The Big Picture

What’s changed in the three years since the Supreme Court granted all 50 states the right to legalize sports betting? Everything. By the end of 2021, online or in-person wagering will be sanctioned in more than half the country. Revenue is skyrocketing. Leagues are evangelizing. And booming business means big changes for anyone who operates, plays, covers—or bets on—the games we love. Welcome to the Gambling Issue.

It was 2012, and New Jersey was seeking to legalize sports betting. One by one, the commissioners gave depositions, offering their doomsday predictions. Bud Selig, then atop Major League Baseball, asserted that he was “appalled” by the idea of expanding sports wagering outside Nevada, adding that gambling is “evil, creates doubt and destroys your sport.”

The NBA’s David Stern agreed and then went and made it personal, scolding New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, “The one thing I’m certain of is New Jersey has no idea what it’s doing and doesn’t care because all it’s interested in is making a buck or two.”

In 2021, a mere nine years later, their successors would have a very different conversation on the subject. In April, the NBA’s Adam Silver ribbed MLB’s Rob Manfred about baseball’s leisurely pace of play. As Manfred recalled to Sportico, Silver told him, “Rob, you gotta stop talking about the pace of game. Your pace of game is going to be absolutely perfect for sports betting.” In other words, all that time between pitches might be maddeningly at odds with our hyperstimulated culture—but it is a tailor-made interval for fans to place a wager.

Then there’s the NFL, the league that once suspended its reigning MVP for gambling and, as recently as 2015, wouldn’t let Tony Romo host a fantasy football convention at a Las Vegas casino. Today, the NFL has betting partnerships with dozens of sportsbooks and happily fills broadcasts with ubiquitous commercials for DraftKings and FanDuel. And there is now an NFL team within a dice roll of The Strip, with a Vegas Super Bowl likely coming soon.

With the kind of blinding speed that would raise eyebrows at the combine and induce the kind of whiplash that would lead to a stint on the injured list—which always existed for only (ahem, ahem) journalistic purposes—sports have made a stunning reversal on the collective stance toward gambling. What once was cast, publicly anyway, as a great taboo threatening to undermine the integrity of games? It is now not merely accepted behavior, but a cornerstone of growth strategy.

