A Quarterback and His Game Plan, Part II: Virtual Reality Meets Reality

In Part I of this story, The MMQB explained how the game plan, the weekly and oft-times encyclopedic secret document each team uses to strategize against the upcoming foe, was absorbed by quarterback Carson Palmer of the NFC West-leading Cardinals in the days leading up to Arizona’s Week 8 game at Cleveland. Palmer admitted to “freaking out” when he first got the game plan on Tuesday, but by Saturday night he was comfortable with what he and his team had in store for the Browns. Today we explain how the game plan worked that week, and how sometimes there’s just no accounting for little things—the wind coming off Lake Erie, or a great player’s balky hamstring—that can affect it.

CLEVELAND — On a sunny and windy afternoon on the shores of Lake Erie, Arizona coach Bruce Arians covered his lips with the laminated rectangular play sheet in his left hand. “Seventeen,” Arians said into his headset microphone. “Flip 17.” That single number—signifying Arians’ call for the Cardinals’ 22nd play of this game against the Browns—blared into the tiny speaker in the helmet of his quarterback, Carson Palmer, standing 45 yards away on the field at FirstEnergy Stadium, early in the second quarter. The Cardinals trailed the Browns 14–7.

Palmer looked on his wristband, which listed all 171 plays in that day’s game plan, coded 1 through 171 in 10-point-type, and found the one Arians wanted. (The number coding minimizes miscommunication between the sideline and the quarterback in loud stadiums.) Play number 17 read: Pstl Str Rt Stk Act 6 Y Crs Dvd.

Palmer leaned into the Arizona huddle and called, “Pistol, Strong left … Stack Act 6, Y Cross Divide.”

About Arians’ “flip” call: During the week this play was designed as “Strong Right,” to be run with the ball on the right hash mark. But now, from the Arizona 36-yard line, the ball was spotted on the left hash. Arians reminded Palmer to flip the play, putting the tight end to the left of the formation (strong) and the two wideouts opposite the tight end, to the right. Arians trusted his 35-year-old quarterback to get it right, and Palmer did.

Bruce Arians loved this play. Carson Palmer was positive it would get one of his two receivers, Larry Fitzgerald or rookie J.J. Nelson, in single-coverage downfield in a matchup they could win. This, coach and quarterback believed, was the home run—six such downfield bombs were in the game plan, under HOME RUN, Arians’ favorite play category—that could turn the game around.

Football games are very much like what happened next. Imperfect. Unexpected things happen on almost every play. Players miss assignments. Coaches put players in bad spots. Players trip. Balls bounce funny. The Cardinals spend millions on scouting and coaching and technology and, this year for the first time, virtual reality, to learn, to practice and predict what foes will do in this spy-versus-spy grid game. Sometimes in that game, you see an opportunity. That’s what the Cardinals saw here, and on a glorious fall day in northeast Ohio, Palmer was determined to take advantage of it.

As the play unfolded, seeing his team’s error, a Browns employee in a hooded sweatshirt on the Cleveland sideline put his hands on either side of his head, with the expression, Nooooooooooo, on his face.

Been to Cleveland? Been to a football game on the lake? Wind matters. Soon after the Cardinals’ flight landed on Friday night, Palmer and a small party had a late dinner downtown with Dave Zastudil, former punter for Cleveland and Arizona. “Punters are my best friends,” Palmer said. “They know the wind in every stadium. And Dave played in Cleveland. I grilled him.” Though Palmer used to play in the same division as the Browns—he threw six touchdown passes for the Bengals in this stadium in 2007—it had been five years since he set foot in the place, and he wanted a refresher course.

“What you don’t want,” Zastudil told Palmer, “are the south or southwest winds. The wind comes in the open end of the stadium and just swirls. It can feel like the wind’s at your back, and then in a different part of the field, same direction, it might feel like the wind’s in your face.”

When Palmer awoke in Room 624 of the Cleveland Intercontinental Hotel on Sunday morning, he checked the Weather Channel app on his phone. South to southwest winds, read the forecast for Cleveland. Gusts to 25 mph.

You’re not in Glendale anymore.

