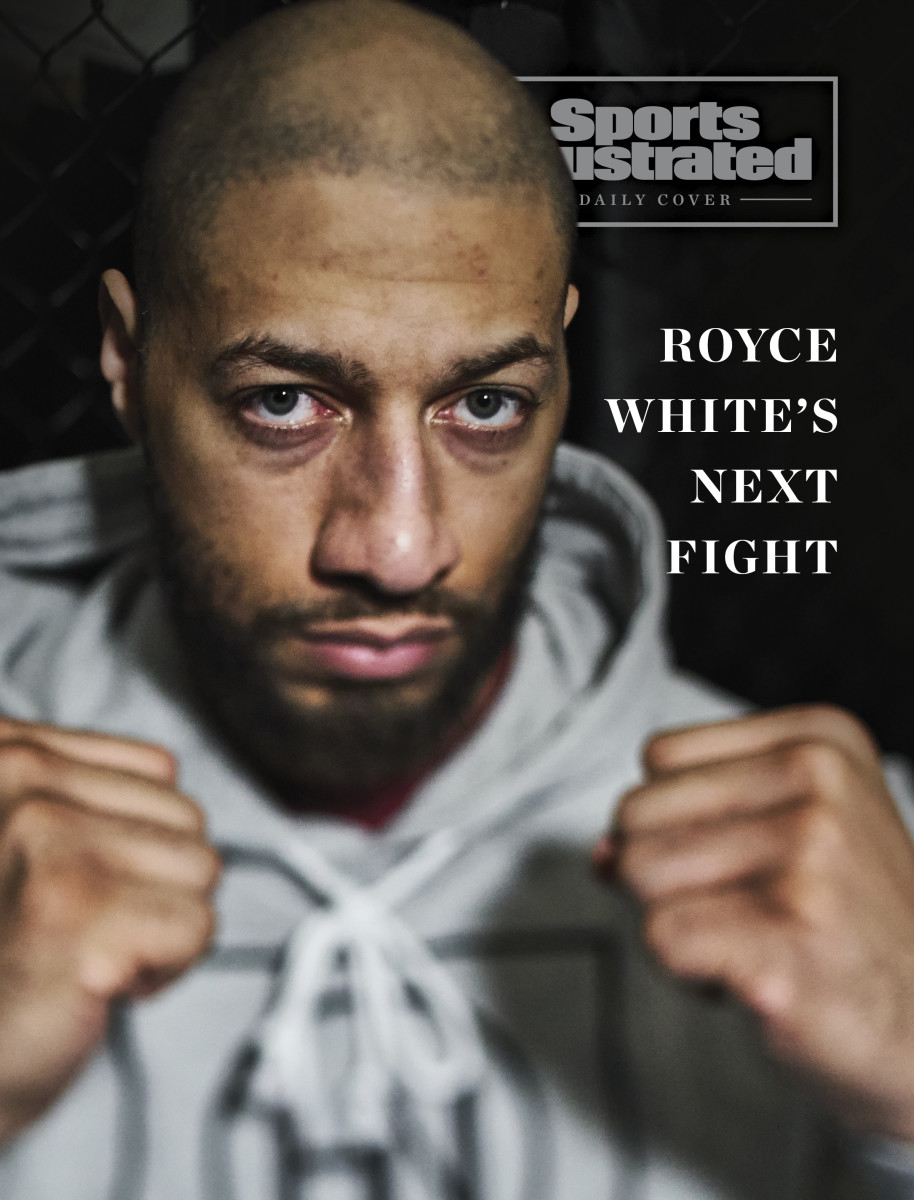

Royce White Takes on MMA

The No. 16 pick in the 2012 NBA draft is basted in sweat, huffing and puffing in the gym as the veins on his arms and neck look as if they’re attempting a jailbreak from his skin. At 6' 8" and 260-or-so pounds, Royce White is a mountain of man, but surprisingly agile. He’s going through a battery of meticulously designed drills, alternately meant to improve offense, defense, movement, footwork and stamina.

