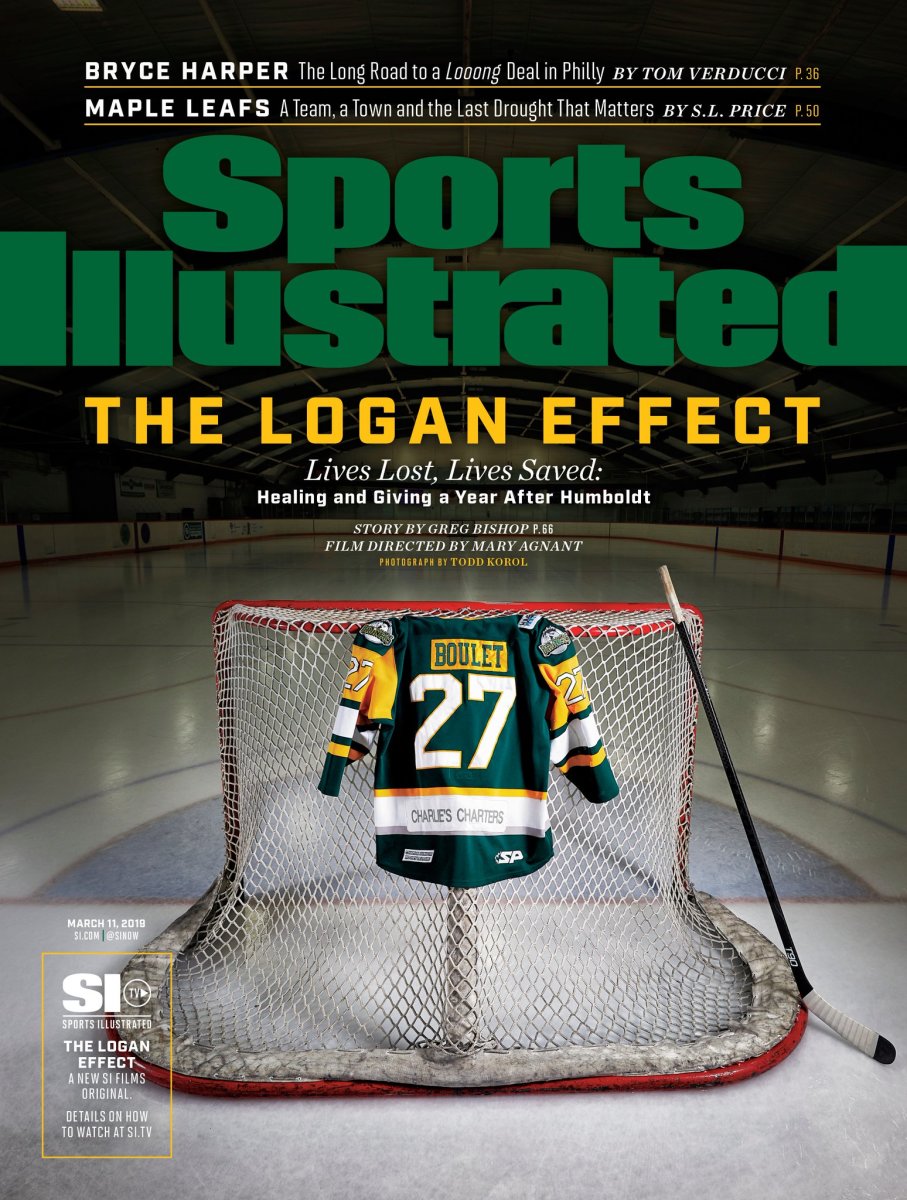

Life and Legacy

Special reporting by Mary Agnant. Watch The Logan Effect on SI TV. Our new SI Films original explores the aftermath of the tragic Humboldt Broncos bus crash through the story of Logan Boulet.

The beloved coach radiated crazy, everyone saw that. He promised to make the hockey hopefuls "farm boy strong" through the most unusual of methods. He forced the boys to sprint down BMX ramps, honed their Olympic weightlifting techniques, put them through Navy SEAL training exercises in the mud, hit Wiffle balls at them and had them drag dummies underwater across swimming pools. He made them brush their teeth and shade in coloring books with their nondominant hands, while concocting extensive calisthenics routines involving jump ropes, hand claps and skipping.

Sometimes Jenn Suggitt found that crazy coach, her husband, Ric, chuckling to himself as he searched the Internet before sunrise. When she asked why, he'd say, "You should see what I'm going to do to the boys this week."