On the field before the game, local meteorologist Jason Nicholas noted the American flag blowing hard in the gap between the south and southwest stands. “Palmer was dealing with a downwind, a headwind and a tailwind in addition to a little bit of a cross wind,” Nicholas said. “That can happen because the way the stadium is made—if we get a wind out of that southwest direction, it can do whatever it wants when it gets inside.”

Palmer couldn’t quite figure out how to account for the wind, and on a day with some deep shots in the game plan, that would be important. “It was whipping down our sideline and hitting you in the left ear,” he said. “And as it came down, it wrapped around the stadium. The higher up you go, it’s just like a tornado up there. You throw it, and it’s just a guess.”

The Cardinals had been running the ball well, and Arians said during the week he was most excited about the run game against the Browns. Still, of the 171 plays in the game plan, about 95 were passes, so clearly Arians intended to call his share of those, wind or no wind. On Saturday night Arians, in conjunction with Palmer, had finalized the first 30 plays. Fifteen runs (Arians picks), 15 passes (Palmer picks). Yes, the coach allows his quarterback to pick the first 15 throws of the game. “I never want to call a pass a quarterback is not comfortable with,” Arians said. “Tell me what you like, and we’ll run ’em.” There’s a bit of insurance there, because for a play to be in the pool to begin with, Arians and the offensive staff had to like the play enough to include it.

The Browns won the opening coin toss, chose to defer and take the wind. Arians picked a run on his first play, a unique one. A Jet Sweep, with the speedy Nelson. On Toy Z Q 29 Sweep, Nelson streaked from split right in motion behind the formation, took the handoff from Palmer … and got smothered. Poor execution by Nelson, who should have stuck his left foot in the ground and burst upfield a couple of steps before the smothering.

“That was okay,” Arians would say later. “Sometimes you run a play to set up something later. We had a trick play in the game plan for later. This set it up.”

Translation: Arizona had another play sending J.J. Nelson in motion with something weird coming off it. Arians wanted Cleveland to see Nelson do the Jet Sweep when he went in motion, so that the next time it was called and the play began, the Browns would figure the same thing was coming. (Spoiler alert: The next time never came. Play saved for another day.) That’s a big part of game-planning. “The idea is set teams up when you can,” said Arians. “Like, when they’re watching us on tape, I don’t want them to be able to figure us out. When teams prepare to face us, they’re not practicing what we’re going to do. They’re practicing what we have done.”

That helped the Cardinals on the sixth snap of the game, Trips Sailor Right, another play involving the rookie Nelson. Coming in, Nelson had been on the field for just three plays in the previous five games, so the Browns had to be asking: What is he—a changeup speedster like a Percy Harvin? A receiver in the regular offense? A trick-play specialist? When he lined up split left, covered by smart veteran Tramon Williams, how could Williams know what to expect? The last significant tape on Nelson was from the 2014 Alabama-Birmingham season. “When I was in college,” said Palmer, who went to USC, “I remember Pete Carroll telling me, ‘Carson, don’t give the defense too much credit.’ What he was saying was, You can make plays too. Doesn’t matter what the defense does. Here, I can’t believe [Tramon Williams] is thinking a go ball to J.J. Nelson.” With the wind blowing hard across the field, Palmer threw the ball pretty far, to a point he thought only Nelson could get it. And he hoped the wind wouldn’t ruin it. It didn’t. Thing was, Williams pinned Nelson’s right arm so he couldn’t use both to catch the ball as he dove for it. So Nelson used one. The result: a ridiculous Beckhamesque one-handed catch.

“He’s not supposed to get that ball,” Palmer said. “Nobody’s supposed to get that ball.”

Both true. But that 38-yard bomb, with Palmer guessing through the crosswind, led to the first touchdown for the Cards. Last highlight for a while. Early in the second quarter, Arizona was down a touchdown. And frustrated.

