defensive coordinator at California (Pa.) University to give him a shot. Everybody in western Pennsylvania knew what a motivated Tommie Campbell, back up to 220 pounds now, could do.

Campbell turned 23 during the 2010 season—his final year of college eligibility—in which he played cornerback for the Vulcans. He started four games, appeared in all 12, finished with 29 tackles. He showed up for meetings. He did not oversleep. He made sure to take his medication. "I quit putting blame on everything around me," Campbell said. "You have a choice to get up in the morning or not, to work out or not, to go to class or not. You're reflected by the choices you make, and I was making no choices at all—by sleeping."

But at Cal U and beyond, Campbell wanted to run again. He went to the Cactus Bowl All-Star Game, lit up NFL scouts' eyes and stopwatches with his 40-yard times of 4.33 and 4.31. Suddenly his past and age didn't matter. The Titans drafted him No. 251, the fourth-to-last pick in 2011. A 90-yard game-winning interception for a touchdown against the Bears in preseason sealed his rise. He signed a four-year, $2.1 million contract. He'd made the league at last.

Campbell played three years in Tennessee and another in Jacksonville, mostly on special teams and as a backup defensive back, countering niggling injuries with preseason heroics—an 84-yard kick return here, a 65-yard punt return there. He was never a starter, but he became a steady, tough, fully awake professional. That's more than most can say.

When he walks through an airport these days, Campbell carries a fine bag, and the clothes inside are expensive and clean. He eyes the men pushing carts, the men with short brooms and dustpans. He may not say a word, but when he stops at a urinal and sees the blue water, it comes back: Tommie can smell his past. He used to be so careless with trash, leaving cups and wrappers where they'd fallen. Now, no matter how long it takes, he leaves no trace of himself behind.

Ty Law, a 2016 semifinalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, lives in Rhode Island and owns a chain of indoor trampoline parks. Tommie Campbell is a starting defensive back for the Calgary Stampeders, who at week's end were leading the West Division of the Canadian Football League.