After rehabilitation, the best of Michael Phelps may lie ahead

An abridged version of this story appears in the Nov. 16, 2015, issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

For almost five days in the fall of 2014, the most decorated Olympian in history lay curled in a fetal position in his Baltimore home, crestfallen and fearful, embarrassed at his behavior and uncertain of his future. Over three Olympics, from 2004 through ’12, Michael Phelps had won 18 gold medals and 22 medals overall, each total more than anyone ever. His swimming had been transformed by NBC into a nightly television miniseries, and millions watched as Phelps splashed to victories for America over the rest of the world. His family watched at poolside, supporting players in an emotional drama that was the paradigm of Olympic success and Olympic packaging. His story had the perfect arc: In 2000 he was a prodigy; in ’04 he was brilliant but imperfect; in ’08 he was unbeatable; in ’12 he was a legend on his farewell tour, diminished but still great. Three times he emerged a celebrity—each time a little more famous, a little more wealthy and a little more entrenched in the mythology of his quadrennial feats.

His life had been turned into a flat-screen American athletic dream: A skinny boy with big feet (and ears) had been transformed by endless laps and a wise coach into a red-white-and-blue, gold-medal-winning machine. Imagine our relief when he announced last spring that he would swim in one more Olympics next summer in Rio de Janeiro, his fifth (and surely his last?). Yet this was just half the story. Phelps was also an adult approaching 30, whose reality was approximating the two-dimensional cardboard cutout on all those television screens. That skinny boy had failed to find the same traction on land that came so naturally in the water. He had never come to terms with the father who was divorced from his caring and supportive mother when Phelps was nine. He had found a woman to love and lost her. He had welcomed far too many sudden friends and had embraced the perks of affluence and celebrity more than was healthy. “I look back now,” says Phelps. “I lived in a bubble for a long time.”

Now that bubble was a prison of sorts. On the night of Monday, Sept. 29, 2014, Phelps drove from his home to the Horseshoe Casino near Baltimore’s harbor. At 1:40 a.m. he was stopped by an officer with the Maryland Transportation Authority while exiting the Fort McHenry Tunnel. Police had clocked Phelps’s white 2014 Range Rover at 84 mph in a 45-mph zone, and observed Phelps driving erratically. According to a police report obtained by The Baltimore Sun, Phelps failed two field-sobriety tests and a Breathalyzer put his blood-alcohol level at .14, above the state driving limit of .08. He was charged with DUI, excessive speed and crossing double lane lines. (Last December he pleaded guilty to a drunk driving charge.) A decade earlier, at age 19, shortly after the Athens Olympics, Phelps had pleaded guilty to driving while impaired; in ’09 he had been entangled in controversy (and suspended for three months by USA Swimming) after a British tabloid published a photo of him smoking a bong. This arrest was much bigger, not just because it was the third incident in a decade, but because the speed and level of intoxication made it more dangerous and hinted at larger problems.

Phelps’s mother, Debbie, who directs the Education Foundation of Baltimore County Public Schools, got the news at work in a call from Phelps’s agent, Peter Carlisle. “I just put my head on the desk,” says Debbie. “I thought, Oh, my God, here we go again. How terrible is the world going to be to my son?”

His father, Fred, who spent 28 years as a Maryland State Trooper before retiring from that position in 2003, works in commercial vehicle enforcement training. He got a call from a friend at the transportation authority who had seen the night’s arrest log. Cops take care of cops. “I asked if Michael was O.K.,” says Fred. “He said he was O.K. and then gave me the details, and I just thought, Oh, jeez.”

Brian Shea, a pharmaceutical sales representative and one of Michael’s best friends, was driving to a sales call when he got a text from his wife. “I pulled over and read the message, and I called my wife and said, ‘You’re kidding, right?’ ” says Shea. “I just slinked down in my seat right there next to the road. I felt so disappointed.”

Carlisle also phoned Bob Bowman, Phelps’s longtime coach. “I had been living in fear that I was going to get a call that something had happened,” says Bowman. “Honestly, I thought, the way he was going, he was going to kill himself. Not take his own life, but something like the DUI, but worse.”