Logan Boulet was his ringleader, a 19-year-old defenseman who almost washed out of junior hockey but best matched his torturer's manic temperament, who actually embraced crawling under barbed wire and dodging line drives. Suggitt, a nationally renowned rugby coach, had trained plenty of kids. When he landed at the University of Lethbridge in 2015 to coach the women's rugby team, he offered to train the team manager's boy and his friends under one condition: no dickheads. That was Suggitt: straightforward, gregarious, overly caffeinated. To Boulet he was simply Sluggo.

Their training began in the summer of 2016 and transformed Boulet from a tradable piece to a mainstay on the Humboldt Broncos in the Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League. They swam and crawled and sprinted until June 27, 2017, when Suggitt felt sick and decided to skip work. He never took days off. While driving one of his two daughters to swim club, he grabbed his head and told her he felt the "worst pain I've ever had in my life." Somehow, he managed to park the car and say, "I'm so sorry, call your mom." Those were his last words. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage at 58.

Boulet served as a pallbearer at his trainer's funeral, where he learned about a random conversation the Suggitts had three weeks before Ric died. Jenn had asked Ric if he was an organ donor. He checked his license, realized he wasn't and told her that he wanted to be. After the hemorrhage, Suggitt's brain ceased function but his heart never stopped beating, and because of that conversation, his wife insisted his organs be donated. (Under Canadian law, families can make organ decisions after death.) Doctors marveled at the strength of Sluggo's heartbeat; they'd never heard a donor's heart pump so hard.

That August, Logan sat in the hot tub on the deck in his backyard. He loved to soak there, maybe crack open a beer and admire the canyon and river that spread for miles down below. In passing conversation, he told his father, Toby, about the Suggitts' discussion and Ric's decision to become a donor. Logan explained how on his next birthday, his 21st, he planned to sign his donor card to honor Sluggo. Good for you, his father thought. "They're not going to want your organs when you're 80 years old," Toby responded. "But go ahead."

Logan turned 21 on March 2, 2018. He celebrated in Humboldt with his parents, his sister and his girlfriend, who had made the eight-hour drive for the occasion, and the Paulsens, his host family for three years. They fashioned a tiered birthday cake out of beer bottles with "2" and "1" candles on the top. Earlier that week, Logan had driven the Paulsens' 14-year-old son, McLaren, on an errand and upon returning, parked his red Volkswagen Jetta under the maple tree in the front yard.

"I signed my organ donor card," Logan said.

"Isn't that weird, getting your organs taken out?" McLaren asked.

"If I can help save six people, I'm gonna do it," Logan responded. Just like Sluggo.

Four weeks after that seemingly benign conversation, a truck struck the bus carrying the Humboldt Broncos to a playoff game in Nipawin, Saskatchewan. Sixteen passengers died, Logan Boulet among them. But his heart, like Sluggo's, never stopped pumping. Doctors, again, marveled at the strength of his heartbeat. And his organs, like Sluggo's, went to several recipients; he might have saved six lives.

All these individual events, when viewed separately, can seem arbitrary. Taken together, they look like something fateful, like something more. Logan Boulet died in a crash that made international headlines, that resonated with anyone who's ever gotten on a bus or, more poignantly, put their kid on one, in a country with a real organ-donation crisis due to abysmally low donation rates. His death started a national conversation and countless smaller ones, like the talk Jenn Suggitt had with Ric. In the months that followed, tens of thousands across Canada signed up to become donors.

The phenomenon became known as The Logan Boulet Effect.