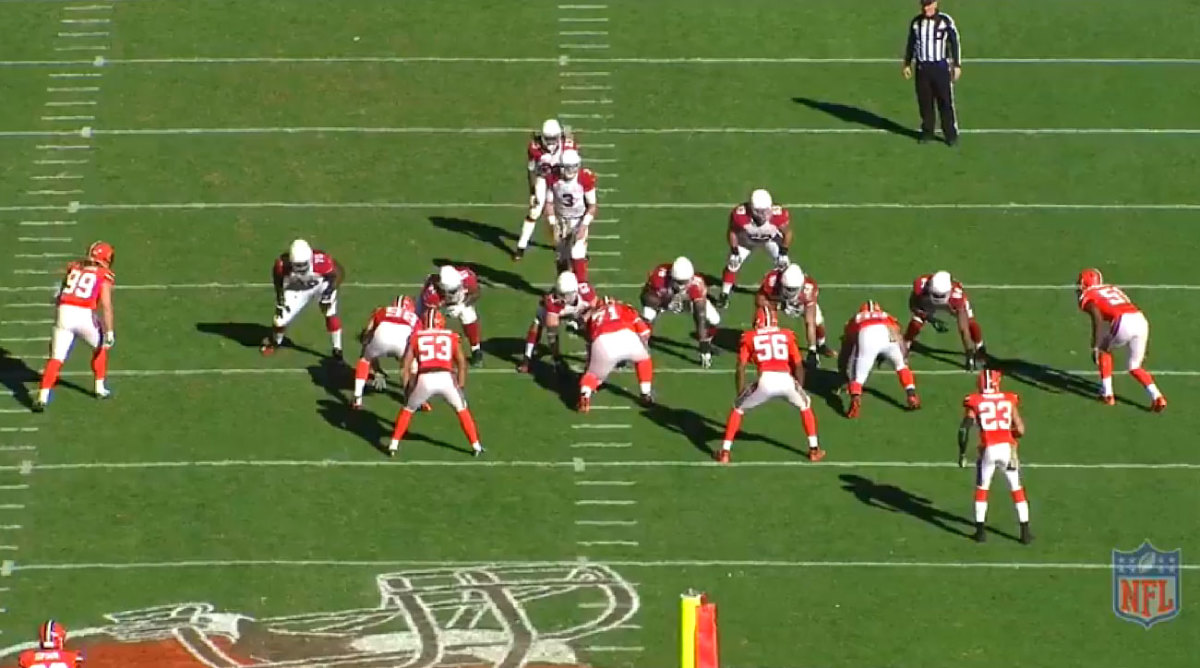

The 22nd play. The 11th pass. Arians’ favorite play in the game plan.

Pistol Strong Left Stack Act 6 Y Cross Divide.

As I explained in Part 1, Pistol means Palmer will take a short shotgun snap. Strong tells the fullback—backup center A.Q. Shipley—to line up to the tight-end side of the formation, the Left. The Stack is two wide receivers on the opposite side of the formation from tight end Jermaine Gresham. Act 6, the protection, tells the two backs which linebackers to block. Y Cross Divide is the combination route for wideouts J.J. Nelson (a deep diagonal from the front of the stack) and Larry Fitzgerald (a stutter-and-go—run seven yards downfield, deke toward the sideline, then sprint upfield).

At the line Palmer sees a few things immediately: For some reason, top corner Joe Haden is lining up to shadow Gresham, the tight end … Strong safety Donte Whitner isn’t in the box; rather, he’s lined up to cover Fitzgerald, apparently … And Palmer’s getting the single-high safety he wanted—free safety Tashaun Gipson is lined up in the deep middle. “All that matters to me is the middle safety,” Palmer says.

You’d think Palmer, seeing Whitner on Fitzgerald, would automatically go to that matchup. He will, but only if Gipson follows Nelson on the deep diagonal to help out Tramon Williams in coverage.

