Dan Goldie's troubled youth, tennis career enabled his financial business

This story appears in the April 20-27, 2015, issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

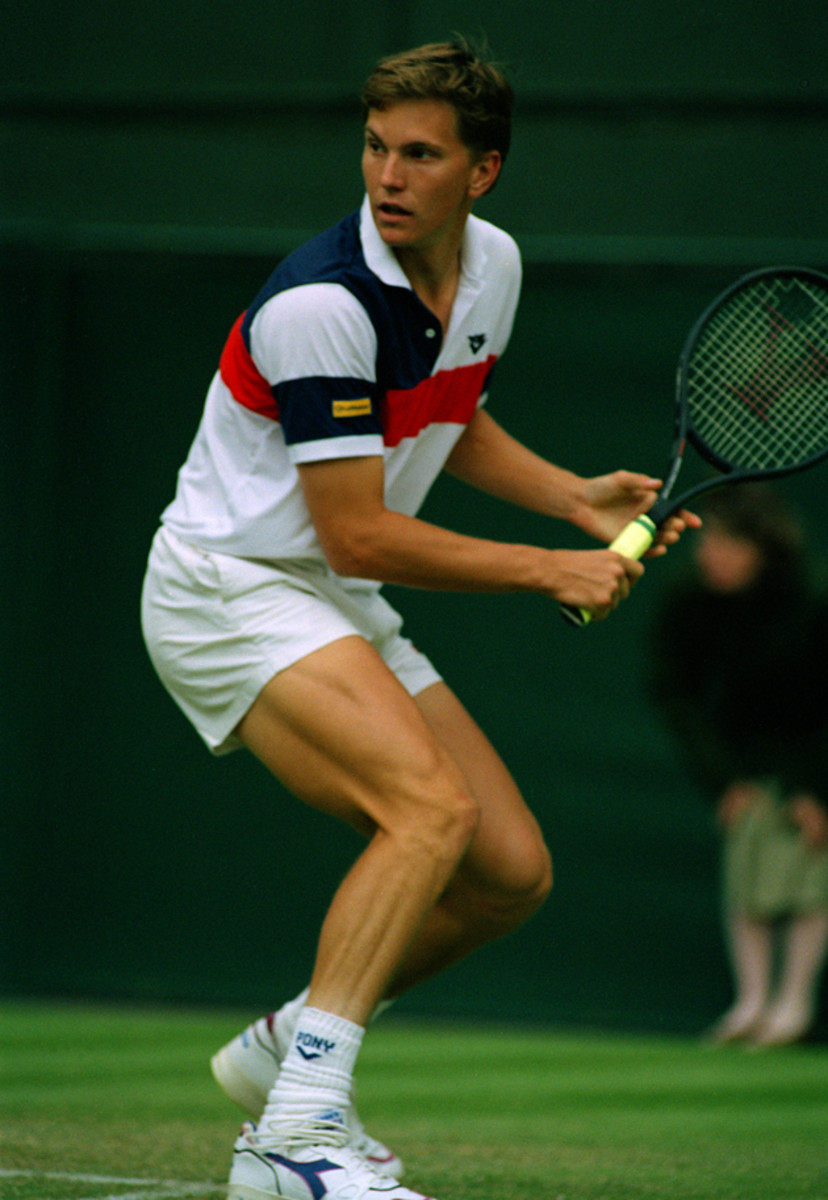

Dan Goldie’s pro tennis career spanned 5½ years, during which he won four titles (two in singles, two in doubles), reached 27th in the ATP world rankings (in 1989) and earned $683,000 in prize money—or less than one 1/1,000 of the money he now manages through Dan Goldie Financial Services in Palo Alto, Calif. For Goldie, 51, the two pursuits are linked because his sports career enabled his life as a financial pro.

Growing up in the 1970s in McLean, Va., he played tennis with a singular purpose: to escape a domestic life dotted with fear and poverty. "My father was an abusive alcoholic," he says. "I never wanted to go home. So what happened was, I engineered a way out of the situation—starting around age 12, when I began to realize I had a talent for tennis."

Goldie began competing and training nonstop, using each victory as fuel to power his escape. Three years later he emerged as the top 18-and-under player in the mid-Atlantic. Looking back, Goldie concedes that the competition "was relatively weak," but at the time it felt like a huge accomplishment.

