For Michael Phelps, Rio marks the end of storied career and transition to new life

This story appears in the August 22, 2016 issue of Sports Illustrated. To subscribe, click here.

The transition to another life began even before the final race. Michael Phelps awakened last Saturday morning in Rio de Janeiro, shocked by the force of his emotions. It had been a long and harrowing ride: He had swum in the Olympics at age 15, and he had won eight gold medals at 23. He had been publicly embarrassed numerous times by his own misbehavior, and he had desperately corrected his own life at 29. He became a father and soon will be a husband. At age 31, he had already won four gold medals and one silver at what he had promised repeatedly would be his final Olympics, and the weight of that finality chased him with more persistence than most of the swimmers he has beaten over the many years of his career.

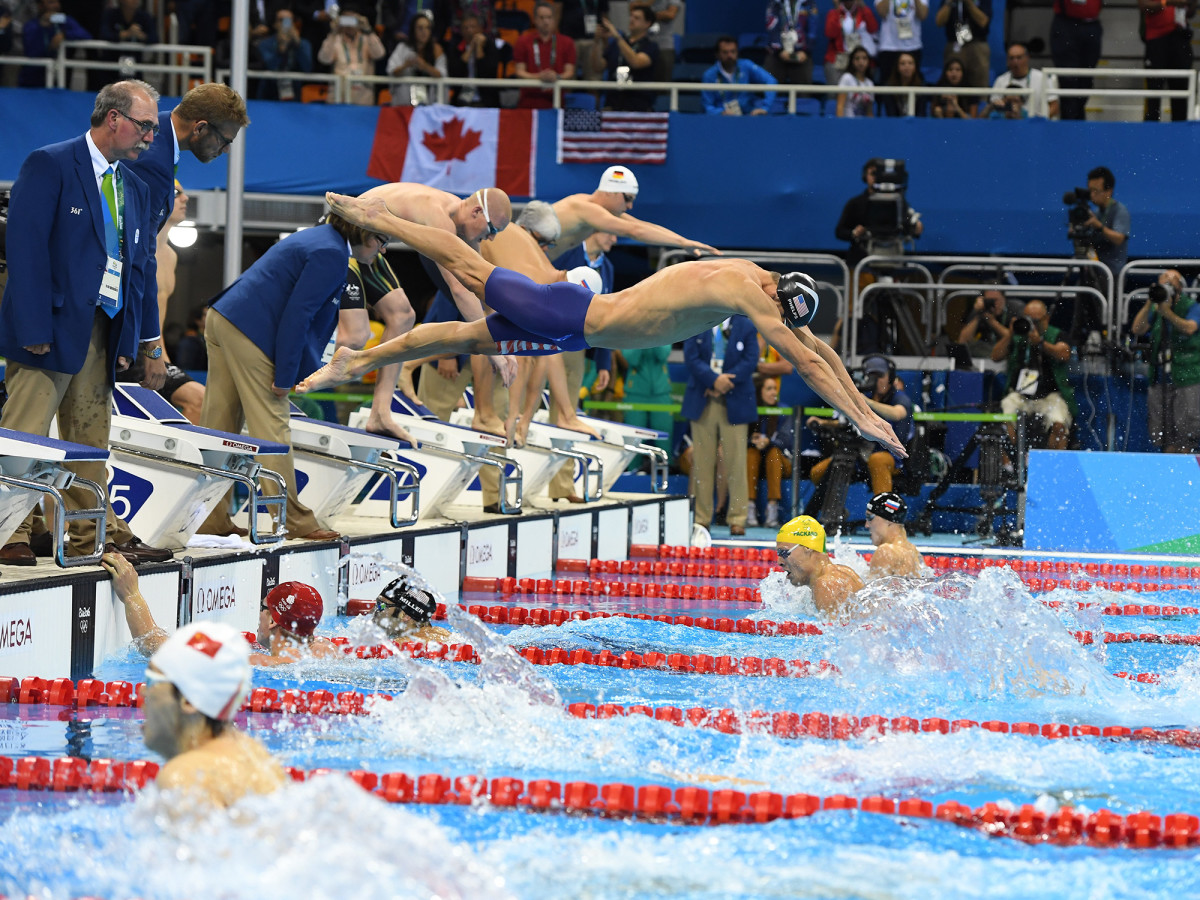

His final race was Saturday night in the 400-meter medley relay, swum in the late evening at the Olympic Aquatics Stadium, where Phelps had raced all week as if reborn. He started that night by swimming laps in the warmup pool and finished by walking a victory lap with his teammates after they received their gold medals. “The entire time I felt like I was on the edge of breaking down,” said Phelps. “And not just tearing up, but breaking down to the point where my whole body would be shaking from crying so hard.”

In Rio he won two of his three individual events and participated in three gold-medal-winning relays, running his career total to 23 gold medals, three silver and two bronze, far more than any other Olympian. “It’s insane, right?” he said on Sunday afternoon in an interview with Sports Illustrated. “I’m still kind of trying to wrap my head around 28 medals.”

It is tempting to frame Phelps’s medal haul as just the latest—if closing—chapter in an unparalleled career. “Michael’s performance in this meet, he showed that he is the greatest swimmer in the world,” said Laszlo Cseh of Hungary, a longtime rival who tied with Phelps (and Chad le Clos of South Africa) for the silver medal in the 100-meter butterfly. Then Cseh added, “Still.”

