Carlos Alcaraz Is Ready

The crowds at Wimbledon’s Centre Court tend to represent the moneyed class, the winners in the modern economy. And this was especially so on the third Sunday in July. The fans included all manner of billionaire, including royalty—Prince William and King Felipe VI of Spain were in attendance—and sporting titans. Ariana Grande sat a few rows from Daniel Craig, who sat a few rows from Hugh Jackman.

The A-list quotient was such that, absent from the Royal Box, Brad Pitt—Brad Friggin’ Pitt—was exiled to sit in front of the press section. Which left bloggers, podcasters and deadline writers in the novel and unlikely positioning of maneuvering their gaze around the world’s most spectacularly coiffed head of hair to watch the action.

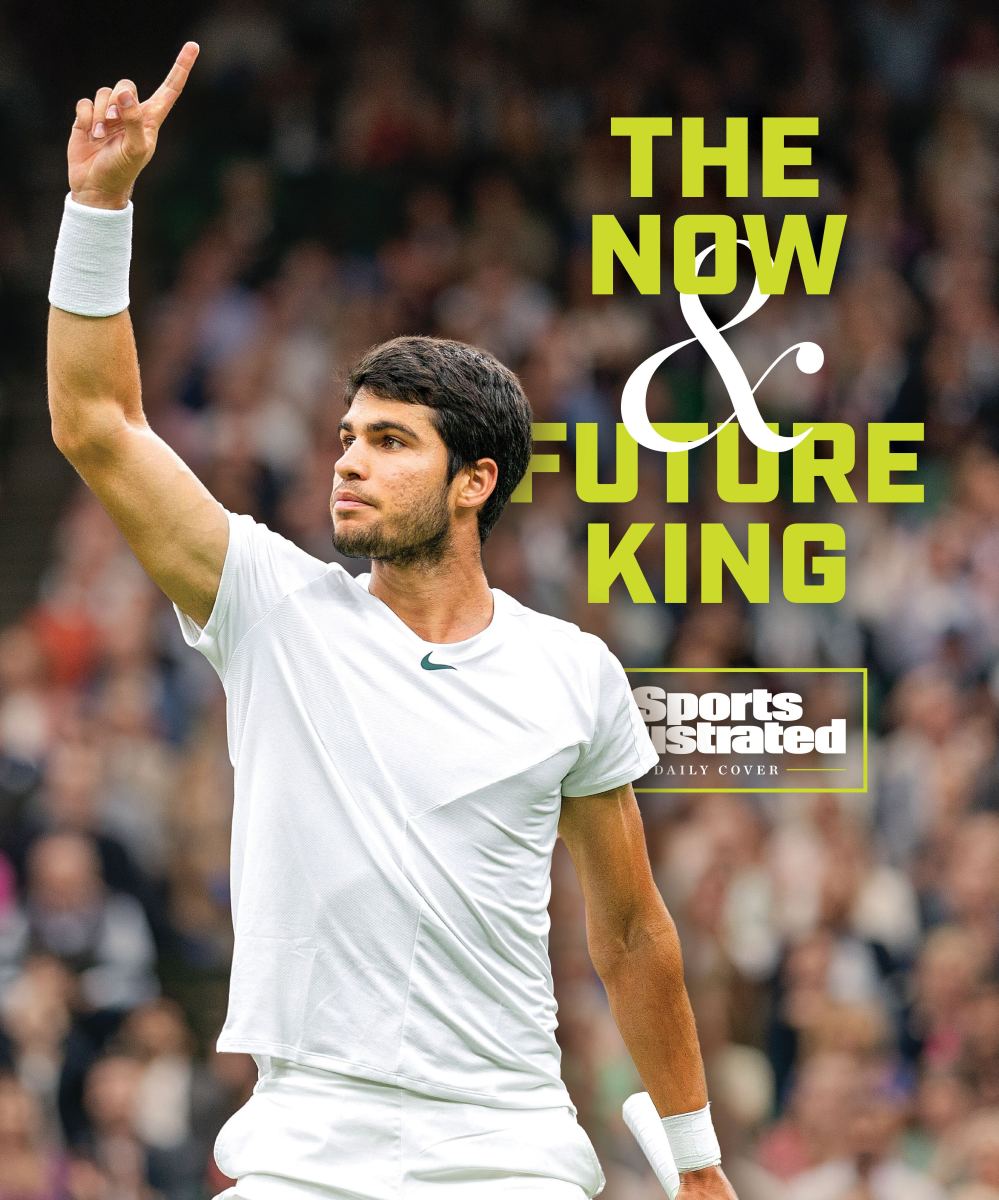

All these members of the landed gentry had come to see tennis royalty in the men’s final, a showdown pitting the sport’s reigning monarch, Serbia’s Novak Djokovic, against challenger-to-the-throne Spain’s Carlos Alcaraz. This was No. 1 versus No. 2. The sport’s present against its future. The wise and experienced and pragmatic 36-year-old confronting the live arm and limber legs and undented optimism of a 20-year-old.

