Pacquiao's greatest friend: The only man who's witnessed his entire career

LOS ANGELES – The boxer and his best friend settle into the back booth at their favorite Thai restaurant, same as hundreds, even thousands, of nights before. They’re watching funny YouTube videos on the flat screen, short clips of unfortunate accidents, including a guy sleeping in a wheelbarrow dumped down a hillside by his buddy.

The boxer, Manny Pacquiao, explodes in laughter at that clip. But Buboy Fernandez, his best friend, laughs nervously. He has been the victim of a Pacquiao prank or five.

• BISHOP: Pacquiao-Mayweather is the only treatment for Roach's pain

Pacquiao has fought 64 times in his professional career, and only one person—not his mother, not his brother—has witnessed all 407 rounds in person. That person is Fernandez, who will spend May 2 again in Pacquiao’s corner for their most-anticipated fight, against Floyd Mayweather Jr. in Las Vegas. “Buboy is the longest,” Pacquiao says. “He’s been with me 20 years.”

Pacquiao says this earlier that day inside the locker room in the basement gym at the Wild Card Boxing Club in Hollywood. The room is small, about the size of a prison cell, maybe five feet by five feet, or the equivalent of the quarters they once shared.

“Call Buboy,” he says to no one in particular. Someone does, and Buboy jams himself into the corner of the room, near the lockers mere feet from Pacquiao, but as if he wants to hide. Pacquiao points at Buboy’s belly, once flat, now inflated to roughly the size of a basketball. Proof of the spoils of their success.

“Let me tell you the story of Buboy,” Pacquiao says, as a wide smile breaks across his face. He points across the room. “Buboy’s body is not like that. His body is like mine.”

“That was a long time ago,” he says.

****

By age 16, Pacquiao trained some at a gym for amateur boxers in Manila. On one break, he returned home to General Santos City. He went out and searched for his brother, Bobby, whom he passed on a street corner and did not recognize.

Bobby Pacquiao was with a friend, drinking and smoking cigarettes, their clothes caked with mud, whiling away another lost afternoon. That friend looked familiar to Pacquiao.

It was Buboy Fernandez.

Freddie Roach explains his strategy, bond with Pacquiao after 14 years

He says he did not own a single pair of underwear back then. “Commando,” Pacquiao notes, with another smile.

That was 1995 or so, they aren’t exactly sure. Buboy had dropped out of school and set up on the streets. He smoked. He drank. He played cards. He had, he says, no dreams, no plans, no ambitions beyond Gen-San.

Pacquiao decided to bring both Bobby and Buboy to Manila, “because,” he says, “I am worried about them. There are drugs, liquors, death, many things like that.”

So they went. “Saved my life,” Buboy says.

Pacquiao did more than box in Manila. He worked construction, as a welder and a builder. He painted. He tailored clothes. He does not find it a coincidence that all of those jobs, the boxing included, involved his hands. He sent most of the money he earned back home, to his mother, for rice and other food. His family’s survival depended on it.

He found Buboy and Bobby work. They washed his clothes. They cleaned his dishes. They mopped the tiny room they all shared, the one with the hard floor and the bamboo bed. The room itself was a luxury at the training center. Only champions received one. The rest of the prospects, Buboy says, napped in the rings, using stacks of milk cartons for pillows, sleeping on someone else’s sweat.

is hiding somebody in there. I know it. If I find that guy, I’m going to kick his ass!’”

Pacquiao helped Buboy become the gym’s janitor, and each day, after training concluded, he mopped the floors and cleaned the bathrooms. If Pacquiao received two cups of food for each meal, he ate one and shared the other with his comrades. No wonder that for his first bout, in January of 1995, he weighed in at 106 pounds.

Buboy, 36, is older than Pacquiao by five years. “But in Manila, I’m like their father,” Pacquiao says. “I’m telling them what to do.”

One day, Pacquiao sought out Buboy after he finished his janitorial duties. He sat Buboy down. His serious face indicated a serious conversation.

“Are you happy with what you’re doing now?” Pacquiao asked.

“Maybe. I don’t know.”

“Become a trainer,” Pacquiao said.

“No.”

“Why?” Pacquiao asked.

“It’s too hard for me. I don’t know what is this boxing.”

“Come here,” Pacquiao said. “I’ll teach you.”

And so he did. He instructed Buboy to hold the mitts that fighters punch and showed him the routines that boxers follow and how to orchestrate that day-to-day tedium that comprises readying the body for combat. On the first day, and for several days thereafter, Buboy cried. Too difficult, he found it.

“You are happy washing my clothes and cleaning the gym?” Pacquiao asked him.

“No.”

They resumed their mitt work.

“One day,” Pacquiao told him, “you will be thankful for me.”

Neither of them could have expected what happened next. That Pacquiao would travel to the United States and seek out a trainer and climb the steps to Wild Card and meet Freddie Roach. That Pacquiao would return to Gen-San and tell Buboy to hurry to the U.S. Embassy to get his papers in order because he had found a coach. That they would travel the world together, as Pacquiao won titles and climbed up weight classes, as he knocked out Ricky Hatton and stopped Miguel Cotto and battered Antonio Margarito and transformed from a 100-pound teenage boxer into one of the world’s most fearsome welterweights.

“When I fight, I’m not thinking for myself,” Pacquiao says. “I’m thinking of my mother, my brothers. Like I’m a father. To everybody. I’m worried about them.

“I’m worried about Buboy.”

****

Who wins: Mayweather or Pacquiao? in SI Polls on LockerDome

Odd side note: before Buboy dropped out of school, one of his teachers was Mrs. Donaire. As in, the mother of Nonito Donaire, another future champion known as the Filipino Flash. Pacquiao smiles at the memory, then mimics someone getting their wrist slapped repeatedly—which is his explanation for Buboy’s limited experience as a student.

Floyd Mayweather a big challenge for Pacquiao trainer Freddie Roach

One weekday last month, Buboy arrives before Pacquiao and heads into the basement gym, a former Laundromat that Roach renovated and transformed into a private space for his best fighters. Buboy, who rarely grants interviews but spoke with SI.com for 30 minutes, settles into the corner, behind a workout machine, as if he doesn’t want anyone else to notice.

The young man who once cleaned a gym wants to reveal something in that corner: that after this Mayweather bout, he will open his own training center in the Philippines, with $150,000 in seed money from his best friend, Manny Pacquiao. He will live there with his wife and his four children, and he will train boxers in the way that Pacquiao taught him to. “I need to teach those like me before,” he says. “From nothing. With nothing.”

For now, that can wait. The Mayweather fight, six years in the making, draws closer. Pacquiao seems at once relaxed and engaged, freed from the distractions of previous bouts, all the gambling and carousing and late nights replaced by Bible study and a camp weight-loss competition.

Buboy leans back, both arms over the top rope, as Pacquiao crunches through a few hundred sit-ups. This, Buboy says, is their most important fight together. But they’re still together, always together. In fact, someone once asked Pacquiao a question. If he had one spot next to him on an airplane, and he could bring only one person, his wife, Jinkee, or his best friend, Buboy, whom would he chose?

“We’ll wait for the next flight,” Pacquiao answered. “I cannot fly without him. It’s like I fly without wings.”

