As NHL enforcers fade, tough guys will always be needed

Four decades ago, the NHL team that calls Philadelphia its home was not known as the Flyers. That may have been the name listed in the program, but fans knew better. Those brutish icemen were the Broad Street Bullies, and nobody better exemplified their feisty ethos than winger Dave Schultz. In 1974–75, the Hammer scored all of nine goals while earning 472 penalty minutes, still the NHL single-season record.

Today players like Schultz are dinosaurs. The tough guys known as enforcers—only the least skilled among them are called goons—are fast disappearing from the NHL. During the past 10 years, fighting has decreased dramatically from 789 bouts in 1,230 regular season games (41.14% of all matches had at least one fight) in 2003-04 (the last full season before the lockout that cost the NHL all of 2004-05) to 469 in the same number of games last season (29.76%).

The reasons for this are many, though a general push for safety is foremost among them.

SI.com's 50 landmark hockey fights

, 35.

The deaths shined the spotlight on the possible dangers of the life of an enforcer, including concussions. Within the past two years, the NHL has been hit by two lawsuits, one with more than 200 former players as plaintiffs. Both suits claim that the league has not done enough to address head injuries.

GALLERY: Notorious Enforcers and Goons

Notorious Enforcers and Goons

Stu Grimson

Ever since the NHL's early days when Montreal's Sprague Cleghorn terrorized the ice, the league has housed pugnacious souls whose primary function is protecting their more skilled teammates by intimidating opponents into steering clear, and delivering swift and terrible fistic punishment upon transgressors. One such character was Grimson, Detroit's 10th round pick in 1983. The Grim Reaper stalked the ice for eight teams, accumulating 17 goals and 2,113 penalty minutes.

Dave "The Hammer" Schultz

The quintessential Broad Street Bully is best known for beating the feathers out of hapless Rangers defensemen Dale Rolfe in a 1974 playoff game. The Hammer set the single-season mark of 472 penalty minutes during the Flyers' second straight Stanley Cup campaign (1974-75).