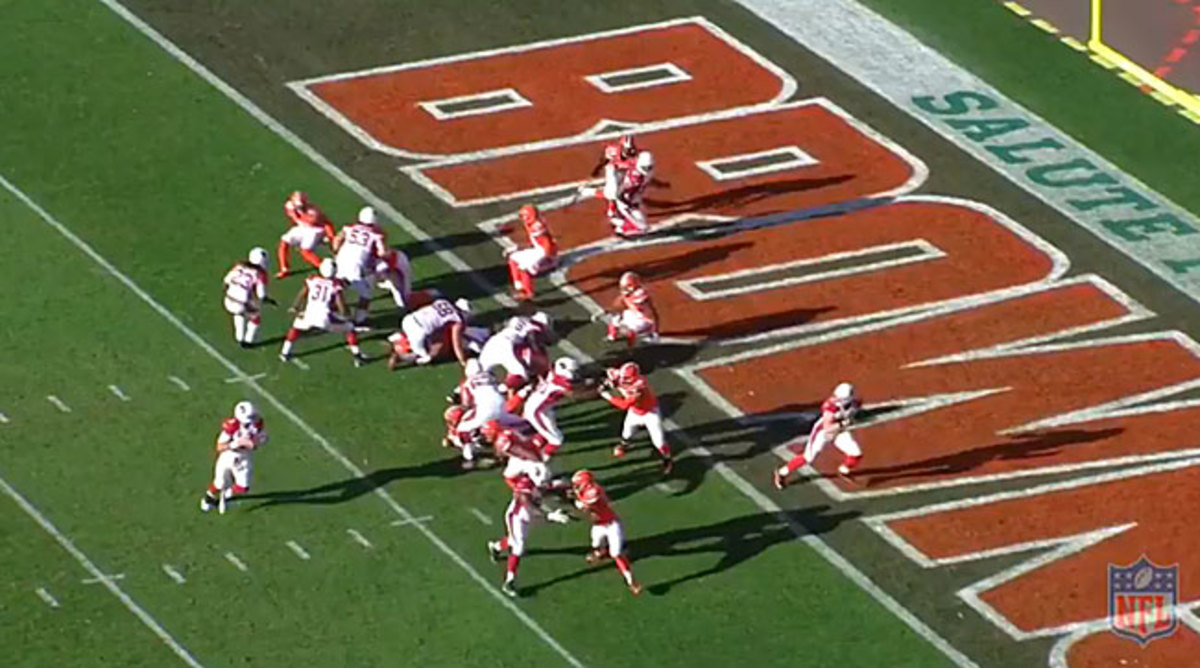

At the snap Palmer knows he’ll go to one of the wideouts (no sense in forcing the ball to Gresham with a good cover corner on him). A quarterback needs good protection to laser-focus on the safety 25 yards downfield, and running back Chris Johnson does a superb job erasing blitzing linebacker Craig Robertson.

Exactly 1.83 seconds after taking the snap, Palmer sees Gipson put his foot in the ground and pivot to follow Nelson. On to Fitzgerald.

The veteran receiver has a step on Whitner. A big step. And he’s faster than Whitner.

Exactly 1.50 seconds after Nelson shows his hand, Palmer lets it fly, high, for Fitzgerald. The ball gets up, and as it traverses its 53-yard path through the 21-mph winds, it floats and floats. Fitzgerald tries to find a fifth gear. Behind him, watching the play develop, Gresham throws both hands in the air, like, Touchdown! Touchdown!

The Cardinals Go for the Home Run

On Pistol Strong Left, Palmer gets the alignment he’s looking for: single safety deep, and another safety, Donte Whitner, on Larry Fitzgerald.

On Pistol Strong Left, Palmer gets the alignment he’s looking for: single safety deep, and another safety, Donte Whitner, on Larry Fitzgerald.

Palmer is waiting for free safety Gipson, just on the right edge of the frame, to show his hand: break on Nelson, or help with Fitzgerald up the near sideline.

Palmer is waiting for free safety Gipson, just on the right edge of the frame, to show his hand: break on Nelson, or help with Fitzgerald up the near sideline.

At this point both of Palmer’s options over the middle look open.

At this point both of Palmer’s options over the middle look open.

He’s clearly going for the Home Run ball, and free safety Gipson, out of the picture, has clearly committed to the cross.

He’s clearly going for the Home Run ball, and free safety Gipson, out of the picture, has clearly committed to the cross.

Gipson is back in the picture, but clear on the other side of the field.

Gipson is back in the picture, but clear on the other side of the field.

Palmer IDs the real target, who has broken free.

Palmer IDs the real target, who has broken free.

Fitzgerald has a good two to three steps on Whitner.

Fitzgerald has a good two to three steps on Whitner.

Realizing the ball is sailing, Fitzgerald leaps.

Realizing the ball is sailing, Fitzgerald leaps.

Even at full stretch, the ball is out of reach.

Even at full stretch, the ball is out of reach.

Nothing but turf for Fitzgerald this time. He’d get a TD later in the game.

Nothing but turf for Fitzgerald this time. He’d get a TD later in the game.