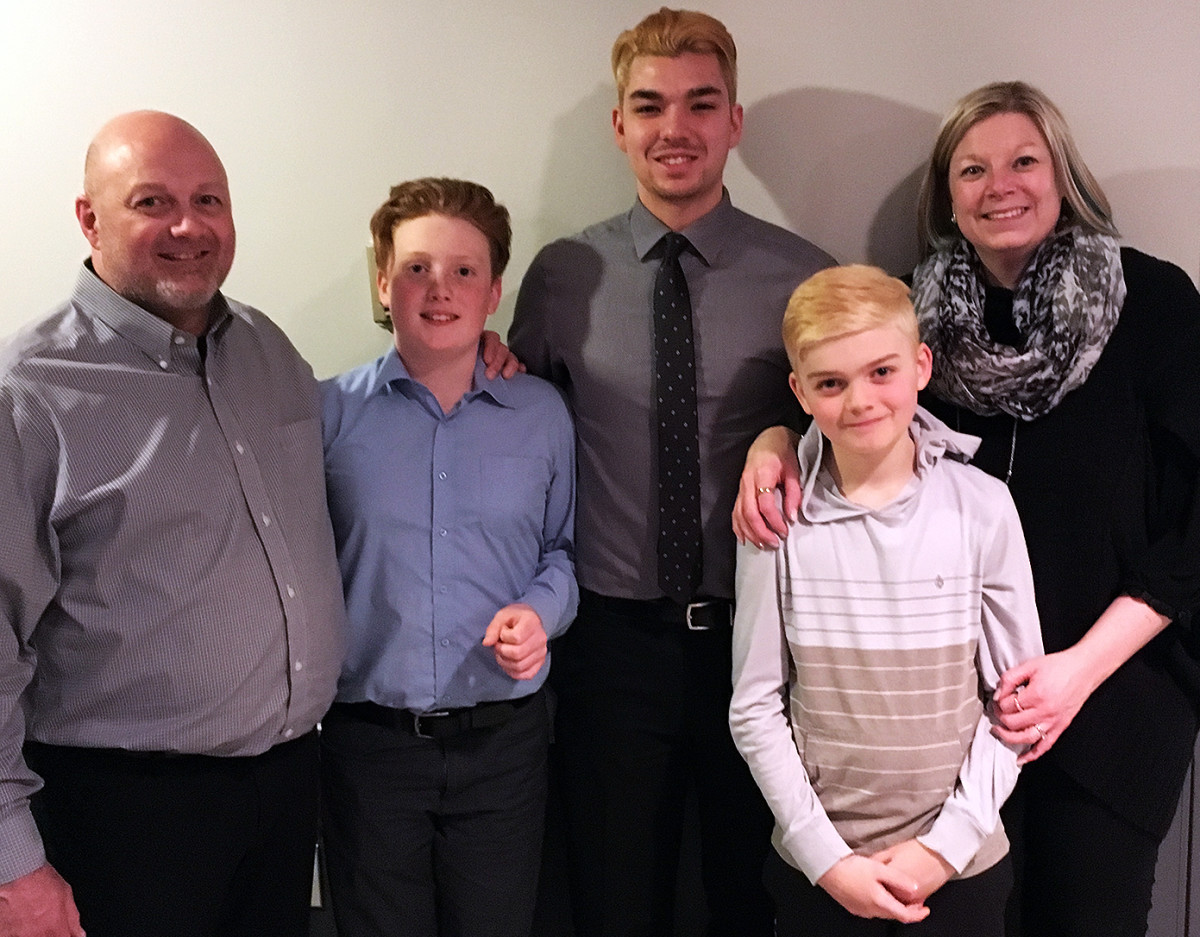

This crystallized both Logan's legacy and the dichotomy the Boulet family—Toby and his wife, Bernadine, and their 24-year-old daughter, Mariko—must now forever confront. Logan, his trainer and the choices the two made led to a movement, one whose impact was far greater than anyone could ever have expected—but that impact only became possible in death. There's unspeakable pain there. Comfort, too.

The Boulets still recall the birth of their second child in great detail. The heavy snowfall. The homemade beer Toby was bottling with his buddies. (They named that batch Logan Lager.) The rushed trip to the hospital. Bernie's quick labor. And their first and only boy, so tiny and so perfect. They named him after the tallest mountain in Canada, Mount Logan.

The son of two teachers, Logan lived an idyllic childhood. He hardly fought with his sister. Never, she says. He was happy and helpful and gloriously loud. He loved sports and played five growing up, including curling and rugby. He treasured sleeping in, traveled the world, collected Fanta soda cans and hockey cards and Lego sets, loved watching Disney movies and designing things like shoe racks to feed his artistic bent. A child with endless ambitions (archaeologist, policeman, engineer, architect), Logan dived into so many hobbies that his parents told him he needed to give something up. "I'll give up school," he told the two educators who stared back at him.

Logan did possess an angry streak that he struggled to control. He considered himself a protector and finished more scraps than he started. Around age 14, after one hockey team cut him, he found the perfect way to channel his aggression. He decided to devote himself to the sport—working harder, practicing longer, seeking a private skating coach.