Phelps apologized in a public statement. Friends and family gathered at Michael’s house: Debbie; sisters Hilary Phelps, 37, and Whitney Flickinger, 35; Carlisle; Shea; and several other longtime Baltimore friends, including former Ravens linebacker Ray Lewis, who had become friendly with Phelps several years earlier. (“He’s like a brother to me,” says Phelps.) Phelps’s girlfriend (now fiancée), Nicole Johnson, texted and called from California. Bowman was not there, but he also talked to Phelps on the phone. “He wouldn’t see me,” says Bowman. “He’s embarrassed when something like this happens.” Fred Phelps was not there; he and Michael were not close at the time. Those who were in the house found a distraught Phelps, shaken at his poor judgment, terrified of its consequences. “It was bad,” says Shea. “It was every bit as bad as you would imagine. You could see he was feeling the weight of his actions. He knows he has kids who look up to him. He has his foundation. He knew he let people down, and he had no idea exactly what was going to happen.”

News organizations were camped nearby, looking for a glimpse of Phelps, who did not leave the town house for four days. “I was in a really dark place,” Phelps says. “Not wanting to be alive anymore.”

Phelps’s support team began to discuss the possibility of him checking into a treatment facility. To this day, no one close to Phelps will say that he has a drinking problem, although none dismiss the perils of drinking and driving. “He has a unique and challenging life, and he was clearly struggling,” says Carlisle. “This was an opportunity for him to finally learn some of the tools he needed to deal with that life.” The idea gathered support, though Phelps was unsure. Lewis was among those who pushed. “I gave him some harsh reality,” says Lewis. “I said, ‘Bro, what are you doing with your life?’ ’’ (Phelps says, “He tore me a new one.”) Bowman also pushed, in a phone conversation. “When I talked to him, he said, ‘I don’t think I can do this.’ I said to him, ‘You can do it, and you have to do it.’ ”

Gradually the vote became nearly unanimous, and Phelps began to embrace the idea. On the weekend following his arrest, Phelps flew on a chartered private jet from Baltimore to Wickenburg, Ariz., with Hilary and Johnson. They were picked up and taken to The Meadows, a residential treatment facility in the desert. “My brother was like a scared little boy on that trip,” says Hilary. Once there, the then 29-year-old hero of three Olympic Games was left alone, stripped of the personality that had publicly defined him. “Hug-hug, kiss-kiss, turn in my phone and go to my room,” says Phelps, “It’s probably the most afraid I’ve ever felt in my life.”

