... and In This Corner

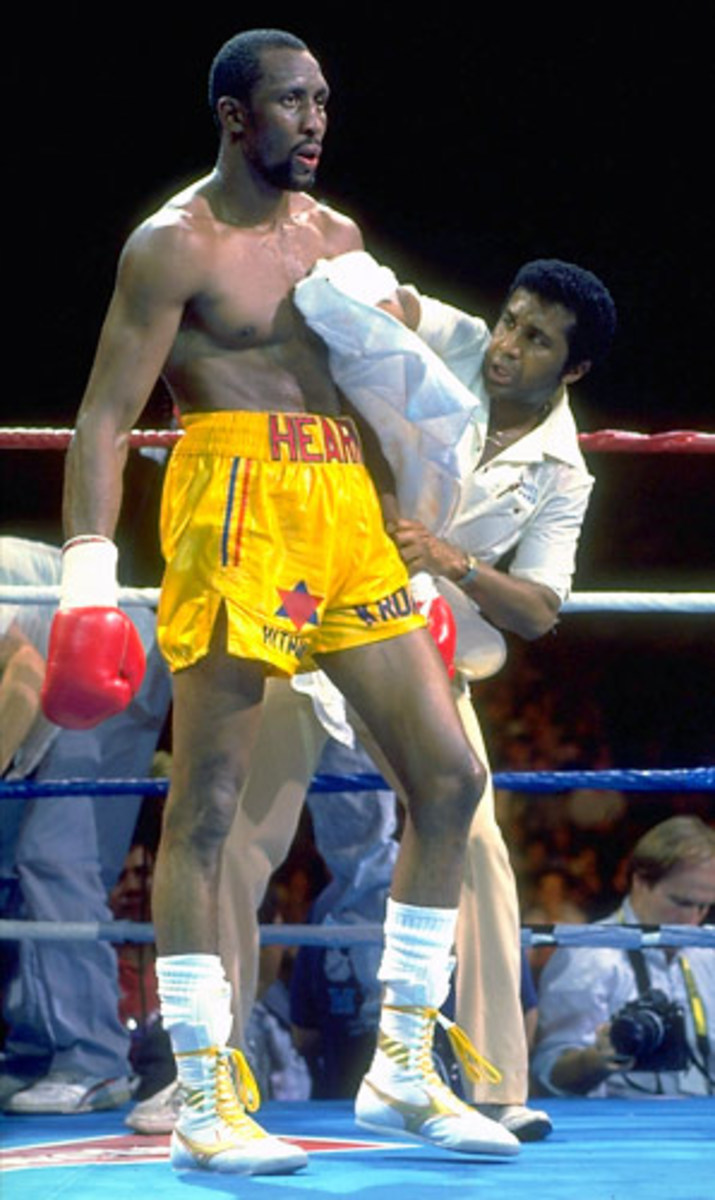

We honor the passing of legendary trainer Emanuel Steward by looking back at one of the most memorable stories in Sports Illustrated history. This piece originally appeared in the Sept. 14, 1981 issue.

* * * * *

I went to a motivational training course once, a course of self-discovery, and I found out after a week that my fear -- it was not a fear of not being accepted -- was a very violent fear of failure.-- EMANUEL STEWARD, trainer/manager of Thomas Hearns

For Emanuel Steward, Thomas Hearns is the embodiment not only of Steward's craft as a trainer -- he is the only trainer Hearns has ever had -- but also of his savvy and judgment as a manager. Steward has trained and managed professionally for less than four years, since Hearns turned pro on Nov. 25, 1977, but he has already raised two world champions out of Detroit's celebrated Kronk Gym. The first, Hilmer Kenty, won the WBA lightweight title from Ernesto Espana on March 2, 1980. Five months later to the day, Hearns knocked out Pipino Cuevas to win the WBA welterweight championship. Kenty has since lost his title (to Sean O'Grady), but the undefeated Hearns has defended his three times (Luis Primera, Randy Shields and Pablo Baez). Meanwhile, Steward has put the Kronk and most of its fighters on hold. "It's right to say I'm in transition," Steward says.

