Earnhardt's courage on the track spoke volumes about the man off it

Even after the passage of 34 years, the crash remains among the scariest in the history of Atlanta Motor Speedway.

With 50 laps to go in the 1977 Dixie 500, the steering failed on a Ford driven by Dick Brooks. The car hit the outer wall in the third turn and caromed down the banking into the racing groove.

Dale Earnhardt, running only his third race at NASCAR's top level, had no time to react at the fast 1.522-mile track. He hit Brooks' car going full bore. Earnhardt's Chevrolet flipped five times, carrying all the way to the fourth turn. The car slammed hard onto the apron alongside that of Brooks.

Emergency crews worked several minutes to remove the two drivers from their demolished vehicles. Amazingly, Earnhardt and Brooks weren't seriously injured or worse.

In the press box, some reporters openly speculated that the accident was so frightening it would be the last they saw of Earnhardt in big-time stock car racing. They were wrong.

"I learned of Dale's bravery that very day in Atlanta," recalls driver Buddy Baker, a star from the 1960s through the '80s. "I finished fifth in that race and I asked about Dale and Dick Brooks the minute I got back to the garage area. "My team owner, Bud Moore, shook his head and said, 'You wouldn't believe that Earnhardt boy. Even after a crash that bad, he came to pit road after he was released from the infirmary. He was asking crew chiefs to use him as a relief driver. He wanted to go back in the race!'"

Thus began stories of Earnhardt's uncommon courage, which was to grow into legend.

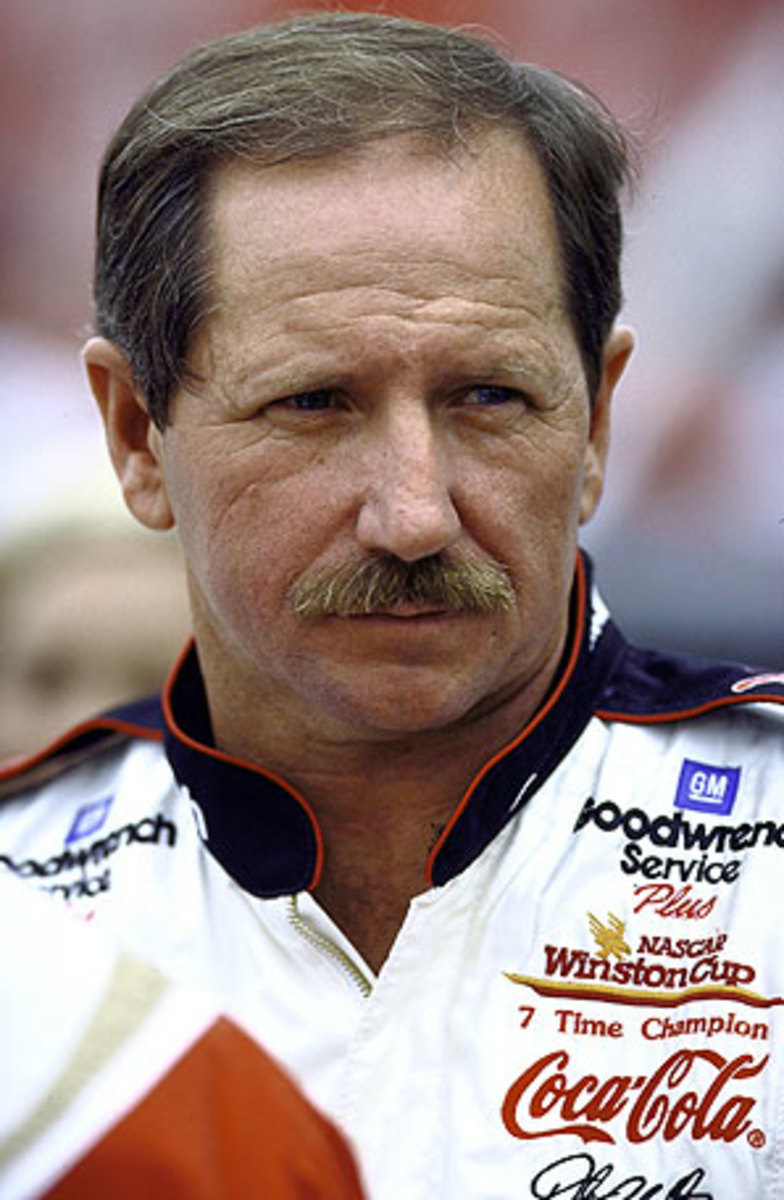

His fearlessness marked a colorful, sometimes controversial career that produced 76 victories and seven Winston Cup Series championships. The latter tied the once-considered-unapproachable mark of Richard Petty. Earnhardt, driven to capture an eighth title, lost his life in the effort. The fatal crash came on the last lap of the Daytona 500 on Feb. 18, 2001, 10 years ago.