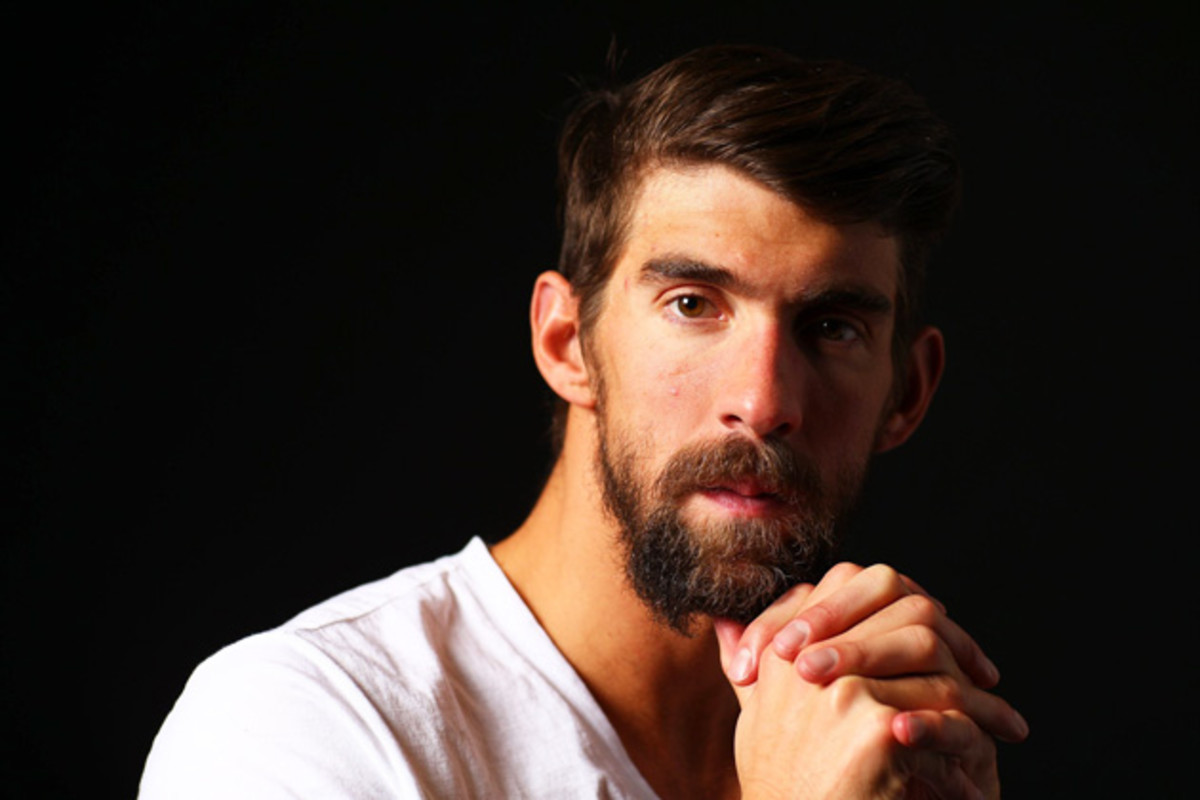

It is mid-morning in October at Arizona State University, and the autumn sun has already pushed the temperature into the low 90s, en route to 104°. Bowman stands in precious poolside shade, wearing a yellow Sun Devils T-shirt emblazoned with maroon pitchfork logos. He was named the school’s head coach of men’s and women’s swimming last April, and also brought—or was followed by—a postcollegiate training group of 13 swimmers. The most significant of these is Phelps, who climbs out of the water after a light swim. A more rigorous session will follow in the evening. He is bearded and deeply tanned, his skin pocked with baseball-sized welts left behind by cupping therapy, a suction-based practice that approximates rapid deep-tissue massage. It’s foolish to assess an athlete’s appearance; slow swimmers can look sensational on the blocks. But the rumors appear to be true: Phelps has a different profile—leaner and more muscular than in past Olympic years.

Phelps returned to training last fall after 45 days at The Meadows, and almost immediately the swimming world buzzed with talk of his workouts and renewed commitment. He trained hard and swam unevenly at several meets, and then in August, while most top U.S. swimmers raced in the world championships in Kazan, Russia, from which Phelps was barred under the terms of his suspension, he lit up the national championships in San Antonio. Phelps first won the 200-meter butterfly in 1:52.94, his fastest time since setting the world record in 2009. One night later, after South African Chad le Clos had won the 100-meter butterfly at worlds in 50.56 and dogged Phelps in a postrace interview—“I just did a time [Phelps] hasn’t done in four years. So he can be quiet now”—Phelps took the event in 50.45, also his fastest time in six years. Both butterfly times were Phelps’s fastest without wearing one of the high-tech, full-body racing suits that dominate the world-record lists and were banned in ’10. On the third night of the championships Phelps won the 200 individual medley in 1:54.75, his fastest time in four years. All three of Phelps’s swims were the fastest in the world in ’15, and all three would have won the world championship.

News of his performances rippled through the swimming community. Phelps has always been gifted: He made the 2000 Olympic team as a 15-year-old and at that same age became the youngest swimmer to set a world record. But his training had not always been consistent or disciplined. Days after leaving rehab, he told Carlisle, “Peter, it’s going to be interesting. I’ve never really given it everything I have.”

Lenny Krayzelburg, who won a total of four medals at the 2000 and 2004 Olympics and roomed with the then-19-year-old Phelps at the ’04 Games in Athens, says, “Sometimes you look back on your career and say, ‘Did I ever swim my best race? Did I ever really maximize myself?’ I saw Michael last summer in Los Angeles and he looked like he was in fantastic shape.’’

Bowman says Phelps did not miss a practice leading to the nationals this year, a streak that remains intact. Phelps publicly vowed not to drink alcohol at least until the Olympic Games are finished next August. After years of regularly gutting out workouts while hungover, Phelps is training clean. “Haven’t had a single sip and will not have a sip,” he says. “My body fat has dropped significantly, and I’m leaner than I’ve ever been. The performances were there because I worked, recovered, slept and took care of myself more than I ever had.”

Longtime coach Eddie Reese, who has been the head coach at Texas for 38 years and a head or assistant coach on seven Olympic teams, saw Phelps at the U.S. nationals. “You take the pluses of not drinking anymore and add his strength and physical maturation,” says Reese. “I think we’re going to see him go faster than he’s ever gone. Faster than [high-tech] suit times. He’s going to be very, very hard to beat.” Bowman, who has been watching Phelps’s workouts for two decades, concurs. “If we can continue like this until August, he will swim at this top level,” says Bowman. “He will swim his best times, and I think he will approach his [tech] suit times.”