Funneling that intensity onto the ice, he masked what he might've lacked in athletic gifts with a work ethic that walked right up to the border of unhealthy. He never got cut again. He spent his weekends criss-crossing through Western Canada—10 hours to Grande Prairie, six hours to Medicine Hat—always traveling the same way. "On the bus," Toby says. "For those hours, that's their home. That's where they exist."

To the delight of Toby and Bernie, Logan wanted to become a teacher when his playing days ended. And during the 2015–16 season, it looked as if maybe that time was fast approaching. Logan had signed with the Kindersley Klippers of the SJHL, but they traded him to Nipawin after 12 games. Soon he was on the block again, told by management that his career might be done. At that point Logan concocted a plan with his uncle, Kevin Higo, a longtime hockey coach: They'd find a trade partner or he'd quit.

Higo called an old friend, the rookie coach in Humboldt, Darcy Haugan. He knew Haugan had set out to change the culture of a franchise that had won two national titles but fallen into decline. He wanted to restock his roster with tough, coachable, driven players. Haugan traded for Logan in late November 2015 and introduced him to hockey life in Humboldt: the game-day volunteers who staffed Elgar Petersen Arena, the locals who donated farmland to raise money, the rabid fans who removed their shirts when "Cotton Eye Joe" played.

Logan settled into the Paulsens' basement. Gavin and Natasha Paulsen had been housing players for years, despite their initial hesitation over the cost. The players who moved in became like family, befriending McLaren and his younger brother, A.J., helping with chores, driving the boys to hockey practices.

After only a few days, Logan called home, his voice tinged with excitement. He had aided Gavin in constructing a rink in the backyard. So cool, he kept repeating. He helped McLaren and 11-year-old A.J. hone their hockey skills on the rink, showing them how to bodycheck and working on their shooting form. The brothers nicknamed him Young Savage, and chanted it whenever he came home. When McLaren was cut from a local team, Logan comforted him, sharing his own experiences. They put together a Sluggo-esque plan. McLaren promised to phone the next year when he found out if he made the team.

By the start of his third season in Humboldt, his last year of junior eligibility, Logan had earned the alternate captain's A. The gritty, grind-it-out defenseman who killed penalties and blocked shots also had a career-high eight goals and seven assists through the first 37 games of the 2017–18 season. And he mentored younger players, collected team fines and helped Haugan achieve the culture he desired.

Logan did miss 16 games after he broke an opponent's nose and his own right hand in a fight on Dec. 9. He spent Christmas in a cast at home in Lethbridge.

"You need to leave a legacy," his uncle Higo told him. "You need to be the guy who in five years, when you're gone and they're looking at pictures, they say, I remember Logan Boulet, because he did that." Logan returned at the beginning of February, just in time for the playoff push, determined to leave the imprint his uncle had envisioned.

Jason Neville, the Broncos' assistant general manager, says that next stretch marked the best hockey Logan ever played. The Broncos went 7-4-1 to finish the season and made the playoffs, toppling the higher-seeded Melfort Mustangs in the first round. The players sat for a team photo after they clinched the series, the frame filled with so many golden-haired boys, their mops bleached blond per postseason custom.

Humboldt dropped the first two games of their semifinal round series against rival Nipawin. But the Broncos took Game 3 when Boulet scored the winner, and the home fans went berserk. The victory ended a streak of six straight postseason losses to the Hawks and bolstered Boulet's confidence. Dan Ukrainetz, Nipawin's color commentator, told Toby after the game that Logan was the best player on the ice. Logan scored again two nights later, but the Broncos fell in triple overtime, a game that ended just before midnight on April 4.

The next day, with Game 5 looming, the Boulets hung out with Logan and ate dinner with him at Johnny's Bistro, his favorite Humboldt restaurant. They watched TV together at their hotel and picked out color swatches for Mariko, who was thinking of repainting her room at college. As he left, Logan hugged his mom and shook his father's hand; he told them he'd see them the next night in Nipawin, after Humboldt won.

It gnaws at Bernie that she didn't snap a picture with Logan that night, her greatest lingering regret.

Late on the afternoon of April 6, Kelsey Fiddler pulled her red Buick Century up to the rural Saskatchewan intersection known as Armley Corner, about 45 minutes from Nipawin. Paused at a stop sign, she didn't notice the six white, wooden crosses staked into the ground nearby to remember the family killed in a 1997 collision there.

