‘This Is for the Next Generation’: Inside the Fight, at Stanford and Beyond, to Save Olympic Sports

The Home of Champions at Stanford is not your normal Hall of Fame.

This 18,000-square-foot space on the university’s sprawling campus is a shrine to the country’s most successful college athletic program. The exhibit, opened in 2017, features more than 40 displays chronicling, in a state-of-the-art manner, the 130-year history of Stanford athletics. That includes a nation-leading 152 national championship teams, 270 Olympic medals won by Stanford athletes and the 25 consecutive Learfield IMG College Directors’ Cups, awarded annually to the country’s best athletic program.

Visitors can use an interactive interface to watch videos of 21 Stanford greats, see Jim Plunkett’s Heisman Trophy and, in one corner of this giant hall, view some of the most recent sports artifacts on display here, from Olympic fencer Alexander Massialas. Encased in glass before a life-sized photo of a fist-pumping Massialas are the fencing mask and foil he used to claim the silver medal at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games.

Three years after asking Massialas for those artifacts, the school eliminated the sport of men’s fencing.

“I haven’t thought about asking for the equipment back too much,” he says. “But when they still show that exhibit in their videos, I make sure to speak up on social media. They posted a video on the ‘Go Stanford’ Instagram on the history of athletics and its dedication to Olympic sports. It’s just a blatant disregard for their alumni.”

Massialas has become one of the most outspoken critics of the school’s decision to eliminate 11 athletic teams in a sweeping and stunning move last July. He’s one of the young leaders of a loud chorus of players, alumni and parents—they call themselves “36 Sports Strong”—who have embarked on a now-eight-month fight to persuade Stanford administrators to reverse, or at least reexamine, their decision.

For so long an exemplary athletic department, both in size and success, the Cardinal’s cuts were especially gripping. The university, after this season, will eliminate men’s and women’s fencing, field hockey, lightweight rowing, men’s rowing, co-ed and women’s sailing, squash, synchronized swimming, men’s volleyball and wrestling. The 11 sports represent roughly one-third of the school’s 36 sponsored athletic programs, account for 240 athletes and include programs that have produced 20 national titles and 27 Olympic medals.

The decision drives at the heart of an unsettling trend permeating across U.S. universities, where the survival of Olympic sports is in doubt. Sparked by pandemic-driven financial distress, 110 Division I sports teams have been discontinued in the 2020–21 cycle. But 24 of those were eventually reinstated, according to a site tracking the movement. For now, the 86 eliminated athletic teams are the most cut since 102 were slashed in 1997–98.

While Stanford’s decision aligns with a national trend, the 36 Sports Strong group’s efforts are part of a different movement: a sports-saving wave rolling across the U.S. The group’s primary goal—to have Stanford’s 34 nonrevenue teams self-fund—is a potential blueprint to a new collegiate model, they say, that could save the broad-based educational mission of so many colleges.

In a six-month-old fundraising effort, team leaders have raised pledges of $40 million to fund the 11 discontinued squads, and at least three of the teams have raised enough to self-endow, fully covering their operating expenses permanently.

Presented with this information, university leaders are steadfastly committed to their decision, showing no signs of restoring the teams. With communication stalled, some members of the group say they are left with no choice. Parents and alumni of the wrestling team plan to file a class-action lawsuit against the university.

“We don’t want to do the legal thing,” says Joe Ming, parent to a freshman wrestler and one of a dozen group leaders who spoke to Sports Illustrated. “We don’t want to take this to the streets, but they’ve forced us into it.”

Over the last several months, eight schools have reinstated at least one sports team that they had previously cut.

One school, William & Mary, reinstated seven. Two other schools, Brown and Dartmouth, reinstated five each. Some schools announced the reinstatements just weeks after announcing they were discontinued.

