Julian Lewis Is Betting He’s the Next Big Thing

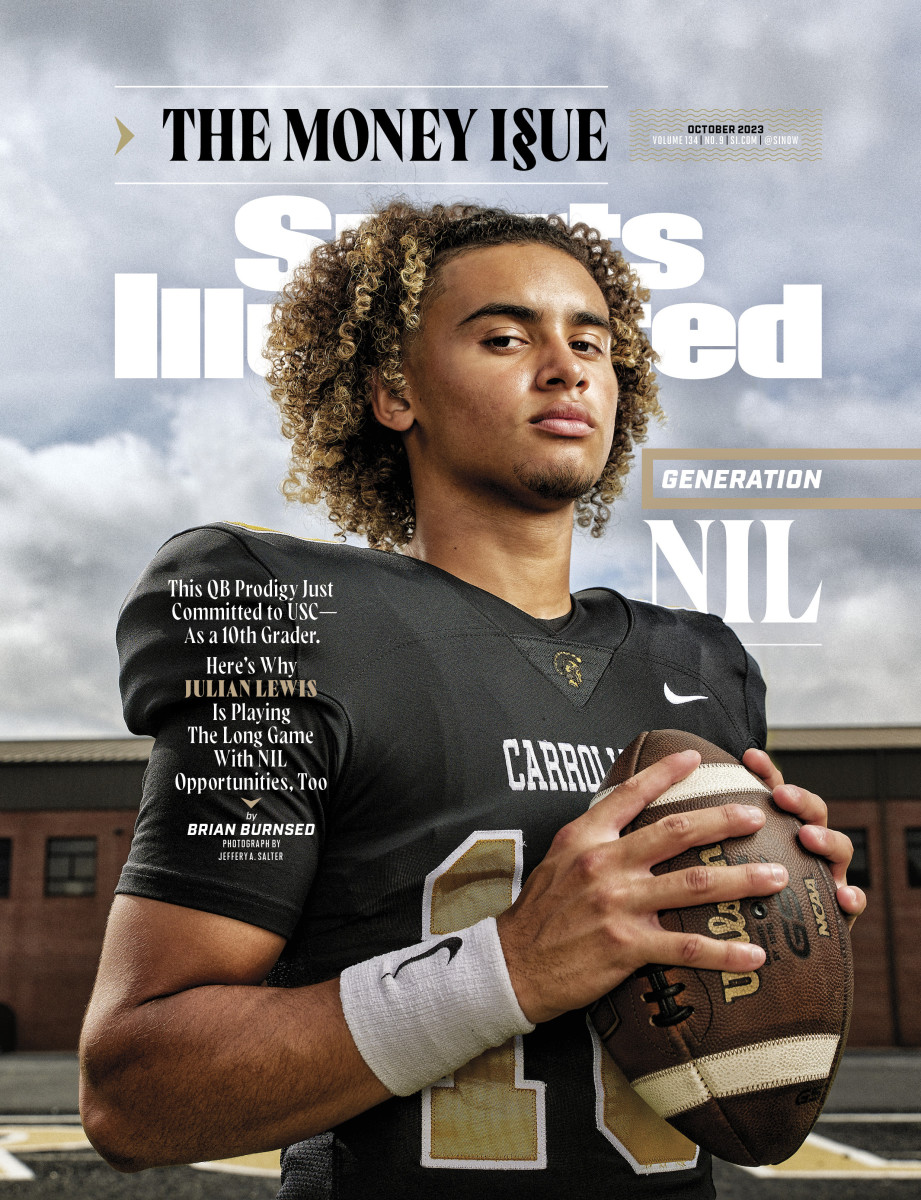

For once, the spotlight seemed faint. Save for a half dozen onlookers—some 126,000 fewer people than follow him on Instagram—the Carroll County Schools Performing Arts Center’s 1,100-seat auditorium sat empty as 15-year-old wunderkind quarterback Julian Lewis and a trio of his Carrollton High teammates, all clad in sport coats and slacks, fielded questions onstage from a Southern-drawled media contingent. Lewis’s brown-and-blond curls bounced, and his braces glinted as he met earnest questions about toughness and teamwork with platitudes about . . . toughness and teamwork.