Earnhardt, 49 at the time, suffered a basilar skull fracture in the accident that also involved Ken Schrader and Sterling Marlin. As the trio battled abreast for third place while entering the fourth turn they made contact. This sent Earnhardt's black No. 3 Chevy, owned by Richard Childress, nosing at an angle into the outer concrete wall.

The wreck didn't look too bad. Earnhardt had ridden through crashes that appeared far worse, often emerging with only bruises. However, three-time Cup Series champion Darrell Waltrip, an analyst on Fox Sports' telecast of the 500 in 2001, commented ominously, "I hope Dale is OK..."

As the crash that shook motorsports on a worldwide scale unfolded, Michael Waltrip and Dale Earnhardt Jr. swept to a 1-2 finish in cars fielded by the elder Earnhardt.

Over the ensuing 10 years a question has persisted among some NASCAR fans. "Was Dale Earnhardt trying too hard to make that 500 something of a personal sweep by finishing third?"

I began writing about Earnhardt in May 1975, when he practiced in a borrowed car for his first NASCAR big-time start in Charlotte Motor Speedway's World 600. As Earnhardt's career grew, I came to learn that for him there was no such thing as "too hard." He hated, for example, the restrictor plates that limit horsepower and usually keep speeds under 200 mph at Daytona and its companion track, Talladega Superspeedway in Alabama. He lobbied aggressively, to no avail, for abolishment of the plates. It's telling that Earnhardt triumphed 10 times in 500-milers at Talladega, six more than anyone else.

"While a lot of drivers were seeking slower, Dale always -- ALWAYS! -- wanted to go faster," recalls Baker, himself a foe of the restrictor plates and who now hosts a twice-weekly motorsports show on Sirius radio. "In the testicles department I doubt that anyone in NASCAR ever has had them like Dale, except maybe Junior Johnson and Curtis Turner back in the old days."

Earnhardt perhaps most famously displayed his disdain for danger during the Daytona 500 of 1997. On the 189th of the race's 200 laps, Earnhardt was battling for the lead in a pack that included Jeff Gordon, Ernie Irvan and Dale Jarrett. As the drivers roared off the second turn onto the backstretch of the 2.5-mile track, the cars of Earnhardt and Gordon scrubbed fenders. The contact sent Earnhardt tumbling down the track, landing in a grassy area between the asphalt and the infield's Lake Lloyd. The car landed on its wheels and the unhurt Earnhardt got out on his own. He walked to an ambulance for a mandatory ride to the infield infirmary.

"I got in the ambulance and looked over to where the car was sitting," he revealed after the race. "I said, 'Man, the wheels ain't knocked off that thing!' I got out of the ambulance and went back to the car. A guy, part of the wrecker crew, was inside it and they were starting to tow my car away. I told him to flip the ignition switch. The engine fired back up. I said, 'Get out! Give me my car back! I gotta go!' "

Earnhardt climbed in and drove to his pit as fans thundered their approval. His crewmen went to work, tearing away loose sheet metal and taping back what parts they could. Then, to continuing cheers, Earnhardt drove the battered, taped-together Chevrolet back into the race. Even Dale's detractors, and there were many, conceded this was a gutsy display of grit.

Earnhardt was outright loathed by some fans, turned off by the aggression that sometimes left rivals spun out and stewing, especially if a victory was at stake. "The last guy you wanted to see in your mirror was Dale in that black car," Gordon often said. "Anyone who says it wasn't unnerving is fibbing."

Not surprisingly, then, that Earnhardt's nicknames, "The Intimidator" and "The Man in Black" came into being.

"When Dale was behind you, it was like having Darth Vader back there," remembers Earnhardt's friend and on-track foe Rusty Wallace. Wallace once became so infuriated after Earnhardt spun him out at Bristol, Tenn., he bounced an empty plastic water bottle off Dale's nose in a post-race confrontation on pit road.

Earnhardt developed such a heated rivalry with Geoff Bodine that NASCAR chief Bill France Jr. had to intercede. Ricky Rudd was another who frequently tangled with The Intimidator and was considerably less than an admirer. Rudd once memorably zinged Earnhardt when the top 10 drivers in the Winston Cup point standings gathered onstage in the Waldorf Astoria's grand ballroom during the postseason awards event in New York City.

"Backstage, all of us had shiny shoes until Earnhardt showed up," cracked Rudd. "Then he walked all over us."

While the give-no-quarter style frequently brought boos raining down on Earnhardt, many fans loved him just as passionately because of it. How great was his following? The morning after Dale died, thousands of fans gathered in front of the sprawling race shop he'd built just outside Mooresville. It's a complex that the witty Darrell Waltrip called "The Garage Mahal."

