The NFL Head Coaching Fraternity Is Getting Less Diverse. Here’s Why

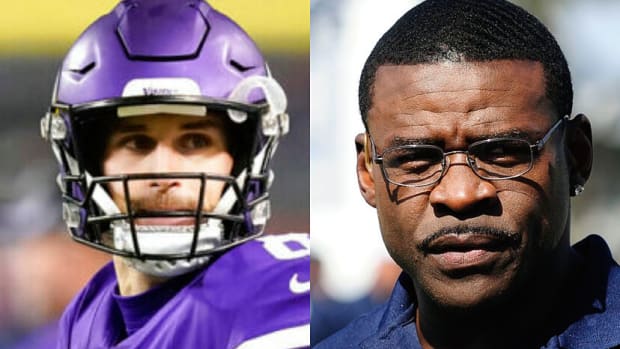

Let’s start with some facts. The 2018 firings left just two of the NFL’s 32 teams with African-American head coaches, in a league in which the players are better than 70% African-American. This latest wave of hirings has done nothing to ameliorate that disparity; the league’s head coaching fraternity has gotten far less diverse. Of the eight newly hired or presumptive head coaches, one, Brian Flores, who’s in line for the job in Miami, is black. Two coaches are recycled—Bruce Arians in Tampa and Adam Gase with the Jets. In addition to Flores, first-timers include Vic Fangio (Denver), Freddie Kitchens (Cleveland), Kliff Kingsbury (Arizona), Matt LaFleur (Green Bay), and Zac Taylor, the presumed candidate in Cincinnati. In this year’s process, the ineffectiveness of the Rooney Rule—which requires that all teams interview at least one minority candidate before making their hiring choices—was laid bare once and for all.

But instead of focusing on who the newcomers are not, it may be more instructive to examine who they are.

In 2016, I wrote about that year’s rookie class of quarterbacks, a predominantly white group of young men who, through special talent and hard work, ascended to the 1% of the most difficult and important position in the game.

What made them who there were? Turns out they had a lot in common. They were mostly sons from two-parent homes, with strong parental advocates who guided their amateur careers with ample resources and a depth of knowledge about the challenges ahead. They were from affluent families, with few exceptions, and they carried themselves with confidence and a sense of responsibility unmistakable in successful quarterbacks. They were invested in themselves, and perhaps as important, they’d been invested in—by the elaborate framework of advocates and resources surrounding them. It was no mistake that they were NFL quarterbacks. There was perhaps one Cinderella story in the bunch; the rest were bred to be where they were.

JONES:The Cardinals’ coaching search went fast—too fast

These new head coaches have a lot in common with our quarterbacks.

Take new Cardinals coach Kliff Kingsbury, 39, who played football for his father at New Braunfels High in Texas. His late mother retired from teaching, only to rejoin the high school so her schedule matched with her sons. Kliff played quarterback.

Throw in Browns coach Freddie Kitchens, 44, whose father, Freddie Kitchens, Sr., was a Gadsden, Ala., youth coach. Freddie Jr. played football for Freddie Sr. as a boy, and Senior had the means to ferry Junior to and from practice and games for numerous youth baseball teams, too. Freddie played quarterback.

Then there’s new Packers coach Matt LaFleur, 39, son of Denny and Kristi LaFleur. His father was a standout linebacker at Central Michigan, and later, linebackers coach at the school. Matt would get his coaching start as a graduate assistant there in 2004, years after the retirement of his father, who maintained close ties to the program. LaFleur, of course, played quarterback, as did his brother, now an assistant with the 49ers.

As for presumed Bengals head coach Zac Taylor, currently the Rams’ quarterbacks, coach, he played quarterback at Nebraska and got his start in coaching as an assistant under his father-in-law, Mike Sherman, at Texas A&M. Here’s my colleague, Andy Benoit, on the Taylor family:

The Taylors grew up in Norman, Okla., on a cul-de-sac in the type of neighborhood you see in a 1990s Americana family sitcom. More than 20 kids lived nearby. A neighbor had a big square yard, and the touch football games were epic. “Everyone in Norman knew our block,” Zac says. “There were five kids in our neighborhood who started at QB in high school. We had Division-I athletes from a number of sports available to play at any moment.”

The Taylors’ dad, Sherwood, played football for Barry Switzer at Oklahoma in the 1970s and coached briefly for the Sooners and Kansas State Wildcats in the early ’80s. “He was always the most physical when we played sports, not afraid to elbow an eighth grader,” Zac says. Besides Zac and Press, Sherwood and their mother, Julie, had two daughters. It was a close-knit family with strong traditional values.

The exception to this group, Brian Flores, is an all-too-rare example of a young, African-American coach leapfrogging more experienced candidates on the way to a top gig. He's been propelled not by quarterback expertise or pedigree upon entry to the NFL, but through a 15-year long alliance with Bill Belichick, the most successful head coach in NFL history and one of football history’s renowned defensive minds.

VRENTAS:Adam Gase’s biggest reason for taking the Jets job? Developing Sam Darnold

To be clear: There’s nothing wrong with what the Kingsbury, LaFleur, Taylor and Kitchens families have accomplished.

Parents should strive to make lives better for their sons and daughters. The greatest and most successful American families are built on sacrifice and experience, and it’s no coincidence that the majority of successful NFL coaches got head starts from their dads.

But let’s not pretend this is a meritocracy. The journey of the most elite football coaches mostly mirrors that of the most elite quarterbacks. There’s an exceedingly narrow path to becoming an NFL head coach at a young age, as Kingsbury, Kitchens and LaFleur have done, and the first step on the drawbridge—the prerequisite—is privilege. That necessarily leaves a number of boys, white and black, on the outside looking in. At an immediate deficit are those from single-parent homes, those whose fathers aren’t coaches, those who aren’t surrounded by advocates and resources and examples of professional success in close proximity.

As a result, the game suffers. When the pool of candidates in any field is narrowed by pedigree, connections and nepotism, many of the best potential candidates are never seeing the light of day.

The statistics tell us the boys in this group are disproportionately children of color, and the history tells us that America’s legacy of chattel slavery, Jim Crow, the War on Drugs, and every other manifestation of systemic oppression of African-Americans in this country is a direct influence on the station of the typical black child in America.

KLEMKO:How NFL quarterbacks are made—the demographics of a successful QB

This is only part of the problem, of course. The argument can be made that white coaches may appeal more to predominantly white decision-makers, whether those decisions are conscious or unconscious, the result of intentional racial bias or bias unknown to the boss himself. An equally compelling argument could be made that black coaching candidates are held to higher standards than white candidates.

But the problem of under-representation among NFL head coaches, at its root, begins much earlier. It begins with socioeconomic disparities deeply rooted in this nation’s sad, exploitative history. It’s about our collective willingness to ignore that history, and to be satisfied with programs and policies meant to curb racial inequality, which in reality amount to nothing more than Band-Aids on gunshot wounds. It’s about the way black, football-loving boys grow up in comparison to the men they end up playing and working for in pro football.

Question or comment? Email us at talkback@themmqb.com.