Patrick Roy: the modern NHL’s most influential player?

Dominate for long enough in the NHL and a player's name gains ascendancy in discussions of who was the best ever at a given position as well as Hall of Fame enshrinement. Dominate so distinctly as to change how the game itself is played, and one enters into a whole other conversational arena where ideas are bandied about on how hockey should best be played.

Bobby Orr does very well in these talks, building as he did on Doug Harvey's two-way legacy by dynamically making defense as relevant at the offensive end of the ice as the defensive. Orr brought an unprecedented flow to the game, which opened the way for a host of similar, if lesser, talents to follow. Wayne Gretzky later opened the offensive zone in ways endemic to him, which allowed everyone—like Paul Coffey, a defenseman in name only—to get in on the fun.

Prime time: Ray Bourque's career may have topped Orr's

Other players like forward Bob Gainey reconfigured what you’d consider the possibilities of the position, or, more specifically, the expectations of the position. Gainey wouldn’t give you much offense, but he played such a consistently superb role in disrupting the other team’s attack that he received the Selke Trophy in each of the award's first four years of existence, thereby establishing himself as the standard by which two-way forwards were judged.

But there is no player who has had the impact on hockey like Patrick Roy has during the last three decades. If you watch any game, on any night, you will see Roy hallmarks more than any you might associate with Orr or Gretzky, and it is not even close.

For the simple reason that Roy, you might say, brought modern goalies to their knees. In a good way. From an efficacy standpoint. Aesthetically—well, there might be some grumbling there.

Even though Roy is cited, regularly, as one of the three or four best goalies to ever play—and it’s not tough to make an argument for him in the number one spot—we tend to forget how choppy his early career was. Which is ironic, given the flash of brilliance that colored the postseason of his rookie campaign with Montreal in 1985-86.

Those Canadiens finished second in their division at 40-33-7. They got a big season from winger Mats Naslund(110 points), a surprising one from forward Bobby Smith (31 goals, 86 points), and a resurgent one from blueline stalwart Larry Robinson. They were by no means a high-flying team, despite this being the zenith of the high-flying era, with Gretzky registering 215 points. They were a defense-first team with a 20-year-old starting netminder in Roy. The less than immortal Doug Soetaert was one back-up, the other was Steve Penney, possessor of one of those wonderfully odd hockey careers that makes some people fondly nostalgic when they recall it, others madly frustrated.

Two seasons prior, Penney went on a classic series-stealing run in the playoffs after having played a total of four NHL regular season games in his career. All of which, incidentally, he had lost. During the following campaign he was a Vezina Trophy contender, but come 1985-86 he had lost it completely, with a GAA of 4.36 and a save percentage—are you ready for this?—under .840.

What Brett Hull’s 86-goal season teaches us about today’s NHL game

Enter, then, Roy. The Bruins had a down year, their scoring leader being Keith Crowder (the one season of his 10-year career in which he averaged more than a point per game), and the Canadiens, it seemed, always beat Boston, so the opening round was no great surprise, with Le Bleu-Blanc-Rouge advancing easily.

Then the Canadiens knocked off a plucky Hartford team in seven. It was a Whalers squad that had Mike Liut—a borderline Hall of Fame guy himself—on one of those matchless, or near matchless, runs of his, and let it be said that few goalies could get hotter than Liut. Still he was no match for Roy.

The New York Rangers were a weak conference final foe, but the Calgary Flames, in the Stanley Cup Final, were furnace-fire hardened by then. They had vanquished the mighty Oilers, for one thing (and had come damn close to doing so in 1983-84, when the Oilers finally ran out the Islanders, one of the two or three top teams in NHL history), and were becoming one of those clubs that could beat you any which way you cared to play.

Roy and the Canadiens needed all of five games to claim the Cup. Roy, who had finished fifth in Calder Trophy voting that year—meaning, he was fine, not great—won the Conn Smythe with a postseason that will always number among the best: a 15-5 record, 1.92 GAA, .923 save percentage.

The SI Extra Newsletter Get the best of Sports Illustrated delivered right to your inbox

Subscribe

Montreal fans, stoked that they had their first Cup since 1979, must have wondered, though, if Roy would be more like Steve Penney or Ken Dryden, the latter of whom had pulled off the remarkable feat of winning the Smythe in 71 and then the Calder for 1971-72. Who on earth wins a major award before their rookie year, right?

Dryden was a stand-up goalie, for the most part, unlike his teammate on the 1972 Summit Series squad, Tony Esposito, or Espo's counterpart, Soviet netminder Vladislav Tretiak who became an international star and influence in Canada with his performance at that historic tournament. It was Esposito, Tretiak and Roger Crozier who began to bring into vogue the butterfly style that greats such as Glenn Hall and Jacques Plante (though he later warned against it) had pioneered. If you watch tape of those keepers now, you see they were hybrids who spent a fair amount of time on their feet. Roy made the butterfly his game, times ten.