Heading east on Highway 335, Fiddler was waiting for the Broncos' bus, which was heading north on Highway 35 and had the right of way, to pass. A tractor-trailer filled with packages of peat moss sped west on 335. Fiddler saw everything "in slow motion." She remembers that it was cold, she was 28 weeks pregnant, and her two boys were buckled into the backseat. Debris from the impact collided with her windshield and flew over her car. Hockey sticks lay everywhere. She dialed 911 and told her children not to look at the crash, even as they could not turn away.

Fifteen minutes later, as he approached Armley Corner, Toby Boulet saw police lights flashing ahead and then a Humboldt Broncos hockey bag lying in a ditch on the side of the road. His stomach dropped as he saw the overturned semi, then the bus. He stopped his car and ran to the wreckage, ignoring the officers who told him to turn back. Toby later told one confidant that the inside of the bus, with its strewn metal, looked like a jungle gym, except with the lifeless bodies of so many hockey players scattered about, some even hanging upside down. He heard screams from people trapped underneath the bus and pointed at one, yelling that the person's feet were moving.

Toby searched frantically for his son. Some of the faces he had known so well had been mangled beyond recognition. That all the boys had dyed their hair only made it harder to tell them apart. Eventually another dad told Toby he had found Logan. Toby went to a gurney, lifted a blanket and saw a young man, severely injured and covered in blood. To this day he does not know if it was his son or not.

McLaren, whom the Boulets were driving to the game, stayed in the car with Bernie. He held her hand, telling her that everything would be O.K. "I lied," he would later tell his parents.

They drove to the hospital in Nipawin, where doctors told them Logan, alive but seriously injured, had been helicoptered to Saskatoon. As the Boulets drove there, desperate but trying to remain hopeful, they considered the best-case prognosis: that he might live in a permanently vegetative state.

After a harrowing three hours on the road, the extent of Logan's injuries became heartbreakingly clear. Joann Kawchuk, the critical-care physician in charge of the ICU that night, filled the family in. Other than a small scratch on his head, a lump on his temple, a cut on one big toe and some bruising Logan looked remarkably normal after he had been cleaned up. His scans, however, told a more devastating story—a broken neck, a broken spine and a massive brain bleed at the base of his skull. Kawchuk described the damage as irreparable. Logan, she said, would not recover.

The ICU was operating under Code Orange, meaning mass casualties. The first patients arriving all required life support. The unit, Toby says, resembled the TV show M*A*S*H—"just trauma, everywhere." Mariko calls it "the worst thing I've ever seen."

The doctor can still vividly recall Logan's parents: Toby, the tall man with the strong hug who used disinfectant wipes to clean the blood from his son's face; Bernie, the composed mother with the warm, generous eyes. After digesting the prognosis, she asked, "Can we donate his organs?"

His family spent the next 27 hours with Logan. They note now how the time matched his jersey number and the day (June 27) that Suggitt died. None of it seemed random, except of course the crash itself. Logan's uncle downed one last beer at his side. His sister told tales of their travels. His parents read his favorite children's books (Koala Lou and Go, Dog. Go!). His mom spent hours just listening to his heartbeat, her head resting upon his chest. Doctors, nurses, everyone told them the same thing—for an organ donor, they'd never heard a stronger heartbeat. Just like Sluggo.

Near the end of those 27 hours, a nurse brought in several hospital bracelets. She encouraged everyone to write messages to Logan and secure the bracelets on his arms. Mariko scribbled something like, "Thanks for the adventures; I'll always be proud to be your sister." Bernie prefers not to share what she wrote, but she placed that band on his body last, on the upper part of his left arm, closest to his heart.

When their final hours together ended and it was time to take him off the respirator, doctors wheeled Logan into surgery. The hardest part, says Mariko: "We walked down the hallway. My mom held Logan's hand, and my dad and I held hands behind. I was just staring at Logan. These people stopped, and it was all Humboldt families, and they watched us walk by. Knowing that would be the last time I saw him ... hearing him breathing ... seeing his heartbeat."

As the Boulets left the operating room, coolers were brought in to transport Logan's organs. Of all the victims, he was the only donor. Toby wanted to touch each individual container, but instead he looked back and saw his boy, his arms and legs lined with all those bracelets. "He looked beautiful," Toby says.