Many of these fans had driven hundreds of miles through the night to be there, bringing candles, caps bearing Earnhardt's likeness and name, flowers and model No. 3 cars to create a massive memorial display. Included in the crowd were two sisters from Memphis. There had been a family rift, and the siblings hadn't spoken in years. So traumatic was Dale's death to them that they reconciled immediately upon NASCAR president Mike Helton's confirmation that Earnhardt was gone. They rode to Mooresville together to mourn.

When Dale died, racing expired as well for an untold number of stock car racing fans, such as Barbara Hurst, 83, of Concord, N.C. "I quit watching the races on TV," she says. "It simply wasn't the same without that black No. 3 out there, and it won't ever be. How could it? I began going to races in the 1950s and Dale was the best ever."

Junior Johnson, noted for assessing talent after he retired as a driver in 1965 and who became a team owner who won six championships, agrees wholeheartedly. "Earnhardt was tops," says Johnson. "The best ever, bar none."

Bar none?

"Bar none!"

Will there ever be another driver like him?

"That's difficult to say, but I doubt it," continued Johnson. "Who knows what young kid is going to come along and blow the fields away some day? Earnhardt certainly was the icon of the century. I think Curtis Turner and LeeRoy Yarbrough were every bit as brave as him, but Dale had that extra something. He got so good that he could tease guys and play with them out on the track. He worked on 'em until he got the best of them.

"Among the current drivers I think Kyle Busch is closest to resembling Earnhardt in handling a car, but I strongly doubt he'll ever be his equal."

It's not widely known that when Darrell Waltrip left Johnson's team after the 1986 season, Junior wanted to hire Earnhardt as his driver. "But my sponsor, Budweiser, shot that down," says Junior. "Bud wanted no part of Dale Earnhardt, saying he was too controversial."

It's beyond ironic, then, that Budweiser paid Earnhardt millions to sponsor the team that he later fielded for Dale Jr.

The senior Earnhardt's steel nerve extended beyond race tracks. In 1990, Earnhardt had an angry confrontation that turned physical with a poacher on the farm where Dale made his home in Iredell County, N.C.

Late one afternoon in early December a worker at the spread near Mooresville heard a far-off rifle shot. He and Earnhardt went to investigate and found a trophy-sized deer had been killed and hidden in a patch of trees. Earnhardt staked out the spot, figuring the trespasser would return that night to get the buck with the big rack. Sure enough, the guy came back. An irate Earnhardt and the poacher came to blows. Earnhardt fractured his right hand with a punch to the man's jaw.

The incident occurred just before Earnhardt was to receive the trophy as Cup Series champion at the Waldorf Astoria. He had the cast on his hand painted black so that it would blend in with his tuxedo.

"Dale had no fear of anything," says a longtime friend, former service station owner Jerry Ramey of Mooresville. "When he accosted that poacher, he didn't know whether the man was carrying a gun or not. But he went after him anyway."

Earnhardt took chances even while playing mischievous pranks.

In 1990 I'd attended the annual UNOCAL Record Club dinner for pole winners at Darlington Raceway. It was a warm spring night and the aroma of azaleas was in the air. Leaving the event I put the top down on my little Pontiac Sunbird convertible. I tuned the radio to soft music for a pleasant ride at about 45 mph through the country back to a motel where the race teams and motorsports media were staying. Suddenly, something grabbed the left side of my neck. Imagine the shock!

Initially, I was too petrified to look at what might be putting such a sharp, painful squeeze on me. I thought, "Well, the Lord finally is punishing my sins, and they have been considerable."

Finally, I looked. There was Earnhardt, grinning broadly and wickedly. He was leaning from the passenger-side window of a Cadillac that Childress had driven abreast of my car, running alongside within inches. Earnhardt, foolishly, was out of the window to the waist.

After a few seconds he let go of me and, whooping in delight, slipped back into the Cadillac as Childress sped off into the night. I had to pull off the road for a couple minutes to calm down.

Back at the motel, Earnhardt and Childress were waiting for me, roaring in laughter. They wanted to see if I had wet my pants. I hadn't, but it was close.

In 1996, Earnhardt suffered a broken collarbone and sternum in a violent crash during the Talladega 500. The injuries limited him to just the first six laps in the following Brickyard 400 at Indianapolis Motor Speedway. As he relinquished his race car to relief driver Mike Skinner, Earnhardt had tears in his eyes. It was the only time that most people involved in NASCAR, including me, ever saw him cry.

"I think the only fear that Dale ever had was a fear that he might not get to race," says Bristol Motor Speedway executive Kevin Triplett, who once worked for Earnhardt.

Perhaps the greatest compliment ever paid Earnhardt came from rival driver Cale Yarborough, himself known for bravery and toughness.

After Earnhardt made an especially daring move to win the 1980 Busch Clash special event at Daytona, an appreciative Yarborough declared, "You couldn't castrate Dale Earnhardt with a chainsaw."