In almost every case, there existed one of two reasons a team was resurrected. Either a team raised enough funds to self-endow or self-fund for several years, or they threatened legal action on gender and race discrimination. Take, for example, Dartmouth. The school reinstated its five sports after accusations emerged that its decision unfairly impacted Asian athletes and women athletes.

In the case of the latter, leaders representing women athletes prepared to file a class-action lawsuit alleging the college was violating Title IX, a federal law that protects against sex discrimination by requiring schools to create equal opportunities and resources for women athletes.

“It’s all about power. Women only have it when they are ready to bring a lawsuit. And when they do, they can make enormous changes,” says Nancy Hogshead-Makar, a former Olympic gold medal swimmer and the founder of Champion Women, an advocacy group for girls and women in sports.

Hogshead-Makar’s group has played a role in nearly every women’s sports reinstatement this year, she says. When a women’s sports team is discontinued, Champion Women springs into action. It often meets with team leaders over Zoom, show them a school-specific presentation of Title IX data and organize the next steps, which many times is connecting them with an attorney.

One of those attorneys is Jeffrey Kessler, the co–executive chairman of the international law firm Winston & Strawn, whose representation helped Brown athletes have their sports restored over discrimination.

“It’s really shocking to see a school like Stanford cut these sports since that school is richer than Midas,” Kessler says. “You really wonder what’s behind this. I don’t see a financial basis for it at all.”

Stanford administrators do. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the school’s athletic department faced a mounting debt that it projected to be at least $12 million this year. The pandemic has exacerbated the issue and resulted in the cutbacks, which the school says will, eventually, save it $8 million annually.

Using the university’s own financial figures, 36 Sports Strong generated a study to show that the elimination of the 11 sports is only a minimal budgetary impact and attributes the department’s deficit to an 84% increase in salary and benefits over the last decade, much of it tied to football and men’s basketball.

On Tuesday, leaders of the group presented their financial findings to Stanford provost Persis Drell during a 35-minute Zoom call, where they also pitched a proposal: Reinstate the 11 sports and give them a five-year runway to self-endow, not just their own programs but also all 34 nonrevenue sports at Stanford.

“It was like we were talking to an empty suit,” says Kathy Levinson, a former three-sport athlete at Stanford in the 1970s who is leading the 36 Sports Strong movement and was part of Tuesday’s meeting. “I would say she was immovable.”

On the call, Levinson was joined by members of a separate but symbiotic movement, Keep Stanford Wrestling, as well as a prominent member of the higher education community: Kristina Johnson, president of Ohio State University and a former Stanford field hockey athlete. Johnson, the U.S. secretary of energy under Barack Obama, expressed the need for a broad-based educational system and encouraged Drell to grant permission for the programs to return as self-funded teams.

So many other schools have allowed their teams to return once self-funded. Why can’t Stanford?

Drell mostly toed the company line, Levinson says, emphasizing that the public financial figures did not reflect the department’s dire budget situation. The group pushed for more answers before Drell ended the call unexpectedly.

“It seems as if there was an answer other than finances,” Levinson says, “but she was not willing to give it to us.”

Many members of 36 Sports Strong theorize that the university, in part, eliminated sports to create admission flexibility. Stanford is one of the few colleges in the U.S. at capacity academically. In this theory, the university would now have the freedom to fill classroom spots occupied by athletes with those who may generate more tuition or carry a higher academic acumen.

Stanford’s athlete population was one of the highest in the nation at 12%, or one in every seven students.

“Maybe there was concern that 12% of the campus population was too much,” says Andy Schwarz, an antitrust economist based in California and a Stanford graduate himself. “The university admission process is trying to custom-craft a campus community.”

In a statement to SI, the school denied that admission flexibility was part of its decision to discontinue the 11 sports, pointing to the fact that Stanford grants about 70% of undergraduates some sort of financial aid.

Still, not everyone is satisfied.

“There is something wrong here,” says Annie Pilson, the mother of a field hockey player whose sports career may well be over now. “There is something that somebody is hiding.”