This is all stunning. Phelps is likely to swim the same three individual events that he swam in San Antonio, although some in the swim community think he will add a freestyle event. (Says Bowman, despite Phelps’s improved condition, “I don’t think his fitness level would cause us to add another event.” Which is not the same as saying no.) Sixteen years after his first Olympic appearance, Phelps will be a gold medal favorite in three individual events and, pending the state of U.S. relay teams (they struggled at the world championships), he could contend for three others, a span of excellence that is wildly unprecedented. “My sport is a numbers sport,” says Phelps, the nerdiest of swim nerds, a walking database. “I have goals that I want to hit.” He would become the oldest swimmer to win an individual gold medal (the current record holder is the legendary Duke Kahanamoku, who won a gold medal at age 30 in 1920) and the first to win individual gold medals 12 years apart. (Phelps is one of three swimmers to win gold medals eight years apart.) His medal record, already unimaginable, will become surreal.

And: That’s the simplest part of this comeback story.

****

Phelps emerges from practice in a T-shirt, Orioles throwback cap and floppy workout shorts. We walk two blocks to a Tempe breakfast eatery where Phelps stops at least three times a week, usually after weightlifting sessions. Not long ago the chef mixed up a batch of Cap’n Crunch French toast for Phelps and labeled it Cap’n Phelps French Toast on the chalkboard of daily specials. It sold out. Now Phelps orders three chicken sausage tacos and a pineapple upside-down pancake, with coffee and ice water. It’s a hefty order, but decidedly less than the 4,000-calorie gut buster he used to eat—often with visiting journalists—at his favorite North Baltimore diner before the Beijing Olympics. (In 2004, Krayzelburg told Phelps his body would someday rebel against those massive meals.)

After spending his career in four-season climes—Baltimore and Ann Arbor, Mich.—Phelps has embraced Phoenix, where he lives with Johnson in a sprawling rented house in North Scottsdale, 30 minutes from the practice facility in Tempe. For the first time in his life, he will do most of his training—but for trips to Colorado Springs for altitude sessions—in an outdoor pool. “You have a different energy outside,” says Phelps. “You finish swimming and look up, and it’s a blue sky with no clouds. That’s pretty amazing to me.”

Like many U.S. journalists, I have passed in and out of Phelps’s career—the in occurring around the Olympics. We talked three times at length before the 2004 Games, for a cover story in Sports Illustrated. The first of those interviews was in the late autumn of 2003, in a cluttered room over the pool at the North Baltimore Aquatic Club. At the time, I was 47 and Phelps was a shy 18-year-old. My teenaged son suggested I engage Phelps by talking about Halo, a video game that had exploded into the market two years earlier. Phelps had brightened when I mentioned the game. “That game is so sick,” he said. It gave us a little common ground and an awkward interview some momentum. I related the anecdote to Phelps. He laughed. “I was playing a lot of Halo back then,” he says. It’s instructive now to see the young boy somewhere deep inside the man, 12 years, 22 medals and thousands of interviews later. Much of the awkwardness is gone, although this is a recent development, the product of struggling and falling and of the lessons learned in those 45 days at The Meadows. “He seems more peaceful,” says Hilary. “He was always a little irritated before, tense. He’s letting things go now. I think that’s what happens when you’re stripped down to such a raw, painful place.”

Phelps turns sideways at the breakfast counter. He has a story, and he would like to tell it.

His eight gold medals in 2008, breaking Mark Spitz’s revered 36-year-old record of seven golds, required Phelps to swim an astounding 17 races in nine days. Some were easy (his romp in the 400-meter IM) and some were not (the U.S. victory in the 4 × 100-meter freestyle relay, anchored by Jason Lezak’s miraculous swim). But that week had been built on a 13-year foundation of Bowman’s planning and Phelps’s training. It would prove impossible to sustain for another four years. Phelps won five gold medals and set two individual world records at the ’09 world championships in Rome, and two more individual golds (but also two silvers) at the ’11 worlds in Shanghai. He was doing it on the fumes of his pre-Beijing training. “To be honest,” says Bowman, “I was doing it with smoke and mirrors.”

Says Phelps, “After ’08, mentally, I was over. I didn’t want to do it anymore. But I also knew I couldn’t stop. So I forced myself to do something that I really didn’t want to do, which was continue swimming. That whole four-year period, I would miss at least two workouts a week. Why? Didn’t want to go. Didn’t feel like going. Screw it. I’m going to sleep in. I’m going to skip Friday and go for a long weekend.”