Roy's game is now essentially the game of every goalie in the league, and if you want to score, you better love yourself some deflections, some dirty goals, rebounds and scrambles, and have a knack for putting the puck just under the bar, because shots have a hard time gaining sweet ingress otherwise. Goalies, the criticism goes, don’t make saves any more, they let the puck hit them. And they’re better at that than ever.

It’s a reasonable point, from a standpoint of artistry, but then again, it’s also reasonable to think that if you can play a position in the most effective manner, you learn to do so. And a lot of NHL people—coaches as well as keepers—learned with Roy, starting during his 1985-86 run.

GALLERY: SI's Best Photos of Patrick Roy

SI's Best Photos of Patrick Roy

Patrick Roy

May 3, 1986 — Prince of Wales Conference Finals, Game 2 (Canadiens vs. Rangers)

Patrick Roy

May 7, 1986 — Prince of Wales Conference Finals, Game 4 (Canadiens vs. Rangers)

Patrick Roy

May 7, 1986 — Prince of Wales Conference Finals, Game 4 (Canadiens vs. Rangers)

Patrick Roy

May 9, 1986 — Prince of Wales Conference Finals, Game 5 (Canadiens vs. Rangers)

Patrick Roy and Craig Ludwig

May 9, 1986 — Prince of Wales Conference Finals, Game 5 (Canadiens vs. Rangers)

Patrick Roy and coach Jean Perron

May 24, 1986 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 5 (Canadiens vs. Flames)

Patrick Roy

April 27, 1990 — Adams Division Final, Game 5 (Canadiens vs. Bruins)

Patrick Roy and Zarley Zalapski

May 1, 1992 — Adams Division Semifinals, Game 7 (Canadiens vs. Whalers)

Patrick Roy

May 9, 1992 — Adams Division Final, Game 4 (Canadiens vs. Bruins)

Joe Sakic and Patrick Roy

April 20, 1993 — Adams Division Semifinals, Game 2 (Canadiens vs. Nordiques)

Patrick Roy

June 1, 1993 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 1 (Canadiens vs. Kings)

Patrick Roy

June 3, 1993 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 2 (Canadiens vs. Kings)

Patrick Roy

June 7, 1993 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 4 (Canadiens vs. Kings)

Patrick Roy

June 9, 1993 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 5 (Canadiens vs. Kings)

Patrick Roy, wife Michele, sons Jonathan and Frederick, and daughter Jana

June 11, 1993 — Roy's home in Montreal

Patrick Roy

Dec. 7, 1995 — Colorado Avalanche locker room

Patrick Roy

May 25, 1996 — Western Conference Final, Game 4 (Avalanche vs. Red Wings)

Patrick Roy and Scott Mellanby

June 4, 1996 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 1 (Avalanche vs. Panthers)

Patrick Roy, Rob Niedermayer and Scott Mellanby

June 8, 1996 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 3 (Avalanche vs. Panthers)

Patrick Roy

June 10, 1996 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 4 (Avalanche vs. Panthers)