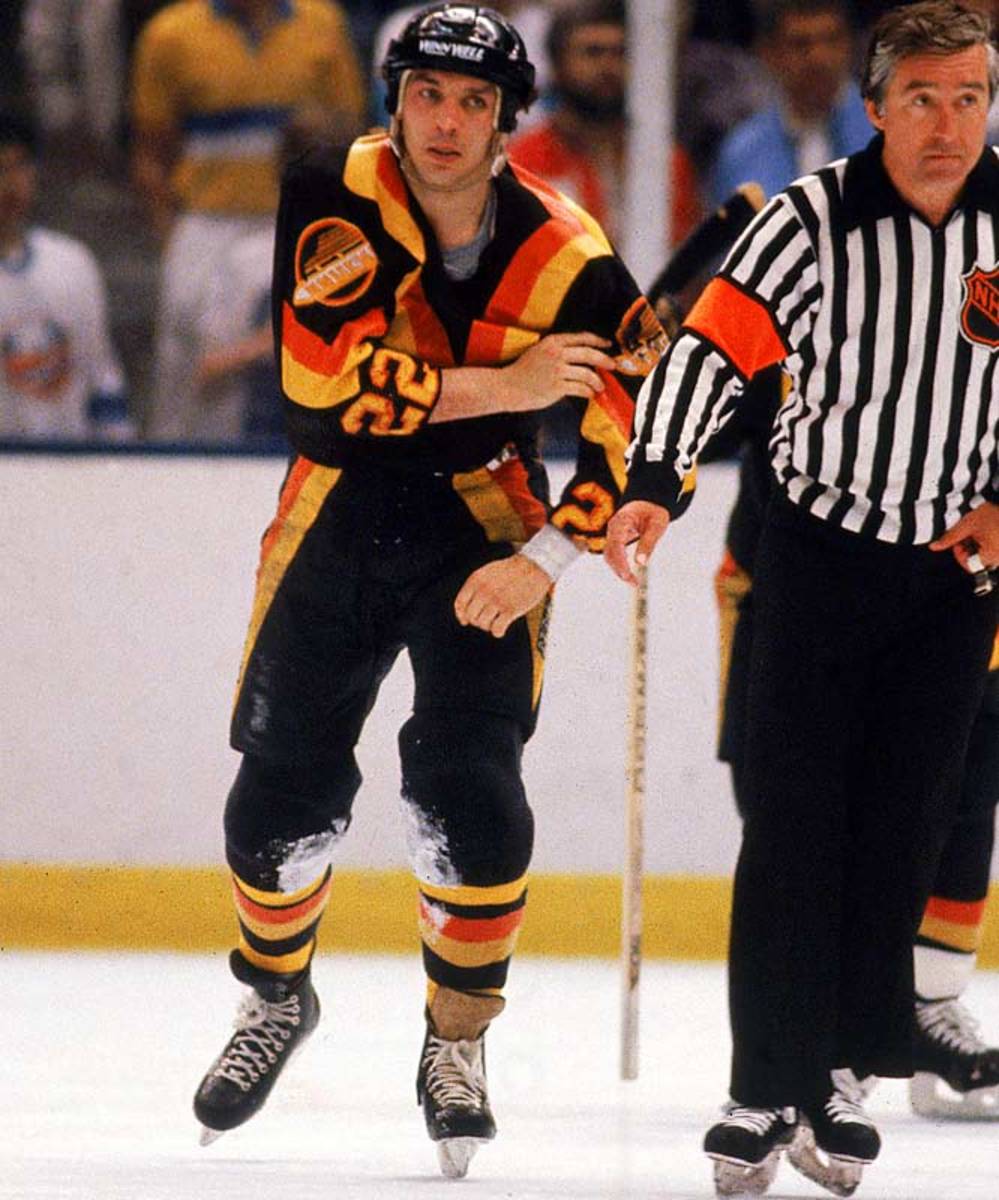

Dave "Tiger" Williams

No one spent more time in the sin bin than the ferocious Tiger -- a grand total of 4,421 minutes (including playoffs), the equivalent of a little more than three days.

Tony Twist

The Blues' ninth-round pick in 1988, The Twister was unafraid of any opponent. He even took on the creators of the Spawn comic book series over their use of the name Anthony "Tony Twist" Twistelli for a mob enforcer and won a $15 million court settlement.

Tie Domi

A fan favorite in Toronto, New York and Winnipeg, the relatively diminutive Domi (5' 10", 213) battled all comers. Inspired by his childhood hero Tiger Williams, Tie racked up 1.020 PIM (third all-time) and ably rode shotgun for Maple Leaf stars Doug Gilmour and Mats Sundin.

Bob Probert

A bad boy on and off the ice, he was one half of the Detroit's feared Bruise Brothers (with Joey Kocur), watching Steve Yzerman's back and keeping his gloves on long enough to become an All-Star in 1987-88. He also plied his rough trade in Chicago.

Joey Kocur

The other half of Detroit's Bruise Brothers actually led the NHL in PIM (377) in 1985-86 while skating with feared enforcer Bob Probert and the equally ungentle Randy Ladouceur. Kocur later mixed it up for the Rangers and Canucks.