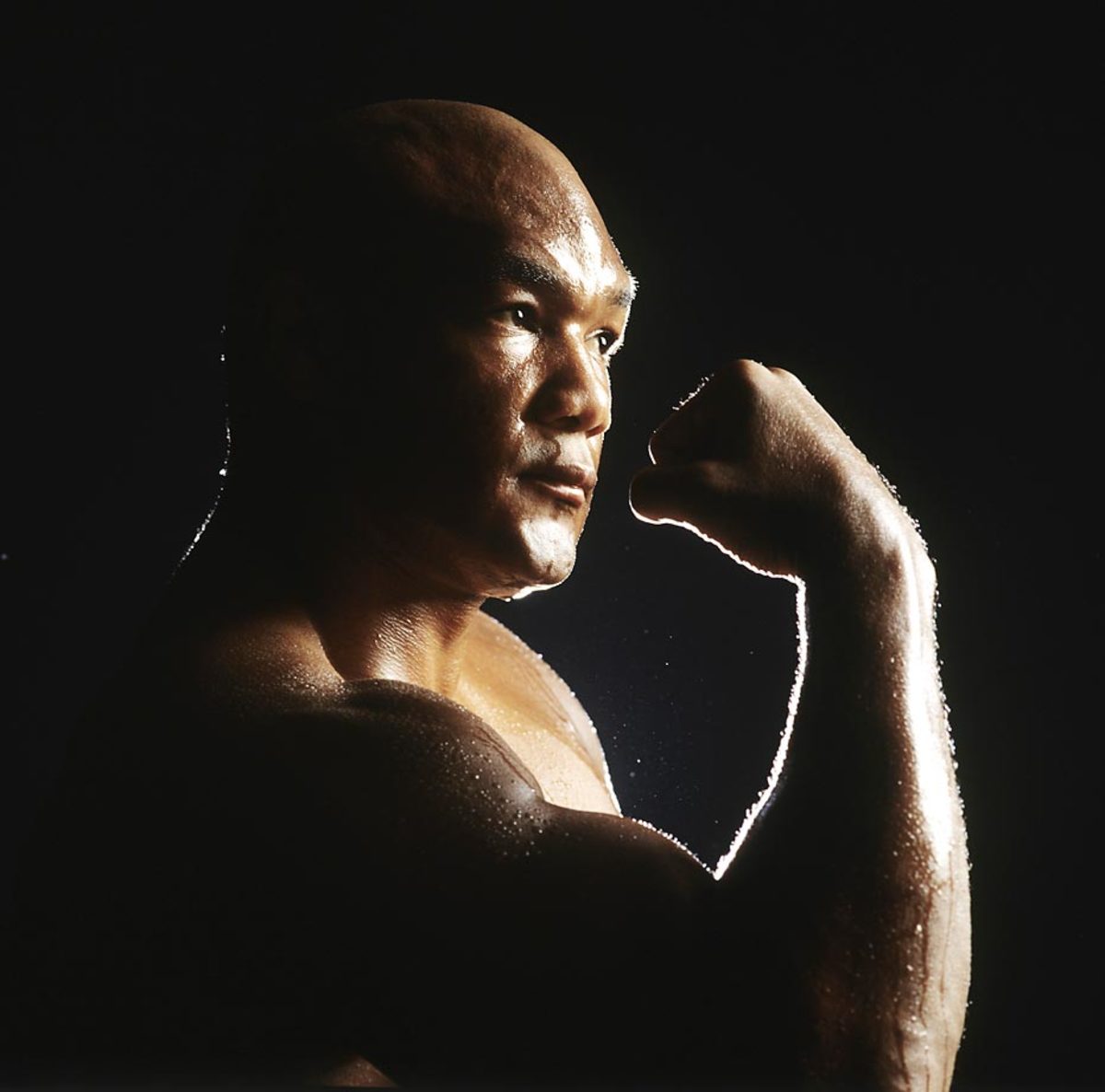

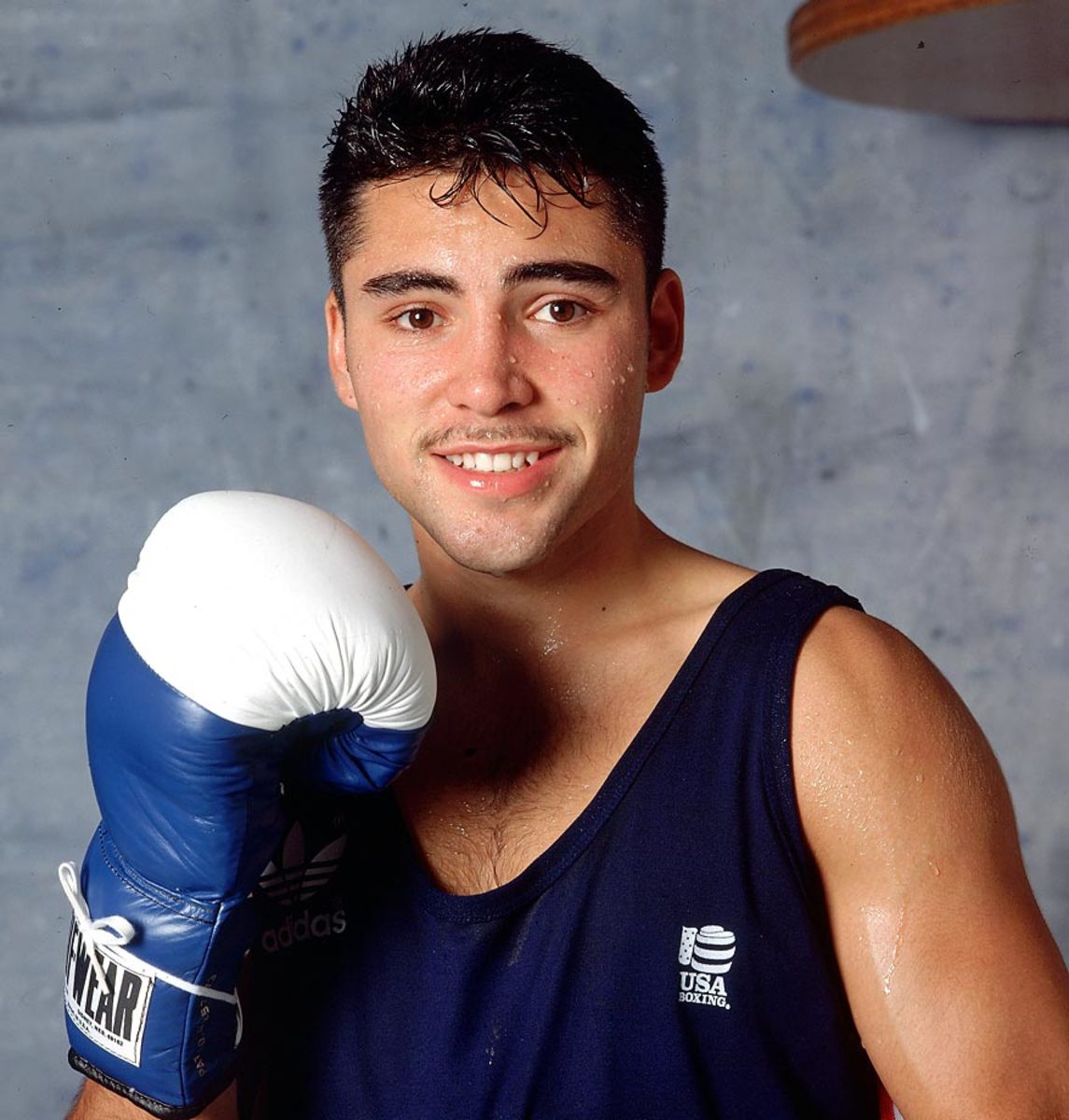

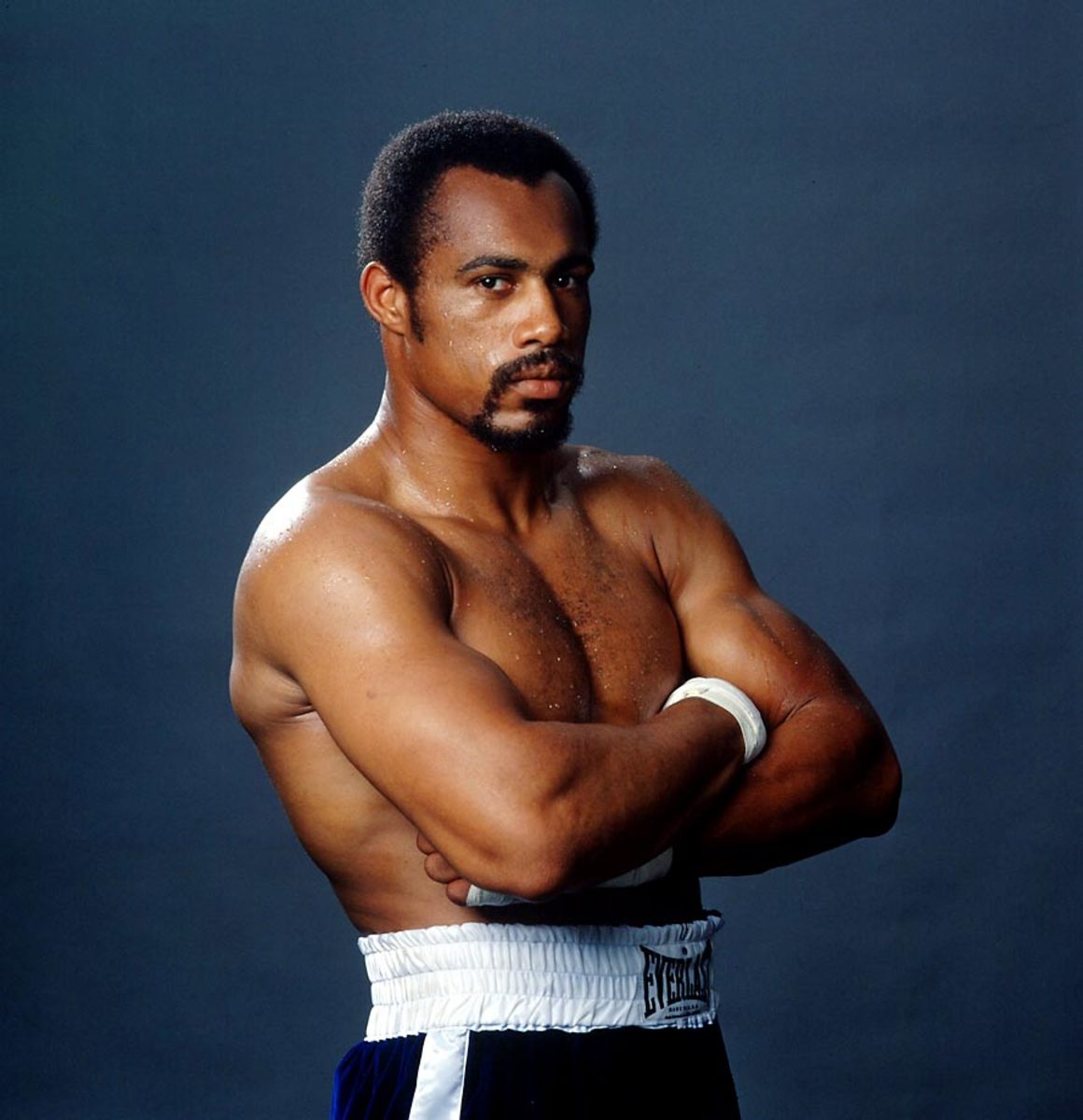

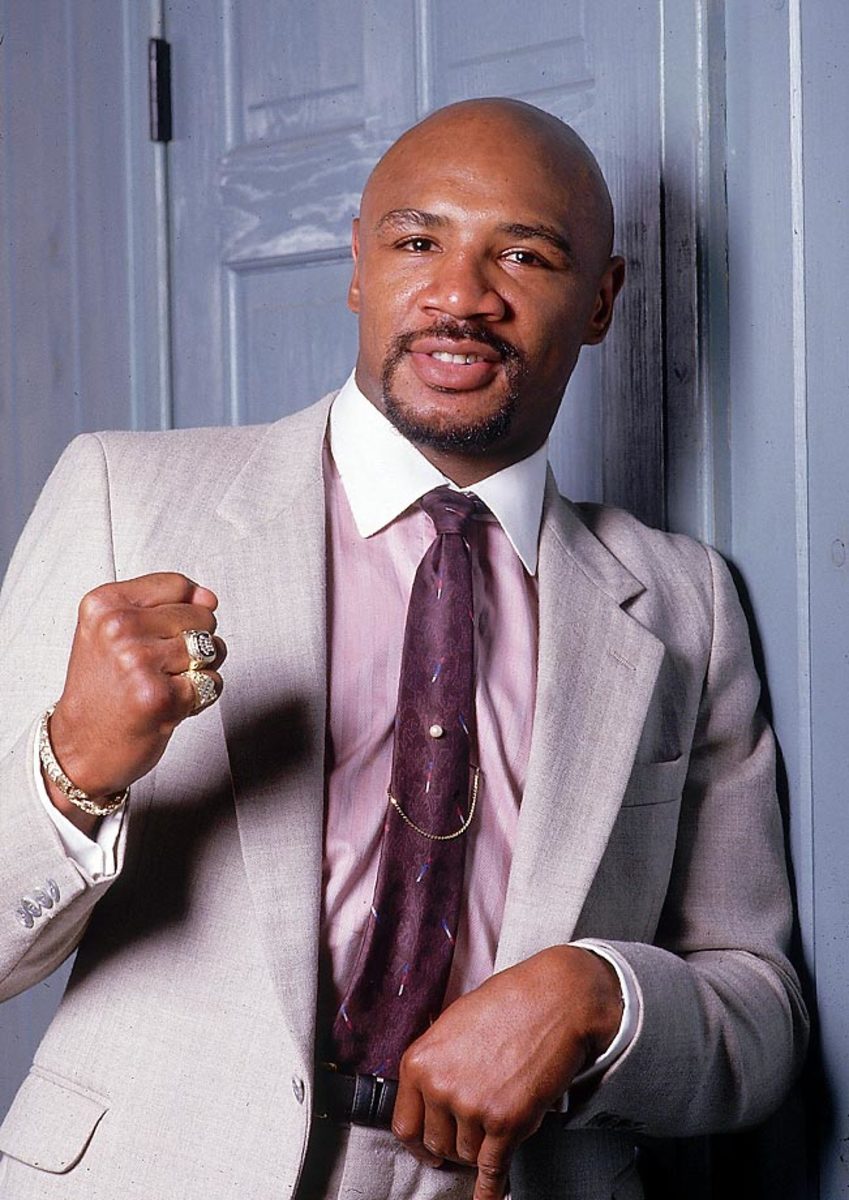

GALLERY: SI'S BEST BOXING PORTRAITS

Best Boxing Portraits

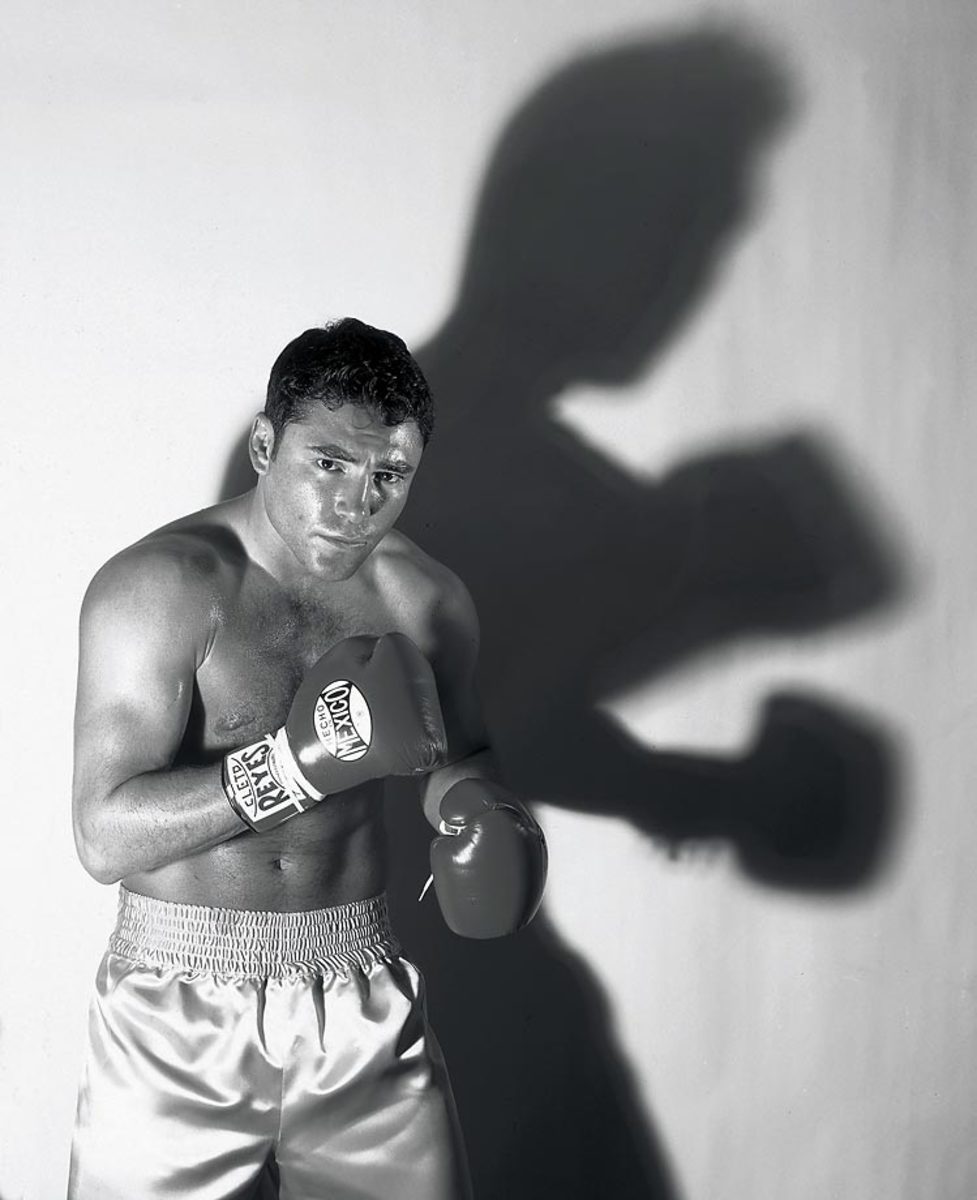

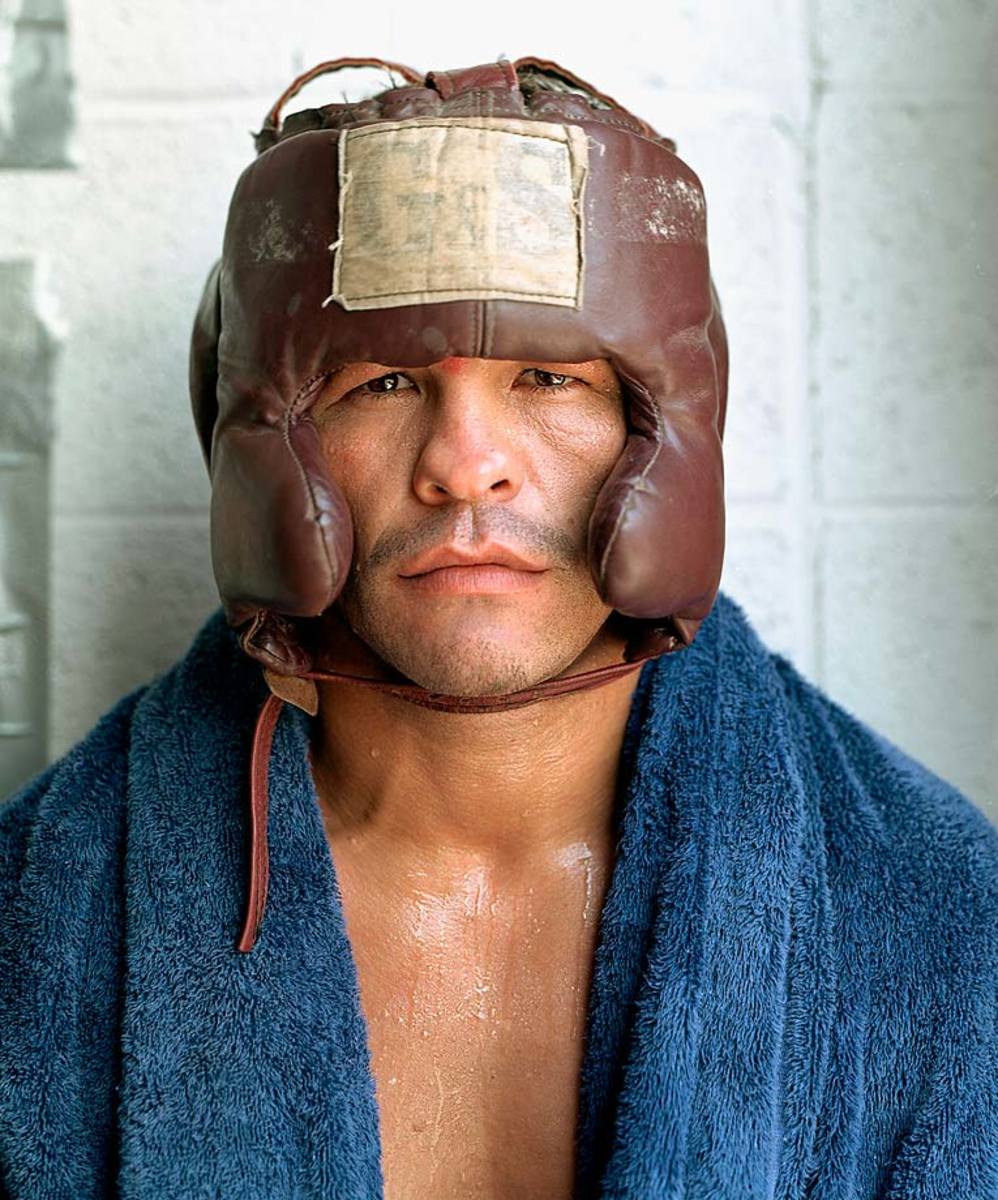

Oscar De La Hoya, 1995