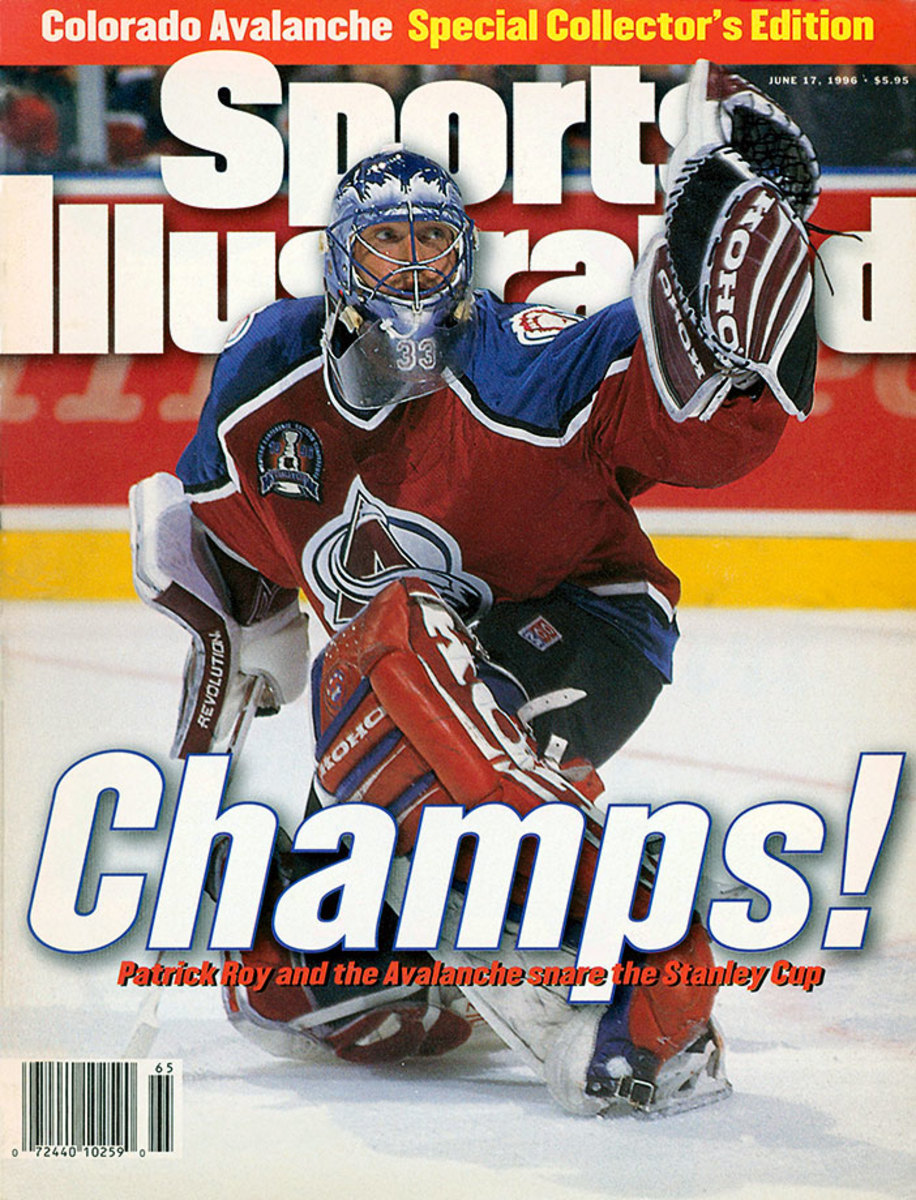

Patrick Roy

June 17, 1996 SI cover

Patrick Roy and Viacheslav Fetisov

May 26, 1997 — Western Conference Final, Game 6 (Avalanche vs. Red Wings)

Patrick Roy and Chris Osgood

April 1, 1998 — Avalanche vs. Red Wings

Patrick Roy

May 16, 1999 — Western Conference Semifinals, Game 5 (Avalanche vs. Red Wings)

Patrick Roy

April 2, 2001

Patrick Roy

June 2, 2001 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 4 (Avalanche vs. Devils)

Patrick Roy and the Colorado Avalnche

June 9, 2001 — Stanley Cup Final, Game 4 (Avalanche vs. Devils)

Patrick Roy and Steve Konowalchuk

March 19, 2002 — Avalanche vs. Capitals

Patrick Roy

March 12, 2002 — Avalanche vs. Red Wings

Patrick Roy, Tomas Holmstrom and Darius Kasparaitis

May 22, 2002 — Western Conference Final, Game 3 (Avalanche vs. Red Wings)

Patrick Roy

March 15, 2003 — Avalanche vs. Red Wings

Patrick Roy

Nov. 8, 2003 — Quebec Ramarts practice

Patrick Roy

Nov. 8, 2013 — Avalanche vs. Flames

Roy, though, had to learn with Roy. The next year, his game fell off, big time. He was the second best goalie on the team, behind 26-year-old Brian Hayward, who started 13 of the team’s playoff games to Roy’s six, which must have seemed like a Lovecraftian reversal of fortune at the time.

Hayward and Roy were basically the same guy in 1986-87, and Habs fans probably thought, O.K., the man had his moment, thanks for the Cup, now who will bring us the next one?

What analytics can tell us about the role of fighting in hockey

Come the next year, though, Roy was Roy, all the time, and would remain so into the next century. The butterfly style, that defiant, knee-based elegance, had been mastered. It was further outfitted with an all-timer of a glove hand, and a spirit of competitiveness—this attitude of "go on, punk, I dare you to try and beat me the the way I insist on playing" that Gretzky, Michael Jordan, David Ortiz, and very few others have possessed.

The high-flying age eventually petered out into the age of systems, puck possession strategies, cycling, double deflections, and “greasy goals,” all in an attempt to beat a goalie who could beat you by going to his knees. Which means any shot on goal in today’s NHL is a shot being fired at the legacy, and influence, of Patrick Roy. More pleasing than Gretzky or Orr? No. More relevant to what you see every night? Yep. Again, modes of efficacy, not points of artistry.

GAA is GAA, wins are wins and will forever matter most, and heavy is the burden of the goalie who refuses to drop and play from his knees. Nonexistent is the career of one unless another traiblazer like Roy comes along to move the game in a new direction.