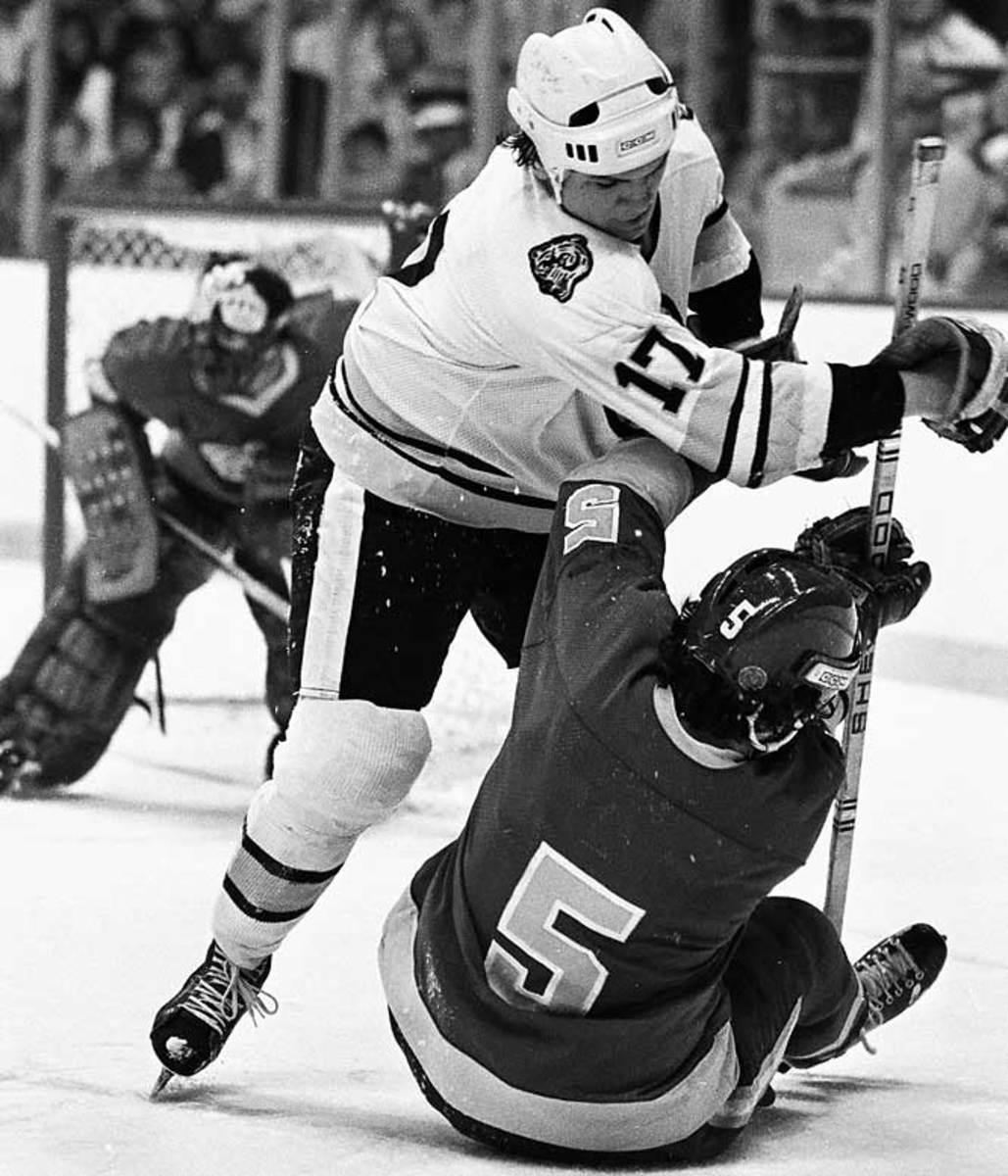

Marty McSorley

Marty Mac (bottom) had Wayne Gretzky's back in L.A., succeeding Dave "Cement Head" Semenko, the Great One's protector in Edmonton. With Boston, McSorley got himself charged with assault and suspended indefinitely for applying a stick to the head of Vancouver enforcer Donald Brashear in a 2000 game.

Chris Nilan

About as subtle as a flying mallet, Knuckles Nilan racked up a record 10 penalties (six minors, two majors, 10-minute misconduct, game misconduct) in one memorable tilt against Hartford in 1991. He had two stints with Montreal and threw punches for the Bruins and Rangers. He was also the subject of the 2011 film about enforcers called <italics>The Last Gladiators</italics>.

Rob Ray

Buffalo's eighth-rounder in '88 was as cagey as he was feisty -- a master at peeling off his sweater and equipment so opponents had little to grab. The NHL was moved to hit "The Rayzor" with equipment rules violations.

Georges Laraque

At 6'8", 243, <italics>The Hockey News</italics>' Best Fighter of 2003 is still going strong in Phoenix, as his decisive victory in a 2006 heavyweight bout with Minnesota masher Derek Boogaard clearly demonstrated. Laraque retired with 1,126 PIM.

Derek Boogaard

At 6-7, 250, the brutal Boogeyman was no one to dance with, but he paid a terrible price for his role as a fighter. Addicted to the painkillers he used to play through his injuries, he died of an overdose at age 28.