The 36 Sports Strong group is running out of options in its effort to keep the nation’s most successful athletic department together. The university is refusing its fundraising efforts, and it is not in a position to file suit over a Title IX violation, Levinson says.

However, at least some leaders of the school’s wrestling program are considering a different kind of legal attack. They are planning a class-action suit against athletic director Bernard Muir over, what they say, were deceitful and fraudulent claims he made to wrestling recruits, expressing a commitment to the program before pulling the plug.

“It’s a lack of integrity,” Levinson says. “The wrestling parents are aggressively pursuing that claim.”

Stanford’s cuts highlight a deeper issue that college administrators are wrestling with in these financially distressing times: Do you continue sponsoring sports that, for the most part, lose millions each year?

Eliminating them is tricky. Not only does it upend the careers of players and staff, but it further decimates a university’s original broad-based educational mission and adversely impacts the U.S. Olympic teams. While most countries produce Olympic teams through a government-operated training system, the U.S. mostly relies upon its array of colleges.

NCAA schools spend about $5.5 billion annually on Olympic sports. In fact, 88% of American summer Olympians in Rio had played their sport in college.

The concern is great enough that the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee created a Collegiate Advisory Council (CAC) to explore the issue. The council, on which Stanford AD Muir sits, recently created a think tank to further study the sustainability and advancement of Olympic sports.

“When you dig into this thing, you start to realize how much of America’s Olympic hopes are pinned on the collegiate model,” says Florida AD Scott Stricklin, who heads the 35-person think tank. “Our model is the envy of countries all over the world.”

But sustaining it is a financial problem.