And this was one of those rare global sporting events that would exceed its considerable hype. The match doubled as a five-hour refresher course on what it is we love so much about sports: unscripted theater, a battle equally mental and physical, swaying momentum, improbable twists, all garnished with a gripping conclusion. In the end, the challenger beat the (eight-time Wimbledon champion; 23 major-title holding) incumbent. To torture the king analogy further: This was both a coup and a coronation.

It wasn’t just that Alcaraz won a spell-binding, side-winding five-set match, 1–6, 7–6, 6–1, 3–6, 6–4. And it wasn’t just that he had won over the crowd, which, by the end, was arrayed, say, 80–20 for him (anecdotally, that ratio seemed to hold among the millions watching worldwide).

It was that Alcaraz had stared down the mighty Djokovic in a best-of-five match. And he didn’t blink. He overcame fatigue and nerves against perhaps the most mentally fit player the sport has ever known. Djokovic has made a career outwilling opponents, “taking their souls,” as he himself once put it. Not this time.

Alcaraz recovered from a dud of a first set to win the second and third. When Djokovic imposed his will on the match, he took the fourth set and, with it, the momentum. But then Alcaraz simply reset. Even after taking the lead three times in the fifth set, Alcaraz needed to hold his serve (and his nerve) against the ATP’s leading returner. No matter. He stepped to the line, literally, and came through. “It was,” as Alcaraz reflected to Sports Illustrated after the match in his steadily improving English, “epic … maybe something a one-in-a-lifetime.”