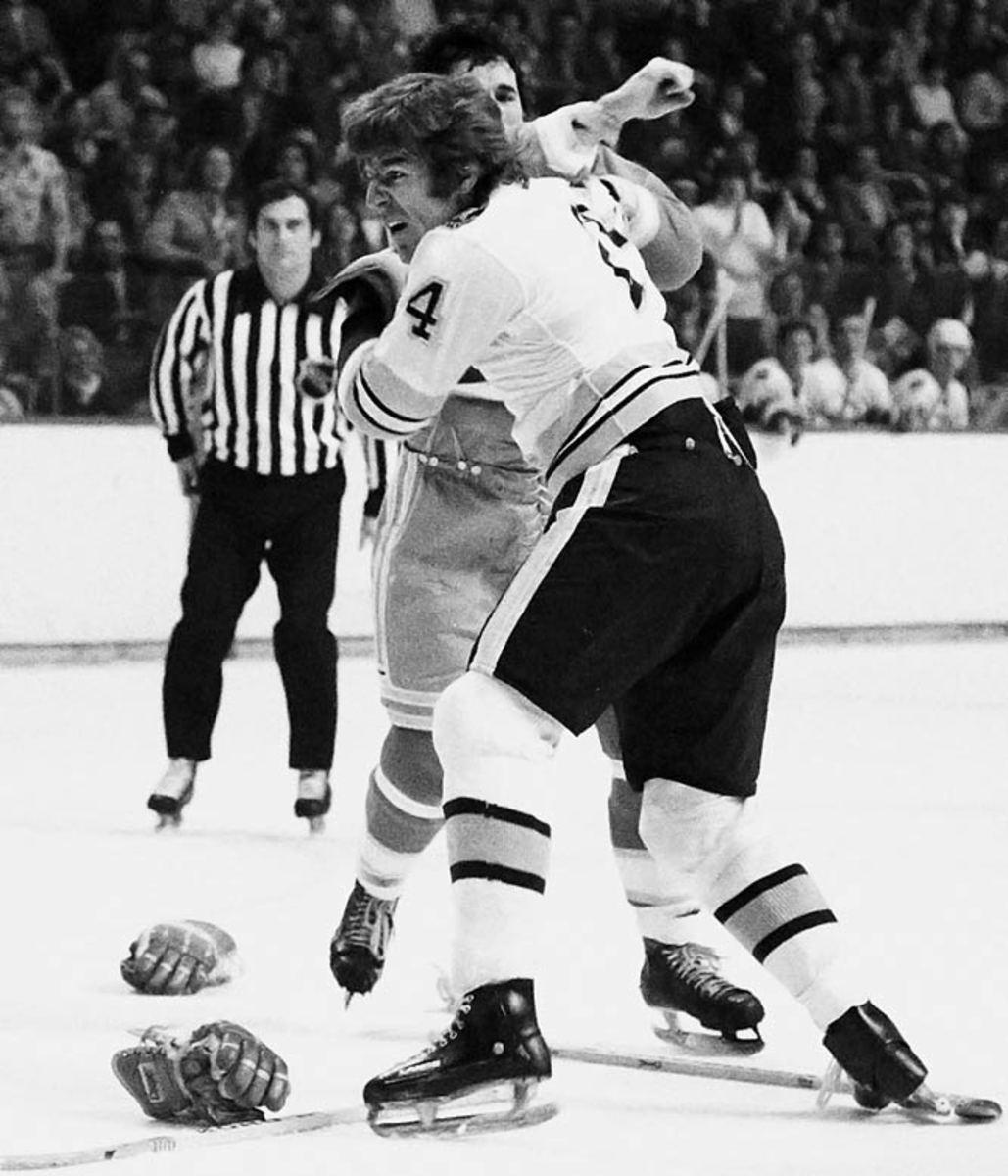

Stan Jonathan

A diminutive (5-8, 175-pound) wrecking ball, Jonathan was a favorite of coach Don Cherry and Bruins fans for six seasons (1976-82). He was a fearless checker and hellacious fighter, often taking on such heavyweights as Dave Schultz and Moose Dupont, and winning. His most hair-raising bout was against Montreal's Pierre Bouchard on May 21, 1978. The link below is not for the faint of heart.

Terry O'Reilly

A teammate of Stan Jonathan and charter member of the Big Bad Bruins of the `70s and early 80s, O'Reilly was turbocharged power forward with a cerebral streak (he often kept his nose buried in books) who nevertheless earned coach Don Cherry's ultimate kudo: "He's tough, really tough, and that's the way I like em'." O'Reilly's bouts with Clark Gillies and Behn Wilson are considered classics.