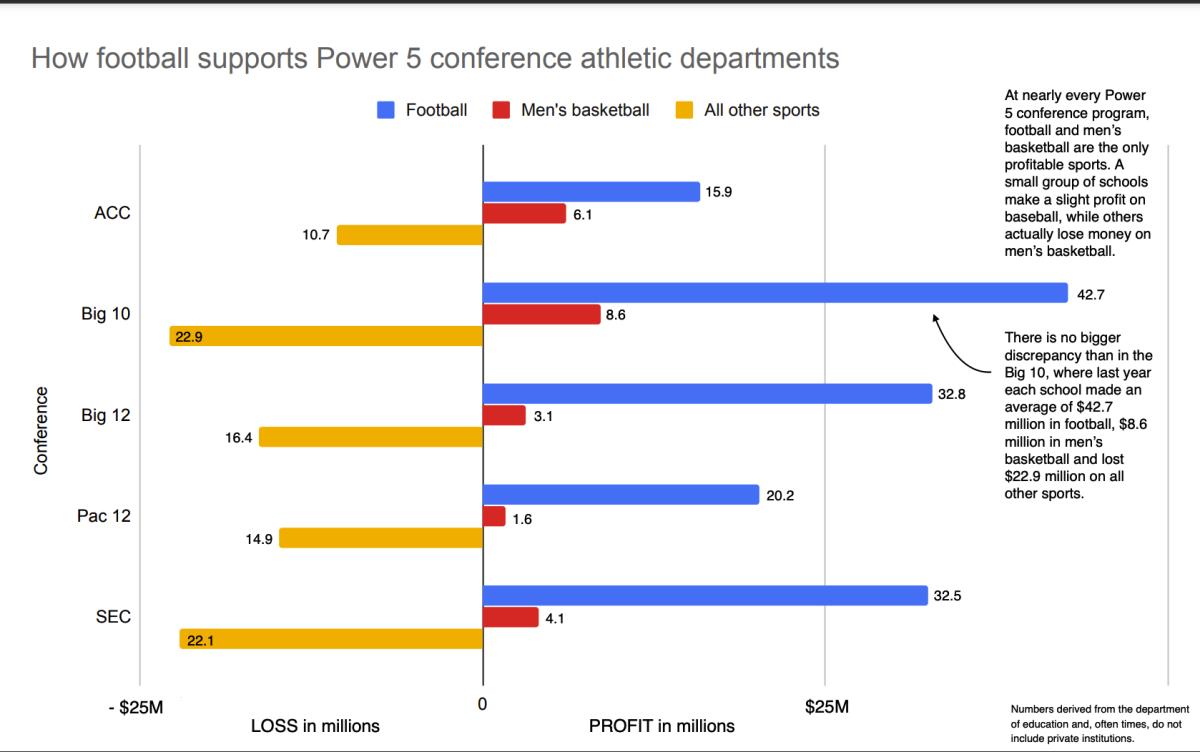

At most universities, two or fewer teams turn a profit: football and men’s basketball. Power 5 public universities made an average of $28.2 million in profit in 2019 on football, according to self-reported financial documents SI examined. Schools lost an average of $17 million on sports not named men’s basketball and football.

“Football allows us to have these other sports,” says Clemson AD Dan Radakovich, who recently discontinued his men’s cross-country and track programs.

At Stanford, many believe the university is choosing to pour more resources into the campus’s only real athletic moneymaker, football, at the expense of its broad-based educational mission. This is not only a Stanford problem. Football spending is skyrocketing nationwide, from the facilities arms race to coaching salaries.

College athletics has transformed into a big business and has forgotten its mission of supplying a wide range of athletic and educational experiences to young people, says Kathy DeBoer, the executive director of the American Volleyball Coaches Association. She is a member of the newly formed Intercollegiate Coach Association Coalition (ICAC), a group of 21 Olympic sports associations united under one umbrella with a mission to preserve college sports.

They believe discontinuing teams is a quick and fruitless fix to a much deeper problem—an NCAA model that, because of riches in football and men’s basketball, has lost its original purpose. Since 1990, NCAA Division I membership has grown by 58 schools, yet at least eight sports—all men’s teams—are sponsored by fewer schools today than they were 30 years ago, including wrestling (37 fewer teams), swimming (25), gymnastics (24) and tennis (22).

This year, more than twice as many tennis teams have been cut (21) as the next team, swimming and diving (10).

“One AD said to me yesterday, ‘We have two moneymaking sports to support 15 charities,’ ” says Tom McMillen, who presides over LEAD1, which represents the athletic directors of the Football Bowl Subdivision. “It’s a good way to describe it.”

Everyone doesn’t see it that way. Those against eliminating sports believe not every athletic team on campus must turn a profit.

“Does every academic organization make money?” asks Kevin White, the athletic director at Duke who chairs the CAC and a man who, in 38 years as an AD, has never cut a sport. “The 101 freshman composition class of 500 subsidizes the metaphysics class of 50. That seems to be O.K. It should be justifiable on the athletic side.”

Kessler, the attorney who represented the Brown athletes, quips, “Do we eliminate the drama department because it doesn’t turn a profit? No one goes in and says, ‘Let’s not keep Shakespeare!’ ”

Financially, administrators say things will only get worse with the NCAA planning to lift its amateurism policy and allow athletes to profit from their name, image and likeness. Endorsement companies that pour money into schools will instead split their investment between school and athlete.

“If I can find an AD that could tell me sports wouldn’t be cut because of these changes,” McMillen says, “I’d be very surprised.”

On May 15, 2020, Bowling Green eliminated its baseball program. On June 2, 2020, Bowling Green reinstated its baseball program.

A group of some 250 donors amassed a school-specific goal of $1.5 million for a sport that costs about $750,000 a year to operate. In reinstating the sport, Bowling Green announced plans to pursue a long-term fundraising solution with a select group of baseball alumni in order to sustain the sport in the future.

It’s a unique method to fully fund nonrevenue sports: Ask alumni to support them.