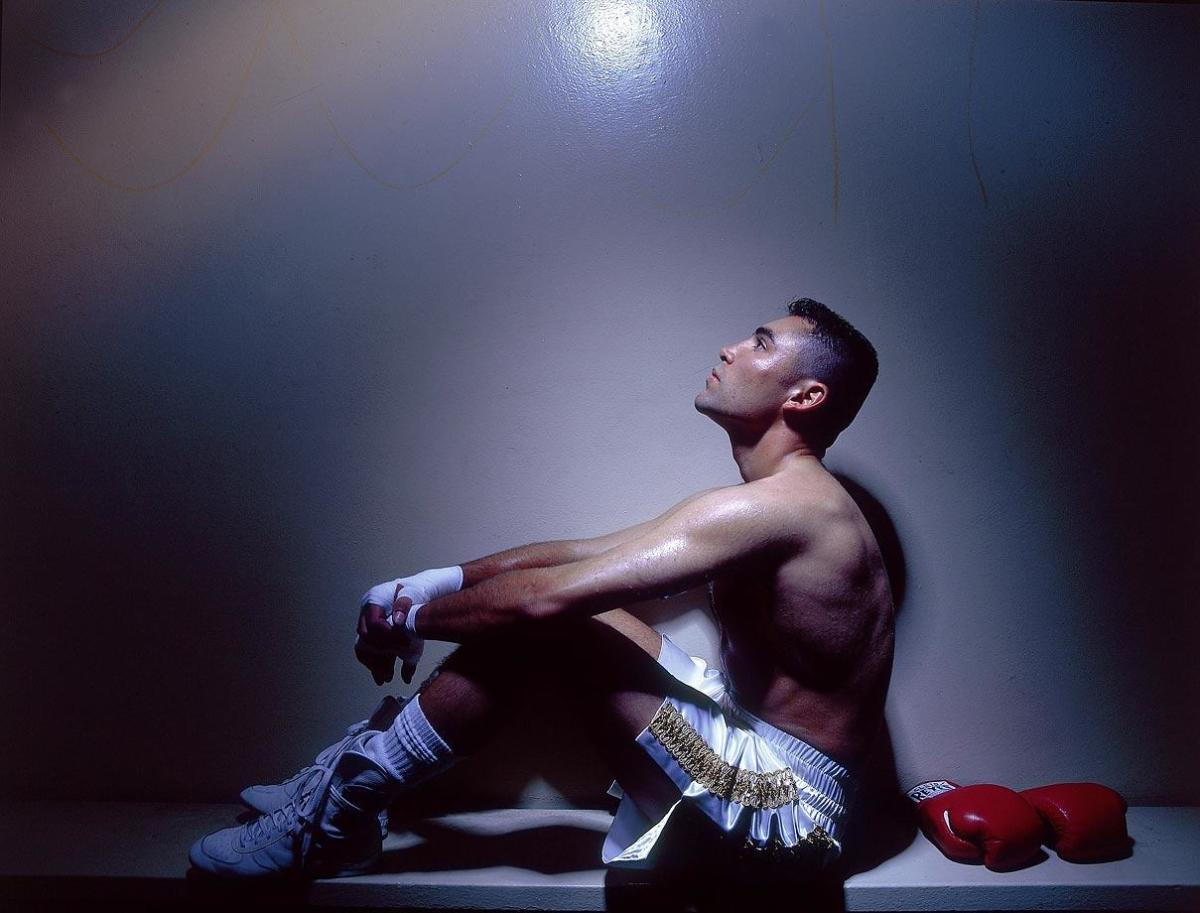

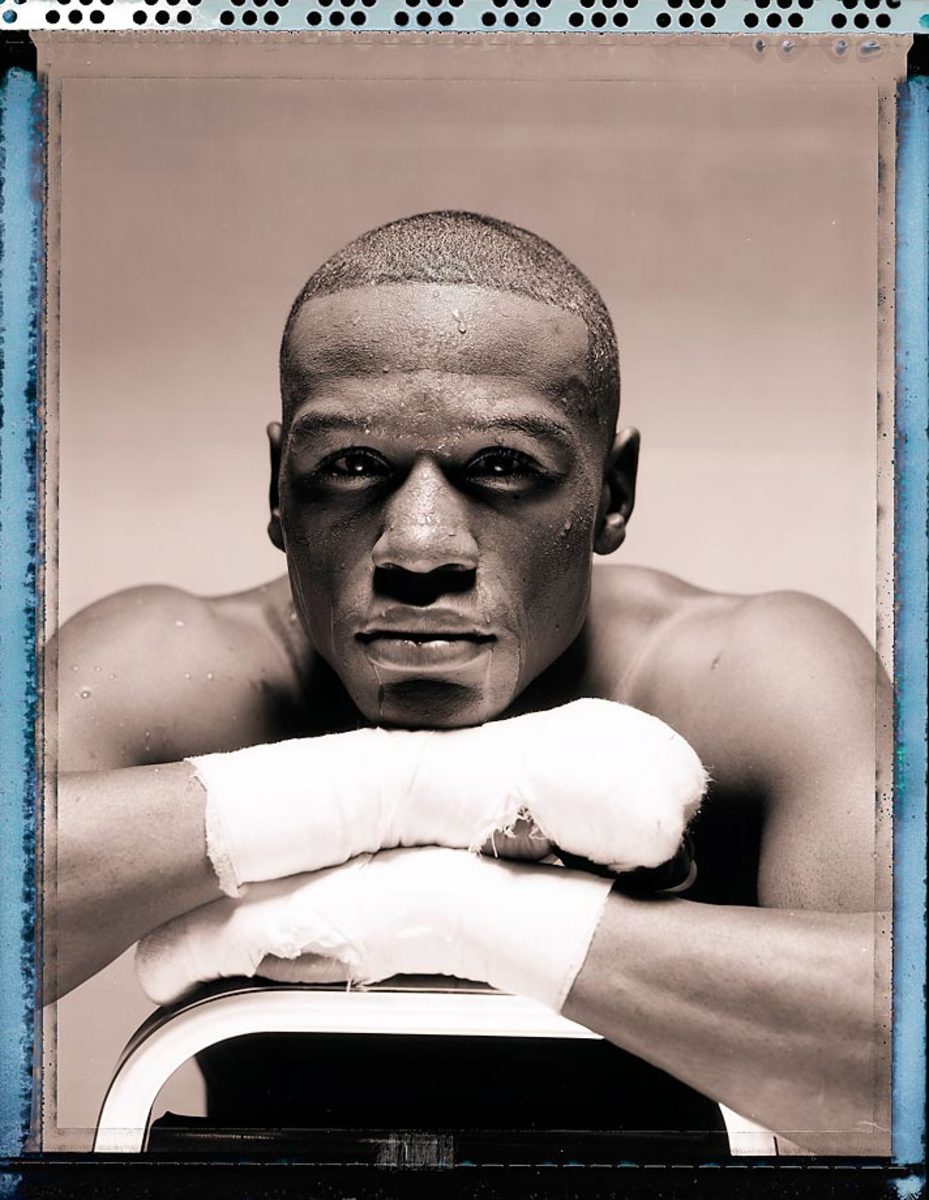

Floyd Mayweather Jr., 2005

Wladmir and Vitali Klitschko, 2002

Manny Pacquiao, 2011

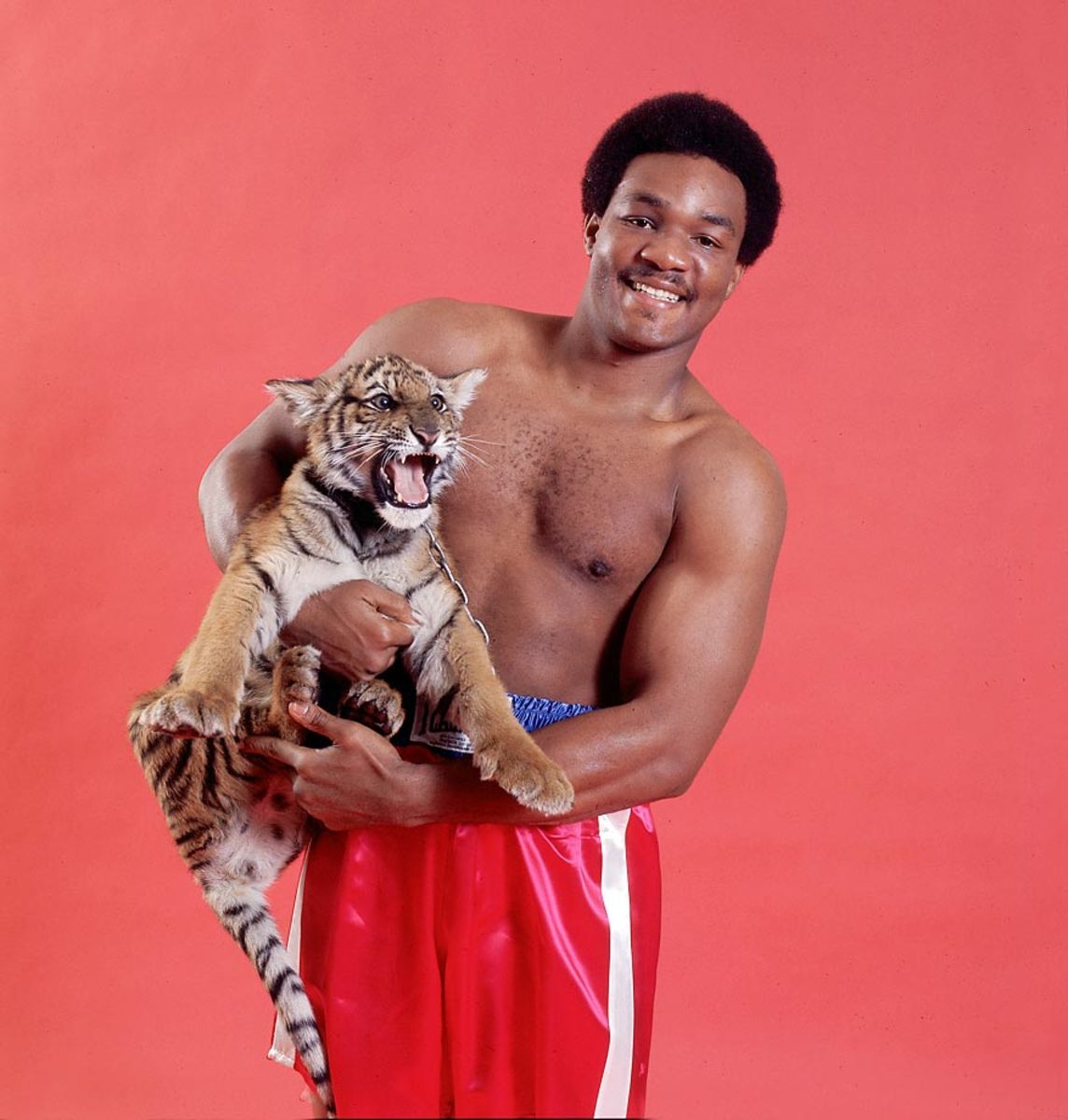

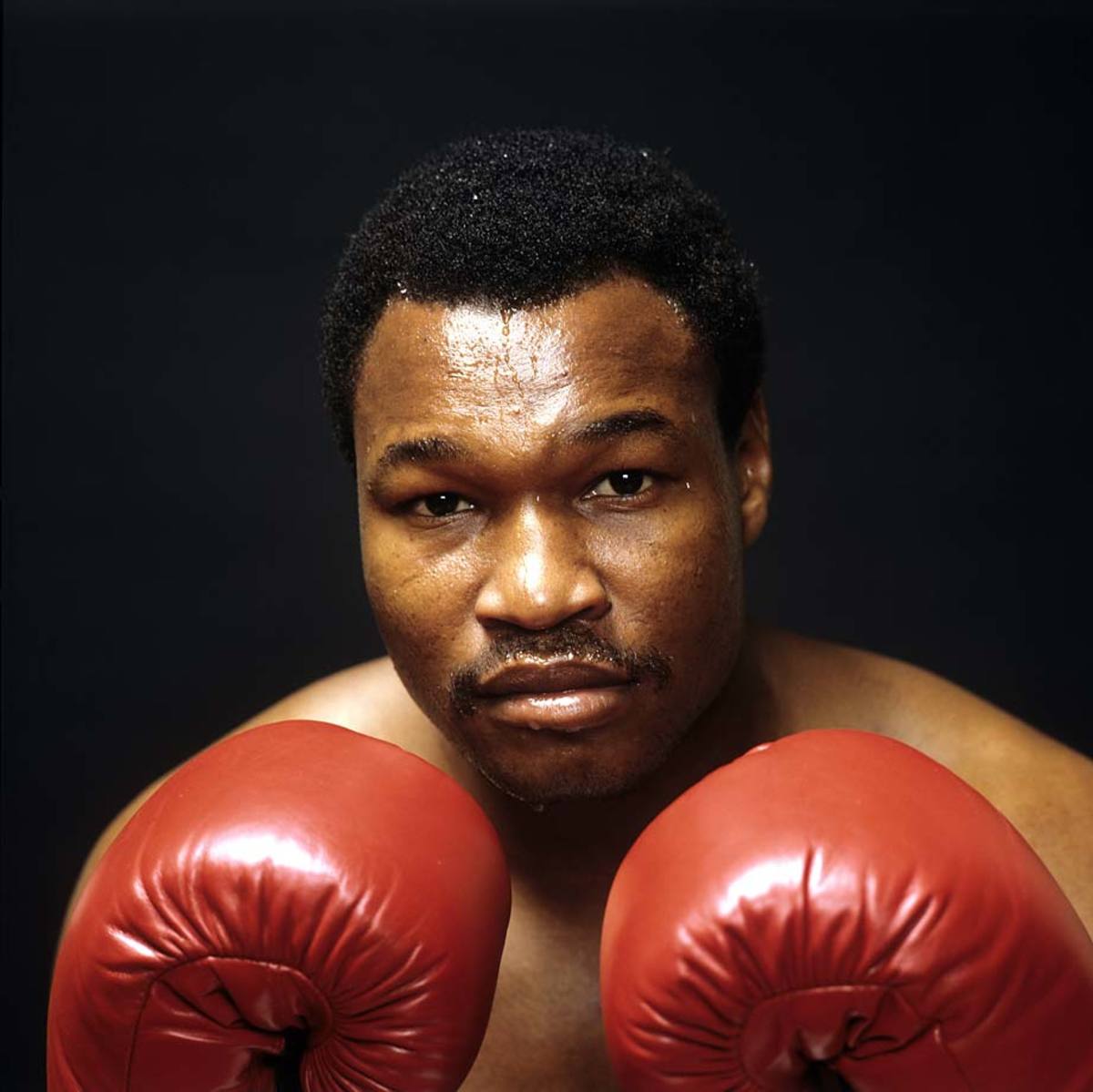

George Foreman, 1975

Bernard Hopkins, 1999

Lennox Lewis, 1998

Rocky Marciano, 1953