Shortly after Beijing, Bowman created what he called Friend Fridays, when Phelps’s nonswimming friends were invited to the pool, as an enticement to get Phelps to show up. Bowman would write workouts for everybody. Sometimes it worked and sometimes it didn’t. Shea says, “I told Michael, ‘If I show up and you’re not there, we’ve got a problem, because I am not a swimmer.’ ”

Phelps’s discipline rose and fell during the year before the London Games, until an episode just a few months before the opening ceremony, 10 days before an Olympic media event in Dallas in May. “Michael was actually starting to do O.K.,” says Bowman. “He had put together a couple good weeks of training, and I was thinking maybe this will be all right. We got back to Baltimore on a Monday, and we’re doing a typical [lactate] threshold set and Michael and [training partner] Chase [Kalisz] touch almost at the same time—bing, bing. I just yelled out the same time for both of them. Michael yells, ‘Are you going to time me or what?’ I gave him [a separate] time and then he started swimming slowly, which is what he does to piss me off. I yelled at him, ‘My timing has been good enough for the last 15 years.’ We go at it. World War III. I smash my watch against the wall. We get into the parking lot, and I peel out and flip him the bird, and he flips me the bird. Well, he doesn’t come back for 10 days. He finally shows up on Day 11 because Matt Lauer was in town to interview him for the Today show. They had no idea. That’s what our preparation was like for London.”

After that incident Bowman took Phelps to Colorado Springs for altitude training and stayed six weeks before the Olympic trials. “People thought it was a genius training plan,” says Bowman. “The truth was it was the only way I could keep him at practice.”

Phelps’s first London event was the 400-meter individual medley, the most grueling of his four individual swims and the event in which his lack of training was most likely to be exposed. He finished fourth, as countryman Ryan Lochte won gold. “My mistake,” says Bowman. “I got him to do the IM so I could get him enough training for the other events. It worked for the other events. I thought he would swim a s----- IM and finish second. He swam a s----- IM and finished fourth. I was an idiot.” U.S. writers stuck a fork in Phelps’s career. “Not often do you witness, with your own eyes, an entire era coming to such a definitive and complete end,” wrote Mark Purdy of the San Jose Mercury News. (In fairness, I wrote: “This Phelps looked a little like Joe Montana playing for the Chiefs or Michael Jordan for the Wizards,’’... but also, “It is early yet. Phelps could win several gold medals before London ends.’’ Guessing.)

Phelps won four gold medals before the Games were finished, but the race that he and Bowman remember best is the 200 butterfly, in which he lost by .05 of a second on the wall to Le Clos. “That was a freaking miracle by a guy who didn’t train for that event for three years,” says Bowman. “No one else in history could reach down like that, at that moment, and get to the point where he could get outtouched by five hundredths.” Or as Lochte puts it, “Michael is the best racer in the sport. People say he did all this work or didn’t do all this work. When he gets on the blocks, he’s going to race.”

Janet Evans, a respected swim legend who won four gold medals in 1988 and ’92, says, “The guy is good when he doesn’t train. He’s great when he does.’’

After London, Phelps retired, but for less than a year. During a vacation in Cabo San Lucas in the spring of 2013, several of his buddies proposed a handicap swimming race in the hotel lap pool. That race didn’t happen, but Phelps messed around alone in the pool. “Somehow I got the idea in my head,” says Phelps, who was then 220 pounds, 25 pounds overweight. “Maybe I’ll go again.” He called his mother and sisters. Debbie cried; she had always wanted to go to Rio. Michael called Bowman, who was less excited. “He called from Cabo, and he was obviously having a good time that night,” says Bowman. “He said, ‘I think I’m going to do one more.’ I said, ‘Absolutely not.’ I still had a bad taste in my mouth from dealing with him [between Beijing and London].” A few months later the two had dinner at the Four Seasons hotel in Baltimore. Bowman softened. Phelps went into training again, but he put only one foot in the pool. His lifestyle didn’t change significantly.

Phelps liked to gamble: mostly poker, but sometimes horses. He enjoyed drinking alcohol. Friends and family were concerned, but none, except possibly Bowman, felt that Phelps’s behavior had become so extreme that he was in danger of harming himself or others. “It’s not like he was spinning out of control,” says Steve Skeen, a lifelong friend who works as a math teacher in the Baltimore school system. “I thought the gambling was actually calming down a little. There was definitely a lack of direction on Michael’s part.”