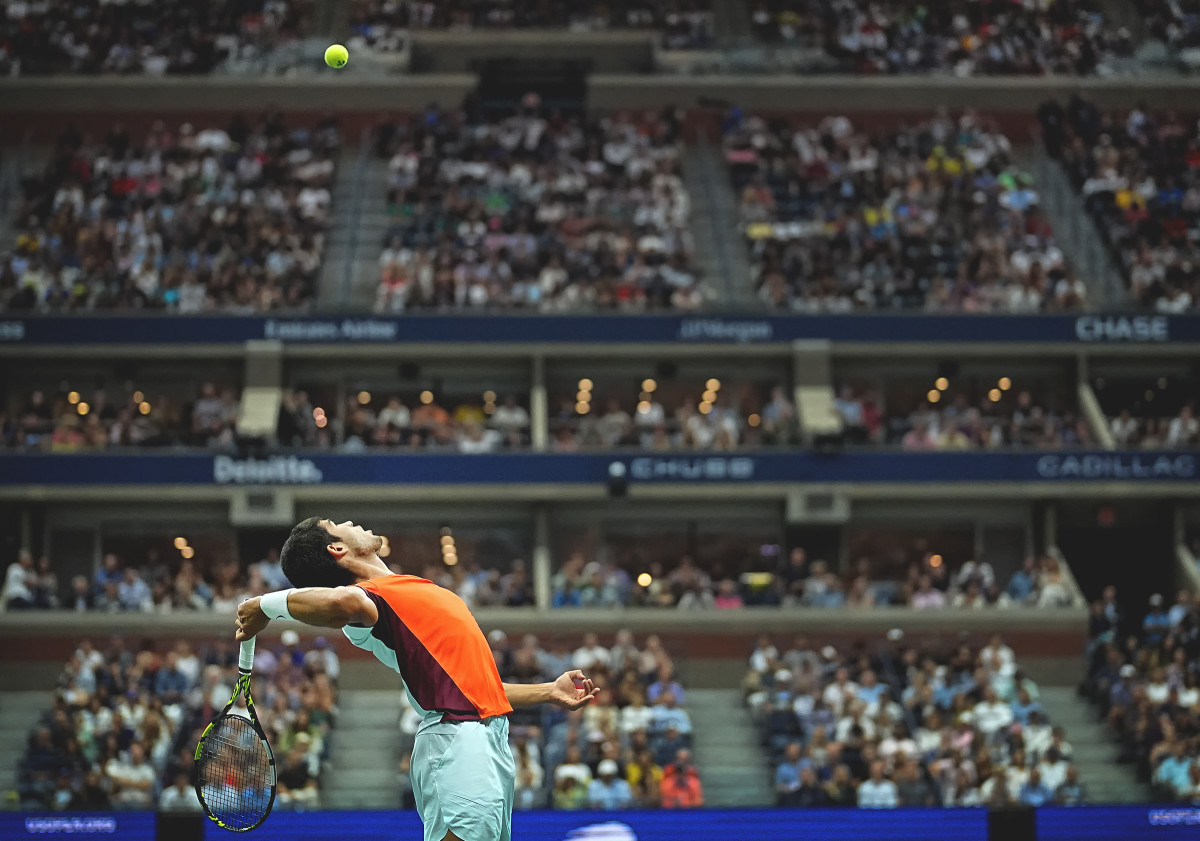

Which might also describe the player himself. For years, tennis has celebrated a gilded age of the Big Three—Roger Federer, Rafa Nadal and Djokovic, 65 majors among them—while wondering about the vacuum that awaits their retirement. Now Alcaraz has come thundering into the void, a fresh Wimbledon championship to go with the 2022 U.S. Open title he is preparing to defend—all while not just winning but also representing so many qualities the sporting public seeks in an athlete.

Forecasting tennis and picking winners is a fool’s errand. But, when the U.S. Open kicks off Monday in New York, here’s a safe bit of conjecture: Again and again over the next two weeks, you will hear the commentariat describe Alcaraz, the defending champion, as a melding of the Big Three, an amalgam of Federer’s fluidity, Nadal’s power and persistence, and Djokovic’s precision and unflappability. It’s an easy trope. It’s reductive. It’s also dead-on correct. And it’s fitting that tennis’s future draws on its past.

Tennis, you see, has never quite figured out its relationship with time. It is a sport so often seen as stubbornly retrograde, clinging to history, looking backward more than it does forward. There are still no decent tennis apps or video games. It is often averse to rule changes. Advanced stats are impossible for fans to find.

Other times, tennis is wildly cutting edge. It was among the first sports to use replay technology. This year, Wimbledon used AI bots for some of the highlights. Djokovic takes the court with a fitness tracker taped to his chest, providing him with a wealth of biodata he can consult later.

And now there is Alcaraz, who brings freshness and electricity and even novel shots. He wears the permasmile of a kid bemused by it all. He brings in new fans and is constantly in the “youngest-ever” records. Yet, at the same time, Alcaraz has these throwback qualities. He is a decidedly old soul, who casually—and without apparent irony, given his positioning—says things like, “Newer isn’t [always] better.”

Even the Alcaraz origin story is from a prior century. It does not involve high-tech training or global travel, but rather was—and for that matter, is—centered amid the orchards and olive groves of southeast Spain. If Madrid is New York and Barcelona is Los Angeles, Alcaraz’s home of Murcia is akin to, say, Little Rock, a solid, unflashy city of 400,000. It’s the kind of place that puts a water park on its civic homepage.

There, Alcaraz was raised by his parents, mother Virginia and father Carlos Sr., a tennis teacher. Padre had the good sense to realize early that his son had the essential makings of a Great One, prodigiously athletic but also inclined, constitutionally, to spend hours playing an individual sport. He also had the good sense—too rare among tennis parents—to know that teenagers often respond better to coaches who did not bring them into this world and have nothing to do with setting their allowance.

Fortunately for all parties, countryman Juan Carlos Ferrero had recently retired from a gilded pro career and had opened an eponymous academy in nearby Alicante. Ferrero once rose to No. 1 in the ATP rankings and won the 2003 French Open (ironically, within weeks of Alcaraz’s birth). Known for what he did, not what he said or wore, Ferrero cut the figure of a quiet leader, not easily impressed or rattled.

Still, he took one look at Alcaraz, “then maybe 13,” and saw it. Young Alcaraz layered muscular power with the lightest of touches, backing up a blistering serve with a drop shot he deployed as gracefully as though he were depositing an egg on the court.

“The word I would use: He was dynamic,” Ferrero recalls. “Like freedom, very free on the court. Maybe I didn’t think he was going to be the Rafa of the future. But, of course you think, ‘Oh, come on, that’s different. He plays good!’ Then, Ferrero spoke to the kid and was really sold. “He is a very natural guy, very humble guy. And we have the same culture, and that’s very important.”

Ferrero also recognized that the kid mastered the tennis balance of playing with passion but also controlled emotion. He won with grace. He was friendly with his opponents. Soon Alcaraz was coming regularly to Ferrero’s academy, which, built in its founder’s image, is the kind of unpretentious, sparse place where a boxer might train for a fight. Though Alcaraz’s talent was apparent and he already had an agent—he was 13 when he signed with Albert Molina, a Spaniard employed by IMG—he arrived with no ego.

