Nico Hernandez carrying Tony Losey's memory with him at Rio Olympics

RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil — Tony Losey would have been here. Lewis Hernandez is sure of it.

It is Sunday, the second day of the 2016 Olympic Games. Lewis is sitting outside the small condo he is sharing with his ex-wife Chello this week, Lewis gets his coffee off the stove and sits back down at the small mosaic table. Beyond the gravelly driveway, a breeze slams a wooden gate shut. Dogs bark next door.

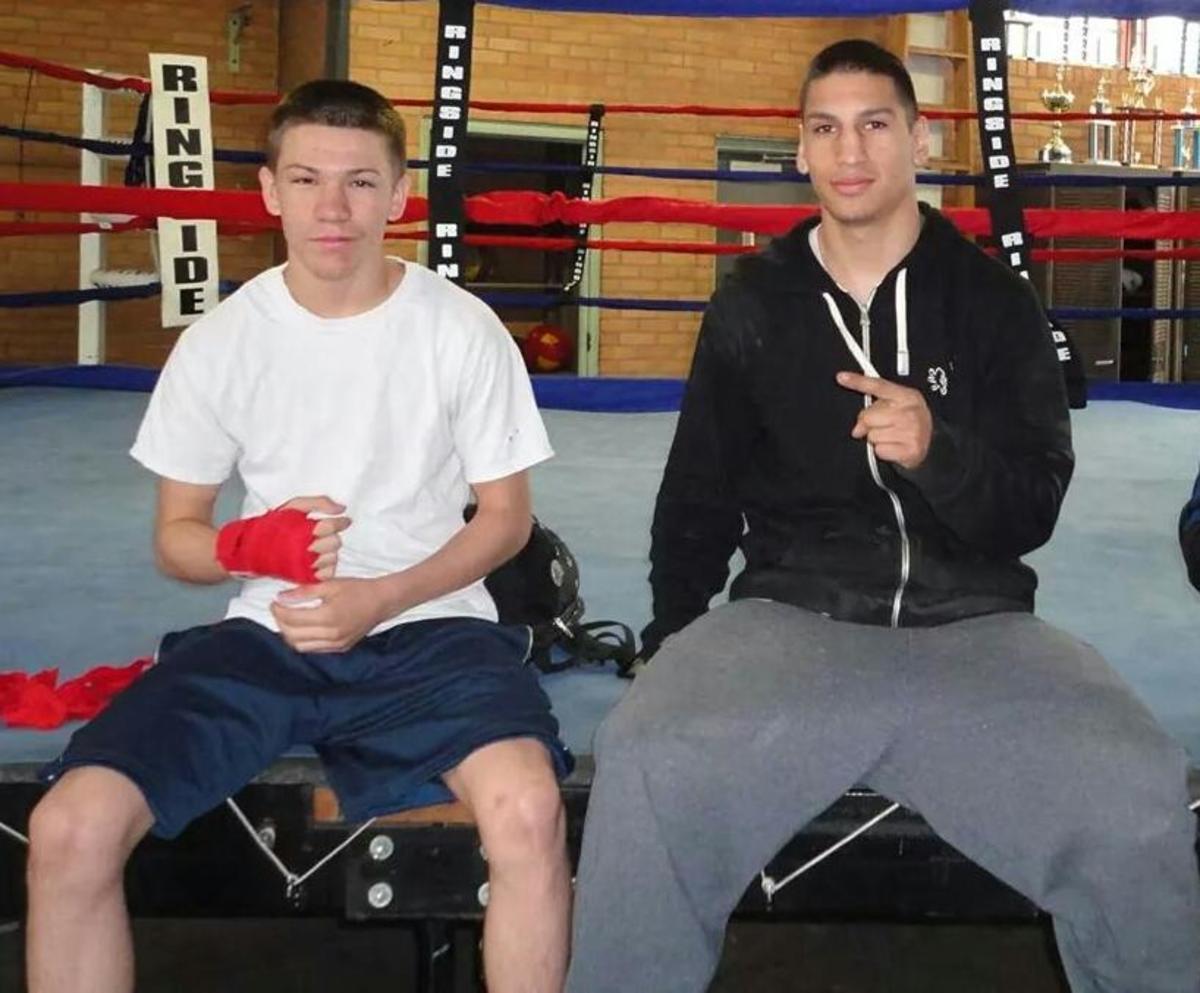

Just a few miles away, Nico Hernandez will try to win a boxing medal for the United States. Lewis trained Nico, in Wichita, Kan., and he trained Tony there, too. Lewis says that if Tony hadn’t died two years ago at age 22, he would be here in Rio, a southpaw welterweight, fighting for the United States.

“No doubt about it.”

Tony Losey is here. Can’t you see? His picture is on Lewis’s shirt, which reads IN MEMORY of Tony Losey 1991–2014, and Rest in Paradise. And Nico, a light flyweight, swears that Tony is with him whenever he enters the ring. After Nico won his first match here Saturday, he sat in the stands with his father and said his legs felt tired, and he couldn’t figure out why. Nico’s legs never feel tired. But Tony’s always did.

“That was Tony here with you,” Lewis told Nico, laughing. “That’s what that was.”

Michael Phelps, Usain Bolt intertwined as pillars of modern Olympic greatness

Tony Losey is not here. This reality hits Lewis and Nico Hernandez at different times, in different ways, but it hits them every day. Nico’s voicemail message used to make Tony laugh. Lewis’s ringtone reminds him of Tony. Nico says Tony was his best friend. Lewis says Tony was like a son.