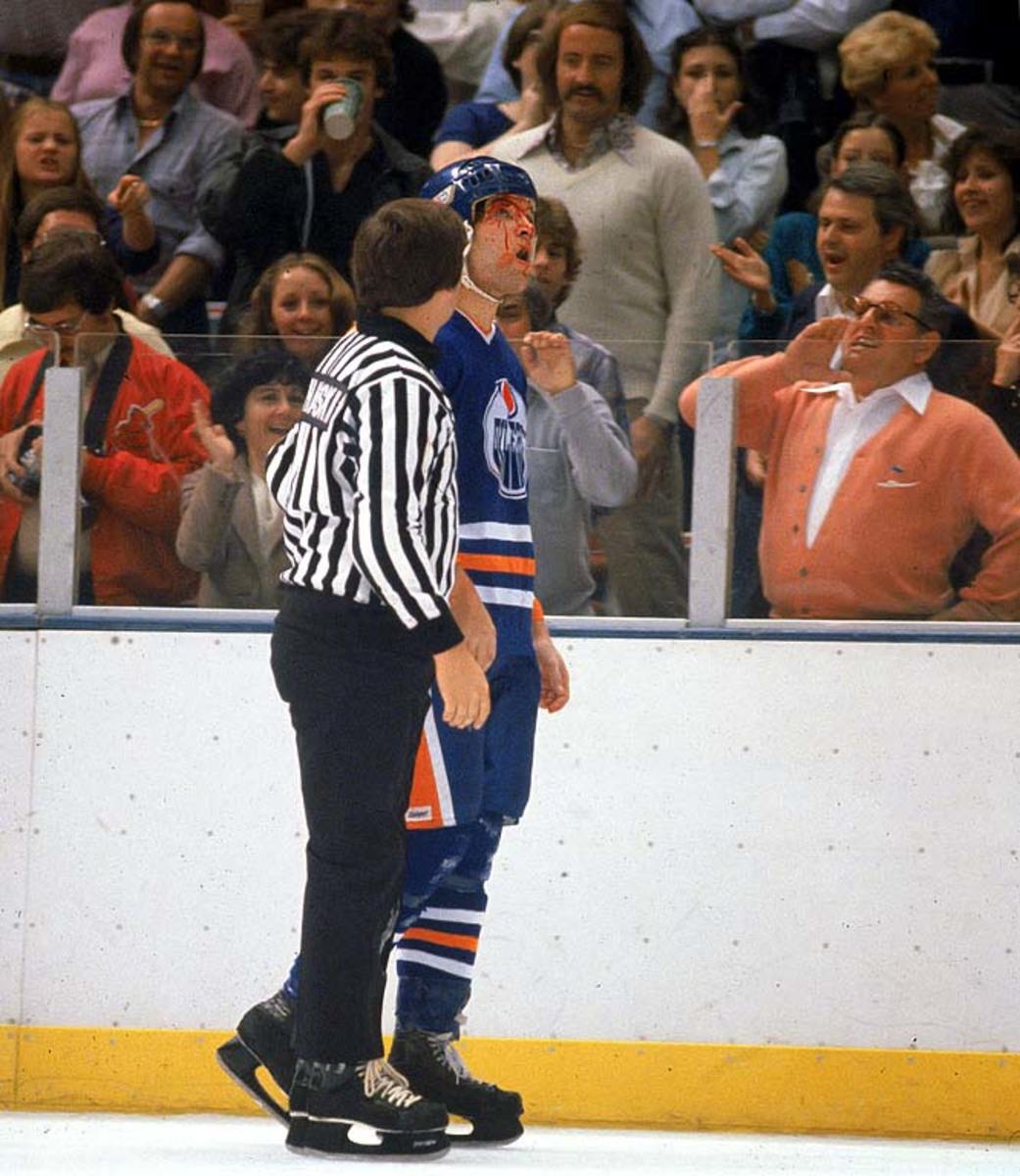

Dave Semenko

The aptly nicknamed "Cement Head" was Wayne Gretzky's bodyguard on the dynastic Oilers of the 1980s and often cited as one the key reasons the Great One could roam untouched and wreak such havoc. The strapping Semenko did his part by parking his carcass in front of the net or dismantling any and all who dared touch No. 99. Teammate Kevin Lowe saluted Semenko by calling him "the Gretzky of the tough guys."

Dave Brown

A classic Flyers bully, Brown roamed the ice for Philly, through the 1980s and again in the 90s after a stop in Edmonton, making life very unpleasant for anyone who took liberties with his teammates. A ferocious puncher, the 6-5, 220-pound winger was so feared that sometimes only a glance, a word or a tap on the shoulder from him would be enough to send a foe scurrying for safety.

Riley Cote

A prominent member of a new generation of Flyers assailants, the 6-2, 216-pound winger seemed programmed for mayhem in a way that suggested an almost cyborg-like mindset. As one foe observed to SI.com's Michael Farber, "Cote doesn't even know there's a puck on the ice."