Yet in this gym, there is no hoop. And there are no balls. Actually, check that. There are balls. They just don’t bounce. Plyometric and medicine balls. White is working to improve the range and accuracy not of his jump shot, but of his punches. The defense isn’t about preventing his man from scoring; it’s about preventing his opponent from blasting him in the face. The idea is not to conserve energy for the final, critical minutes of the game, but rather the final minutes of a fight, when your back isn’t just metaphorically against a wall, but literally pressed up against a chain-link metal fence.

It was one Minnesotan, F. Scott Fitzgerald, who declared that there are no second acts in American life. It’s long been disproven—even A-Rod is beloved these days—and here now comes another Minnesotan, Royce White, age 28, attempting a most unlikely sports encore. Six years after leaving the NBA—blackballed, he insists—he is refashioning himself as a mixed martial arts fighter. He began training in 2018, preparing for his first fight, likely to come later this year.

What’s the motivation? White knows the question is coming and, like any good fighter, has a counter. As is often the case with White, it comes from an unlikely angle. “As a basketball player, I watched the deterioration of the competitive ethos, the erosion of the value of competition. The entertainment and the dollars [subsumed] competition on so many levels,” he says. “Mixed martial arts, it’s not ‘just business.’ It’s entertaining but not entertainment. It’s the highest level of competition. And the purest.”

***

Growing up in the Twin Cities, White was an extravagantly gifted athlete. Just as he could play any of the five positions—and take justified pride in resisting classification—his interests extended well beyond basketball. He was “a reader, a thinker, a seeker,” comfortable using his mind to engage. He was the kid who stayed after class to debate teachers.

At 16, when White went through a school-based mental health program—“one that federal government has since disbanded, I should add,” he says with annoyance—he was evaluated by a family practitioner. The doctor diagnosed him with generalized anxiety disorder. He read the definition in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders and recognized himself. He also recognized the symptoms in his mother and grandmother. It was, as much anything, a relief. So you mean to tell me, he recalls thinking, I’m not the only person on the planet who feels like they’re going to die every four hours?

The state’s Mr. Basketball in 2009, White committed to the University of Minnesota, but he never played a game. As a freshman he was suspended after being charged with theft and fifth-degree assault for allegedly shoplifting and shoving a security guard at the Mall of America. (He ended up pleading guilty to a lesser charge.) He transferred to Iowa State, where, wrapped in the warm blanket of a college community, he was open about his mental health challenges. On campus, he became something of a cult hero. He recalls: “It was like, ‘Royce White has what I have—what my sibling has or my boyfriend or girlfriend has—and he’s doing great on the basketball team.’ ”

Meanwhile, the Cyclones’ coach at the time, Fred Hoiberg, went to great lengths to accommodate White. A particular manifestation of his anxiety was a fear of flying. When possible, the team permitted him to travel by car. One of the better college players in the country, White averaged 13.4 points and 9.3 rebounds in 2011–12, his first season in Ames. With Hoiberg, a 10-year NBA veteran, openly touting his star as a lottery pick, White declared for the NBA draft.

Before draft night, White quickly got a sense that college and pro basketball held different attitudes about mental health. In a series of predraft interviews, multiple teams warned White that he would have to confront his fear of flying and he shouldn’t expect special treatment. A Sports Illustrated story from the time with the headline the mystery pick is royce white asked in its subhed: “[A] top prospect’s mental disorder raises the question, how much risk are teams willing to accept?” White grew disgusted when he read media reports predicting the answer would be not much.

“I was like, ‘Are you kidding me?’ ” he recalls. “Then I realized the media was right.”

For draft night, White agreed to be featured in a video documentary for the website Grantland. In one scene as he prepares to address an Iowa State practice gym filled with children who have come to meet him, he stops short of entering. “I can’t go in there, I can’t do it,” White says, as he paces in a weight room, looking at the camera. “I can’t show my face right now. There’s love in that room, but the way my brain feels, that’s fear. I’m working myself to get in there though.” It finally passes, and he meets the kids.