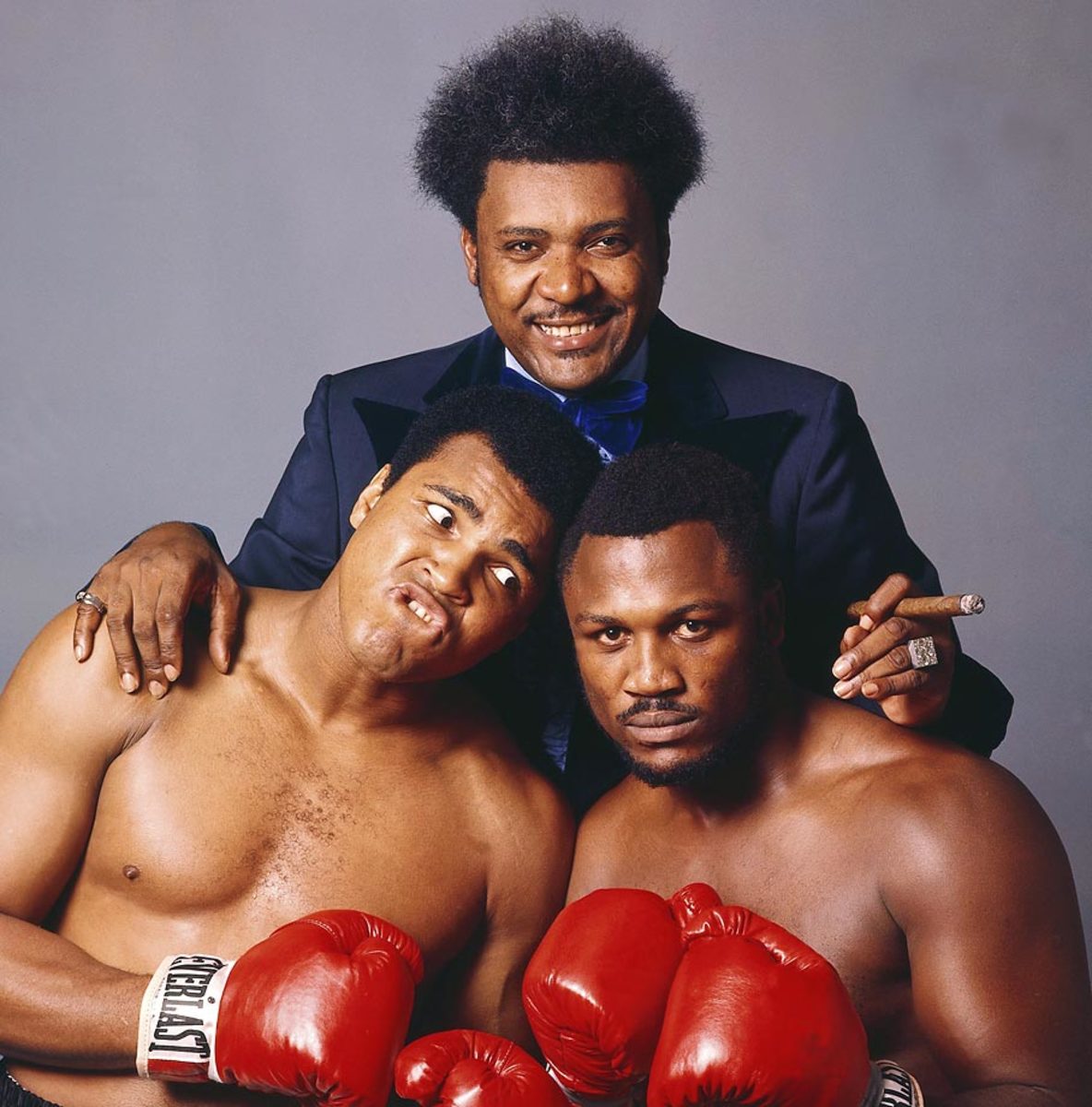

Muhammad Ali, Don King, Joe Frazier, 1975

Sonny Liston, 1967

Tommy Hearns, 2000

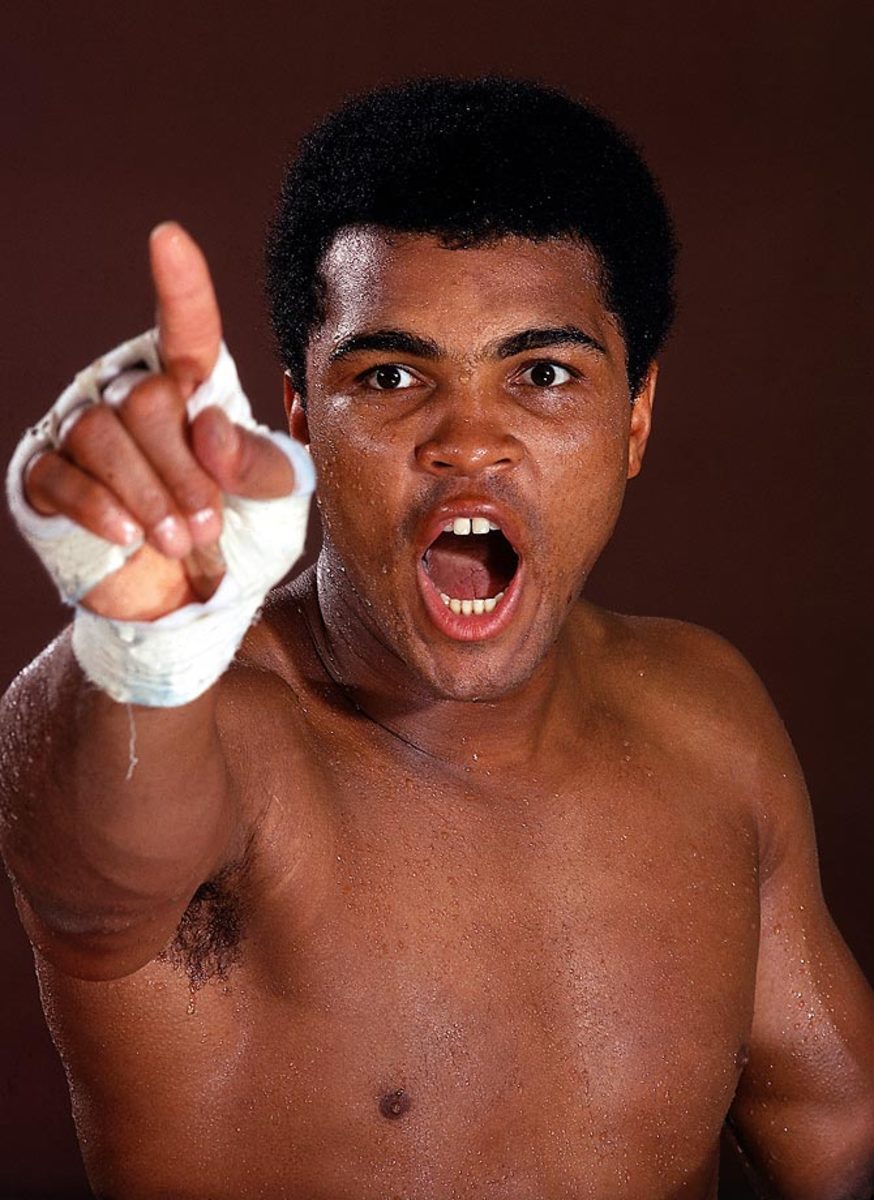

Muhammad Ali, 1970

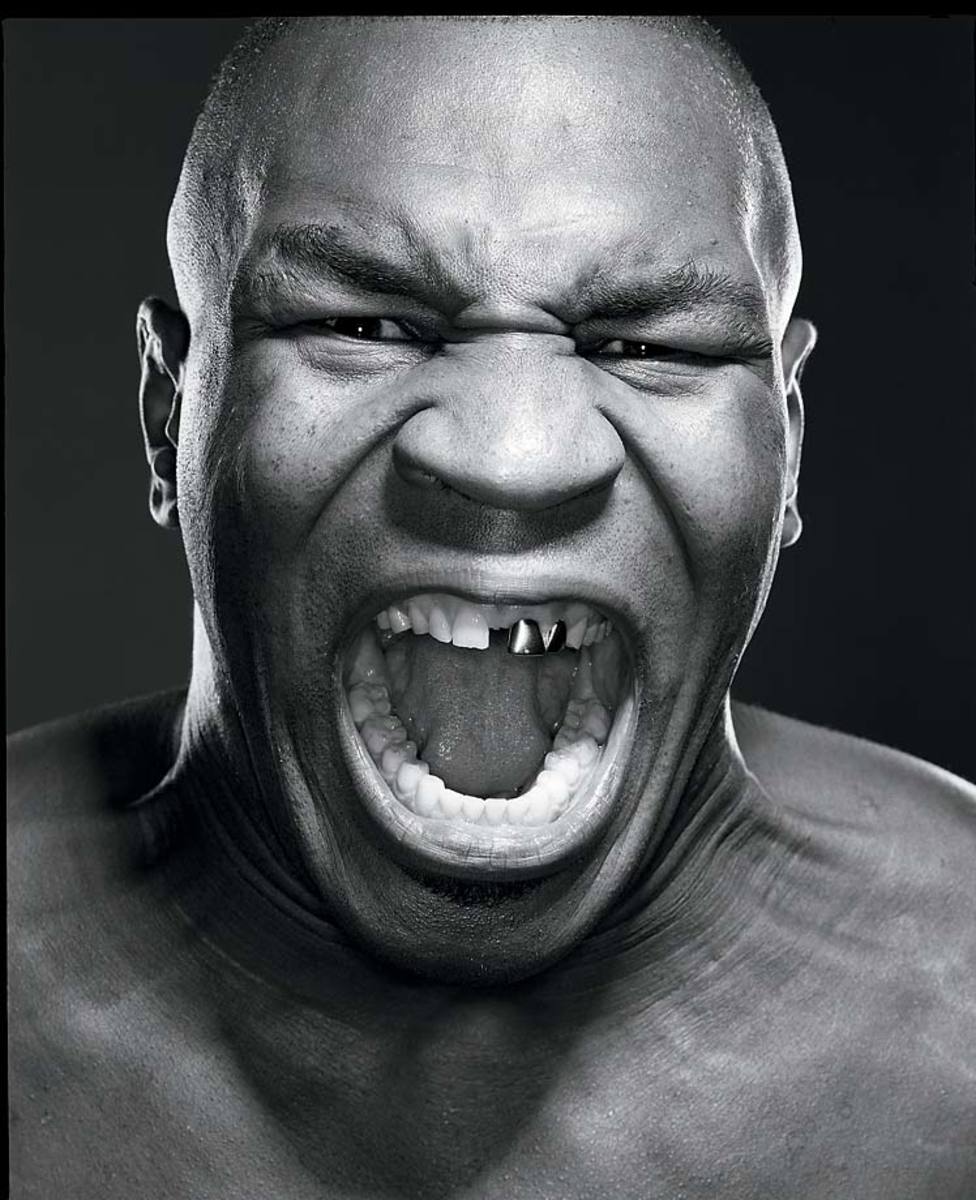

Mike Tyson, 2002

George Foreman, 1991

Oscar De La Hoya, 1992

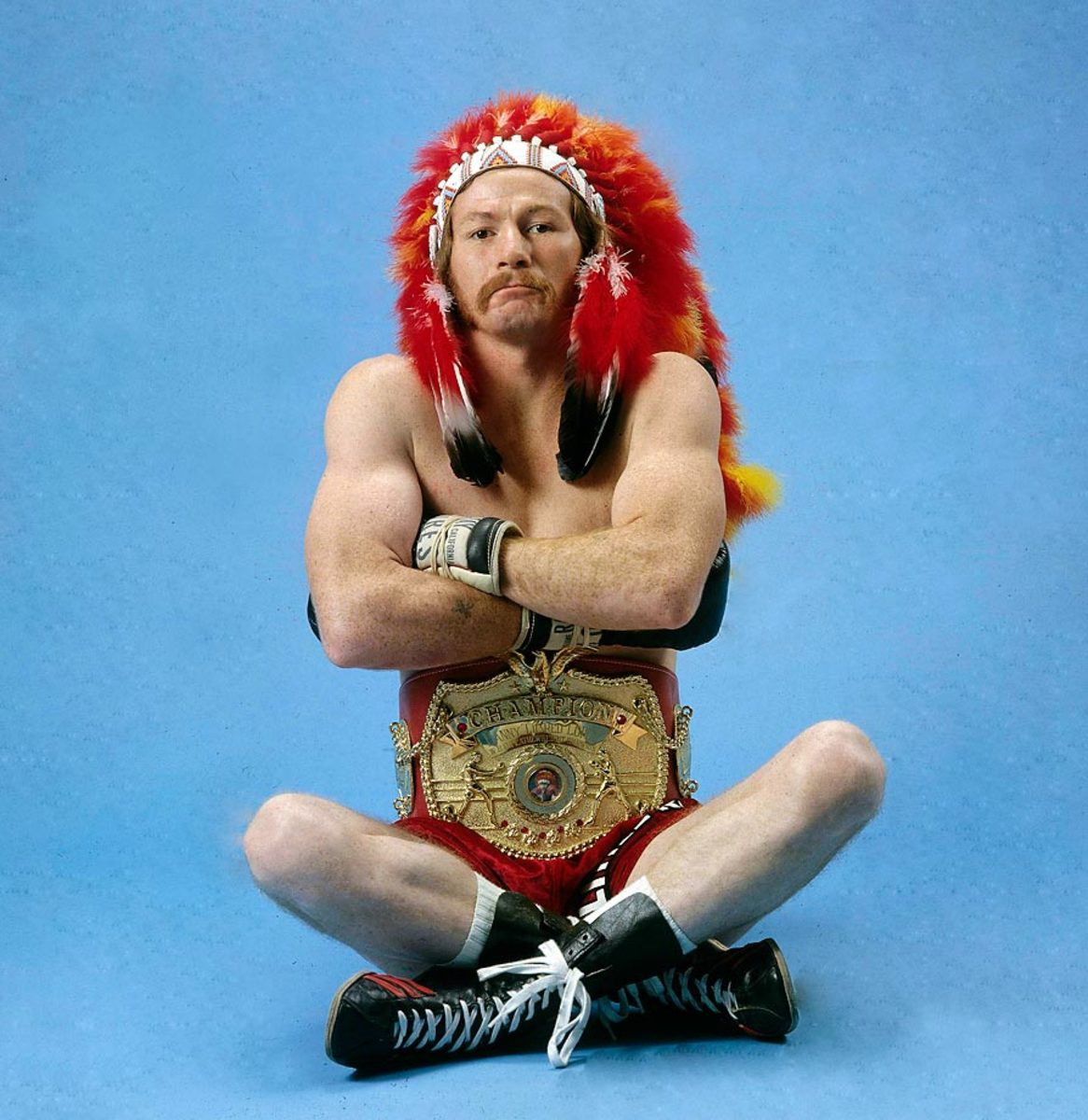

Gerry Cooney, 1982