That's hardly new. In one form or another, Emanuel Steward has been in passage for almost all of his 37 years. He was born just outside the coal-mining West Virginia town of Bluefield, on July 7, 1944, the eldest of three children of Catherine and Emanuel Sr. No one in the family boxed, or urged young Emanuel to, but he began when he was eight, after his parents gave him a pair of Jack Dempsey-model gloves. The gift enthralled him and set the direction of his life. When he wasn't picking wild strawberries in the surrounding hills or plucking fish out of a nearby creek with his bare hands, he was rearranging the shape of his mother's pillows or inviting friends home to have their noses bloodied.

"I had a wonderful time in West Virginia," Steward says. When he was 10, his parents separated, and his mother and the children went to Detroit by train. "I'll never forget that long, lonely ride," Steward says. "We left on Friday and it rained the whole trip. We got to Detroit on a Saturday evening. I didn't know what was going on. I thought it was the end of the world -- not knowing that it was the beginning of a new life."

Steward brought with him the urge to box, and by the time he was 12 he had found his way to the Brewster Gym, where Joe Louis got his start. The gym fascinated him -- the fighters in headgear, the rhythm of the men working the bags and skipping rope, the sparring in the rings -- and it drew him back. As an amateur bantamweight, fighting first as Little Sonny Steward, later as Sonny Boy Steward, he developed into a good student of the stylists of the day.

"I used to love to see Willie Pep and Ray Robinson," Steward says. "To me, the epitome of a great athlete is a great boxer. I just love the rhythm of seeing a man dance, slip punches. I loved the dancers and boxers. I would see them and be mesmerized."

They influenced his style. Robert Watson, today the chairman of the Michigan State Athletic Board of Control, refereed a number of Steward's fights. "A good boxer, a jabber -- smooth, slip-and-counter," Watson says. "He wasn't a slapper. He punched sharp, but he didn't hit hard. He knew all the things to do."

Steward won 94 of 97 amateur fights, and crowned his career in Chicago by winning the 1963 national Golden Gloves bantamweight title.

Steward didn't turn pro, becoming instead a coach. In 1963 he guided five juniors, ages 10 through 15, to five titles in a tournament sponsored by the Detroit Parks and Recreation Department. His first fighter was 14-year-old Elbert Steele Jr., to whose sister, Marie, Steward was engaged. Elbert was undefeated in 20 fights under Steward.

Marie and Emanuel were married in 1964 -- she still wears, on a necklace, the diamond-studded Golden Glove he won the year before -- and they settled into a six-room apartment in Detroit. Steward had graduated with honors from Eastern High School in 1962 and knocked about in odd jobs: as a laborer in the folding-door company where his mother worked; later as a die-setter; as a quality control inspector at an auto-parts plant; and on the assembly line at Chrysler. He was working for Chrysler when he took the job that changed his life -- laborer with the city utility, Detroit Edison. By 1965 his first daughter, Sylvia, had arrived, and the following year Steward began to climb utility poles. He also enrolled in the electrical apprenticeship program at Henry Ford Community College, working days while going to class at night.

"I decided, if I'm going to be there, I didn't want to be no damn laborer," Steward says. "When I started, I sat in class and didn't even know what they were talking about. I was so embarrassed. I had been an honor student, but the standards at inner city schools had been so low. I had never done any algebra or geometry, and I couldn't participate in class. I used to go home and study related books till three o'clock in the morning, trying to understand. It was rough."

For three years Steward stayed away from the gym. "I didn't even miss it," he says. "I bought myself a new little brick bungalow, in a nice section of the city. I bought a German shepherd puppy. I had a new little LeMans sports coupe, burgundy and black. I had a career at Detroit Edison. In 1969 another kid [Sylvette] was on the way. The Great American Dream. I was really happy. And then fate intervened."

Steward's father, who had remarried, called from West Virginia and asked him to look after his 15-year-old son, James -- Emanuel's half brother. Steward agreed. One day in the fall of 1969, James quietly asked Emanuel, "Can you take me somewhere to get some boxing lessons?" They were living on the far West Side at the time, and there happened to be a gym nearby. It was named after a former city councilman, John F. Kronk.

Soon Steward was immersed in boxing again. James won the 1970 subnovice Golden Gloves title in Detroit. Steward became a part-time coach at Kronk at $30 a week, and in 1971 seven of his kids won Golden Gloves titles. "I got so engrossed in it then," he says. "I started taking the kids on weekends to little tournaments, trying to get them more experience, running here, running there, and it got back into my system."