White ended up going to the Houston Rockets, midway through the first round, ahead of players like Draymond Green, Jae Crowder and Mike Scott, who are still going strong in the league.

White says that when he arrived in Houston, the team was initially accommodating and engaged him in discussions about how to handle his anxiety. Then the tenor changed. The NBA sent word that if the Rockets provided private transportation for White, it might violate the league’s salary cap.

White being White, he confronted this with a combination of logic, outspokenness and media savvy. He asked why player mental health issues were handled so differently from physical issues. Why the National Basketball Players Association, so willing to devote time and resources to negotiating matters like a pregame dress code, was “silent” (his word) about crafting mental health policy. Again and again he made a larger point: Mental illness in America is an epidemic, and the NBA isn’t paying proper attention to it.

After the draft but before the season, White demanded he be able to travel by bus. If the team wouldn’t pay for it, he’d put down the money himself. Later, he asked the Rockets to hire a physician to monitor his mental health daily and determine whether he could be cleared to play. A five-page letter that Rockets general manager Daryl Morey wrote to White leaked to the public. It read in part: “We have bent over backwards to accommodate your requests and help you meet these goals. . . . The bottom line is that we remain willing to work with you on issues that arise from legitimate medical need, but you have to come to games, practice and everything else that you are able to do, just like any other player.”

That November, White declined to attend the Rockets’ games and soon after refused a reassignment to their G League team, the Rio Grande Valley Vipers, prompting Houston to suspend him without pay. (The ban was dropped when White agreed at the end of January to report to the Vipers.) In the dispute—and the discussion of mental health, made uncommonly public—neither side budged much. White never played for the Rockets—though he averaged 11.4 points and 5.7 rebounds in 16 G League contests—and was traded after one season. (The Rockets did not respond to SI’s requests for comment and the NBPA declined to comment on the record.)

It’s up for debate whether White’s anxiety, and candor, exacted a price on his career. Or whether institutional resistance prevented him from fulfilling all that potential. But here, indisputably, is the sum total of his NBA tenure: three games, on a 10-day contract, with the Sacramento Kings, and no points scored. On March 28, 2014, he wasn’t re-signed. After that, he played in Canada, Europe and, most recently, the BIG3.

As White drifted further and further from the NBA, something remarkable happened. Player after player came forward speaking openly and without embarrassment about their mental illnesses—most notably, All-Stars Demar DeRozan

and Kevin Love, but also Kelly Oubre Jr. and Ben Gordon, among others. Each was met with sympathy and empathy.

NBA commissioner Adam Silver went so far as to state flatly, “A lot of [NBA] players are unhappy.” While Silver attributed it largely to social media, he added, “We are living in a time of anxiety.” Before this season, each team was sent a memo from NBA headquarters outlining the leaguewide mental health guidelines. Bullet points included:

• Making mental health professionals with experience in assessing and treating clinical mental health issues available

to players.

• Identifying a licensed psychiatrist to be available to

assist in managing player mental health issues.

• Enacting a written action plan for mental health emergencies.

White’s role in starting the conversation has not gone unnoticed. Says one former NBA general manager who considered drafting him in 2012: “I’m still not sure how good he was as a basketball player. But if we’re talking moving the needle in terms of getting comfortable talking about anxiety and mental health, he’s a Curt Flood–type figure.” After opening up about his anxiety and depression, Love tweeted at White in August 2018, “Couldn’t have been done without you setting this thing in motion.”

***

BY THEN, White had switched his sports loyalties. He says that as a kid he was captivated by MMA, but “cultural forces” prevented him from taking it seriously. “The guys I came up with—black males—we had to be careful with our image. Being a mixed martial artist would have sounded strange,” he says. “And sometimes strange gets grouped with trouble.”