The Aug. 1 regional media day event likely marked one of the final times in his young life that his words will be parsed not by a national audience, but instead by a smattering of radio listeners in this placid tract 50 miles west of Atlanta. In 17 days, Carrollton’s season opener would be broadcast on ESPN2. Four days after that, he would commit to USC. Just as he had been coveted by recruiters and coaches, he remains so by brands, desperate to associate with a teenager who could offer them hard-to-earn cachet. Julian’s anonymity was dwindling by the day.

Though he seemed to blend in with the players representing 10 local teams who were paraded onto the stage, he is, decidedly, not their peer. In 15 games last year he produced the most staggering freshman season in Georgia’s robust high school football history, amassing 4,118 yards passing and 48 touchdowns as he led Carrollton to the championship game in the state’s highest classification, 7A, which serves as a feeder system for the mighty SEC. He was crowned MaxPreps National Freshman of the Year and was the first sophomore in the Touchdown Club of Atlanta’s near-century-long history to be named to its preseason all-star team. But it’s a prize just out of the 6' 1", 190-pound QB’s grasp that truly separated him from the others onstage that summer evening: the endorsement deals he’s been offered—and turned down. According to Donald Woodard, an attorney advising the Lewis family, Julian has passed on more than seven figures’ worth of deals.

Now that the NCAA has lifted its prohibitions on athletes’ earning money from their name, image and likeness, the debate has found its way to high schools. Georgia remains one of the 19 states that don’t permit high schoolers to profit off their NIL. So, while other top high school stars can start stockpiling nest eggs, Julian—known best as “Ju Ju” by the masses—must bide his time.

His family could, of course, chase riches by moving to a more permissive state. But Julian’s father, T.C., enrolled his son in Carrollton’s school system two years ago specifically for the coaching and for Julian to be forged in one of the toughest high school football classifications in the nation. T.C. has essentially made a million-dollar wager that his son’s long-term prospects will be best served by focusing on his development as a player: As T.C. likes to say, “keeping the main thing the main thing.”

Rather than sit front and center in the auditorium that evening, T.C. watched from the atrium outside, wary of being a distraction, he says. “Did he do all right? I think he did all right,” T.C. would later simultaneously ask and affirm, well aware that Julian’s ability to maintain his poise during the external obligations demanded of transcendent quarterbacks will perhaps soon be just as vital as his ability to work through progressions as the pocket collapses. Onstage, Julian echoed his father’s mantra about football remaining his primary focus amid the hype: “Keep the main thing the main thing,” he assured local radio listeners—and, perhaps, himself.

For a 15-year-old would-be millionaire and the father who has invested so much in his development—carving a deliberate path, step by step—the main thing may soon grow much more difficult to define.

When Julian’s preschool teacher asked her students to put their toys away, Julian tended to hurl them into the appropriate cubby. Instead of admonishing his son when he learned of the behavioral quirk, T.C. set about finding ways to enhance his progeny’s hand-eye coordination. That preschool predisposition eventually morphed into nightly throwing sessions with a miniature football in a hallway at home: To end the drills, Julian had to make 30 throws with perfect form.

T.C., too, had been born into the sport. His father, Ty Lewis, was a high school football coach in New Jersey—today, a Thanksgiving game trophy is named in his honor—before dying from leukemia in 1990 at age 41, when T.C. was 14. T.C. went on to earn a scholarship at UConn to play offensive line, but he lost his passion for the game in Ty’s absence and left the team. So the family’s football legacy would eventually be passed on to Julian, T.C.’s only son of his five children.

By the time Julian was 7, he could whiz a youth-sized ball 25 yards, so T.C. created an Instagram account for his son, highlighting his exploits. Photos of a diminutive Julian, hair cropped, posing with trophies, soon peppered the page. “Started putting in work when I was 5 years old,” reads a September 2015 caption.