Shea says, “There were some red flags, some lifestyle changes. And if Michael wanted to be distracted, it was easy for him to find partners in crime.”

Phelps says, “If I wanted to go out, there was no shortage of people I could text and find somebody to go with me.”

“Stevie [Skeen] and I got those texts,” says Shea. “We all did. We’re nine-to-five guys, so we’re not doing much during the week. Look, Michael is a stubborn guy. If he wants to so something, he’s going to do it, and unfortunately he could find people who just wanted to say they were hanging out with Michael Phelps, and they didn’t have his best interests in mind. There’s no way Stevie or I would have let Michael drive that night. But it was what? A Monday night? Come on, Monday night. But when I got the call about the DUI, I can’t say it was the most shocked I’ve ever been in my life.”

Phelps drifted away from his family. “I would call, and he wouldn’t answer,” says Debbie. “I was afraid something was brewing.” Flickinger, Phelps’s older sister, would occasionally see her brother and says, “He would be on edge. I was concerned, but there really wasn’t a way to voice that concern. I would text and get a cranky text back.’’

On the weekend before his arrest, Phelps had visited Johnson at her home in Southern California. They had met at the ESPY Awards in 2007, when Johnson was an ESPN intern assigned to cover Phelps. Both were 22 years old. They began dating and stayed together through the 2008 Olympics before breaking up later that year. They got together again at the end of ’10 but split up a year later. Johnson sent Phelps a single text congratulating him on his London performance. In the spring of ’13, Phelps reached out to Johnson and said he wanted to get back together. Again. “I said, ‘No, you don’t,’ ” says Johnson. “ ‘You just want to do what you want to do. I don’t want to waste my time.’ ” Phelps reached out to Johnson’s mother, asking for another chance with her daughter, and in the summer of ’14, Johnson flew to Baltimore for a weekend. Sitting in the Arizona State weight room as Phelps trains, Johnson struggles to explain. “We missed each other,” she says. “We had both had different relationships, but we never found anybody who understood each other the way we did.”

Before leaving the casino on the night of his DUI, Phelps called Johnson. Just a few minutes later he texted that he was sitting at a stoplight with a police car behind him. The next contact came an hour later, after Phelps had been arrested.

****

People who have visited The Meadows say it is a lavish place, beautiful and expensive, an oasis in the desert. The splendor hides a more spartan purpose. Patients are allowed no cellphones and no Internet access. Their days are tightly scheduled, including daily group and individual therapy sessions that require a type of introspection and sharing that had been foreign to Phelps. “When I got there, I was completely walled off,” says Phelps. “I didn’t want to talk to anybody.”

On one of his first nights, some patients were watching a football game in a common room. There was a cutaway during the broadcast of scenes of Phelps swimming and the news that he had not only been suspended for six months by USA Swimming but also banned from participating in the 2015 world championships. “I knew I was going to get suspended,” says Phelps. “I didn’t know they were going to take worlds away. I didn’t know that was even an option. Everybody in the room looked over at me. I said, ‘Yup, that’s me. Cat’s out of the bag.’ I stood up, walked over and got a drink of water, sat back down. ‘Yup, that’s me.’ ”

About five days into his stay, Phelps says, he began to loosen his resistance. He started to view his rehab as a competition. “I thought, O.K., I’m going to go with this. I’m here for 45 days, let’s see what I can get out of it.” The walls, decades in the making, began to crumble.

“I wound up uncovering a lot of things about myself that I probably knew, but I didn’t want to approach,” he says. “One of them was that for a long time, I saw myself as the athlete that I was, but not as a human being. I would be in sessions with complete strangers who know exactly who I am, but they don’t respect me for things I’ve done, but instead for who I am as a human being. I found myself feeling happier and happier. And in my group, we formed a family. We all wanted to see each other succeed. It was a new experience for me. It was tough. But it was great.”

Phelps began rising at six each morning to lift weights, do push-ups and crunches, and swim in the tiny pool. “I could take about one stroke and then I was at the other side,” he says. He was allowed to make phone calls each night. People on the other end—Johnson, Debbie, his sisters, Lewis—heard the voice of a man transformed. “You could tell that he had peeled back layers that had been there a long time,” says Hilary.

The deepest layer involved Phelps’s relationship with his father. Debbie and Fred were high school sweethearts who married in 1973 when both were in their early 20s. They split up in ’94 when Michael was nine and his sisters were teenagers. “For me, not having a father always there was hard,” says Michael. “I had Bob and I had Peter [Carlisle], these guys who acted as father figures. But deep down, inside, it was really hard. That was something that was a struggle for me to talk about for a long time, even with friends or my mother. Getting that off my chest in therapy was this huge weight off my shoulders.”