But now MMA was calling—and White was in the right place. There’s long been a thriving MMA scene in the Twin Cities, with

lots of fighters—often grain-fed Midwestern wrestlers who transition to striking—and an esteemed coach, Greg Nelson, who presides over the Minnesota Martial Arts Academy, a 12,000-foot gulag in suburban Brooklyn Center. Dozens of UFC fighters have passed through, most notably Brock Lesnar, the former University of Minnesota heavyweight wrestler and WWE star who did a turn in the UFC, briefly winning the heavyweight belt. (When Lesnar returned to pro wrestling, he donated to Nelson’s gym the replica UFC octagon he used for training.)

As a fighter, White was—and is—a study in extremes. With virtually no prior training, he’s had to learn an entirely new set of skills, most notably Brazilian jiujitsu—rolling, it’s called—as much a mental and tactical challenge as a physical one. White has also had to adjust his cardio and deal with a new proportion of stress hormones in competition, since the adrenaline-cortisol cocktail you get from nailing a jump shot isn’t the same strength as the one that comes when you nail another man with a roundhouse kick to the head.

White has held his own sparring at the gym with Pat Barry, once a UFC heavyweight contender and a pro kickboxer. But Barry is 5' 11" and 40 years old. White looks comfortable fighting on the outside, not surprising given his seven-foot wingspan. But his takedown defense remains raw.

White is an elite athlete, though, and one who swears, because he did not put on much NBA mileage, that he has the body of a man three or four years younger than his actual age. “It’s not just that level,” says Nelson. “It’s the work ethic that goes with it. When you’ve been a professional athlete, you know what it means to train. And Royce is putting in the work.”

Many who don’t quite understand the concept have asked White: Anxiety disorder cut short your NBA career, so how is the prospect of getting smashed in the face not more anxiety-inducing? He has a response at the ready: “Anxiety doesn’t work in a linear, boxed-in fashion. Some people are anxious with spiders. Some people are anxious in dark rooms. Some people don’t like being around other people. Some people need to be around other people. It’s pretty individual.”

In other words, White feels confident that his anxiety will not take a toll on his fighting or the pressure that comes from competing in a combat sport. While he still prefers not to fly, he’ll get on a plane if he has to. And above all, in this, the ultimate individual sport, he’ll handle it himself, without coaches, executives and teammates making judgments about him and decisions for him.

As a fighter, White draws inevitable comparisons to Lesnar: both from Minnesota, both heavyweights, both converts from another sport. But Lesnar, a former NCAA All-America wrestler, entered the UFC with a combat-sports background. The more instructive comp might be Greg Hardy: the former NFL star who was banished from the league for domestic violence and took up MMA. He’s fought five times in the UFC and done well. (There are less successful converts, too. Johnnie Morton turned to MMA after he retired as an NFL wide receiver. In his first and only pro fight, he was not only carried out of the arena on a stretcher after a first-round KO, but he also tested positive for elevated testosterone levels.)

White could have made his MMA debut by now, but he’s been holding out for a big-time opponent in a big-time venue with a big-time outfit, ideally the UFC. Most likely, though, he’ll take his first fight later this year with a regional promotion.

Dana White, the UFC chieftain, is aware of the former NBA player and is intrigued, but adds that he hasn’t scouted White.

“We’ll see what happens when he takes a big shot,” says Nelson. “That’s when you learn a lot about someone and you learn a lot about yourself.”

Characteristically, White has given plenty of thought to his career change. So much that he’s written an e-book about it, MMA x NBA: A Critique of Modern Sport in America, which is available on Amazon.

As he sees it, he’s already 1–0. “You know, I had everything to gain by not even saying anything about mental health,” he says. “Actually, I was advised by my agent and by other people in the basketball world to not go public and talk about mental health at all. Because I was in line to make a couple hundred million dollars. But I said, ‘Hey, mental health is a conversation we need to [have].’ And I am living proof that people with anxiety not only aren’t weak, but they can be profoundly strong.”