What happened to Tony? Well, the end came suddenly, and far too soon. The beginning was rough, shaded by brutality. But in between … well, in between there was something surprising and beautiful, a triumph of human decency from a boy who seemed incapable of it. Let’s begin there.

When Nico Hernandez was nine years old, he was desperate to compete in a sport that would scare most men. His uncle boxed. His dad helped train his uncle. Nico begged his father to let him fight. Lewis worked 60 hours a week as a truck mechanic, but he also worked with Nico at Northside 316 Boxing Club, and he said OK.

Tony Losey was 14 then, and he came to Lewis Hernandez with the same request, from a different angle: Train me. Tony had boxed before, but his technique was sloppy and his life was already out of control. People said he was a thief and a thug, that he got into fights and carried guns. They were right. Lewis says he was “not a bad kid,” but later, multiple times, he says simply: “A bad kid.” Many people had given up on Tony. Lewis agreed to train him.

Nico got a bloody nose on his first day in the ring and was hooked. He ran four miles a day from the time he was nine years old. He won his first 25 fights. He was quiet when he stepped in the ring and exuberant when he walked out.

Tony was loud on the way in. Before matches, he would tell his opponents’ girlfriends: “I’m going to knock your boyfriend out.” People on the boxing circuit did not like him. They wanted him punished. He kept winning, but he also kept getting in trouble. Lewis kept training him.

China facing an uphill climb to reclaim its place as a world basketball power

Nico and Tony shared a love for the sport that most people wouldn’t understand. If nobody in their weight classes was available to fight, they would beg to fight larger, older boys.

“They would get mad: ‘Why can’t I fight that guy?’” Lewis said. “‘Man, that guy is 50 pounds heavier.’ ‘I don’t care!’ They got mad. It was like you killed their mom or something.”

Tony got a tattoo of an angel and a devil, and while it sometimes seemed like he couldn’t tell the difference, Nico knew better. Tony would insist that Nico stay far away from drug dealers. They laughed at TV shows together. They were five years apart, with very different reputations in Wichita, but they were best friends.

Still, the devil pulled. Tony got in so many fights—street fights, not boxing matches—that Lewis says, “A lot of times, I wouldn’t let Nico go [out] with him. He was always in trouble.” In 2007, Tony’s brother, Javier Rizo, shot a man as part of a robbery; Rizo pleaded guilty to first-degree felony murder as a juvenile, so he could avoid adult prosecution, and went to prison until he was 22.

Table tennis player Kanak Jha's performance in Rio just a glimpse at what's to come

In 2011, the year he turned 16, Tony received two years probation for an aggravated-battery case. But before his senior year in high school, Tony moved in with the Hernandezes. He would go to class; he would box; he would save the rest of his life from the streets. Lewis liked what he saw. Then Tony’s brother Javier was released from prison and begged him to go out and celebrate. Tony had two days left on his probation. He wasn’t allowed out late and wasn’t allowed to drink. He went anyway and he drank.

That night, cops tried to pull Javier over, and Javier (who was also not allowed to drink, and was also drinking) did not want to go to jail again. Javier sped through the Wichita streets until he hit a 34-year-old woman. He and Tony fled.

The next day, Lewis confronted Tony. Tony admitted he was out with his brother, and his brother got into an argument with his girlfriend and led the cops on a chase, and Tony told his brother to slow down, but Javier had kept going and hit a woman.

Lewis told him the woman was dead. Her son had also been a boxer at Northside 316. Tony cried.

Tony thought about telling police he had been behind the wheel himself, to take the fall for his brother and keep him out of jail. Lewis was furious. Tony’s life was Tony’s; he shouldn’t throw it away because his brother was reckless.

Tony took Lewis’s advice. Javier was convicted of murder and sentenced to life in prison, plus 89 months.

USA swims for silver: DiRado, Ledecky the early headlines at Rio Olympics

Tony kept boxing, and Lewis noticed something else: He stopped getting in trouble. Tony had two young daughters and a fiancée, and he was committed to living the life he wanted to live when he was 14 but didn’t know how.

Tony got a job as a sandblaster. He committed himself to his sport. He rose to USA Boxing’s No. 3 ranking among welterweights. He told Nico: We’re going to win gold medals at the Olympics. He was training for an Olympic qualifier and working as a subcontractor at a steel fabricator when a 12,000-pound tank shifted, rolled off two sawhorses, fell on Tony and killed him.

It was Sept. 2014. Lewis and Nico were so stunned that they kept going back to the spot where the tank fell, every day, for more than a month, just because they missed Tony.

Boxing as a canal to redemption is a 20th-century story. We know too much about blows to the head to recommend the sport to a child; if young Cassius Clay showed up to a Louisville gym today, somebody would hand him a basketball. But Lewis believes the sport taught his son Nico discipline, and he believes it saved Tony Losey’s life.

Tony Losey lived 22 years—not nearly as many as he deserved but more than he might have if he had never asked Lewis for help. Nico Hernandez will carry his memory into the ring Monday, when he tries to upset the second-ranked boxer, Russian Vasilii Egorov. And as Lewis Hernandez sat with his cup of coffee next to that driveway here Sunday, 5,000 miles from Wichita, he said he thinks about Tony every day, and he said, “Everybody that knew Tony, after the good kid he became … they felt the love that Tony gave,” and then he cried.