When Julian was 8, T.C. placed him under the tutelage of independent quarterbacks coach Ron Veal, who also trained the likes of Trevor Lawrence and Justin Fields. The duo often worked in a lonely field by an Austell, Ga., church, and Julian says he treasured the humid hours spent mastering his craft—rep after rep after rep—outside the view of smartphones. “I like getting better alone,” he says.

Julian’s parents had divorced, and when he was 10 his mother moved out of the state—and out of his life. T.C. retained custody of the four children. With the three older girls now out of the house, Julian and T.C. live with his new wife and their 6-year-old daughter.

It was also around that time that T.C. stepped away from coaching Julian, as the pair realized that T.C.’s demand for football perfection didn’t mesh with the pliability fatherhood often necessitates. Too often, Julian says, tensions from the field bled into their home, so the duo set boundaries that endure to this day. “I felt like he needed to start hearing other voices,” T.C. says.

T.C., who has a steady career in financial technology sales, spends thousands of dollars every year—including Veal’s services; entry fees for a slew of leagues, camps and tournaments; and the cost of traveling across the Southeast to compete and visit college campuses—not only on Julian’s development but also on developing awareness of his son in the right circles. The quarterback with perfect footwork and a propensity to fit the ball into tight windows turned heads at every stop. “He stood out because he was a third-grader and didn’t throw or hold himself or approach it like a third-grader,” says Richmond Flowers III, founder of the elite QB Collective camps. “He struck you as a prodigy.”

T.C.’s eyes well up when he considers how much he has poured into his son and what Julian’s talents portend. “I put blinders on and I drive forward,” he says, tears tumbling down his cheeks from under a black cap, pulled low. “There’s no shortcut.”

Two years ago, Joey King received a call from a number he didn’t recognize—today, he’s glad he answered it. King, who coached Lawrence at Cartersville (Ga.) High as he marched to two state titles, had just taken the Carrollton coaching job. At the time, T.C. was shopping around, hoping to find the right coach and right system to complement Julian’s skill set. Impressed by King’s scheme and how he’d maximized Lawrence’s talents, T.C. told him they were planning to move Julian to Carrollton for eighth grade, that it was worth the 45-minute drive every day from their home west of Atlanta. (Julian was eligible under a Georgia public school exception that permits some students to commute to nearby districts.) Julian had spent the previous year at Pace Academy, a well-regarded private school in Atlanta, but T.C. realized he had to prioritize football above all else. “If a kid is trying to go to Harvard, I need him enrolled in that kind of [school],” T.C. says, “but if he’s trying to go play at Alabama, Georgia, wherever, then let me put him in AP Football.” Julian has flourished in King’s honors-level classroom: By spring of 2022, the 14-year-old freshman had chased off upperclassmen quarterbacks on Carrollton’s roster—they transferred out—and earned the starting nod. “I knew immediately he was going to be special,” King says. “We’ve put a whole lot more on Julian than we did on Trevor.”

Julian brought more than just talent with him to Carrollton: In January 2022, having been enraptured by a documentary on Tua Tagovailoa’s development, Julian and T.C. reached out to Scotty McKnight, the film’s producer and a former standout receiver at Colorado. Early conversations on Instagram evolved into a plan for McKnight’s team to shadow Julian throughout his high school years. The project has since been sold to HBO and Warner Bros., and it will chronicle the entirety of Julian’s high school career. For now, Julian will not be compensated, though he and T.C. believe the benefit to his personal brand could be immense.

As he started to pile up gargantuan stats, leading previously unranked Carrollton to an undefeated regular season, some teachers at the school began to ask for autographs. College coaches laid siege—95 came to spring workouts this year—while McKnight’s camera crew loitered about.