Phelps’s fourth week in treatment was family week—patients can invite people to come to The Meadows and participate in therapy with them. Phelps asked Johnson, and his mother and father. “I invited my father, hoping he would come,” says Phelps. “But not knowing if he would come.”

Throughout his son’s career, Fred Phelps had rarely done interviews. “Plenty of people called, came to my house,” he says. “Looking for dirt, I guess. I just refused to talk. This was never about me. It was always about Michael.” For this story, Phelps asked his father to speak to Sports Illustrated. Fred responded to a text message requesting an interview like this: “My pleasure. Happy to do it for Michael.”

Fred is 65 years old, a tough man shaped by his time in two uniforms: the one he wore as a high school and Fairmont State football player, and the one he wore as a state trooper. He described a recent autumn Saturday as “the kind of day that makes you want to put the pads on again.” As difficult as it was to be the adolescent son of divorced parents, it was also difficult to be the divorced father of three children. Mostly, Fred remembers a divorce that was inevitable, and then trying the best he could. “I bought a boat specifically to do things with the kids,” he says. “The girls never ended up liking the boat very much, but Michael and I went fishing all the time, caught rockfish out on the Chesapeake. We went to ball games. It was wonderful. What happened after that, I couldn’t tell you. I felt like Michael started to look on me as some sort of ogre. We started to separate.”

Fred remarried several weeks before the Sydney Olympics and brought his new wife to the Games, a misstep. “That surprised Michael,” says Debbie. “As a single mom, I tried to keep the family going, and to provide opportunities for Michael and his father to be together. One was not able to forgive, and the other one was upset.”

“We went up and down,” says Fred. Once, in 2001, he told Michael he would be at a swim meet in Annapolis, but he missed the meet because his shift relief couldn’t make it in to work. “Michael broke a record that night, and he didn’t want to hear any excuses from me,” says Fred. In ’08, Fred missed the Beijing Olympics because his second wife was dying of cancer. (She died in ’09.) In ’13, when Fred married for the third time, he and Michael were in a relatively cordial period. Fred asked Michael to be his best man. “He said no, and went in the opposite direction,” says Fred. “I thought, What did I do now?”

Father and son weren’t communicating at all when Michael put Fred on his invitation list for family week at The Meadows. On Oct. 27, 2014, Michael saw his father arrive and embraced him. “He said, ‘I didn’t know if you would come,’ ” says Fred. “I said, ‘You’re my son. Why wouldn’t I come?’ ”

There were things that Michael needed to say. “I felt abandoned,” he says. “I have an amazing mother and two amazing sisters. But I would like to have a father in my life, and I’ve been carrying that around for 20 years. That’s a long time. It does something to you. To a kid, especially. Right now I’d like to be able to talk to my father and have him be able to talk to me. Is my family perfect? Far from it. My parents had issues where they thought it was healthy to split. It wasn’t ideal. It wasn’t easy. But what we went through as kids made us as strong as we are. And now my father and I communicate. It’s not fixed. You don’t fix something like that. But it’s better.” Fred has embraced a second chance to be his son’s father and clings to it. “I have a better sense of who Michael is now,” he says. “And I think he knows I’m not an ogre.” At the end of our interview, he says, “The one thing I would so deeply ask of you is, please don’t write anything that would harm what my son and I have now. Please.”

Michael emerged from rehab with a fresh hunger for life. “I was just happy,” he says. Cynics will wait to see if it takes. It’s been more than a year, unabated. He continues with therapy, both in person and via phone. Friends say he has become more spiritual. Last March he went to Pueblo, Colo., for the funeral of Johnson’s grandmother, and near the end of the 45-mile drive back to the Olympic Training Center, John Legend’s “All of Me” came on. It’s their song. Phelps pulled over, proposed to Johnson, gave her the ring they had picked out and tackled her into the spring snow. They will be married after the Olympics. Phelps has also drawn strength from close friend, training partner and 2008 and ’12 Olympian Allison Schmitt, who last spring went public with her fight against depression.