Much of the information about the crash the Boulet family read in the immediate aftermath was exaggerated, misleading or flat-out wrong. They asked Neil Langevin, a family friend and Logan's godfather, to write a Facebook post that would explain exactly what had transpired. Logan donated his heart, lungs, liver, kidney, pancreas and corneas. Officials would later tell the family that all six transplants were successful, that all the recipients were still alive.

Langevin composed that post on April 7, writing about Logan and his decision to donate and his "selfless and benevolent nature." Within a few hours, the update went viral. Fiddler, the crash witness, saw it; so did Michael Grant, one of Sluggo's other disciples; and everyone else Logan knew. Hundreds commented. Thousands more shared, from as far away as Australia.

"That's where The Logan Boulet Effect started," Toby says. He sometimes refers to the movement as their "silver medal," the best thing to come out of their worst loss. If they couldn't have Logan, at least they could have this, the knowledge of lives saved. Someone mentioned to Mariko how "cool" it was that Logan had decided to donate his organs. "No," she responded. "He had to die for that to happen." But still it meant something—and would grow to mean more to her as time went on.

In the first weeks after the crash, the Boulets tried not to go anywhere. Every random encounter at the grocery store led to a conversation about Logan. "The size of the tragedy, the scope, his decision, it just magnifies the grief," Toby says. "They just stand there and look at you. I'm like, either hug me or move on."

The Boulets held a Celebration of Life for Logan back in Lethbridge. Firefighters played "Scotland the Brave" on bagpipes. Seats filled up hours before the service started, with hundreds spilling over into the aisles. Grant skipped a playoff practice for Nipawin to serve as a pallbearer, just as he and Logan had done for Suggitt. His team wore green helmets the rest of the season in honor of the Broncos. Logan's science teacher spoke about choices, like the ones Logan made before his death, unaware of the effect they would create. That made him a true hero, the teacher said.

Back in Humboldt, the Boulets cleaned out Logan's locker. He had taped two pictures at the top. One featured his family. The other: Sluggo.

Logan had scribbled WORK HARD in between them.

On a brisk September morning last fall, Toby Boulet pulls into the parking lot outside his classroom at Winston Churchill High. As on all days, he is constantly reminded of Logan, from the snapshots hung up in his shop classroom to the pictures displayed in the halls to the 27 on his green shirt. Today his inbox has an email from an MP who hopes the Boulets would support a bill that will make it easier for Canadians to become organ donors by adding a simple yes/no line to annual tax forms.

His students measure, saw and drill for the next 90 minutes, as Toby, or Tobes as they call him, monitors their progress. Sometimes he finds this time distracting, a welcome break from the hopelessness that threatens to overwhelm him. Other times he looks at these students—in these hallways, some hockey players, discussing their travels, their hobbies, their favorite movies—and sees in them his son. Sometimes he can feel his boy's presence, right there in the room. The same word rings in his head. "Logan, Logan, Logan," he says.

As on all days, Toby returns to the house with the hot tub on the porch out back. Green-and-gold ribbons adorn the trees in front. A wreath, made of 16 roses, hangs on the door. The untouched downstairs bedroom, where the Boulets always leave the light on, is still packed with Fanta cans and Lego sets. Upstairs, a room is filled with handmade quilts and green bracelets and books on how to grieve. And the cards, thousands of cards, sent from all over the world. "Sometimes it's like we're sharing our kid with everybody," Bernie says. "But that's not a bad thing."

Moving forward remains complicated. Moving on, impossible. Toby helped Neil Langevin coach the women's rugby team at the University of Lethbridge last fall—the same team that Suggitt returned for—and that meant riding buses to away games.

Neville, the Broncos' assistant general manager, rebuilt an almost entirely new team. He spent three months watching tape and calling players, laying out the situation in Humboldt, convincing them to play for a grieving city with the world watching. Many turned him down, not wanting to deal with the extra pressure. But 23 players eventually signed on, each unaware of Neville's own unprocessed grief. He was supposed to have been on that bus but stayed home because his parents were in town. "There's a lot of guilt," he says. In September, he resigned.

The Paulsens chose to billet again, but after both players they housed this past season were traded, they decided not to take in another. McLaren made the team that Logan helped him train for, wore number 27 and recorded 17 points in his first 27 games. He never got to make that phone call, but sometimes he can hear Logan's voice in his head, shouting, "Skate faster!" He plans to put a YOUNG SAVAGE license plate on his first car.