Ken Norton, 1976

Marvin Hagler, 1987

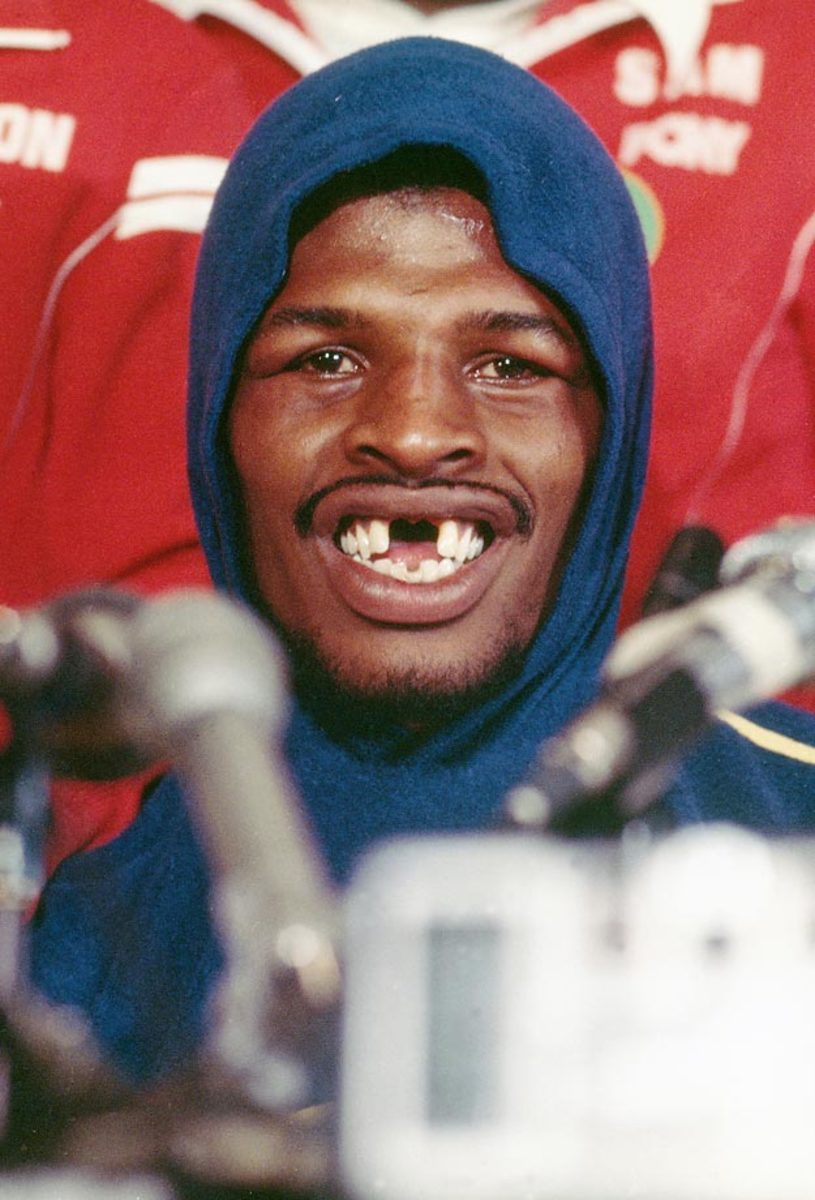

Leon Spinks, 1978

Tommy Hearns, 1980

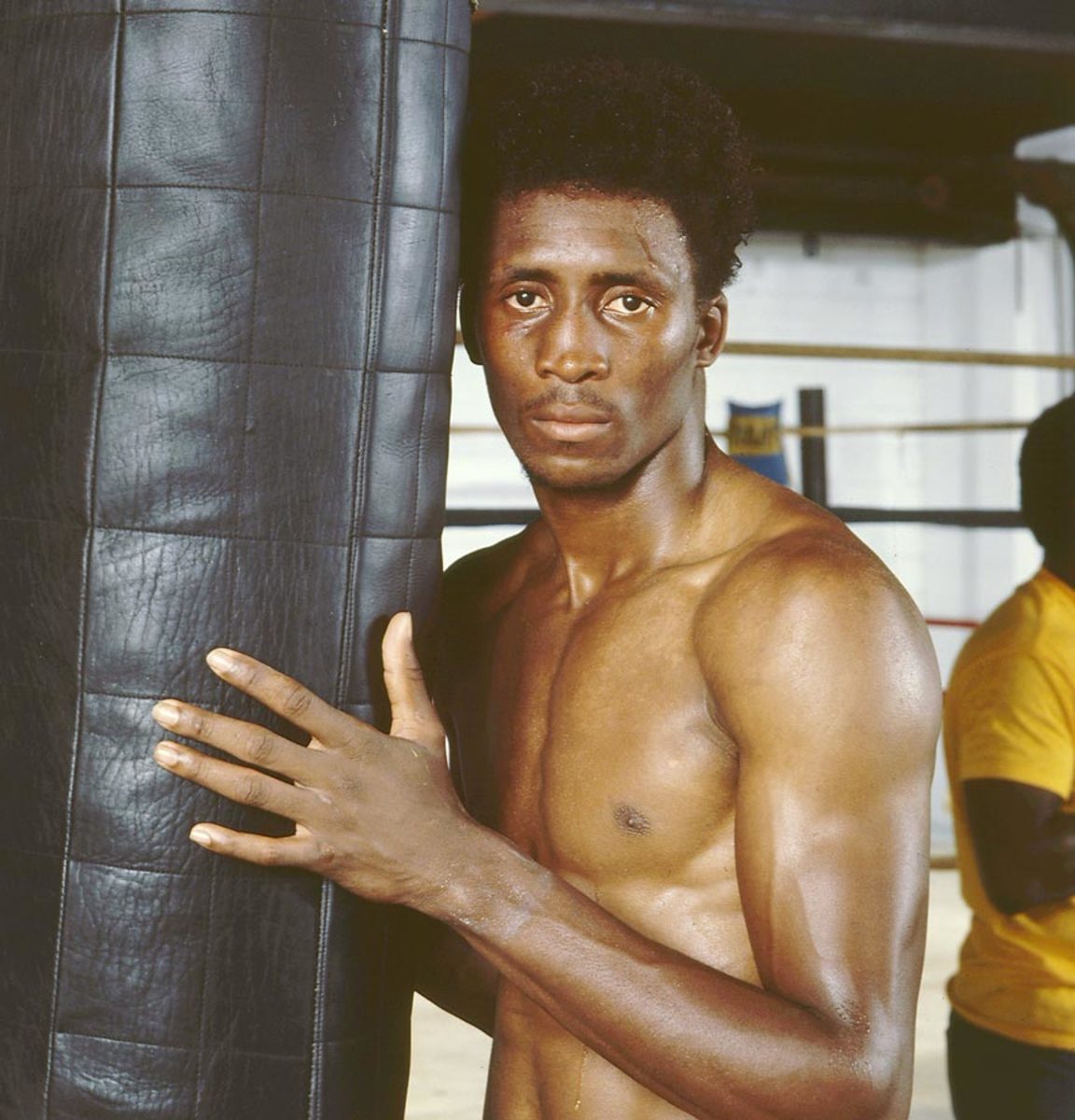

Danny Lopez, 1979

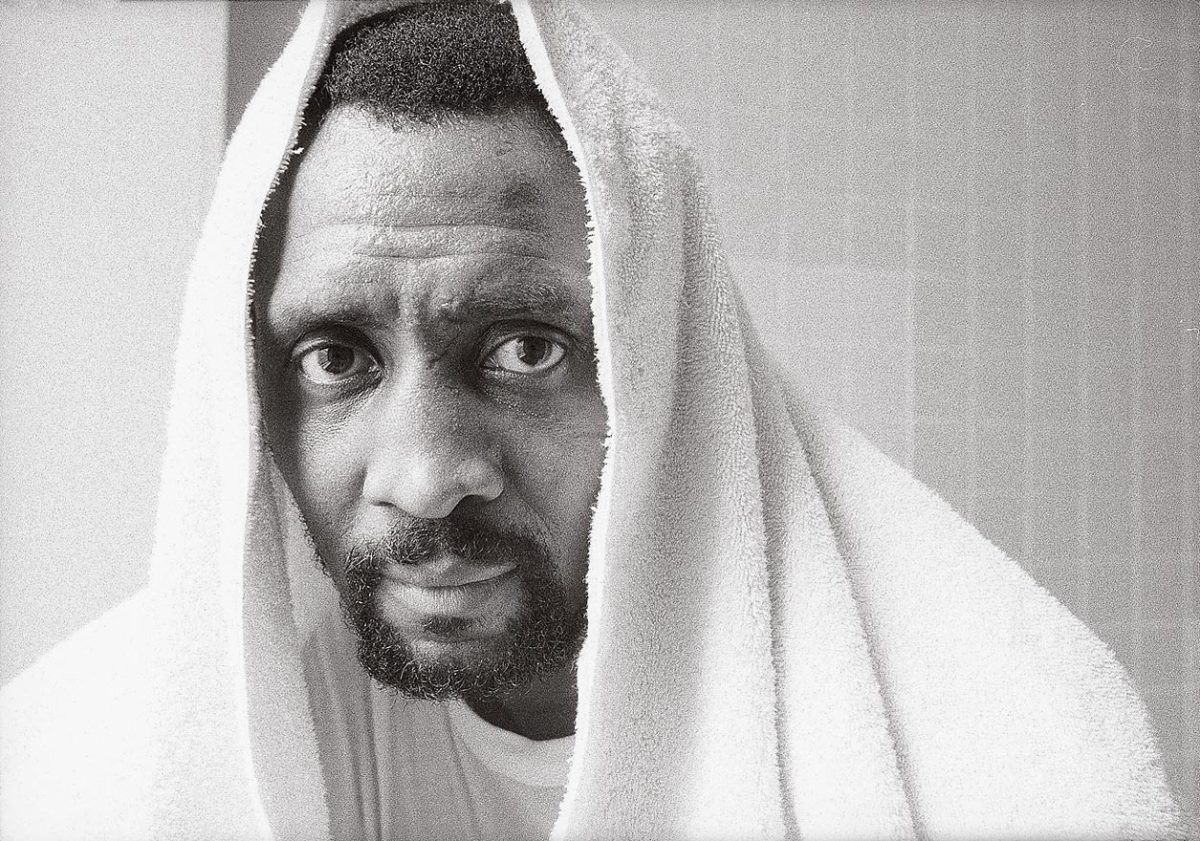

Joe Frazier, 1996

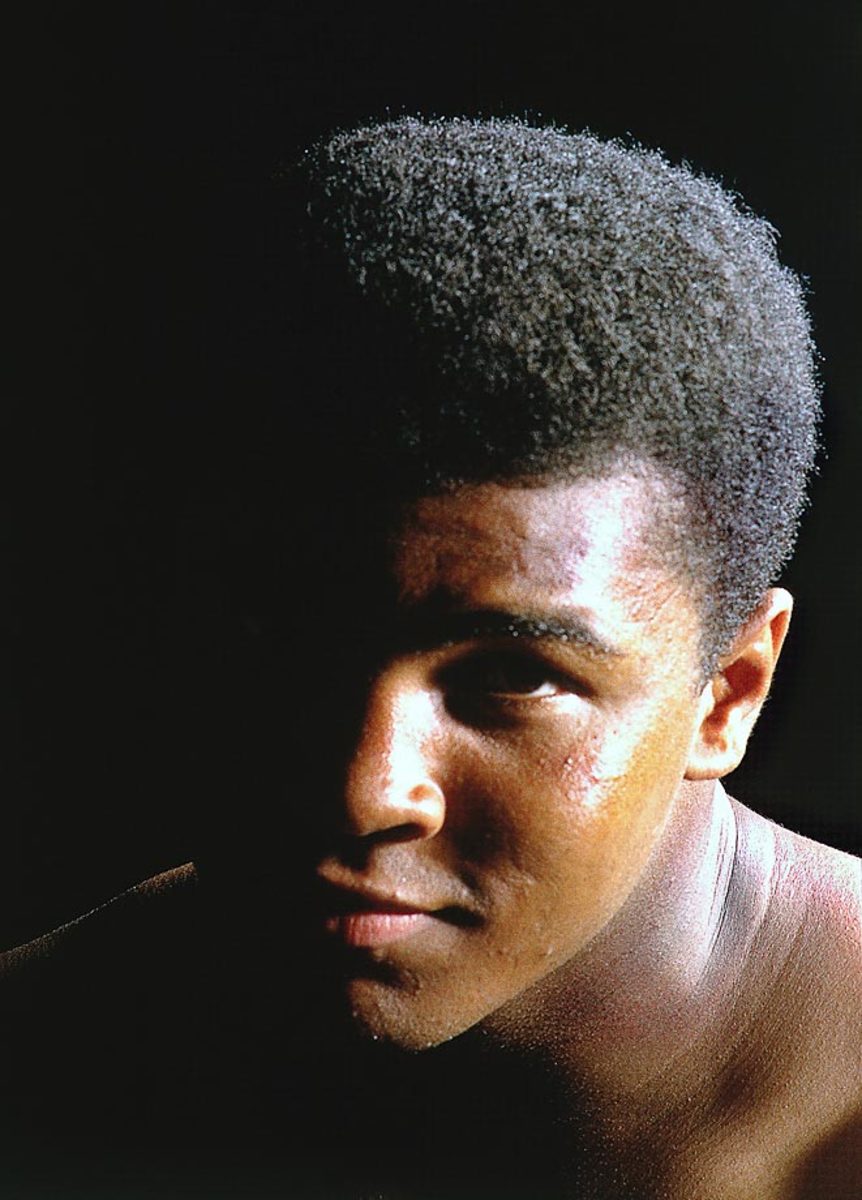

Muhammad Ali, 1965

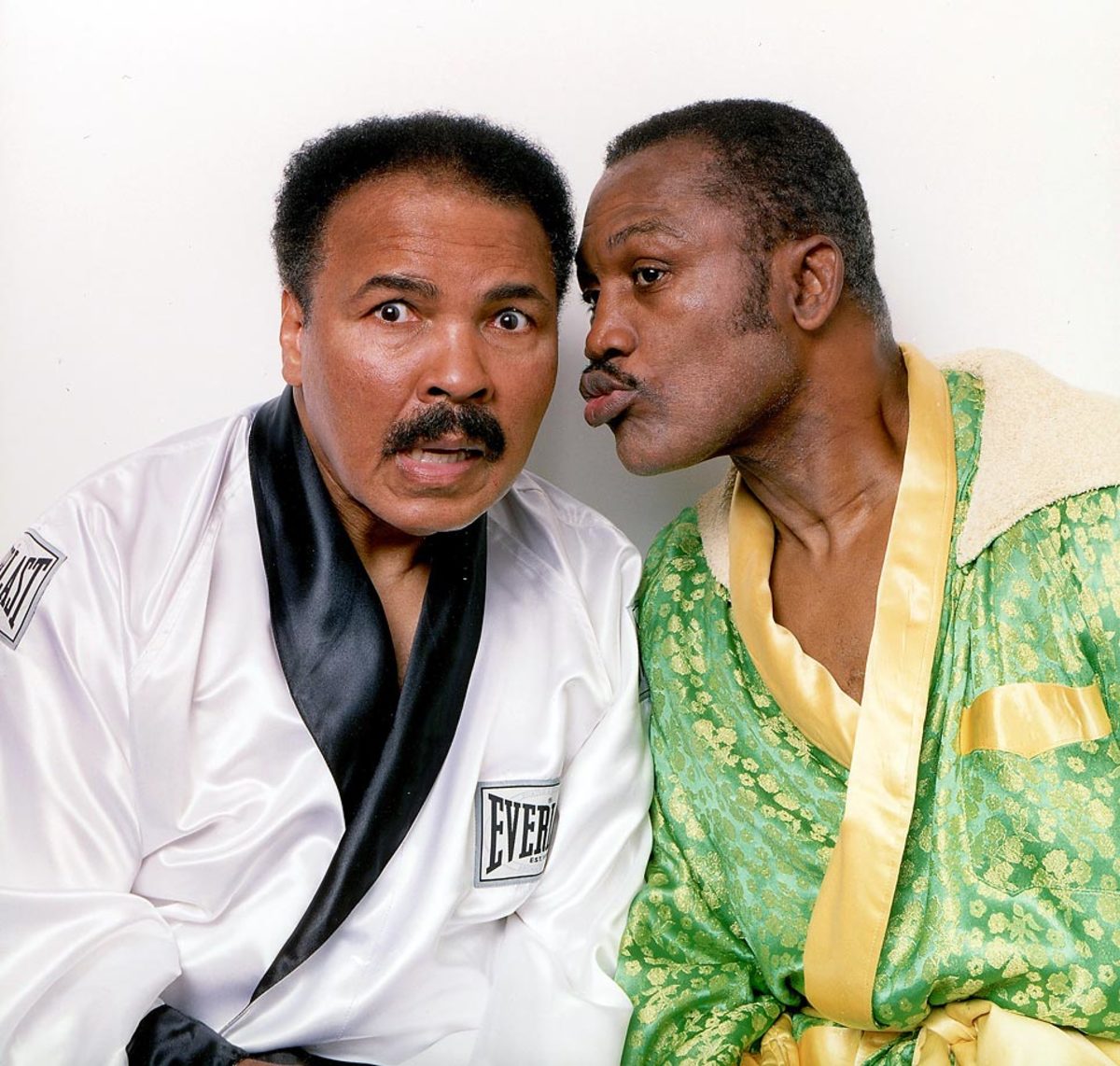

Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, 2003

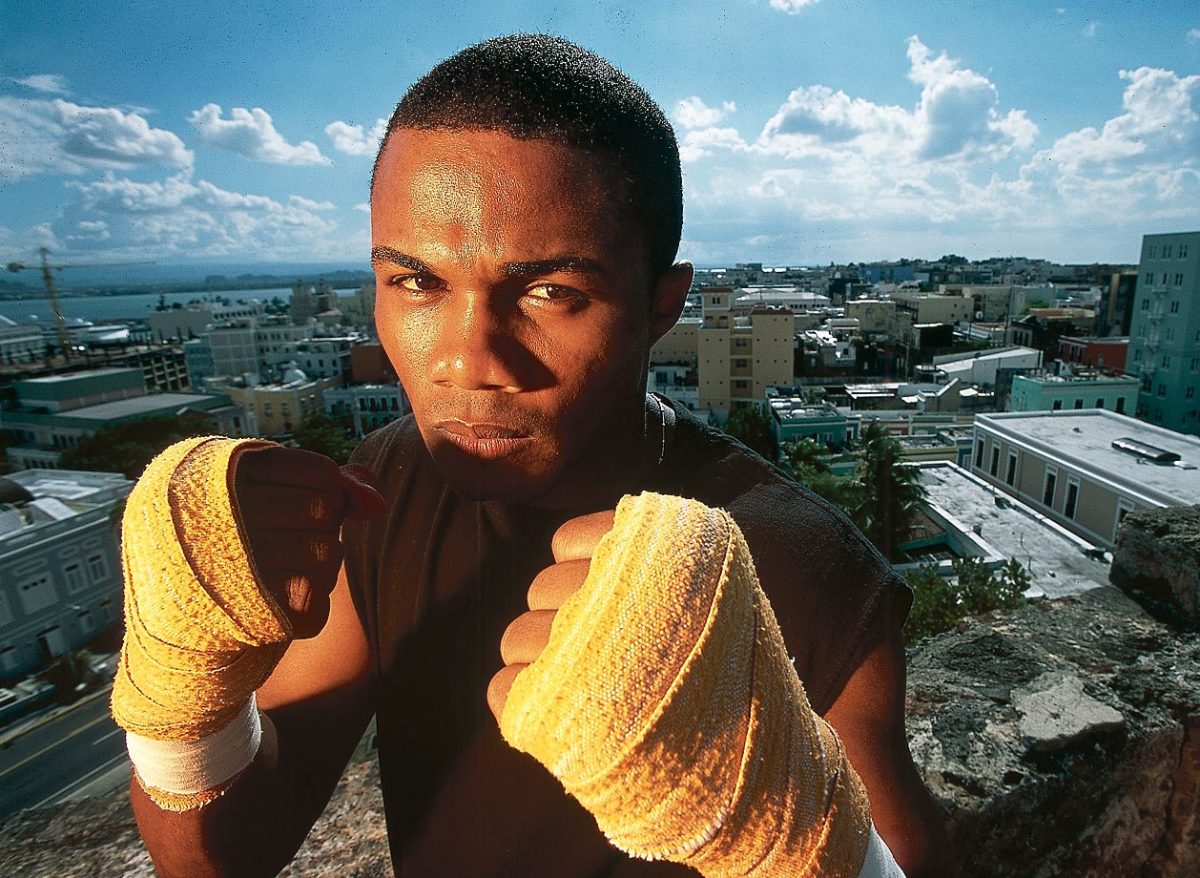

Felix Trinidad, 2001

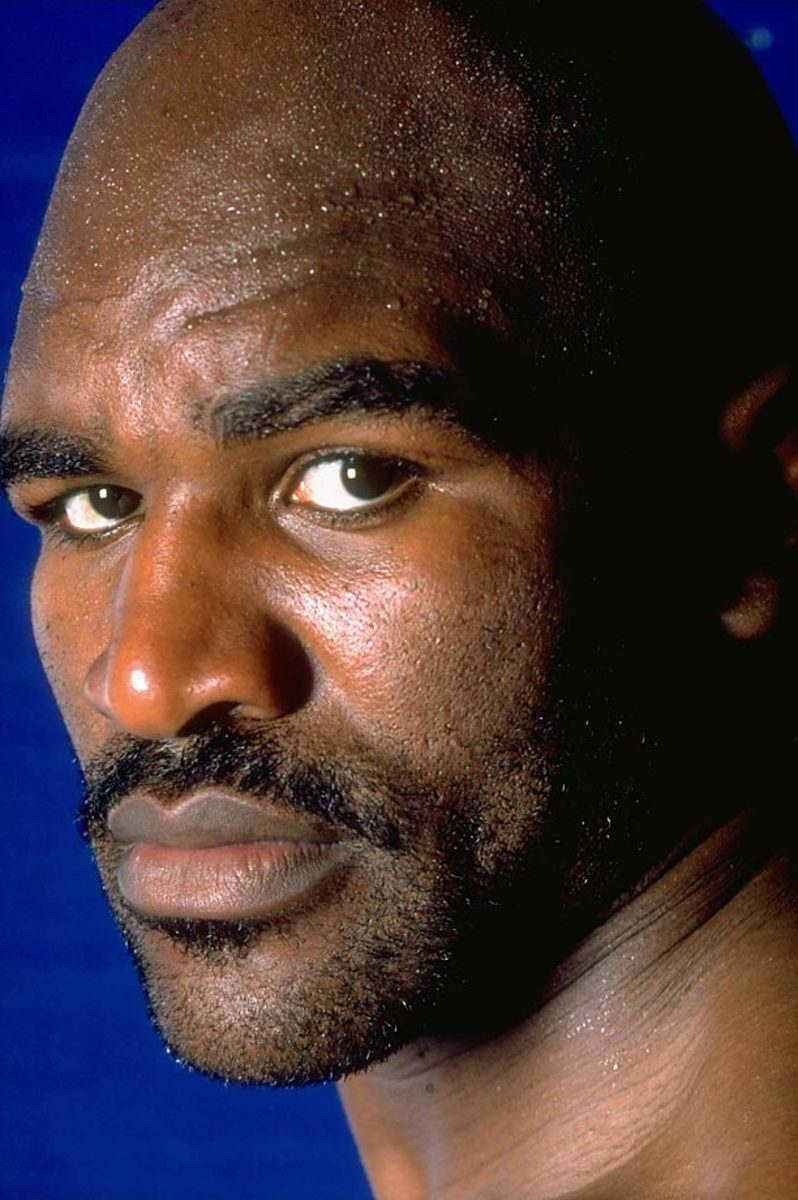

Evander Holyfield, 1997

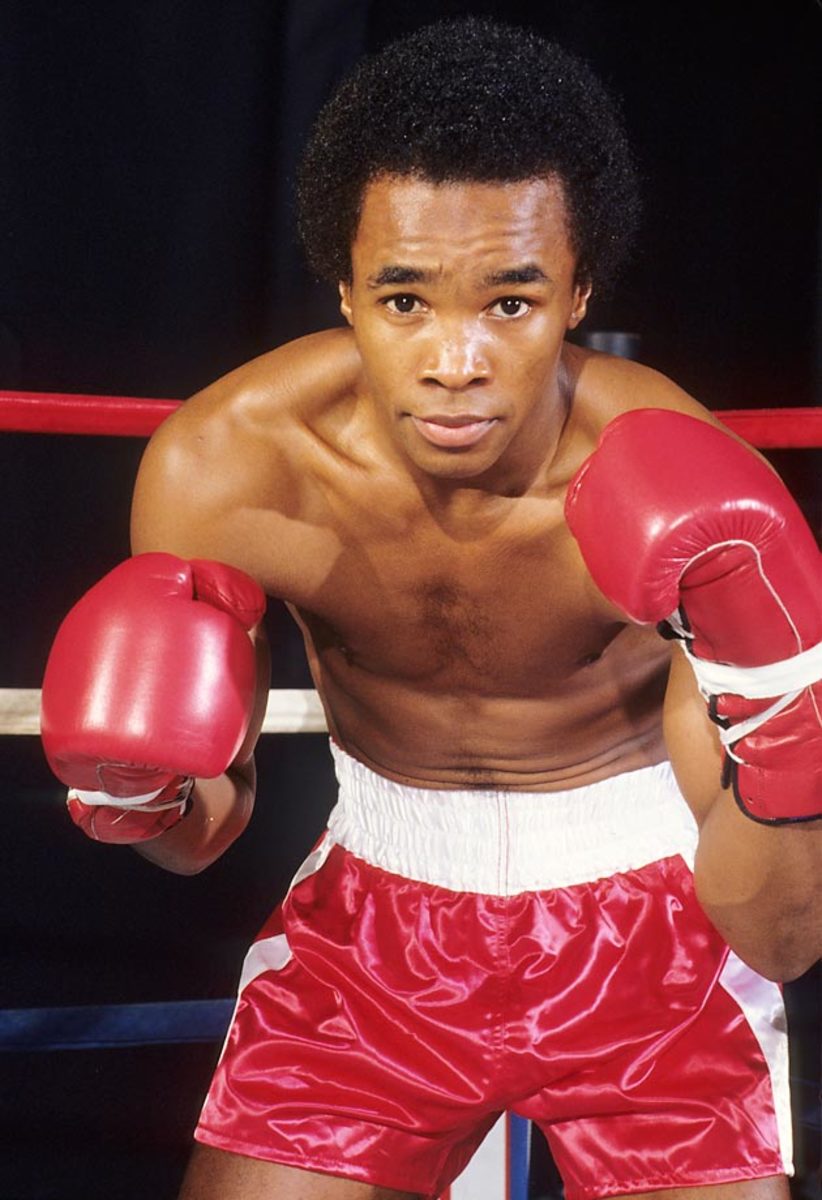

Sugar Ray Leonard, 1980

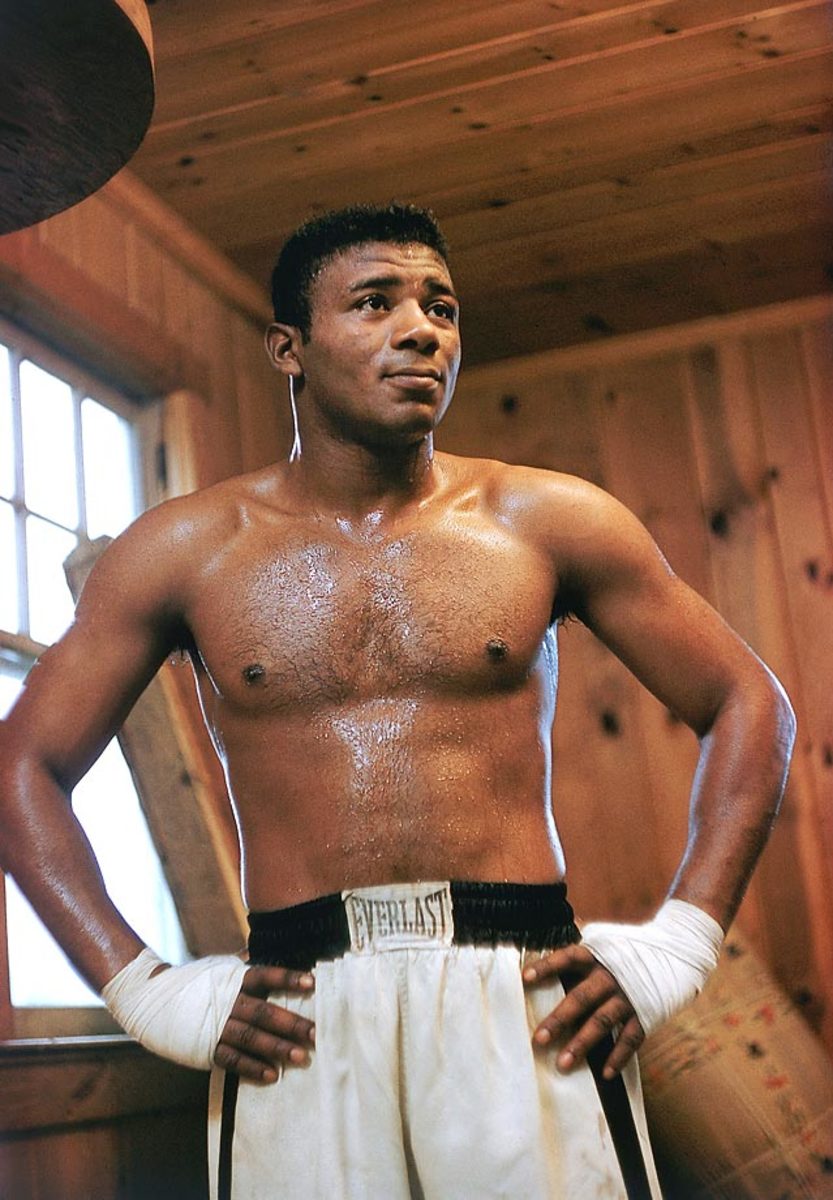

Floyd Patterson, 1956