Steward was climbing steadily at Detroit Edison -- he was a master electrician by then, a project director supervising 200 employees; he also had a new gold Cadillac and a salary of $500 a week -- but the gym was becoming more demanding. Marie didn't like it. "We had a regular check coming in, with overtime," she says. But Steward took $5,000 from their savings and invested it in a cosmetics distributorship. Then, on March 3, 1972, he resigned from Detroit Edison and started to devote all his attention to his amateur program at the Kronk.

"I decided to see how far I could go in this," he says. "My dream was to take an amateur team and make it nationally famous. The deep dream of everybody is always to have a world champion, but I never really had any specific plans for professional boxing."

Elbert Steele Sr., Steward's 68-year-old father-in-law, recalls when the two used to fish for crappies and bass from the banks of the Detroit River. Emanuel would let Steele off by the bank and then drive a block or two to park the car.

"By the time he got to the river, I'd have caught three or four fish," Steele says. "This went on a few days. One day I said to him, 'Man, Sonny, you're so slow. What are you gonna do when you're my age?' He said, 'When I get to be your age, I hope I don't have to do nothin'.' His ambition was to be rich. He knew he couldn't get there working for someone else. If he'd just wanted to make a living, he could have stayed at Detroit Edison. He'd have been making $1,000 a week by now. He'll make more out of this fight than he could have working a hundred years."

"It's just something that happened," says Marie. "It wasn't like, 'I'm gonna get in there and build these fighters up and, wow! we're gonna be rich one day.' He loved boxing, and I think that's why it happened."

Whatever, if a very violent fear of failure possessed Steward, it didn't govern him. Detroit Edison meant success, security, and he left it to court what he feared most. It wasn't an easy time. The cosmetics distributorship failed, so he did electrical work and sold health insurance on the side. The gym work paid him $1,500 a year, and he used what other money he could scratch together to support his family and finance the weekend excursions of the Kronk Boxing Team.

It didn't take Steward long to build perhaps the finest amateur boxing program in the land. Interwoven with the themes of unity and order and inspired by ferocious competition, the Kronk, under Steward, became a kind of paradox: a Boy Scout troop set in a Darwinian laboratory. The boys hung out together, cheering for each other from Chicago to Cleveland, and Steward insisted that they behave decorously and dress neatly, in the Kronk red, gold and blue.

"It was a unit," says Don Thibodeaux, a trainer at Kronk and one of Hearns's cornermen. "Emanuel in the corner giving instructions to fighters sparring in the ring. Trainers on the floor working with their fighters. It was like an unbeatable team, a family -- spar, work, play and fight together. And then go out of town and come back with all the trophies." "I think it's important psychologically that people feel unity," Steward says.

Steward was the sustaining voice and presence of the Kronk. And he was also its master trainer and technician, teaching his youngsters -- Hearns, Kenty, Mickey Goodwin, Milt McCrory and the rest -- how to fight. He encouraged them to think for themselves and find the routines that suited them.

"I'm not a fanatic on certain things, like skipping rope," Steward says. "For instance, Thomas doesn't like to skip rope; he never liked it." So he doesn't do it. Nor does Hearns like the speed bag, so he doesn't do much of that. If there is one abiding theme in the gym, it's the withering work in the ring. Those not fit do not survive. "They don't have heart, they don't make it through the gym," Steward says. Frequently, as with Hearns, Steward will have his fighters work with bigger and heavier opponents.

Kronk fighters all tend to look like Ethiopian long-distance runners; the spike-thin Hearns is the archetype. Steward's critics say he emaciates his charges, working them too hard in a gym he keeps too hot -- more than 90????. "All I can say is, I have a very good track record and I'm not changing," Steward says. "There's not as much oxygen in that hot gym and I think it's great for conditioning. I believe in a lot of boxing. You can train and work on the speed bag and heavy bag, but when you get in the ring with another fighter, it's a different story. Punches are coming at you, there's physical contact, muscle against muscle. It's like a guy shooting baskets. He can sit in the backyard and shoot baskets and he can be a genius at it, and then he gets in an actual game and guys are coming at him from every direction and now he's got to shoot fast, from every position, and it's a different ball game. So I think that sparring a lot is very, very good. Even if you wear headgear, blows are partially going through, and I think the muscle and tissue alongside the jaw get strengthened.... I've never had a guy knocked out in a professional fight."