The GoFundMe page that collected donations for the victims and their families in the wake of the crash became the largest in the history of Canada, with more than 140,000 donors from at least 80 countries contributing $15.1 million. Each survivor will receive $475,000. Each family that lost someone will get $525,000.

Logan's friends and relatives inked his name, his initials or hockey sticks on their bodies. Fiddler, the crash witness, named her baby girl Logan Humble Strong. Sometimes she sends Bernie baby pictures. Sometimes she dreams about those hockey players. "They're my guardian angels," she says.

The Boulets returned to Humboldt for the Broncos opener in September. From their hotel, they watched two planes fly overhead, emitting smoke to create two halves of one heart. At the game they saw thousands of faces stained with tears in the stands. A moment of silence, a ceremonial puck drop, a national television audience and 29 banners that would later be raised, one for each of the passengers on the bus. "It broke me," Toby says.

The Broncos ended up contending, despite everything. The Boulets followed as the season progressed, as Humboldt carried a 10-game winning streak deep into February and climbed into first place. The Broncos continued to travel to every away game, even to the ones in Nipawin, the same way—by bus.

In late January the Boulets attended a hearing for the truck driver. They presented to the courtroom the first of 75 victim impact statements. The driver, Jaskirat Sidhu, had already pleaded guilty to 16 counts of dangerous driving causing death and 13 more counts of dangerous driving causing bodily harm. The Boulets were relieved that there wouldn't be a trial, but they wanted Sidhu to know how many lives he had irrevocably changed, how many families he had broken. It was hard for the Boulets to listen to the other families, those who had go to morgues to identify their children, who didn't get 27 hours to say goodbye.

"More often than not I forget. I forget that Logan's gone. I forget how permanent this is. I forget that the only place I can see and talk to him is in my dreams.... I am an only child now," Mariko wrote.

The Boulets seek comfort in the bigger picture, the best thing that came from the worst thing and the only thing that makes them feel even a little bit better as the anniversary of the crash approaches. They're not sure exactly how many donors signed up after Logan's death or how many of those donors signed up because of Logan's story. But the numbers they have heard—100,000; 200,000; even more—are staggering. Imagine when those new donors tell their friends, who tell their friends, and how many of those people will sign up. "Like ripples in a pond," says Jenn Suggitt, whose husband tossed the first stone.

The Boulets heard directly from thousands, through letters, email or social media, who said they joined the movement because of Logan. Families reached out to say they had lost loved ones who donated their organs in his memory. One woman told them that all four of her quadruplets pledged to become donors on their 19th birthday. Hoping to sustain that momentum, the Boulets are in the process of creating a foundation. On April 7, the anniversary of his death, they and thousands across Canada will take part in Green Shirt Day to raise awareness for organ donor registration.

Remember the legacy that Higo implored his nephew to cement? Right there. That's it—the conversations that will reverberate far longer and far wider than anything he might have done on the ice.

Sometimes Logan's sister and his girlfriend laugh about how much Logan himself would have hated all this attention, all the speeches, all the times his family told the story of his life and the overwhelming impact of his death. For a week last summer, Bernie noticed a moth flying nearby whenever the Boulet family sat outside, landing on the empty chair where Logan would have sat. She often finds dimes in her pockets, and in Canada, she says, that means someone who died is thinking about you. These small things bring small comfort, but she'd trade all of it, of course, for another embrace.

"I would love," she says, "to hear his heart beat again."

A short drive from the Boulet house, a cemetery rises from a hillside. Logan's grave sits near the far edge. It's decorated with orchids and hockey sticks and a rock with the word love carved into it. In an adjacent plot rests Ric Suggitt. Together, the graves speak to the randomness of human existence, how one man impacted one hockey player and how that hockey player impacted hundreds of thousands of other lives. All because of the choices made by two friends before two vehicles collided on a lonely stretch of highway in Nowhere, Saskatchewan. What are the chances?

The Boulets, awash in irreconcilable emotions, face their new reality with little hope they'll ever feel whole again. The best thing from the worst thing doesn't erase the worst thing; it just makes the worst thing mean something. Now they attempt to amplify the good that has come from the tragedy they share, like their son, with the world. There's unspeakable pain there. Comfort, too.

Become an organ donor: For more information and to register online, visit beadonor.ca in Canada or organdonor.gov in the U.S.

This story appears in the March 11, 2019, issue of Sports Illustrated. For more great storytelling and in-depth analysis, subscribe to the magazine—and get up to 94% off the cover price. Click here for more.