It’s hard to imagine any player at any position in football who tries harder than Fitzgerald. His effort—blocking, disguising, faking, running, catching, teammating, whatever—is precisely what every coach at every level of football should teach. “I was tracking it as I was running,” Fitzgerald said of the pass. “I had a great bead on it.”

With the ball in his sights but feeling it was eight, 10 inches too far, Fitzgerald began his dive. “At the last second, I don’t know, it just took off on me,” he said. “Even in warmups, the ball sailed. It’s different, playing in the AFC North.”

At the Browns’ 23 he leaped, his arms outstretched. At the 20, he was perfectly parallel to the ground, flying through the air. At the 19, the ball touched Fitzgerald’s right three middle fingers, and then quickly his left middle fingertip. Fitzgerald’s eyes widened, and he saw the ball hit the turf a millisecond before he ate some of that turf, facemask-planting on the green grass.

The pass had traveled 53 yards. It needed to travel 52 yards and eight inches.

Incomplete.

“As soon as he hit the dirt,” Palmer said later, “I said to myself, ‘I’m done with this wind today. No more high balls.’ I was disgusted with myself, wasting a play like that.”

Halftime: Cleveland 20, Arizona 10. In the locker room, Arians told the team: “If you want to be a pretender, go out in the second half and lose this game. Go ahead. If you want to be a contender, come out and dominate. Up to you.”

Good teams are not one-trick ponies. Good teams overcome the wind and four turnovers on the road against bad teams. Good teams are smart, and good teams are resolute, and good teams use the breaks handed to them.

The break came as the Cardinals prepared to start the third quarter.

“Coach,” wide receiver Michael Floyd said to Arians on the sideline, “Haden’s hurt. I think it’s a hamstring. I know I can run by him.”

Floyd had first noticed it in midway through the first quarter and told Arians and Palmer. Now he was saying it again. That didn’t surprise Arians; Floyd was always saying he could get open. Don’t all receivers? But Arians had Trips Right 70 Go, an absolute basic staple of the offense, in the game plan: three receivers on one side, one on the other, with the lone receiver the number one option because he’ll usually be single-covered. Arians knew if he flipped the call—three receivers left, Floyd alone on the right—Haden, most often the defensive left corner, would be lined up alone on Floyd. And then they’d see if Haden really was gimpy.

Fourth play of Arizona’s first series of the second half. Palmer in the huddle: “Trips LEFT, 70 Go,” Palmer said. As he got to position, Floyd nodded, sure of what was about to happen. Palmer is usually one to make sure he doesn’t dictate where he’s going with his eyes, but it wasn’t necessary here, because there was no safety help for Cleveland on Floyd’s side. It was Haden Island. At the snap Haden and Floyd jousted. Floyd took the outside route and got away with a tolerable pushoff 15 yards into the route. That’s when Palmer let it fly—only this time it wasn’t a rainbow, the kind of ball he’d thrown to Fitzgerald in the first half. It was more of a humpback liner, perfectly spiraled on a low trajectory, and it traveled 38 yards into Floyd’s waiting hands. Couldn’t have been a prettier throw. Haden, trailing by a step, dove to attempt the shoestring tackle but failed. Palmer to Floyd, 60-yard touchdown.

“Here’s what’s hard in a game like this,” Palmer would say later. “You go into halftime and feel like you’re down four scores, not two. But when you’ve played for a long time, that doesn’t really bother you. If you’d asked me at halftime, I would have told you: There is absolutely no doubt in my mind we will win this game. Absolutely none. I’ve gotten used to the rhythm of the game over the years, and it’s never, ever over at halftime. All I ever think of is, ‘One play. One drive.’ Nothing else. You’re a young guy and maybe you press. You think you’ve got to get it all back right away. Well, you can’t. Just play … play football.”

Five drives to start the second half, three touchdowns. On third-and-goal from the Cleveland 1, as the Cardinals drove to take the lead midway through the third quarter, came a perfect illustration of why Palmer and Arians work so well together. On first down from the nine Chris Johnson ran for four. On second down from the five Johnson ran for four. Third and goal from the 1. Now what?

Jumbo package in for Arizona. Arians sends in three plays, with options for Palmer.

• Palmer will hand it to Johnson if he thinks there’s a crease through which Shipley, lined up at tight end on the left side, can pave the way to a touchdown.

• If Palmer doesn’t hand off, he’ll do play-action with Johnson and run a bootleg to the right.