Some Kronk fighters carry their left hand hazardously low, but Steward says he doesn't teach this. "It's more a Hearns characteristic," says lightweight Davey Armstrong, a U.S. Olympian in 1972 and 1976 who began training at the Kronk last year. If Steward has a passion, aside from an insistence that his fighters attack the body -- "Go to the liver!" he yells to them repeatedly -- it's balance.

"I think the real key is to have the weight evenly distributed between the left and right legs at all times," Steward says. He believes that balance is the key defensively -- to getting out of trouble -- and offensively -- to making trouble. "Thomas holds his left hand low sometimes, but his weight is so evenly distributed that he can move to the left and right, step straight back, step in. A lot of his knockouts have come because when he punches, he gets such beautiful position and leverage. Most of your heavyweight fighters today don't punch that good because they're off balance, off on one leg or leaning to the right, imitating Ali. But Thomas is like one of the old-timers: good position, leverage and balance, his weight evenly distributed."

Techniques aside, Steward has gotten so much out of so many fighters because he has made himself a student of them all, searching for what moves them. He sees Hearns motivated by the same fear that drives him: failure. For Goodwin, his middleweight, it's money. On Aug. 22, at the Glacier Arena in Traverse City, Mich., Goodwin tangled with a tough, inspired, if unknown, middleweight named Jimmy (School Boy) Baker. It was a close fight, and going into the last round Steward chanted into Mickey's ear, "Look, you're blowin' this damn fight! You know that apartment you want? You know that bar and restaurant you wanna buy? All of that is gone, man, if you don't win this fight! You're standing on the threshold of a good TV fight and you're gonna screw it up. You're blowin' it, Mickey!"

"I'm tryin', I'm tryin'," Mickey choked. "What should I do? What should I do?"

"Do what I been tellin' you. Don't hit him and then lay on top of him and smother your work. Hit him and step back, hit him and step off to the side!" Fighting like a man possessed and doing what he was told, Goodwin stopped Baker in the final round.

Steward insists that when he started at the Kronk, he had no intention of turning it into a professional enterprise. But then his amateurs outgrew the three-rounders, and had to make a living -- and Steward went pro with Hearns in 1977. "Otherwise, I'd be making champions for someone else," he says. "Let's be realistic: someone else would be coming and stealing everything."

Steward thought he had a license to print money, but it was a long fall and winter in 1977. One day Steward and Thibodeaux set off by car from Detroit to New York, dragging a U-Haul. Thibodeaux is a sculptor, and the rig contained a 1,200-pound metal sculpture of Muhammad Ali, made of welded automobile bumpers, depicting Ali throwing the punch that felled George Foreman.

Thibodeaux was bringing the piece to sell it, while Steward was bearing a scrap-book of Hearns's amateur exploits, hoping to sell his fighter to network television. Leonard and his fellow Olympic gold medal winner, lightweight Howard Davis, had turned pro the year before and signed lucrative TV contracts. Steward wanted some of that action. He and Thibodeaux must have looked a sight as they walked down the Avenue of the Americas: the 5'8", 155-pound Steward very neatly shaven and dressed in a trim dark suit ("He looked like a Muslim," Thibodeaux says), the 5'8½" sculptor, weighing 235 pounds, 100 above his amateur fighting weight, wearing a cranberry-colored dashiki beneath a chin festooned with a foot of flowing red beard.

Thibodeaux showed his sculpture in Madison Square Garden but didn't sell it until much later, for $40,000, to a Michigan doctor, and Steward didn't make it with the networks. "CBS told me not to bother," he says. "NBC let me talk to them, but they weren't interested in getting involved in a fighter. With ABC I got into the lobby. I talked by phone with someone upstairs, and he told me to leave the scrapbook. I never did. I wanted to cry. Don and I said the hell with it and went back home. I used to be bitter, but no more."

Now Hearns has his chance. As for the Kronk, many of the fighters there feel they've been pushed aside in Steward's rush to get Hearns to the top. Steward hardly goes to the gym anymore, and his absence has been an emotional wrench for those to whom he had grown so close. Kronk fighters feel neglected and rejected. Steward sympathizes but says the game has changed, that all hinges on what Hearns does against Leonard, that Kronk will never be what it once was.

He asks only that you hear this: "I want to finish up with the amateur kids I have now, so then I will have given every one of them a chance to go as far as they can go in professional boxing. (Pause.) Then, after that, I want to retire from professional boxing. I think six or seven years. Then go back to amateur boxing again. Get me some little kids about 10 years old. That's what I really want to do! Get me another Kronk."