In the state championship game, Mill Creek crushed Carrollton, 70–35. Despite the lopsided result, Julian threw for 531 yards, a state record, and five touchdowns against a defense laden with Division I talent. The performance had solidified him as one of the best high school players in the country, but he retreated to the sideline medical tent in the third quarter because he couldn’t keep his tears at bay. For all his efforts, he felt he had let his seniors down. While he tended not to mind the documentary crew’s presence, he did not want to sit in front of the camera the next day and relive the game. Still, dutifully, he understood interviews like those, as uncomfortable as they may be, are as essential to the job of being Julian Lewis, phenom quarterback as the touchdowns he tossed the night before. So he gamely answered questions despite the pit in his stomach, still wrestling with images of the sullen seniors—another lesson in

AP Football’s modern curriculum.

This July 4, Julian and T.C. agreed to a $5 bet during a Carrollton fireworks show: If fans approached and begged for a photo at least five times, Julian would have to pay up. Incredulous, Julian wagered on anonymity—or, perhaps, manners—carrying the day. Once the last boom had thundered overhead, Julian sent his father $5: He’d posed for 11 pictures. “You can tell when people are looking at you . . . but people try their best not to, like, harass me,” he says. “Of course, you feel the eyes.”

In a few years, likely sooner, Julian should be able to earn that $5 back pretty quickly. As soon as the Supreme Court struck down the NCAA’s NIL rules in 2021, college athletes began to monetize their brands, mostly via social media. NIL consultant Bill Carter says athletes’ accounts tend to boast triple the engagement of run-of-the mill online influencers because their digital brands are built on a foundation of real-world achievements that fans can follow. For corporate brands, a more engaged audience means a higher return on investment. “[Athletes] are really crushing social media influencers on that stage,” Carter says.

Until the Supreme Court decision, high school athletes had to avoid endorsement deals to maintain their college eligibility. With those consequences no longer in place, some state high school associations began amending their bylaws to permit athletes to cash in without losing eligibility. A new market was born.

While high school deals predominantly net athletes free gear or nominal sums, top stars like Julian stand to benefit from major national campaigns. Marketplaces like Icon Source have emerged to help connect brands with athletes. Its CEO, Chase Garrett, cites sports apparel companies like Under Armour that need a mechanism to easily target their next generation of buyers.

In December 2021, an 18-year-old Californian, Jaden Rashada, signed what is believed to be the first NIL deal for a high school football player, landing four figures to promote a recruiting app. Around the same time, T.C. began fielding offers from brands. Every month, more states began permitting high school athletes to ink NIL deals, but Georgia wasn’t among them. So T.C. enlisted Woodard, the sports and entertainment attorney, to help him navigate the unexpected new terrain along Julian’s meticulously hewn path.

Woodard was familiar with the nuances of NIL thanks to the years he’d spent on the USA Track & Field legal team and understood how to advise prodigious young talent, his firm having done the same for the likes of Atlanta-born rapper Lil Yachty. Far sooner than anticipated, T.C. was presented with a considerable return on his painstaking investment, but that would require leaving Georgia. Certain that the offers won’t disappear by the time Julian reaches college, father and son never seriously considered it, betting on Julian’s health and that Congress and the NCAA won’t regulate college NIL spending in the meantime.

Given the violence and uncertainty inherent to football, it’s a considerable risk. But Woodard has advised the Lewis family to focus on sharpening Julian’s skill set on the field while building a brand in parallel. Julian now manages all his own social accounts (aside from X, formerly Twitter, which T.C. runs). Thanks to some design help from friends, the posts are simultaneously polished and authentic: slick graphics touting his stats and the list of colleges he’d considered before USC, a bit of humor and videos of him rubbing shoulders with the likes of Fields. On top of his 126,000 Instagram followers, Julian has more than 36,000 on TikTok and more than 23,000 on X. “Our job is to try to keep his life as normal as possible and let him enjoy his process and get better,” Woodard says. “We know that everyone’s watching, and I know he knows that. But so far he’s done a good job of just remaining focused.”

Maintaining focus in the social media age is no simple task: Several fake accounts bearing Julian’s name emerged in recent months, spreading vicious rumors about his high school dating life. Some fake posts garner hundreds of thousands of views before they’re flagged and removed. “[Most people] have problems throughout the school,” Julian says, “but usually it doesn’t go to the whole country.”