• If Palmer has a tiny lane, he’ll run it in. If not he’ll try to flip it to blocking tight end Troy Niklas. The key: forcing one of two linebackers who’s not in the nine-man Cleveland front, Craig Robertson, to honor the threat to run.

Eight man front for Arizona. Two backs behind Palmer, under center. Looks very much like a run. Palmer doesn’t see the gap for Johnson, so he keeps it and rolls right. The play-action fools Robertson, who drives toward the line. Niklas is more alone than any other other receiver has been all day. Touchdown. And that is that.

Palmer is not an effervescent man, but after the game, when I first saw him by his locker in the Cardinals’ dressing room, he was as buoyant as he’d been all week. “Bruce was in such a groove today,” Palmer said. “He was awesome! Every play he sent in I was sure would work. In all my years of football, I’ve never been a part of a game where the play-calling was this good—ever. He had such a great feel for us today.”

“Pretty good to have that guy at quarterback too,” said the other half of the mutual-admiration society.

The plane flight home was fun. Not one conversation about football, but lots of card-playing back in coach. “You need a break after a week like that,” Palmer said. “We played Boo-Ray the whole ride home.”

As I digested the week and the game and the story I’d reported, I kept coming back to this: Arizona has a coaching staff that works feverishly in a short week to build the game plan; the average NFL head coach and staff, collectively, make something in the range of $12 million. There’s a pro personnel department that scouts the previous Browns games and works all night Sunday to have an in-depth, collated scouting report on the desk of every coach by 6:30 a.m. Monday. There’s an analytics element, with a staffer working that side. There’s the estimated $300,000 cost for the STRIVR virtual reality system, new this year. There are 171 plays in the game plan, not one of them because of someone’s “gut feeling” or because “this worked last week.” No. There’s football science to every single play.

Now, what were the big factors in Arizona’s 34-20 victory over Cleveland? I might argue there were two: the wind, and Joe Haden’s hamstring. The Cardinals, putting together the game plan, didn’t say on Tuesday, “That place is a wind farm, so we better not put as many downfield shots into the game plan.” As usual Arizona had six Home Runs, the usual number, in its plan … and called three during the game. But Palmer had to fight the wind constantly, and it changed the way he threw the ball as the game progressed; the fact that he conquered the swirling winds to throw for 374 yards and four touchdowns tells me he’s not a robot or a football wonk beholden to his study materials—he’s a smart guy who knows how to adjust to the prevailing conditions of the day.

And what’s the thing you do in a pickup football game after school? You come back to the huddle and tell the quarterback, “Throw it to me! I can totally beat my cover guy!” That’s what Floyd said to Palmer and Arians. The coach and QB trusted him, and Palmer hit Floyd for the touchdown that turned the tide of the game.

“The wind and a hamstring,” Arizona GM Steve Keim said when I ran my Rube Goldberg theorem by him. “That defines what an inexact science the game is.”

More King:Game 150—A Week in the Life of an Officiating Crew | Inside Replay HQ | The Making of the 2015 Schedule

So I’m left to think about how compelling and wonderful the strategy is, and I cannot imagine a quarterback being better prepared for a game than Palmer was for this one. But also, I am left to think how utterly and inescapably unpredictable the sport of football is—and how that makes it so appealing.

I give the last word to the star of this show.

“You can’t make football predictable or a science, and that’s what we love about it,” Palmer said, looking back on the week. “A lot of times it’s, who can manage disaster better? Like, Cover 4? What?!!! All they’d shown on tape was Cover 1 on this play! No! And you see a young quarterback frozen by it. Me, that’s not going to bother me anymore.

More Palmer:On Technology | On O-Line Protections | Part 1

“I realize my limitations. I have to be sound in everything I do. Being sound is just working, studying, preparing. There is no way anyone outworks me. Honestly, I like getting myself freaked out early in the week, because then, whatever it takes to not be freaked out, I’ll do. I remember when I was a young quarterback, going to bed Saturday night, I used to think, ‘I better be 95 percent sure of everything coming tomorrow.’ Now it’s 100 percent.

“I’m always thinking, ‘I got this, I got this.’ ” ♦

MISSED PART I OF “A QUARTERBACK AND HIS GAME PLAN? READ IT HERE.