Alcaraz turned pro in 2018 and quickly revealed he was as good as suspected. At age 18, he was winning ATP matches and doing so with such a complete game—an authoritative serve, slick movement, variety and touch.

Last year, in the week he turned 19, Alcaraz defeated Nadal and Djokovic in succession and then thrashed Sascha Zverev––another top player––in the final to win the prestigious Madrid Open. By the time the 2022 U.S. Open rolled around, he was among the favorites and validated that by winning the title, albeit without having to face Federer, Nadal nor Djokovic.

As it became abundantly clear Alcaraz was tennis’s Next Big Thing and heir to the Big Three, he resisted making any claim of tennis inheritance. For all the obvious parallels to Nadal in particular—in the way Alcaraz carries himself and quickly ladles praise on others, and would rather be fishing with his hombres than going to another black-tie dinner or fashion show—Alcaraz is reluctant to position himself as the Next Nadal or a Son of Rafa. “I am Carlos,” is a talking point he issues often.

This year started with a few mini setbacks. An injury to his right leg prevented Alcaraz from playing the Australian Open, amplifying concerns that he was doomed for a career that would trace the same path as Nadal’s. That is, a lot of brilliance, but also a lot of time on the IR and in rehab, the tax on such a physical style of play.

But Alcaraz recovered and won four of the first six tournaments he entered this spring, including the Indian Wells event, regarded as “tennis’s fifth major.” He defended his title in Madrid.

Then, seeded first at the French Open, he made it to a semifinal assignation with Djokovic. They split the first two rollicking sets. Early in the third set, though, Alcaraz was overcome by incapacitating, full body cramps. For a guy who practices for hours in the heat of Spain, he was accustomed to the conditions. No, he attributed the cramps to “the tension” of the occasion. With rare uncertainty in his voice he said, “I will try to not [let it] happen again in these matches.”

It didn’t. He promptly shifted to grass and won a title at London’s Queen’s Club. At Wimbledon this July, he recalled artificial intelligence, taking each bit of input and using it to get better and more precise. (Watching courtside, Andy Murray marveled, “You could almost see Alcaraz learning as the match was going on.”)

In the semifinals, Alcaraz all but gave a tennis lesson to recent No. 1 Daniil Medvedev of Russia, thrashing him 6–3, 6–3, 6–3. Then in the final against Djokovic, he recovered from that humiliating first set not by trying to outslug his opponent and throw haymakers, but by “playing my game and doing variety.”

Asked to recall the internal conversation he had with himself during the match’s critical moment, he paused, smiled and then answered as if revealing a tribal secret: “If I lose being aggressive, I don’t really lose.” How had he changed so dramatically from the player who succumbed to “tension” just five weeks earlier against the same opponent? “I learned a lot since then. I changed a lot since then.”

But outwardly he hasn’t. He passes his downtime like any other 20-year-old. He hangs out with his friends. He watches soccer. He plays video games. In part to improve his English, he watches American TV—he lists Suits among his favorite binges. Yet when Netflix sought him out to take part in its Drive to Survive tennis cognate, Break Point, the Alcaraz camp was cool to the idea. How is being trailed by cameras in service of his tennis? his team asks, not unreasonably.

In June, Alcaraz was announced as a new brand ambassador for Louis Vuitton, a win for the IMG machine. Yet even on his off days in Wimbledon Village, he was clad in shorts and a T-shirt, his head shrouded by a Nike bucket hat. Meanwhile, at the rustic Ferrero Academy outside Alicante, Alcaraz still keeps his same training quarters, an unprepossessing cabin that looks fit for a summer camper, not a young global superstar who, in 2023 alone, has been averaging $1 million a month in tennis prize money, and multiples more in endorsements and bonuses.

On Sunday in Cincinnati, Djokovic beat Alcaraz in a taut three-setter, earning a measure of revenge and ratcheting up anticipation for the two best players in the world to meet in a third straight major. If two players separated by 16 years can have a rivalry, this one is off and running. And running some more. Which is a blessing for the U.S. Open.

For the first time since the 1990s, the event doesn’t have Serena Williams, Federer and Nadal to promote. But it has Djokovic and it has Alcaraz, this kid with a tropism toward modesty coming to (Western) grips with the reality that he sits atop the sport. He arrives as the toast of tennis—literally—the face of the sport. Around New York, it is his giddily smiling, unshaven face that is splayed on billboards and buses. “Spectacular Awaits,” reads the accompanying text.

The kid is coming to deliver.