George Parros

One of the more unusual members of the hellbent-for-leather set, the mustachioed Parros is an urbane gentleman with an economics degree from Princeton. He's mainly been putting it to good use by economically pounding the feathers out of opponents for the Kings, Avalanche, Ducks, and Panthers before being dealt to the Canadiens in July 2013.

Matthew Barnaby

One of the game's great yappers and disturbers, the 6-foot, 188-pound Barnaby would fearlessly concede 50 pounds or more to his opponents. He was beloved by the fans of seven teams for his heart and scrappiness.

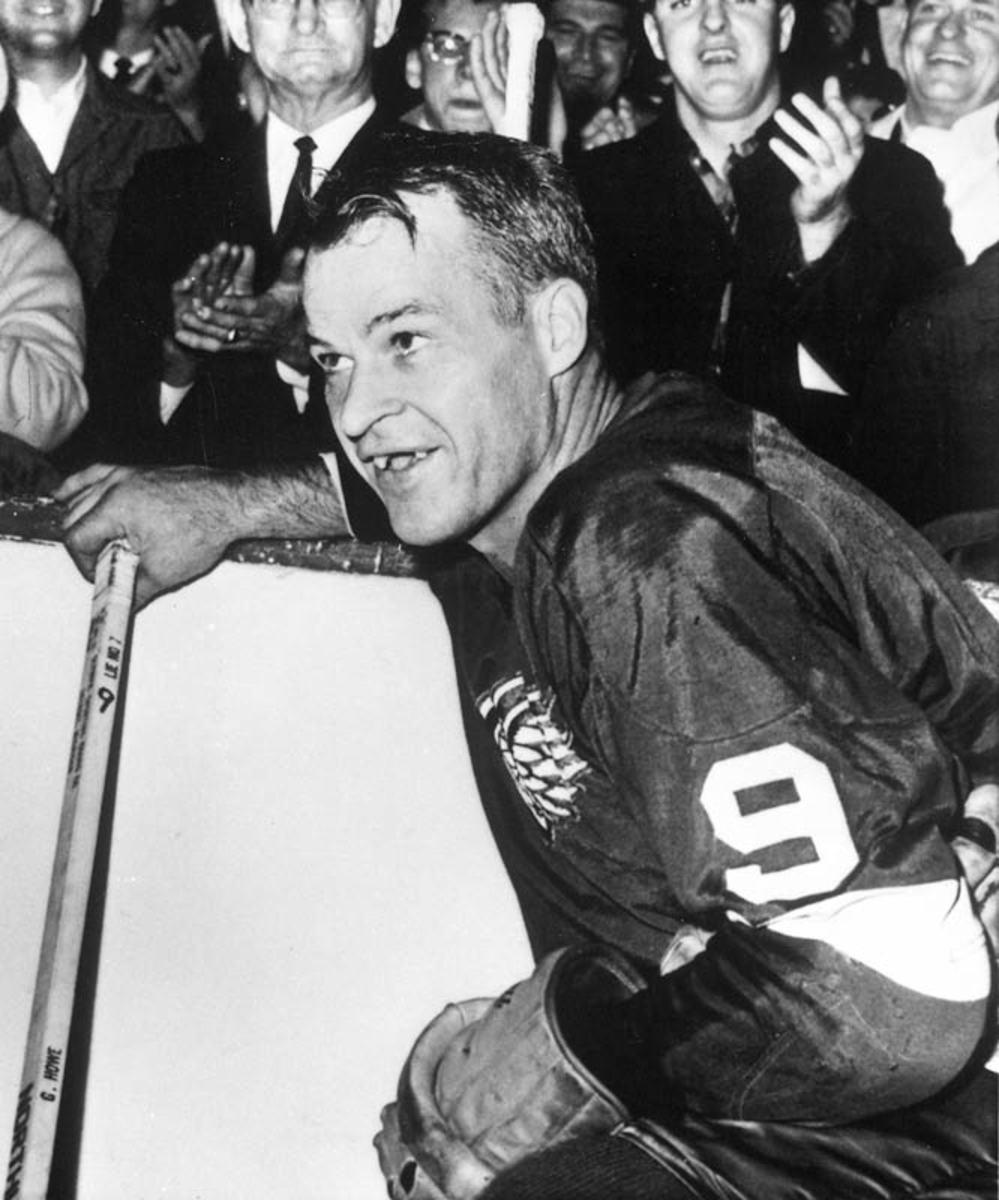

Gordie Howe

The legendary Mister Hockey may be beloved, but he was as nasty as they come in the corners and with the gloves off. He set the tone during his rookie season, knocking out Montreal's equally-tough Rocket Richard with one punch. Howe's greatest bout may be his battering of Rangers' tough guy Lou Fontinato into a pulp at Madison Square Garden in 1958. His blows were described as sounding like an axe splitting wood, and "a Gordie Howe Hat Trick" is a classic hockey term for having a goal, an assist and a fight in the same game.