Phelps guarantees that Rio will be his last Olympics. Tokyo 2020? “No shot,” he says. He remains active in outside ventures: the Michael Phelps Foundation, which he launched with his $1 million bonus from Beijing—to promote water safety and promote swimming as a healthy activity—has attracted more than 15,000 participants in the U.S. and around the world. In ’14 he founded the MP line of swimwear and equipment. He has many other sponsors, including Baltimore-based apparel company Under Armour. Also: “We want to have a family,” he says. “We want to have kids.”

Eight lanes of swimmers are grinding through an evening interval workout at ASU’s Mona Plummer Aquatic Complex; Phelps is in the second lane from the wall, doing a series of 10 50-yard breaststroke repeats with decreasing rest between the intervals, until the final two 50s are done essentially on top of each other. Two other swimmers are also doing breaststroke, three are swimming butterfly and two are swimming freestyle. Bowman is at the side of the pool with strength and conditioning coach Keenan Robinson, who has worked with Phelps for many years. It is a tough, high-quality session. After the 10th repeat Phelps asks Robinson to test his lactate level, which is commonly done to measure an athlete’s recovery time. Bowman tells Phelps to swim the 500-meter cooldown and then get his lactate level tested.

Phelps shouts at Bowman, “Sure, I guess we don’t need accurate stats. It’s bulls---. I’d like to see exactly when my lactate clears. Now we’ll never know.”

Bowman: “Yeah, think how good you could have been if you hadn’t had to overcome all this bad coaching. You know, we’d hate to keep doing the things that produced 22 Olympic medals.”

Phelps: “Maybe we’d have 24.” (In addition to a fourth in the London 400 IM, Phelps finished fifth in his first race, in 2000.)

Bowman: “The first one you screwed up. You went out too fast.”

Phelps (now laughing): “O.K., I’ll take that one, but you get the 400 IM from London.”

Bowman: “O.K., fair. I’ll take that one.”

The exchange had started with a real edginess and dissolved into comedy, chops-busting between old friends. They have the type of relationship that is unique to individual sports: Bowman is both coach and employee. (Phelps pays him.) But both men have been rejuvenated by Phelps’s recent transformation. From roughly 2002 to ’08, Bowman saddled Phelps with a workload that averaged 85,000—90,000 meters per week. At least once, says Bowman, Phelps went over 100,000 meters in a single week, and every week included a punishing mix of endurance and speed, because you don’t win all those medals on talent or race-day chops alone. Miles swam much earlier carried Phelps in London, but now he is training with purpose again.

“I’ve seen the ups and downs with Michael,” says Kalisz, who has been training with Phelps since 2009. “Sometimes you would see the passion, sometimes not. Now you see that guy every day.”

Bowman never expected to see that guy again. And last spring, even as Phelps trained relentlessly, his workout times lagged. “It had been so long since Michael and I did this the right way,” says Bowman, “I wondered if maybe I had forgotten how to do it.” Three weeks before last summer’s nationals Phelps swam five 150-meter butterfly repeats, a grueling workout that he had never done before. “He was always afraid to do it,” says Bowman. This time Kalisz crushed Phelps, but Phelps finished it. A week later Bowman put Phelps through a series of 100-meter butterflys, and each repetition was to be faster than the one before it. Phelps swam his last 100 in 50-meter splits of 29 and 27, one of the best sessions of his life. The San Antonio breakthrough followed.

Bowman has modified Phelps’s program to accommodate his advanced (swimming) age and his dodgy (but structurally sound) right shoulder. Instead of swimming 85,000 meters a week, he swims 50,000–60,000, still high-volume but not as high as it once was. He needs—and is allowed—more recovery from tough sessions. “My goal now is to have the speed and quality,” says Bowman, “but make sure he can recover fast enough to keep it continuous.” When Phelps was younger, he lived largely on his cardiovascular engine and stroke technique. At age 30, and with lower training volume, the engine is a little less potent. (After a recent 3,000-yard ladder session Phelps’s pulse rate dropped more slowly than the younger swimmers’ in the group; Phelps shouted, “Old man can’t get the heart rate down!”) But he is stronger and gets more power from each stroke, a different way of getting to the same place.

Phelps’s greatest gift now sits atop his shoulders. He no longer performs to fulfill historical imperatives but for his own, rediscovered joy. He stares across an Arizona street in the midday sun. Rio is nine months away; expectations will come knocking soon, but now he is prepared. “I’m back to being the little kid who once said anything is possible,” says Phelps. “You’re going to see a different me than you saw in any of the other Olympics.”

He digests the words and then enforces them: “That’s the way I see it.” His head bobs slowly up and down. A familiar face. But a new man.