Sports Illustrated brings the stars of the Rio Olympics together for exclusive cover shoot

But Rio was not just the last step in a longer career for Phelps. It was, in many ways, the first step of the rest of his life, even if it took place in a swimming pool. The setting was familiar, but little else was. Phelps’s mother, Debbie, was in a poolside seat, as ever, but so was his fiancée, Nicole Johnson, and their three-month-old son, Boomer, who was bedecked in red, white and blue and wearing headphones to protect his ears from the din.

Phelps’s opponents were from generations behind his. Joseph Schooling, who represents Singapore but has lived in the U.S. since 2009 and competes for Texas, defeated Phelps in the 100-meter butterfly. Immediately a photo of the 13-year-old Schooling posing with Phelps in 2008 went viral. “Michael is the reason I started swimming,” said Schooling. It is a common story in the sport.

Six thousand miles away, in Maryland, Phelps’s father, Fred, watched the Games on television. Fred and Debbie Phelps split up when Michael was nine, and Michael was scarred by the divorce. As he became a superstar and struggled to find traction outside the water, he had only a superficial relationship with his father. That changed in the fall of 2014, when Michael went into rehab after a drunk-driving arrest. He invited his father to visit him at the facility in Arizona, and there the two men rebuilt a bond. Fred was in Omaha in late June for the U.S. trials, but he couldn’t make it to Rio. “A lot of factors involved,” he said in a text message before the Games. “I’d love to be there, though.”

Fred hadn’t been to an Olympics since Athens, in 2004, but this absence was bridged by an evolving love. “We were texting throughout the Games,” said Michael. “He was counting down my races; he wanted that 200 IM real bad. [Phelps won.] Our relationship is really great, and it’s continuing to grow. We’ve learned that we have a lot in common.”

This, too, was different for Phelps: He found his best condition only in the last few weeks leading up to the Games. After seven weeks of training at high altitude in Colorado Springs, he swam at a meet in Austin the first weekend of June. “He didn’t swim well in Austin,” said Bob Bowman, Phelps’s longtime coach. “At that point, I was feeling pretty pessimistic about things.” Phelps then won three events at the trials but did not swim particularly fast. “I didn’t know if he would make any of our relay teams,” said Bowman. “And in the individual events, I thought maybe he could win a medal or two, not necessarily gold.”

Bowman tried to persuade Phelps that rest would set him up for the Games. Phelps was skeptical. But at a training camp at Georgia Tech a rested Phelps swam a 100-meter freestyle relay split in 48.5 seconds, behind only Nathan Adrian, who won bronze in the 50- and 100-meter freestyles in Rio. “After that,” said Bowman, “I didn’t have to convince him anymore.”

It was the last, validating test of their long relationship. Medals followed, until Rio felt a little like Athens or Beijing—but not like London, where Phelps was undertrained and vaguely uninterested. “Hate to say this,” he said Sunday, “but in London I was going through the motions.”

Usain Bolt provides moment of pleasure for track and field, Olympics with 100m gold

So Rio was not just a validation of Phelps’s dominance but also a proper farewell. London ended with a shrug, Rio with a loving embrace. “In London I just wanted it to end,” Phelps said on Sunday. “Here I enjoyed the entire Olympics. It’s a completely different feeling.”

Something else is different, too. Had this been 2012, Phelps surely would have had at least a few beers in celebration. But after his stint in rehab he decided not to drink. He never said never, but he says he has not had alcohol since the fall of ’14. “Before, I was looking forward to celebrating that way,” he says. “Now I look forward to celebrating another way. I said all along, maybe I’ll have a beer again, maybe I won’t. But I’m not looking forward to getting on a plane and going to X-Y-Z and throwing a party. I’m looking forward to spending time with Nicole and the little guy.”

Soon enough, although not too soon, Phelps will be faced with filling the long hours that he spent swimming laps. He insisted again on Sunday that his retirement decision is final. (Bowman said, “I have no doubt that he could come back and win medals. But at some point enough is enough. Is 25 gold medals really going to be better than 23? I suppose it is. But how much better, and what’s the point? He’s done what he’s done in the pool. It’s time to move on.”)

Phelps will continue to live in Scottsdale, Ariz., where he trained for the Olympics while Bowman coached men’s and women’s swimming at Arizona State. Phelps will assist Bowman in some capacity, but beyond that, his retirement plans are nebulous.

Michael Phelps on retirement: 'This time I mean it'

Broadcasting is a possibility: Phelps is a swimming nerd at heart, with an encyclopedic knowledge of the sport, and there would be no bigger name to sit in NBC’s booth. “I wouldn’t turn it down,” says Phelps. “[NBC analyst] Rowdy [Gaines] has said these could be his last Olympics and that I could take over for him. It’s something I’ll think about in the future.”

Phelps has a foundation that expands kids’ opportunities to participate in swimming, and he has sponsors. Undoubtedly he will be in demand as a speaker. “I will stay connected to the sport,” he says. “It’s been a part of my life forever. One thing I know is that I won’t let my weight get up to 230 pounds [as he did between the 2008 and ’12 Olympics]. And Nicole and I are looking forward to finding a new life together.”

The question remains: Will he find enough diversions to fill the void left by giving up swimming? “Time will tell,” says Bowman. “Right now, he’s in such a good place. I think he’s made the right exit. I think he’s going to be at peace.”

On Saturday night Phelps lay in bed with Nicole, and the two of them cried together. “We both said, ‘We did it,’ ” says Phelps. “We did it together.” His career will outlive him by decades, swimmers invoking his name as long as there is water in Olympic pools. He leaves wanting for nothing, secure in his past and present, confident in his future. “This is all I ever wanted,” he said. “And more.”