If Goldie followed many of the other top young players of the era, he could have gone to the Bollettieri Academy in Bradenton, Fla., the tennis hothouse that would produce many of the opponents Goldie faced on the pro tour, such as Andre Agassi (against whom he went 0–3), Boris Becker (0–2) and Jim Courier (1–2). But Goldie's parents were divorcing; his dad was an unemployed engineer who died of complications from alcoholism in 1995, and his mother's income as a bookkeeper couldn't cover the academy's steep tuition. "We went from an upper-middle-class family living comfortably, to my mother and I living alone, paycheck to paycheck," Goldie recalls. That frightening experience, he says, "caused me to place a high value on financial security."

Goldie finally left in the fall of 1982, bound for Stanford on a full tennis scholarship. During his sophomore year Goldie's serve-and-volley style—a common approach at the time that was well-suited to his 6'2", 175-pound frame—earned him a spot as a practice player on the U.S. Davis Cup team. As a junior he won the Pac-10 singles and doubles (with Eric Rosenfeld) championships and the Intercollegiate Tennis Association National Indoor crown. In '86, his last year at Stanford, he was named an All-America for a third time and won the NCAA singles title, leaving with a record of 71–24.

Former Bengals tight end Tony McGee found post-NFL success with logistics

With that success as a springboard, Goldie immediately turned pro; he regretted the move almost as quickly. Although he could hold his own against top players—at Wimbledon in 1989 he beat Jimmy Connors in a second-round match—Goldie could just as easily lose to lesser lights. "I don't think I really loved the game the way the top players did," he says. "I made a mistake, personally, of being too focused on the earnings dimension of professional tennis."

Goldie’s fixation with money went beyond counting how much he was making. At Stanford he took business-school courses while earning a bachelor's degree in economics, and he later completed an MBA at Berkeley. While he played, Goldie traded on his stature as a tennis player to build relationships with top financial professionals, "trying to get a feel for what this industry is like," which gave him ideas about one day starting his own firm.

In 1991, suffering from bad shins, Goldie retired from tennis with a career record of 122–117. Three months later he launched an independent financial advisory firm. He began with no clients and a minimum buy-in of $50,000. Today his firm manages $700 million in assets for more than 300 clients, and the buy-in is $1 million.

Clients get plenty of guidance: Goldie helps them with retirement planning, college savings, insurance and more. But investment management is a central focus, and in that, he's closely aligned with Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA), a firm based in Austin. DFA runs mutual funds that eschew market timing and forecasting—factors that can make investing more erratic and more expensive—in favor of a quantitative process that spreads investors' money across a diversified range of assets. Goldie met with DFA early in his career and has been using their funds since. His clients, he says, "are basically exposed to the global market in a balanced way."

"Dan has a unique blend of focus, discipline and devotion to his clients," says David Booth, the chairman and co-CEO of DFA. "He has also demonstrated an uncommon ability to communicate the often complex ideas of academic finance in simple and intuitive ways."

George Foreman is fueled by a desire to never stop working-and earning

Goldie's approach to investing has brought him more acclaim than he ever found on the court. Barron's has twice named him one of its top independent financial advisers. It also inspired a how-to manual for which Goldie is perhaps now best known, The Investment Answer: Learn to Manage Your Money & Protect Your Financial Future. The book was a labor of love that Goldie cowrote with longtime client and friend Gordon Murray, a veteran bond salesman and managing director at Lehman Brothers who died of cancer in 2011 at age 60, two weeks before the book's hardcover release.

The book's central theme is the folly of trying to beat the market. But after Murray's death, that theme became secondary to the story of Murray, a Wall Street insider who found religion about the industry's misleading and risky ways thanks to a former tennis ace who introduced him to a new way of investing. The Investment Answer spent one month atop The New York Times best-seller list and has been translated into at least eight languages.

Goldie says the book's ideal reader is someone who "isn't interested in numbers or money but really needs to know this information." Athletes often fit that description. "They've got all this money and all these people wanting stuff from them and telling them what to do—that's why there are so many bankrupt former athletes," adds Goldie, whose clients include a handful of former touring pros.

This September, Goldie plans a rare return to the court: He'll play in an exhibition for only the second time since his retirement, at a charity event at Stanford. Thanks to advances in equipment, Goldie says, tennis feels "challenging and fun" again, and completely different: "Sometimes I feel like I am playing Ping-Pong." But he'll never regret leaving the game as early as he did. "I get a lot of psychic value today from helping people become and stay financially sound," Goldie says. "It is the primary reason I do what I do."