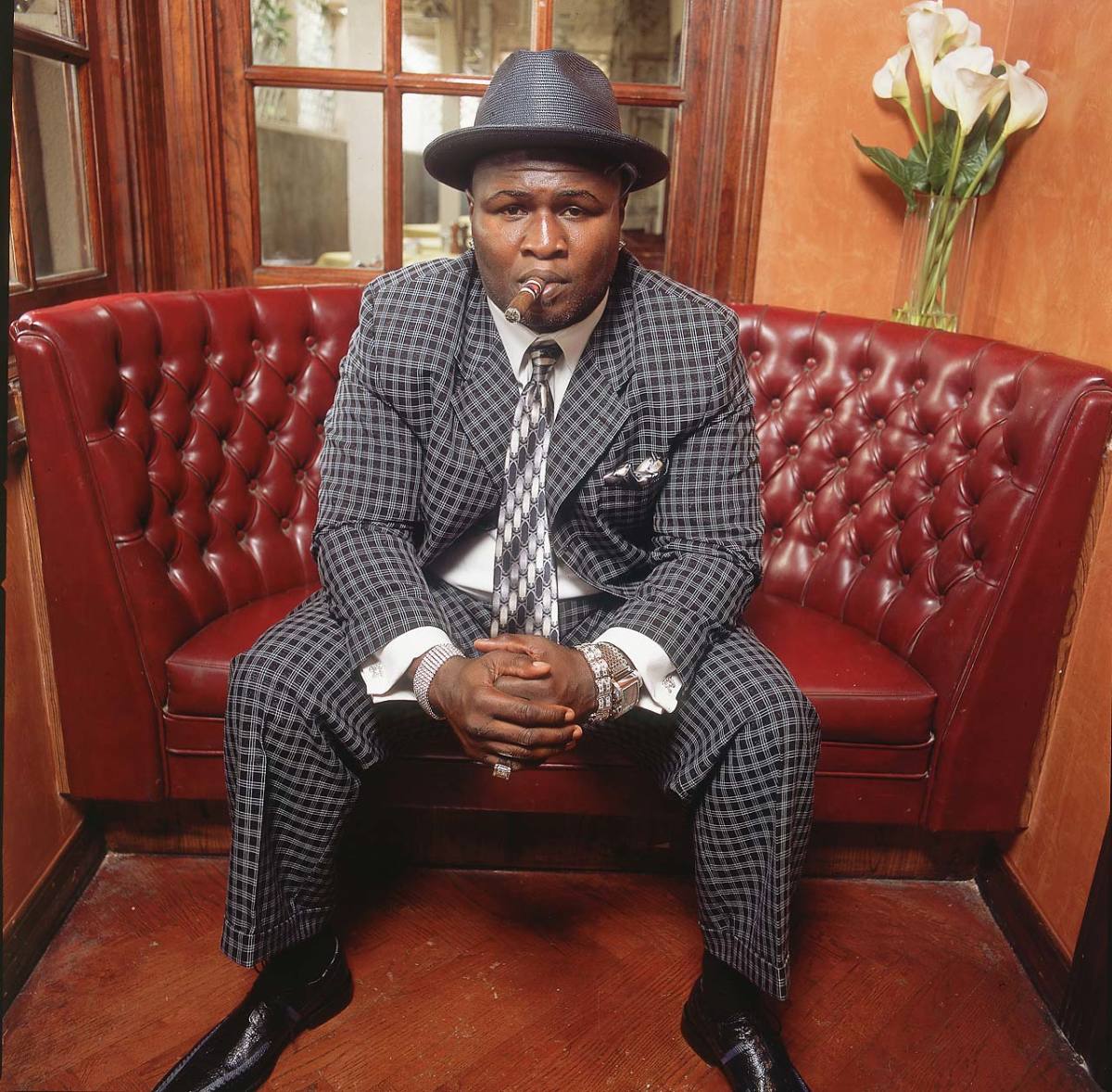

James Toney, 2006

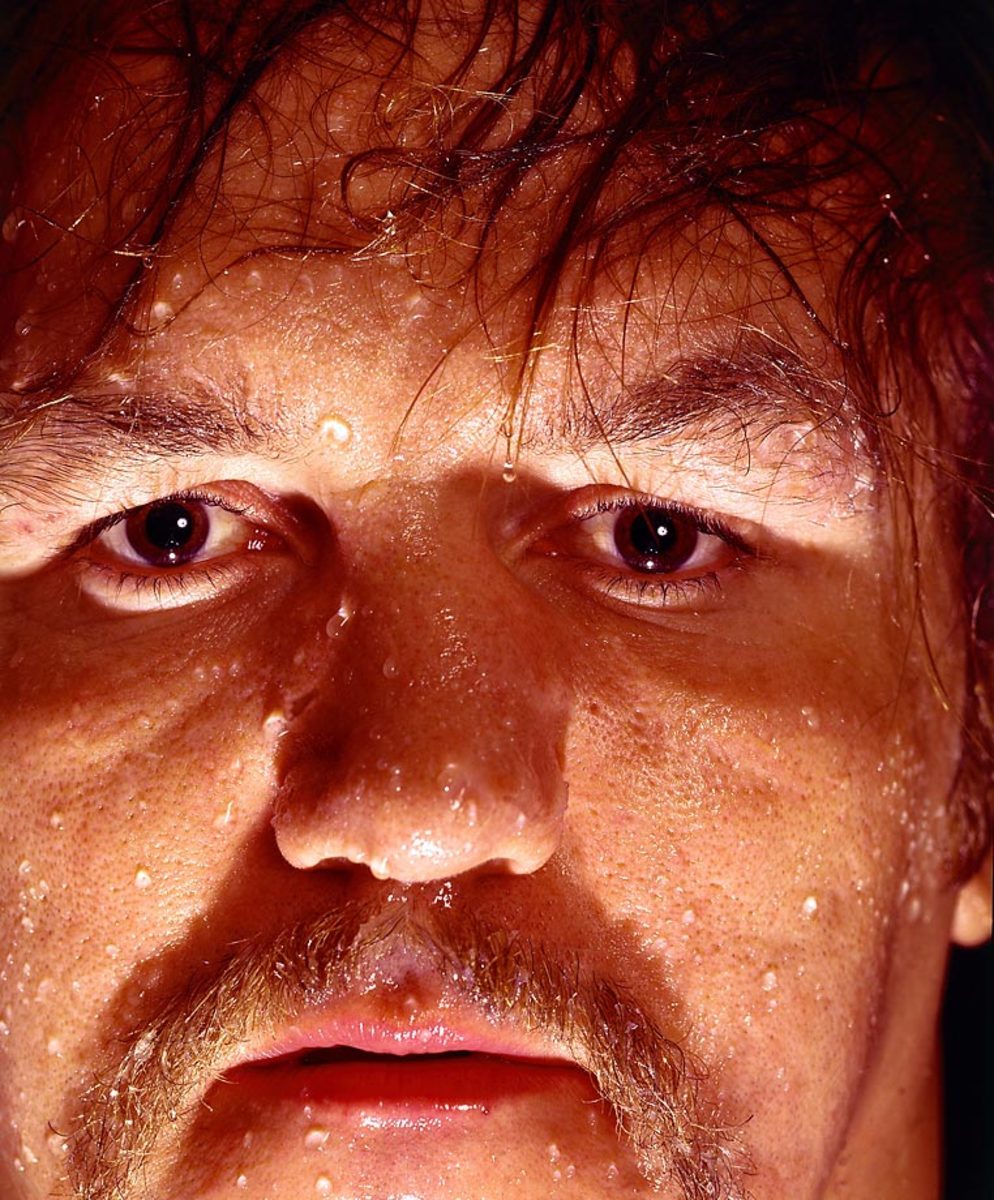

Chuck Wepner, 1975

Roy Jones, 2001

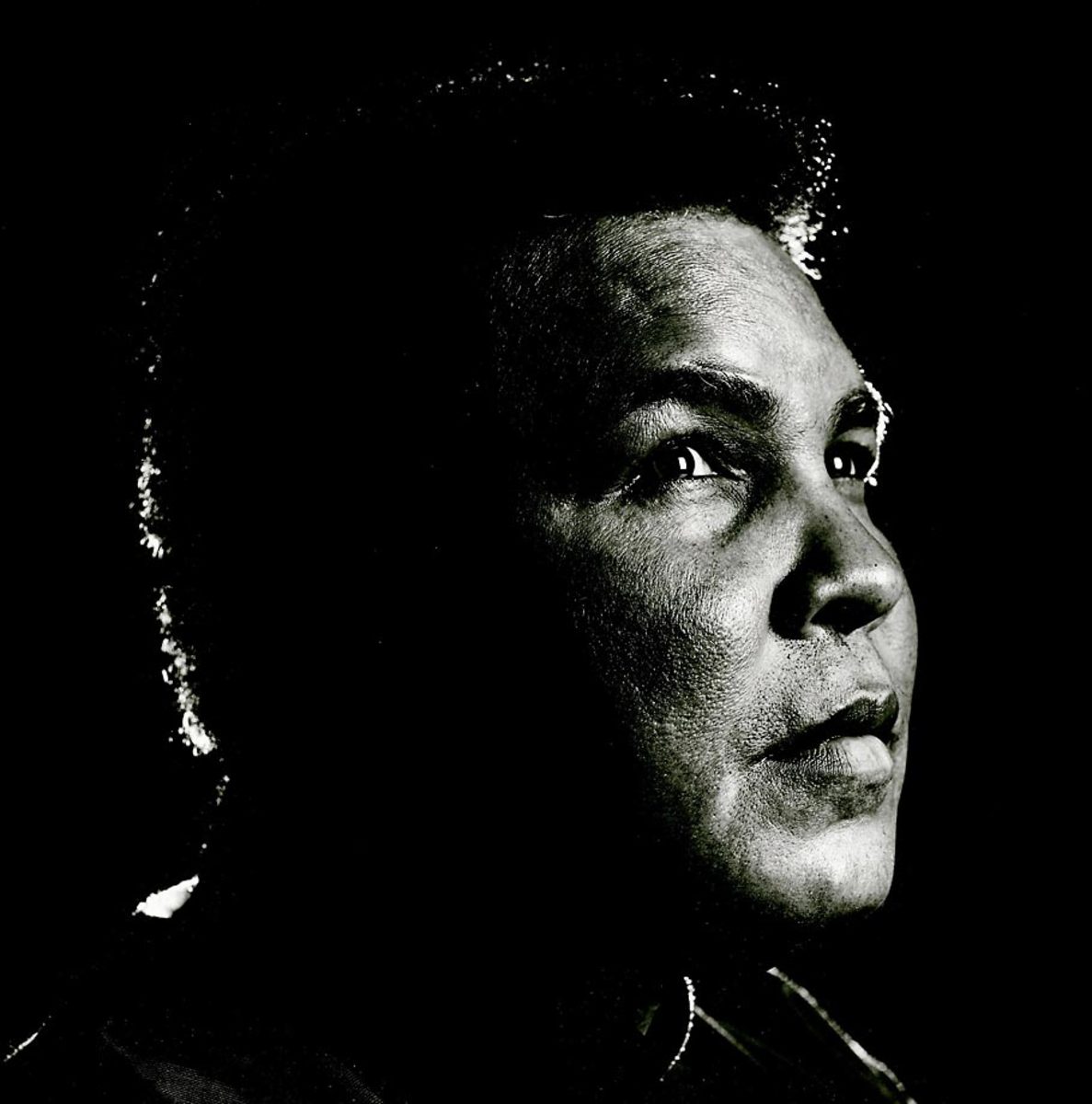

Muhammad Ali, 2006

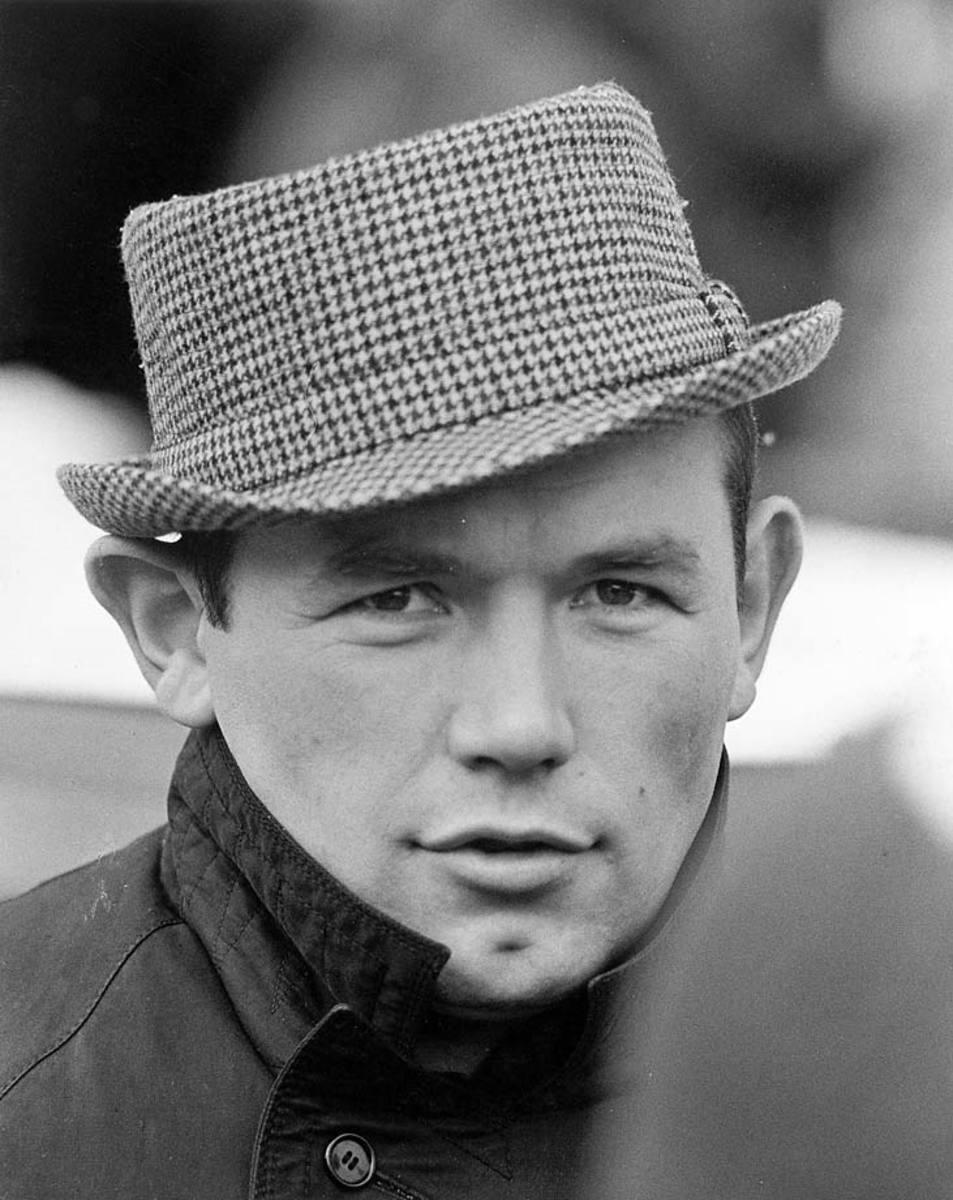

Ingmar Johansson, circa. 1960

Manny Pacquiao, 2008

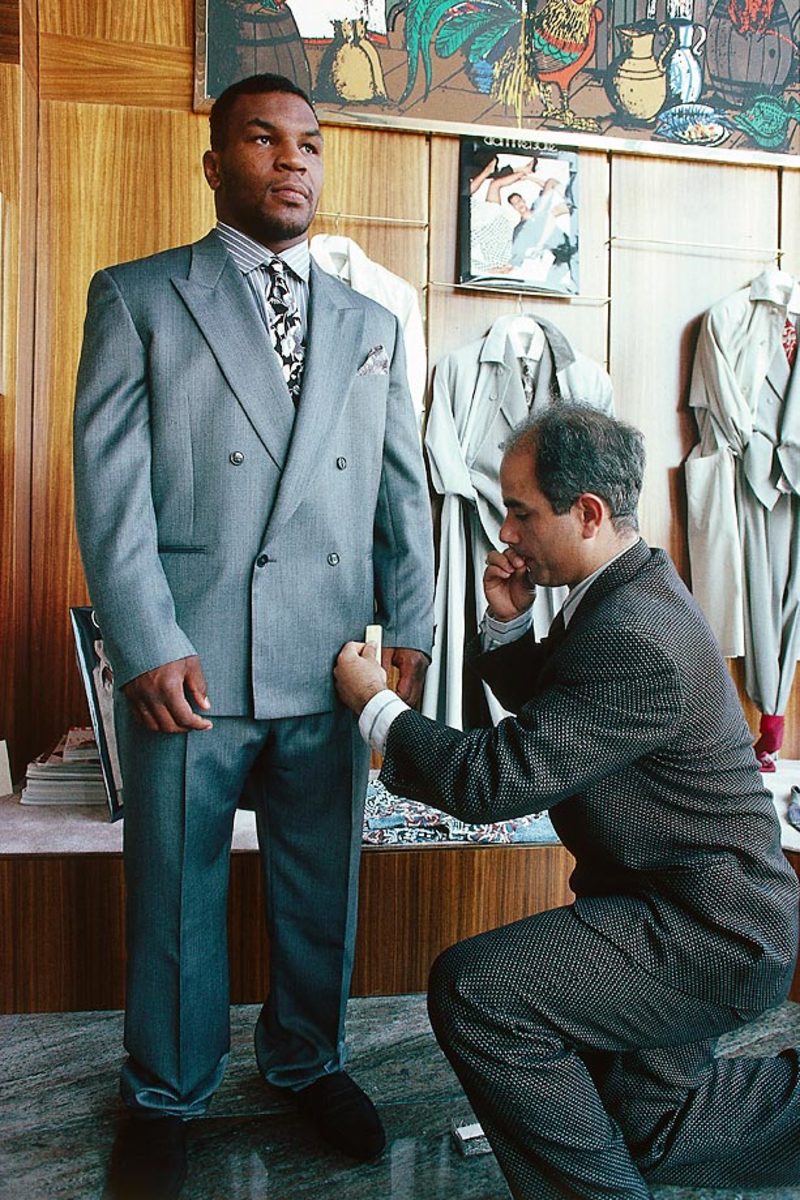