Media psychologist Pamela Rutledge says the sort of social media attention that accompanies fame and NIL money can be tremendously rewarding, both socially and financially, but also potentially treacherous. She recommends young athletes and influencers like Julian proactively avoid deriving too much self-worth from their online brand (easier said than done). Plus, she says, the scrutiny of hundreds of thousands of anonymous digital eyeballs can make it difficult to learn from mistakes when any small misstep is met by public shame instead of a private lesson. (T.C. has told Julian that if he ever gets a speeding ticket, the incident may wind up on SportsCenter.) Having watched Lawrence grow up in the social media age, King understands well the perils that await Julian: “There’s leeches everywhere,” he says.

Earlier this year, Woodard drove nearly two hours south of his Atlanta home to attend a Georgia High School Association board meeting, pulling aside executive director Robin Hines to explain how NIL could benefit athletes and families in the state—and, perhaps, make sure that future Julians don’t leave it altogether. Hines has since been lobbying state educators and legislators to make Georgia’s rules more permissive.

The group’s executive committee will weigh whether to amend the relevant bylaws in October. They are widely expected to do so. In that case, T.C. and

Woodard say they will scrutinize each offer rather than grab every available dollar, steadfast in ensuring that Julian’s talents on the field aren’t eroded by the burgeoning opportunities—and demands—off it. “If he can set himself up, his life is different before he [leaves] high school,” Woodard says. “The pressures of finances and what he might want to do are eliminated—so long as you put some of that money away.”

Between summer two-a-day practices, Julian retreats to his beige-carpeted room in the rear corner of a modest new craftsman home with a football-shaped doormat. Despite the pigskin kitsch, Julian insists that he and his father don’t spend hours talking shop between practices. For Julian, aside from watching film, football doesn’t exist under that roof: It’s his refuge from the unpaid job of being Ju Ju Lewis, the phenom, the brand, the superstar. Instead, inside those quiet confines, he can be Julian, a 15-year-old kid who adores his girlfriend and video games.

The family relocated there in June to be closer to Carrollton High, so his room’s walls remain largely unadorned. In the corner rests a well-worn gaming chair and a TV, flanked by an Xbox and a PS5. (He boasts that he’ll have a PC for gaming soon, too.) He likes to play Fortnite and Madden online with other top recruits around the country he’s met at camps, their friendships forged over a shared understanding of the spotlight’s blessings and burdens.

Julian doesn’t exude cockiness, only quiet confidence that the goals he has long worked toward—the only ones he has permitted himself to envision—are nearly upon him, no matter Georgia’s decision on NIL. “I don’t want to be steered off of what my path is or what my goal is. I want to be an NFL player. I want to be the best player of all time. I’m not focusing on money right now because in the future I know, perfectly, my kids and my kids’ kids are going to be solid on everything. I’ve come too far and have done too much to worry about that right now,” he said a few days before his braces were scheduled to be removed. “I’m gonna have it one day.”

He waited until after football season to apply for his learner’s permit. And he’ll do the same before he earns his driver’s license this winter. Once more records are broken and wins are accumulated, he’ll take a driving test. Just as seemingly everyone else in his orbit does, a DMV worker will study his every move. Knowing that moment is fast approaching, Julian stayed up until 2 a.m. one night this summer, scrolling through pictures of a matte-gray Mercedes-Benz AMG C63 and salivating over its black rims, red brake calipers and foreboding grille. Fully loaded, it costs more than $100,000.

If he lived in California or Louisiana or Tennessee, that Mercedes might already be sitting out front on the home’s bleach-white concrete driveway. Yet, he lives in Georgia and understands that mountains of work await—for now, as ever, football must remain the main thing. Even so, some nights, the nation’s top quarterback prospect can’t pull his gaze away from that sports car, sifting through photos of his future and wondering just how soon it might arrive.