Read More From the Gambling Issue

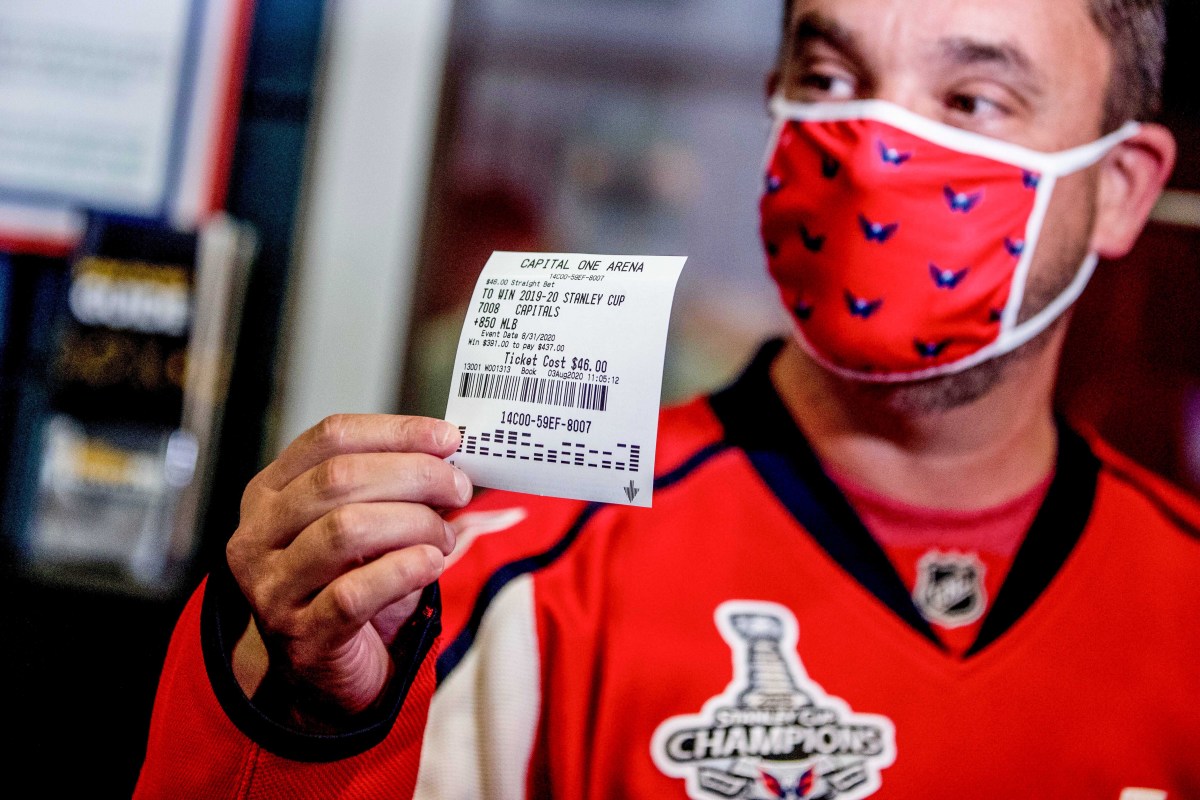

To borrow a phrase from another form of wagering, teams and leagues are all in. Every major league has partnerships with sportsbooks and data companies. To pick one team among dozens, the Chicago Cubs’ deal with DraftKings exceeds $100 million a year. In Washington, D.C., a 20,000-square-foot sportsbook resides inside Capital One Arena. Ted Leonsis—owner of the Wizards, Mystics and Capitals, and a known sports gambling evangelist—told The Washington Post he has only one regret: He wishes the facility were bigger. The athletes, not unreasonably, want a piece of the action, too. Collective bargaining agreements may soon hinge not on salary caps, but on how to split gaming revenues.

The motivation behind this shift barely merits mention, but it’s money, of course—the same reason fans place $100 bets on a team to cover a spread. (Or, increasingly, whether the next pitch will be a strike. In-game betting is fast becoming more popular and lucrative than simply speculating on outcomes and lines.) Firm numbers are hard to come by, but we can extrapolate figures from the states—nearly 30 and counting—that have legalized some form of sports wagering. New Jersey oversees a handle of roughly $1 billion a month. Assuming the states operate on a 5% margin, that’s a lot of incentive for legalization. (And that’s $1 billion a month during a pandemic, with technology still emerging.)

“Everything was shut down, with no fans, and the leagues kept cranking out games,” says Ryan Rodenberg, a law professor at Florida State, who’s carved out a timely specialty as a sports betting expert. “That would have seemed bizarre decades ago, but they can just make so much money off streaming rights and data rights [even] with no fans.”

On the other side of the ledger, for fans, sports betting presents a way to add a level of engagement and, if all goes right, a few extra bucks. “There’s a glut of people who grew up playing and watching sports; they’re no longer playing, but they want to feel like they’re part of it,” observes Rodenberg. “Sports betting is the perfect vehicle.” It’s not just a participatory window for the Super Bowl or NBA Finals or World Series. Some of the world’s biggest bookmakers offer odds on some of the lowest-level contests imaginable. You can find a line on everything from cornhole to Australian neighborhood beer league soccer.

While Stern and Selig may have been a bit alarmist, this move to the mainstream does come with potential perils. The chief concern: Where there is action, there is the potential for vulnerable athletes. Earlier this summer at the French Open, Paris authorities entered the women’s locker room and arrested a little-known Russian player. She was accused of committing “sports bribery and organized fraud” at the previous year’s tournament, conspiring with gamblers to manipulate the outcome of her doubles match and, having returned to the scene of the (alleged) crime, was apprehended.

Then there are fears about the sports gamblers themselves. Since 2018, when the Supreme Court effectively gave states in addition to Nevada the right to legalize sports gambling, all but three have introduced some form of legislation. (If you had Idaho, Utah and Wisconsin in your trifecta box, you win!) There were floodgates, but no guardrails. Some experts believe that the intoxication of wagering, coupled with mobile technology, has already led to a spike in problem gambling.

And yet the same free-market principles that undergird sports gambling may also prove the most effective policing. It is unlikely that athletes in the most prominent leagues are going to risk their seven- (and eight- and nine-) figure salaries—to say nothing of their reputations—fixing games. College athletes (and Australian beer league soccer players or low-level tennis players) may have more incentive to act corruptly, but in theory the betting markets will dry up for leagues and sports vulnerable to tainted results.

Without diminishing the seriousness of problem gambling, is betting on the Milwaukee Bucks (or Shohei Ohtani’s next at bat) manifestly different from speculating about a tech stock on Robinhood or buying up cryptocurrency named for someone’s dog? What is more American than speculating on an outcome yet to be determined? There’s also the if-you-can’t-beat-’em-join-’em argument. Hundreds of billions are already going to be wagered on pro sports, anyway; bringing it out of the shadows, adding regulation (and detection) and taxing proceeds are to society’s benefit.

To Sports Illustrated’s credit, we saw this coming. In 1974, the magazine played futurist and tried to glimpse sports in the year 2000. Among the predictions: “The most likely source of income for sport in the future will be gambling money. Few realists doubt it.” Bill Veeck, the famously progressive MLB owner and promoter, concurred, adding, “There undoubtedly will be legalized gambling on all sports. . . . There will be mutuels in our stadiums. There’s not a thing wrong with it.”

It might have taken a while, but here we are. And “gambling money” will figure only more prominently in sports’ future. A safe bet, that.

• How the League Went On Defense

• Do Today's Fans Blame Athletes More For Betting Misfires?

• A Pizza Joint in Jersey: The Place To Place Your Bets

• The Beats Go On