Concussions played a large role in the premature retirements of such All-Star players as Eric Lindros, Pat LaFontaine, and Keith Primeau. And head injuries have threatened the career of the Penguins’ Sidney Crosby, who last season won the second NHL scoring title of his nine-year career. Since early 2011, he has missed significant playing time while recovering from concussion-related symptoms. The loss of the game’s brightest star was enough to prompt the league to act.

Last year, the league made helmet visors mandatory for all new players, and made it a minor penalty for a player to remove his helmet during a fight. Who wants to punch a piece of hard plastic? “Rules changes are always going to favor the guys who score goals,” said Donald Brashear, who spent 17 seasons in the league and in 2010 was named enforcer of the decade by the Hockey News. “The rules are never going to be made in favor of the guys who make body checks.” Or drop the gloves.

With fighting under fire and concern about head injuries at an all-time high, enforcers such as George Parros (159 fights over nine seasons, according to Hockeyfights.com), Zenon Konopka (112 in nine), Arron Asham (98 in 15), Mike Rupp (81 in 12), Krys Barch (112 in eight) and Kevin Westgarth (32 in five) are now out of work. Teams seem reluctant to carry a fourth-line player whose only prominent contribution to victory is fisticuffs.

“The way the game is played has changed, and coaches nowadays want players who are able to do more than just drop their gloves,” says Hall of Famer Cam Neely, the president of the Bruins. “If you look at what we had in Shawn Thornton for a number of years, he played a good role on our fourth line. You could look at him as an enforcer, but he also played decent minutes.”

After two straight seasons in which Thornton did not reach double figures in points—but he did hit double figures in fights—Boston dropped the winger during the off-season. On the first day of free agency in July, the Panthers signed the 37-year-old Thornton. A tough guy who can play a little is still in demand.

It’s not like the Bruins will be defenseless this year. They began the season on October 8 with their tough-guy role being filled by Bobby Robins, a 32-year-old rookie and career minor leaguer who had 687 penalty minutes (and just 11 goals) during the last three seasons with the AHL’s Providence Bruins. In Boston’s season opener against the Flyers, the 6' 1", 220-pound winger drew a charging penalty with a teeth-rattling hit on ZacRinaldo. When Philadelphia tough guy Luke Schenn came to his teammate’s defense, Robins fought him, to the delight of the crowd at TD Garden. But his stay with the team was brief. On Oct. 14, the Bruins sent Robins back to Providence.

Despite the presence of an apparent goon on his roster, Neely insists that he'd really rather have a tough guy who can do at least a few things on the ice besides throw punches. “Rather than having an individual in that enforcer role, we talk about team toughness,” he says. “That means taking a hit to make a play, and taking the body when the body is there to be taken. It’s not necessarily about putting the guy in the sixth row, just taking him out of the play, within the rules. The intimidation factor isn’t going away.”

Neely does not want fighting to disappear altogether. Lightning general manager Steve Yzerman and Penguins GM Jim Rutherford have advocated for fighting majors to be toughened to game misconducts. And during the Bruins–Flyers pregame segment on NBC, analyst Mike Milbury—while acknowledging that during his playing days he “liked a good scrap”—called for the elimination of fighting from the game. “Let’s grow up,” he said, “and get rid of it.” Neely, on the other hand, takes a stance more in keeping with the tough-guy-with-a-scorer’s-touch attitude he brought to the ice in his 13-season NHL career, during which he had 79 fighting majors to go with 395 goals. (Yzerman, a fellow Hall of Famer, had nine fights in 20 seasons. Rutherford was a goaltender and never fought.)

“There’s constant conversation within the league about us doing what we can for player safety,” says Neely. “But things happen on the ice, organically, that lead to guys getting into it with each other. Tempers flare. For me, it was always, ‘Hey, he did something to piss me off, so let’s settle this now.’ I don’t see that going away anytime soon, because of the nature of the sport. Hockey is a physical game.”