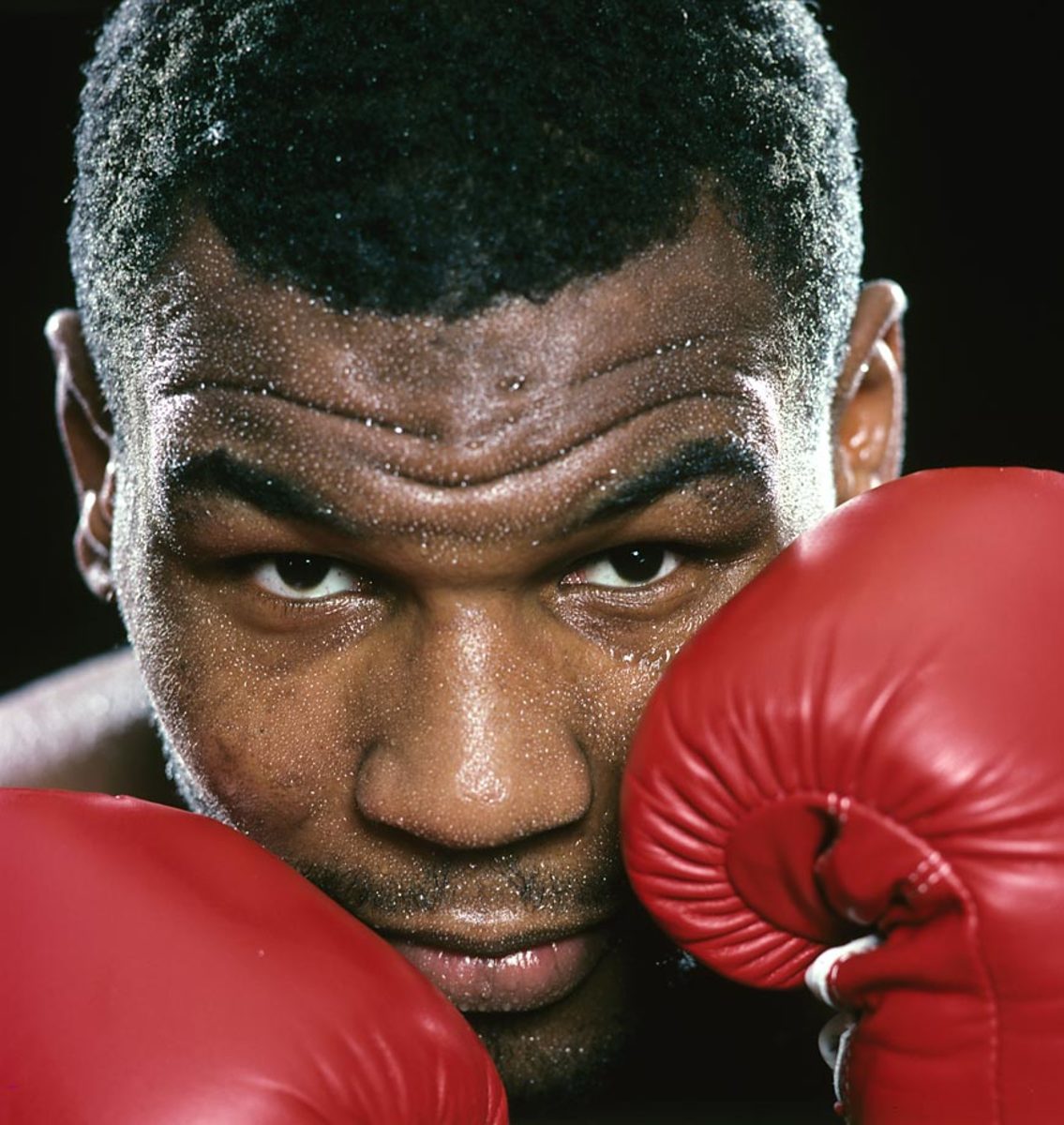

Mike Tyson, 1987

Larry Holmes, 1982

Muhammad Ali and Billy Crystal, 2006

Eric (Butterbean) Esch, 2013

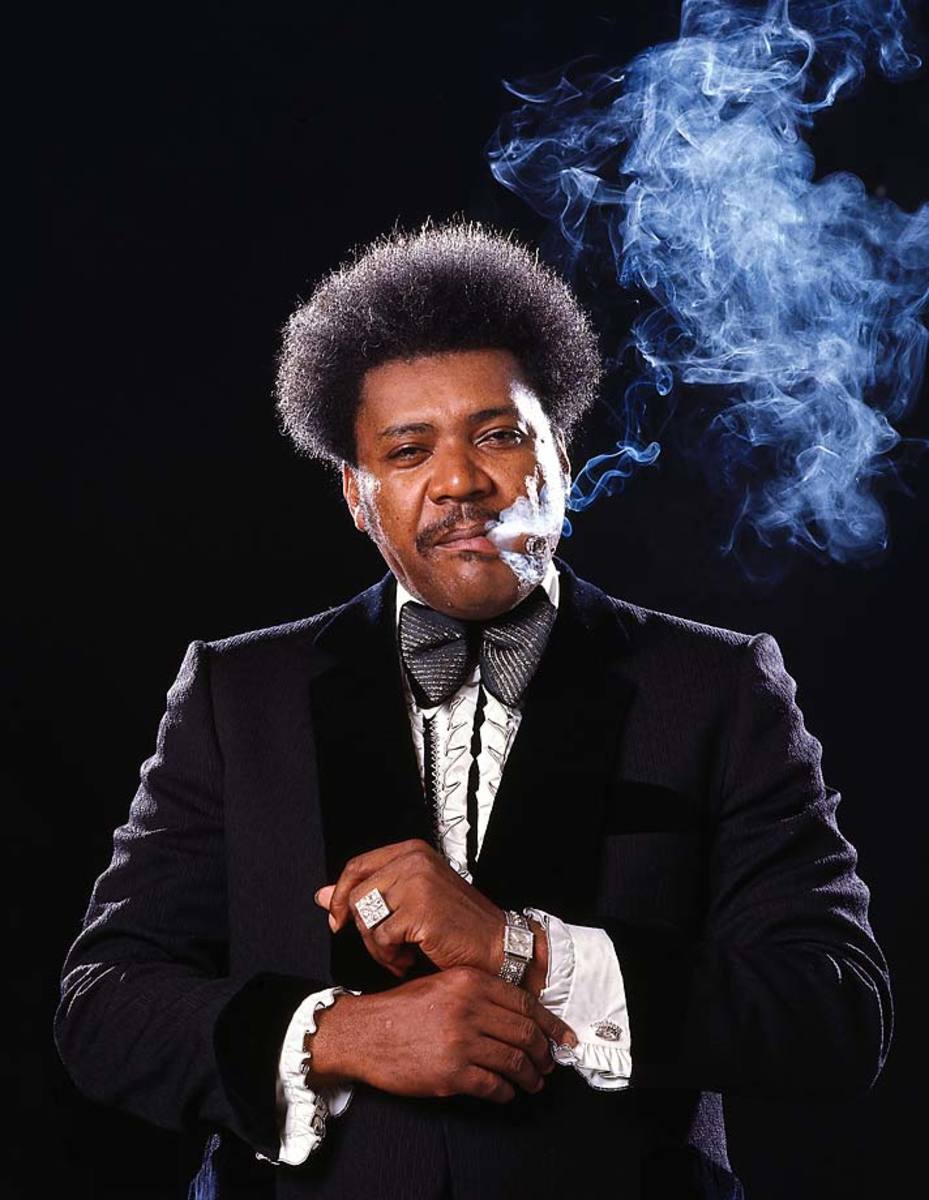

Don King, 1975

Mike Tyson, 1988

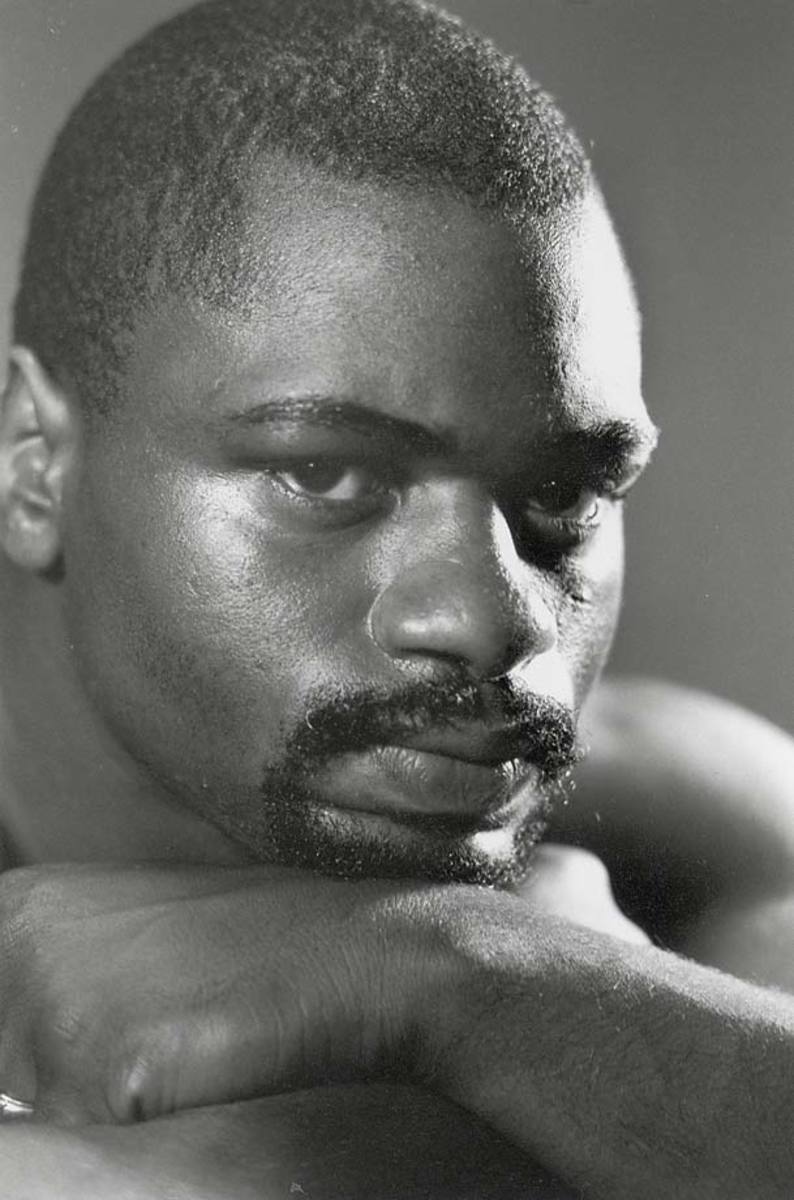

Hurricane Carter, 1963

Arturo Gatti, 2004

Mike Tyson, 1988

Oscar De La Hoya, 2000