The 36 Sports Strong group at Stanford is following a similar formula in an effort to convince university leaders to resurrect the 11 discontinued programs. The $40 million in which it has pledged was gathered in a matter of months with a grassroots fundraising effort. The group believes it can reach the lofty goal of $200 million, a figure that the university itself believes would be needed to “permanently sustain these 11 sports at a nationally competitive varsity level,” a Stanford spokesperson said in a statement.

“Imagine what we could do with professional fundraising assistance,” says Adam Keefe, one of the movement’s leaders who played both volleyball and basketball at Stanford and has a son on the men’s basketball team.

The wrestling team alone has raised about $12 million, enough to fully endow the sport’s yearly operating expenses of $150,000, but that excludes scholarship costs. However, the team has mostly been restricted to 5.5 scholarships, roughly half of the NCAA maximum allowed, for a roster of 30 wrestlers.

“The real goal is to try to develop a blueprint to self-fund collegiate athletic teams,” says Ming, a leader of Stanford's wrestling parent group.

Self-supporting Olympic sports could be a game-changer in college athletics, experts say. For one, nonrevenue sports at the Power 5 level would no longer need to rely on the profits of football. Those at the Group of Five level and lower, where football makes little-to-no profit and Olympic sports are buoyed by student fees and institutional support, can save the taxpayer cash, says Schwarz, the economist.

In either case, a self-funding Olympic sport model leaves more money for the school, “in a perfect world,” Schwarz says, to spend more on the athletes.

“It just grows the surplus football and men’s basketball created,” he says, “and it gives the Olympic sports more clout. Being self-funding gives you some leverage. Football has that. It’s why it gets away with some of the crap it can get away with.”

While the scale of the fundraising effort at Stanford has turned heads, most administrators doubt that Olympic sports across all NCAA schools can fully fund themselves. Stanford, because of the economic base of its alumni, is different. This is a “rare circumstance,” says White.

So what’s the solution?

Many Olympic sports coaches think a cap on coaching salaries and staff sizes would alleviate the issue, and while that’s another far-fetched plan, it has legs now that Congress is involving itself in college athletics. Some lawmakers believe salary caps are necessary.

B. David Ridpath, an associate professor for sports management at Ohio University, believes that America should use an alternative model of amateur athletics found in Europe: Create club teams.

“Do we look at what other countries do?” asks McMillen. “If basketball and football can no longer pay for them, who’s going to fill in the holes?”

Already, Olympic teams are finding ways to save a buck here and there. In the future, they won’t be zipping across the country for events, instead busing to play teams within their geographic footprint, DeBoer says.

At Stanford, Pilson, the mother of Cardinal field hockey player Isabelle, questions the university’s fiscal responsibility. In fact she recalls two years ago when the field hockey team traveled to Australia to play a small handful of events. They spent 10 days in the country.

“Maybe don’t do that,” Pilson deadpans.

Isabelle, a junior midfielder, is in such a state of anger over the university’s decision that she recently told her mother she planned to never donate to Stanford as an alum. That sentiment has reverberated through those players and former players of the sports impacted—among others.

In fact, a star-studded group of Stanford alums signed a letter this past fall compelling the school to reverse course. The list included Andrew Luck, Kerri Walsh Jennings, Mike Mussina and Michelle Wie.

In the face of the backlash, Stanford officials have stuck to their plan.

“Every step we’ve made, we are shocked they have not reinstated,” says Jennifer Azzi, who led Stanford women’s hoops to the 1990 national title and won a gold medal at the 1996 Olympics. “We are being heard but ignored. We are told it’s time to heal. That’s the resounding message.”

But they’re not backing down. While the wrestling parents are poised to sue the school, Levinson says the 36 Sports Strong movement will now turn to the school’s board of trustees.

They’re hoping to get on the board’s April agenda in what may be the final step, a last-ditch effort to preserve the nation’s most successful athletic department.

“This fight is for the next generation of athletes,” says Massialas, whose fencing gear and photo resides in the Home of Champions. “We are doing this for the future of Stanford athletes.”